Feline Leukemia In Your Cat – FeLV+, FLV+ What To Know – What To Do

Ron Hines DVM PhD

About Your Cat’s Feline Leukemia/Feline AIDS Test

About Your Cat’s Feline Leukemia/Feline AIDS Test

Feline Immunodeficiency Virus FIV

Feline Immunodeficiency Virus FIV

Which Vaccines For My Cat & When?

Which Vaccines For My Cat & When?

Feline leukemia (FeLV) is a common life-threatening disease of young and middle-aged cats. It is caused by a retrovirus. The virus spreads from cat to cat through prolonged close contact or bites from infected cats. It can also be passed from a FeLV-positive mother cat to its kittens. This virus and its distance cousin, feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV), have the ability to cause a slow, generalized decline in your cat’s health. Of the two, FeLV is the worst. Twenty-five or thirty years ago, FeLV was considerably more common than it is today. That is because the vaccines your veterinarian has today are better than they were then, and because veterinarians now can offer you rapid, in-office tests to detect the virus’ presence earlier. (read here)

How Common Is Feline Leukemia?

That is a difficult question to answer. It depends on you and your cat’s lifestyle. If your cat is allowed to roam, if it did or did not receive vaccinations against feline leukemia when it was young, as well as the geographic area where you and your cat live all come into play. Cornell Veterinary School suggests that 2-3% of all cats in the United States probably carry the FeLV virus. However, when cats were presented to them because of signs of illness, the number of FeLV+ cats jumped up to 30%. A similar sharp upward trend occurs when the cats sampled reside in animal shelters. A Florida sampling set the percentage at 2.3% – with your cat’s age, sex, health status, lifestyle, and source being the major determining factors. Adult cats are more likely to be seropositive for FeLV, sexually intact adult males are considerably more likely to be positive and outdoor cats that are sick at the time of testing much more likely to be positive for FeLV than healthy indoor cats. (read here) In the UK, the estimate is 1-2% of the Nation’s cat population. But again, that is highly dependent on which groups of cats are being sampled. In locations where few cats are vaccinated against FeLV, the disease is more common. There are reports that over 11% of cats tested in Northwestern China carry the virus – and almost 25% in Thailand. However, depending on the tests used, those numbers could be inflated by non-pathogenic (endogenous) FeLV virus (a replication-defective provirus) that pose no health threat to your cat. I will tell you more about feline leukemia proviruses later. In 2023, a group of UK, Spanish, and Italian veterinarians published a study showing that a positive in-office Snap Text was no guarantee that your cat actually harbored pathogenic (dangerous) feline leukemia virus. Among 18 cats, false positive FeLV in office tests appeared most likely to yield false-positive results when the cats were already anemic from causes other than FeLV. When those other causes were addressed, the cats returned to negative status. How anemia caused the false test results remains unknown. They suggest that all in office FeLV tests be confirmed at a central veterinary laboratory. (read here)

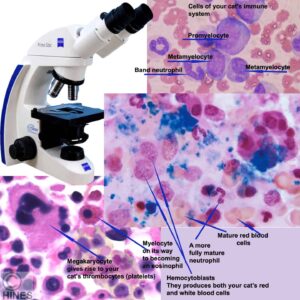

Feline leukemia is not a very descriptive name for this disease. Less than half of the cats infected with the FeLV virus ever develop leukemia. When and if they do, it is not actually the FeLV virus that was the cause. It occurs because your cat’s own cancer-preventing mechanisms have been crippled by the virus’ ability to produce immunosuppression – similar to the effects the AIDS virus has on humans. That immunosuppression and lack of immune cell cancer hunting “policemen” most often results in lymphomas, not leukemias. (read here) That same bone marrow suppression is also why so many FeLV-positive cats become anemic. (read here)

If My Cat Is Feline Leukemia Positive, What Will Happen?

The majority of cats that are exposed to the Feline Leukemia virus conquer it and recover. Their bodies mount an immune attack against the virus, producing antibodies that cure them or keep the virus at bay (in check) for the rest of their lives. Veterinarians used to believe that within those cats, the virus was completely eliminated. We now know that that is not always the case. In some cats, the virus continues to lurk in unknown locations – but in a dormant form. Those are called regressive FeLV cases.

