Why Is My Dog Or Cat Breathing Abnormally Or Panting?

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Explanation Of Abnormal Lab Results

Explanation Of Abnormal Lab Results

How Dog And Cat’s Lab Tests Are Organized

How Dog And Cat’s Lab Tests Are Organized

This Article Has A Close Duplicate

This Article Has A Close Duplicate

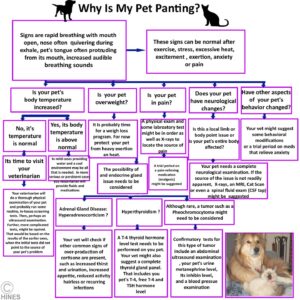

The flow chart image above is how your veterinarian might decide on the cause your pet’s breathing problems.

Term (word) confusion exists in medspeak. But cats and dogs that breath too fast are said to have tachypnea or hyperpnea or to be hyperventilating. In that situation, your pet’s breaths are usually also shallower than they normally are. Pets that take deeper breaths than normal are said to have hyperpnea. Pets that have labored, difficult breathing are said to have dyspnea. Those