When your cat is exposed to the FeLV virus, it can react in several ways. Some cats do not become infected due to the dose of virus being too small or due to their vibrant immune system. Certain genes that some cats inherit seem to favor FeLV resistance. Stress at the time of exposure can also give the FeLV virus the upper hand. Other cats develop a latent infection, meaning that their bodies cannot fully destroy every last FeLV virus, but it can keep the number of virus low so that no illness results (regressive infections). Finally, there are those cats who remain continuously infected and unable to develop an adequate immune response. Those cats are likely to develop associated diseases within a few years. Sadly, most of the cats that become permanently infected with this progressive form of feline leukemia will die within 3–4 years of their diagnosis. Younger cats are particularly vulnerable. I will tell you about these various forms of feline leukemia later.

The destiny of FeLV carrier cats that show no disease (regressive infections) is not preordained. For instance, certain medications such as corticosteroids that suppress natural immunity have been blamed for reactivation of their disease. Environmental stress-related reactivation of the virus has also been proposed. ( read abstracts here & here, or ask me for Westman2019 & Hartmann2020)

Is There More Than One Type Of Feline Leukemia Virus?

Yes.

Exogenous feline leukemia virus = FeLV

Exogenous feline leukemia virus = FeLV

As far as the “wild” feline leukemia viruses your cat might be exposed to, veterinarians believe that they are all quite similar throughout the world. None of the strains of this virus have been reported as being resistant to the vaccines veterinarians give to your cat to protect it. However, like all virus, there are probably strains or subtypes of the leukemia virus that are more pathogenic than others. Veterinarians really do not know. We call all of these “exogenous” feline leukemia viruses, or just FeLV. The most common subtype is FeLV-A. FeLV-A is the variant that some say is most often associated with immune system suppression that results in increased susceptibility to secondary infections of all types. Some suggest that Subtype B is the one most associated with tumor formation. All that is still uncertain.

Endogenous feline leukemia virus = enFeLV

Endogenous feline leukemia virus = enFeLV

Sometime in the ancient past, long before cats were domesticated, wild felines, or their almost-cat progenitors, were exposed to the feline leukemia virus. In those that recovered, portions of the feline leukemia’s genetic material (its RNA) found their way into the cat’s own DNA instructions that passed down through untold generations to the house cats of today. These inherited footprints of past virus exposures are present in all of us. (read here) Although these fragments of virus code might occasionally confuse veterinary PCR test results, these endogenous or provirus particles are thought to be incapable of becoming infectious or causing disease in your cat. (read here)

FeLV/enFeLV Recombinants = FeLV-B

FeLV/enFeLV Recombinants = FeLV-B

Unfortunately, it appears that the common non-pathogenic endogenous feline leukemia virus I just mentioned that passes from cat to cat through the generation appear to be able to combine with the exogenous (“wild”) feline leukemia virus to form a third type of virus in a cat’s body. Exactly what the presence of this form of the feline leukemia virus means to your cat’s future health is uncertain. Some believe that the presence of FeLV-B makes the later development of lymphoma cancer more likely. (read here) That same article emphasized that the presence of other common “sleeping” (=inactive) virus in your cat (feline foamy virus, feline herpes virus, and feline coronavirus) might influence how your cat reacts to a feline leukemia virus exposure. This is all hypothetical – never proven and perhaps incapable of ever being proven.

FeLV/subgroup C = FeLV-C

FeLV/subgroup C = FeLV-C

This particular feline leukemia variant is thought by some to be the one most likely one to produce aplastic anemia in your cat. (read here)

Where Did My Cat Catch The Feline Leukemia Virus?

If the virus did not pass from mother to offspring, your cat contracted the virus from close contact to another infected virus shedding cat. That generally requires mouth-to-mouth contact with the saliva of an infected cat. That can be affectionate grooming, or cat-on-cat aggression. The longer the two cats were together, the more likely that such an event occurs. Veterinarians theorize that affectionate grooming (allogrooming) greatly assists the leukemia virus in transferring from one cat to another. Cat fights and bite wounds are probably a less common mode of virus transfer. But they are another good reason not to allow your cat to roam. The third confirmed virus transfer method, which I already mentioned, is from a mother cat to her kittens. More of those transfers are thought to be after the kittens are born than while the kittens are still in her womb. As cats age, they tend to acquire a natural resistance to the feline leukemia virus – or at least to the diseases sometimes associated with it. However, resistance is never absolute.

Could My Cat Have Caught The Leukemia Virus In A Virus-contaminated Environment, Such As An Animal Shelter?

That is very unlikely. Well run shelters do not lump groups of cats together. The feline leukemia virus only survives for a few hours at room temperature outside of a cat’s body. (read here) Ordinary household disinfectants including bleach as well as detergents, heat and drying, quickly kill the feline leukemia virus on household and cattery and utensil surfaces. The FeLV virus is so fragile that it does not survive long outside a cat’s body – less than a few hours under normal household or cattery conditions. (read here)

If My Cat Is Still Test-Negative For Feline Leukemia, What Should I Do To Protect It?

Nothing is as important as keeping your cat indoors and only allowing it outdoors under your close supervision – most preferably on a leash. The next most important thing you can do is to have your cat vaccinated with a feline leukemia vaccine series when it is young. I do not know of any studies that confirm the actual effectiveness of these vaccines in real life situations, but they do pass the tenants of immunology. I, personally, prefer Boehringer Ingelheim/Merial’s PUREVAX® Recombinant canarypox-vectored FeLV vaccine because it contains no adjuvants, and only the portions of the feline leukemia virus thought to be necessary to develop immunity. (read here) Before a cat receives that or another brand of FeLV vaccine, I suggest that it be tested to be certain it does not already harbor the active FeLV virus. As far as we know, those vaccines should not harm a FeLV+ cat that receives them. But, again, as far as we know, giving these vaccines is unlikely to help cats that already harbor the leukemia virus. Doing so will also give cat owners a false sense of security that their cat is protected.

You might think that your FeLV- negative cat will never go outside, and because of that, the vaccine is unnecessary. But life and the future are unpredictable for all of us. When possible, I administer the FeLV vaccine at 12 weeks of age and a second shot 3–4 weeks later. For young cats, I suggest a third shot a year later and never again.

We all have different risk tolerances and mind sets. No vaccines are foolproof. So if your cat leads a high-risk life, or went missing for an extended time, or got into a cat fight, and you are a worrier, a negative point-of-care feline leukemia test a month after the incident occurred might reassure you. However, it may take much longer than 30 days for a cat to become test-positive. Some believe that these vaccines do not prevent infection; that they simply prevent the development of FeLV-related disease. It is wise for you to request that all vaccines given to your cat be administered low on a rear leg or in the tail to minimize the dangers of inoperable fibrosarcoma formation. (read here)

What Are The Signs Of Feline Leukemia?

Because the effects of this virus are so unpredictable and pervasive, FeLV will be on your veterinarian’s diagnostic list of possibilities for a large percentage of cats that arrive at their hospitals with chronic, but uncertain causes of health decline. Almost any organ or organs in your cat’s body can be affected – its blood, its skin, its digestive tract, its eyes, its mouth. When those cats arrive, an in-hospital (“point of care”) FeLV/FIV test is usually in order. That is particularly true when your cat did not respond as expected to prior treatments for what was thought to be a minor issue, or relapsed soon after treatment was discontinued. Unexplained weight loss is another common sign.

Abortive FeLV Infections

The immune systems of some fortunate cats that are exposed to the FeLV virus appear to recognize the virus as a threat and completely eliminate it from their bodies. We do not know if that is due to genetic characteristics of the particular virus that your cat met, the genetic characteristics of your cat, or both, or due to other factor(s) still to be discovered. When tests are at first positive for FeLV and later negative, we call those cases abortive FeLV infections. Perhaps those sorts of infections are the ones that left remnant, inactive echos of the FeLV virus within your cat’s RNA, the enFeLV I mentioned earlier.

Regressive FeLV Infections

I am uncertain what the difference is between abortive and regressive FeLV infections. I was not the one that invented these classifications, it was pedantic veterinary scholars who did that. I suggest that you just interpret them as a mater of degree, since classifications never have crisp borders. But in some cats, the exposure to FeLV virus causes the cat’s immune system to produce antibodies and/or other factors that eliminate the virus from its bloodstream, but allow the virus to persist in your cat’s body in a hidden, inactive form. These are called regressive FeLV infections. Some estimate that approximately 10% of FeLV cases follow this rout. I believe that considerably more than 10% probably do because the vast majority of regressive cases will never visit a veterinarian to be tested at the intervals required to detect them. That is because those cats look and feel just fine. Regressively infected cats are not thought to be able to transmit FeLV to other cats. However, some believe that regression is not absolute. That is, there is always a possibility that unknown factors might reactivate the virus at some later date. Veterinarians really don’t know. We still have a lot to discover.

Progressive FeLV Infections

These are the classical cases that all cat owners and veterinarians dread. Cats with progressive FeLV infections have persistently high levels of FeLV virus in their blood stream and saliva. These are the cats whose health eventually begins to decline. They are also the cats most likely to spread the virus to other cats. Because this is a progressive disease, symptoms tend to come on gradually. As I mentioned, weight loss is a common first symptom. That might be accompanied or followed by a slight fever. Cats normally run somewhat hotter at your veterinarian’s office, so don’t panic. So, a rectal temperature a bit over 101.5-102.5 F / 38.6-39 C might just be a sign of anxiety. Check your cat’s rectal temperature while it is relaxing at home to verify a true fever – if your cat will not get too upset about that. Cats that are feeling under the weather from a variety of health issues often have their third eyelids extended farther over their eyes than normal. I am always on the lookout for that. But even simple dehydration can have that effect. Lethargy and apathy are other common early symptoms. Of course, just about any health issue could be responsible. It is also common for these cats to assume an unkempt, disheveled appearance due to their lack of interest in grooming – the “sad cat” syndrome.

The Feline Leukemia Virus Does Its Damage In Your Cat’s Bone Marrow

Because the FeLV virus has an affinity for your cat’s bone marrow, where its white blood cells and red blood cells are produced, it is common for infected cats to have abnormal bloodwork cellular results. (and here) When your cat’s specific WBC numbers are low (particularly its neutrophils) your cat is likely to lose some of its ability to fight infections. That could result in skin infections, ear infections, sinus infections and/or mouth infections (gingivitis, stomatitis, etc.). Reactivation of quiescent (dormant) cat health issues, such as toxoplasmosis, or herpes-1 is also possible. (read here) The laboratory reports from FeLV+ cats can also mimic the effects of another virus disease of cats which is now rare in the developed world, due to effective vaccines, panleukopenia. The panleukopenia virus also destroys a cat’s bone marrow. Some suspect that either the immunosuppression that accompanies FeLV, or virus interactions might reactivate or alter the outcomes of other asymptomatic virus lurking in your cat. Virus such as feline foamy virus, feline herpesvirus 1 and feline coronavirus. (read here)

Persistent diarrhea and loss of litter box training occasionally occurs in FeLV+ cats due to the same bone marrow suppression. Your cat’s white blood cells and a healthy immune system are required to confine unwanted bacteria of all sorts to the interior of your cat’s intestines and not allow them access to the deeper layers of its intestinal wall or the body itself. (read here) Although the FeLV virus can be one source of intestinal issues, more commonly these cases turn out to be cases of inflammatory bowel disease, triad disease or a low-grade intestinal lymphoma.

Persistent anemia is also common in progressive FeLV infections. Anemia can be the underlying cause of lethargy, weakness and an unstable gait. When your cat is seriously anemic, its respiration and heart rate is usually elevated as well. Anemia is also apparent in the paler color of its gums. Your vet can confirm anemia through the findings of a low PVC, Hct, or in some cases, low hemoglobin level. Most of these FeLV anemias are of the non-regenerative type, where your cat’s bone marrow has lost its power to produce new red blood cells. Your cat’s bone marrow must be constantly at work producing new replacement red blood cells. Once released into your cat’s blood stream, feline red blood cells have a lifespan of only about 70 to 80 days. Your veterinarian can confirm a non-regenerative anemia by discovering a lack of reticulocytes in your anemic cat’s blood panel results.

When the FeLV virus damages your cat’s immune system, your cat also becomes more susceptible to tumors. For reasons unknown, it is your cat’s lymphocytes that are the most susceptible to lymphoma (lymphosarcoma) cancer induced by FeLV. (read here) There was a time when veterinarians believed that the FeLV virus was responsible for most cases of lymphoma in cats. Perhaps because of the widespread use of feline leukemia vaccines, that is no longer the case. (read here) Some cats that have developed lymphoma have enlarged superficial lymph nodes that can be felt under their skin, some do not.

Reproductive failure

In some FeLV-positive intact female cats, miscarriage, the birth of “fading” kittens or sterility are other common events.

Neurological symptoms

On rare occasion, cats that are FeLV+ develop neurological problems. Those can include personality changes, seizures, and paralysis. We do not know if that is a direct result of the FeLV virus, or if the presence of the FeLV virus allows other “sleeping” (inactive) virus already present in your cat, such as feline herpes-1 (cat flu) to reactivate. (read here)

Is There Hope?

Despite all that I have written so far, some progressively infected leukemia virus cats will remain healthy for many years before FeLV-related diseases eventually claim them. We do not know why, nor do we have methods to predict any cat’s future. Perhaps it is the age at which your cat was first exposed to the virus, perhaps your cat’s unique genetics comes into play, perhaps it is the characteristics of the particular strain of FeLV in its system, or perhaps all three. As I mentioned, miraculously, a few FeLV+ cats never become ill. A recent study associate that with the level of p27 antigen in their blood. (read here)

Lymphoma

I mentioned lymphoma earlier. I mentioned that it is a cancer of your cat’s lymphocytes, and that it is sometimes the result of feline leukemia virus immune suppression. Lymphocytes’ normal activity is involved with the production of antibodies. When cancerous lymphocytes form in aggregates as a solid mass, it becomes a lymphoma. When the individual cancerous lymphocytes float free in the blood, it is referred to as leukemia. Depending on where lymphomas form, the symptoms they produce differ greatly. The symptoms are caused by the crowding out of normal organ tissue by these large, cancerous lymphocyte masses. However, lymphomas that cannot be associated with the feline leukemia virus are much more common than those that can. Those, non-FeLV associated lymphoma tumors are the most common of all tumors that occur in older cats. The most common location for lymphoma tumors to form in FeLV+ or FIV+ cats is in the pet’s chest, within a mediastinal lymph node, where they obstruct breathing and circulation. However, lymphomas can form anywhere that lymph nodes or lymphoid clusters are naturally present in the body. That is why the signs and symptoms of lymphoma vary greatly.

How Will My Veterinarian Decide If My Cat Has Feline Leukemia?

That will be done through blood tests that search for a specific FeLV virus core antigen protein called FeLV-p27. Most of those in-office test kits also detect the presence of the FIV virus. The convenient in-office tests that your veterinarian uses today are handy variations of the in-laboratory ELISA test that predated it. That test was based on the presence of the same viral protein. It is still used, along with a more sensitive FeLV PCR test (e.g., Quant RealPCR™ Test), to confirm the virus’s presence when in-office tests are positive. Interpretation of the PCR test can be helpful in determining which path the virus is taking in your cat, its stage of infection, and in detecting positive in-office tests that are only positive because of the presence of non-active FeLV virus or their fragments (provirus). Unlike the situation with prior FIV vaccinations, prior feline leukemia vaccinations are not believed to result in false positives FeLV tests. (ask me for Westman2019.pdf)

I Have Several Cats, What Should I Do Now That I Know That One Of Them Is FeLV Positive?

All your cats need to be tested. Once you know the FeLV status of every cat, you have several choices. You could have the negative cats vaccinated with a booster shot against feline leukemia and then hope for the best. Many of your mature cats might already be resistant to the FeLV virus. I mentioned that age imparts resistance. You could re-home the positive cat(s), or you could re-home the negative cat(s). I mentioned that the FeLV virus does not persist long in your home or cattery environment. So perhaps your house can be divided into two areas – one for each group. Periodic testing of the negative group would still be wise. In shelter situations, there are folks who pool blood samples from several cats to conserve money. Pooled blood samples might detect that the FeLV virus is present in one of the cats in the group, and then go on with more tests to identify the specific cat(s) However, that is a method of desperation – not something any veterinarian would be likely to suggest.

What About Testing My New Kitten For Feline Leukemia?

The Idexx SNAP and the Zoetis Witness FeLV blood tests can be performed on cats of any age. Unlike the antibody detection blood tests for FIV (which some of these test platforms combine) the FeLV portion of the kit tests for the presence of the FeLV virus itself. However, newborn kittens that are actually FeLV+ can still test negative for several weeks to several months after birth. That is because the number of leukemia virus in their blood must reach a substantial level to trigger the positive colorimetric reaction that these tests depend upon. So, some veterinarians suggest testing the kitten’s mother instead (if she is available) and delaying testing of the offspring, unless the mother turns out to be FeLV+. If one kitten from a litter tests positive, in all probability the entire litter will as well. As with shelter adults, another option used in rescue to conserve scant resources is to test a pooled blood sample from the litter. That is an “iffy” (much less desirable) option. A second test of kittens at 4 months of age usually picks up (identifies) FeLV+ kittens that falsely tested negative earlier. Giving those suspect kittens their vaccination at normal ages and intervals is not known to influence the progress of feline leukemia. Some kittens have been known to revert to negative test results with time (revert to regressive status). When doubt persists, immunofluorescent antibody (IFA) and PCR tests are the most accurate in determining your kitten or cat’s true FeLV status. At some point the ELISA, IFA and/or PCR tests should all agree.

What Treatment Can My Veterinarian Offer My FeLV+ Cat?

Antibiotics

The treatments veterinarians can offer your cat are all symptomatic (palliative). That is, they attempt to deal with the effects of the leukemia virus, not to destroy the virus itself. I mentioned that FeLV+ cats are more susceptible to bacterial infections of all kind. So, antibiotics are high on the list of medications dispensed. When it is a FeLV-induced mycoplasma or bartonella relapsing anemia that is being treated, doxycycline is usually the antibiotic of choice for your cat. In other situations, alternating antibiotics or antibiotic pulsing can be helpful. However, with time, all bacteria become resistant to antibiotics. Creating antibiotic-resistant bacteria in your household is never a good idea. (read here)

Nutrition

A more tempting diet prepared at home for your cat and lightly cooked can be very helpful in combating the poor appetite and weight loss of feline leukemia. It will also give your cat considerably more enjoyment than the inferior industrial stuff sold in cans and bags. Feeding raw meat ingredients are never a good idea when dealing with cats that have a depressed immune system. (read here) When better flavor and aroma is no longer sufficient, appetite stimulants such as mirtazapine, cyproheptadine or Elura® might be helpful. Unfortunately, recent feedback from cat owners indicates that Elura® has a very bad taste. (read here) I have tasted it, the cat owners are right.

Medications To Decrease The Likelihood Of Vomiting Or Diarrhea.

Medications such as injectable maropitant (Cerenia®) are often used successfully to control vomiting in cats. Some have used the tablet form “off label” in cats as well. Although maropitant work best when given for short-term health issues, it has been given successfully to cats for more extended periods. (read here & here) But when your cat feels so bad due to FeLV that it cannot hold its food down consistently, I believe that the only loving thing to do for your companion is to have it euthanized. Metronidazole (Flagyl®), tylosin (Tylan®) and diet changes are also sometimes effective in lessening diarrhea. Give probiotics a try as well. Cats do not tolerate oral over-the-counter human anti-diarrheal products well.

Combating Anemia

I mentioned that anemia due to bone marrow suppression is one of the common effects of the FeLV virus. Since the majority of those cats have lost their ability to produce new red blood cells, medications such as darbepoetin that stimulate red blood cell formation (haematopoiesis) are rarely effective. Some suggest blood transfusions. But by the time a transfusion is required, I also believe the much kinder thing to do is to send your cat on to Heaven.

Antivirals

At one time, it was hoped that one or more of the antiviral medications known to reduce the virus burden of human AIDS patients might help FeLV+ cats. In early trials, all of those medications were found to produce much greater side effects in cats than they did in humans. The only one that is still occasionally brought up in conversation is raltegravir. In one laboratory tissue culture experiment, it appeared to prevent the FeLV virus from multiplying. (read here) In a second experiment, the drug was given to seven FeLV+ cats for 9 weeks. Although the cats’ FeLV virus load did decrease during the treatment time, the number of virus in the cats’ blood stream rebounded as soon as the drug was discontinued, and only one of the seven cats appeared to have obtained possible benefits. (read here) Since that 2015 study, there have been no further studies listed in PubMed that might offer an effective antiviral treatment for your cat.

Immune Modulators

There are folks that believe that one can simply “jolt” a failing immune system back into its functional state – like shaking awake up a sleeping person or kicking a washing machine. As tempting as that might sound, I am not one of the people who believe that that is possible. Polyprenyl Immunostimulant is one of those products. Another is staphylococcus protein-A. A third is interferon Omega (IFN-ω). Another one introduced in 2006 was called Lymphocyte T-Cell Immunomodulator (LTCI). Yet another, Virbagen Omega®, a Virbac product marketed in the UK and EU, but never in North America. Several of my clients, did however successfully obtain Virbagen Omega® here in the USA through a trans-shipper of veterinary pharmaceuticals based in the UK. It never cured a cat. If the cat’s lives were lengthened or shortened through taking these products is something we will never know. Great Theriacs have, and will always be available for you to purchase.

Are There Special Treatments For Lymphoma?

I mentioned that Lymphomas occur in feline leukemia negative as well as FeLV positive cats. However, in my experience, they tend to occur at a much younger age in cats that are FeLV+. Lymphomas are composed of cancerous lymphocytes. Corticosteroids temporarily reduce lymphocyte numbers. (read here) So a few cases of FeLV-induced lymphoma temporarily respond positively to corticosteroid medications (shrink). But corticosteroid medications such as prednisolone are unlikely to prolong your cat’s life when it faces this cancer. In one study, the median remission and survival times for two FeLV antigen-positive cats were 27 and 37 days, respectively. (read here) Chemotherapy is also possible. But chemotherapeutic drugs often aggravate the FeLV virus’ bone marrow immunosuppression (=less red and/or white blood cells produced in your cat’s bone marrow). A second issue is that cats have a reputation for not tolerating “chemo” drugs nearly as well as dogs or humans do. Major side effects are common. When your cat reaches the point where chemo is under discussion, I believe that euthanasia is the much kinder choice for your feline friend.

When My Cat Is Feline Leukemia Positive, What Lifestyle Suits It Best?

As I mention many times on my website, cats that are confined to the indoors live considerably longer than cats that are allowed to roam. Keeping your FeLV+ cat indoors also prevents the spread of the virus to other cats in your neighborhood. Since progressive-class FeLV+ cats have lost much of their natural resistance to infectious disease, disease agents found out-of-doors such as those responsible for toxoplasmosis, bartonellosis, leptospirosis, and cryptococcosis might gain the upper hand. FeLV+ cats are probably less likely to survive encounters with those agents, and all of those organisms have the potential to spread from your cat to you. FeLV+ cats are not good candidates for stays at boarding kennels, travel, veterinary hospital inpatient care or group homes either. All of these situations are likely to increase their stress levels.The most important thing you can do for a FLV-positive cat is to minimize the stress in its life and provide it with a peaceful home.

If you are the keeper of many cats, you might search for a human angel who might be willing to give your FeLV+ cat an individual home. People with a heart so expansive are rare – but they do exist. Placing positive cats in herds does not benefit them. If you were randomly placed in a home to live with five or six strangers, what would be the chances of all of you getting along? If anything, the stress of group living is likely to reactivate stable, regressively-infected FeLV cats and speed the demise of the others.

Some folks believe that cats should eat diets that contain raw meat. (read here) I discouraged that earlier – particularly when your cat is a FeLV carrier. Raw meat (particularly ground meat and poultry products) are frequently contaminated with Salmonella. The majority of times that cats and dogs are exposed to salmonella, they show no symptoms at all or, at the most, a short period of diarrhea. After that, they clear their bodies of the bacteria or remain silent carriers. (read here & here) However, your FeLV+ cat is unlikely to have the robust immune system necessary to defend itself from salmonella and other pathogens such as listeria that can be present in uncooked diets. (read here & here) Raw diets are a potential threat to FeLV+ cats and, through them, to you.

FeLV+ cats might benefit from a visit to their veterinarian for a checkup every six months or the visit of a house call vet. Politely avoid sales pitches for unnecessary add on products the clinic sells – they are a sign of the times. What you came for is your cat’s weigh in, your veterinarian’s physical exam, the report update that you provide and, based on that, the possible need for blood and urine analysis or other tests.

Just as importantly, in determining when to visit your veterinarian again, is your purchase of an accurate scale to keep a weekly log of your cat’s weight at home. Human AIDS is also caused by retrovirus. In people, weight loss is one of the best indicators of serious AIDS-related decline. (read here) At the first signs of a downward trend, see if diet changes or the appetite enhancers I mentioned earlier might reverse or stabilize it. A home cooked diet is often the best answer to stretching your cat’s remaining quality time. (read here)

I would forgo future vaccination boosters for my FeLV+ cat. They are of little or no value to adult indoor cats, and vaccinations of FeLV+ cats against FeLV provides no known benefits. (read here) Avoiding vaccinations is particularly important when it comes to vaccines that contain modified live (living) agents (virus/bacteria). Rabies vaccines marketed in the United States are all killed virus products. So, they should pose no threat of causing rabies – even in an FeLV immunosuppressed cat. But it is a false assumption to think that a rabies vaccination would produce effective protective antibodies in an immunosuppressed cat anyway. State and Federal regulators prefer to ignore that. (read here) Regarding government-mandated rabies vaccinations, I am not encouraging you to violate the laws where you reside. I am just reporting what researcher scientists have many times reported.

My Last Cat Died From Feline Leukemia. When Will It Be Safe For Me To Get Another Cat Or Kitten?

Because the leukemia virus does not survive long in the environment, and provided you have no other untested cats, you can accept a new cat or kitten at any time. But before you do, new cats over ~16 weeks needs to be tested for FeLV. In kittens younger than that, I prefer to test their mothers, since some younger kittens that are infected with FeLV will test negative at first and still go positive later. It can take some time for the number of viruses to become great enough to trigger positive in-office FeLV test kit results. But if the mother is positive, you know the kittens risk of being positive too is high.

Don’t rush or get talked into replacing or adding a cat too soon. There will always be people rushing you to do that because there is always an oversupply of homeless cats and rescues are desperate to place them. But you need time to mourn and accept the loss of the pet you loved. People tend not to make wise decisions after tragedies. It takes time to think clearly again. By all means make a donation in your cat’s memory to a fund that places homeless cats, but wait until the time is right for you, not for them, to accept another cat.

Can I Catch The Feline Leukemia Virus?

No

Feline leukemia does not affect humans, and it is not related to the leukemias that affect mankind. The FeLV virus does not infect dogs either, but it has been reported in lions, tigers, and other non-domestic cats.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.

Exogenous feline leukemia virus = FeLV

Exogenous feline leukemia virus = FeLV Endogenous feline leukemia virus = enFeLV

Endogenous feline leukemia virus = enFeLV FeLV/enFeLV Recombinants = FeLV-B

FeLV/enFeLV Recombinants = FeLV-B FeLV/subgroup C = FeLV-C

FeLV/subgroup C = FeLV-C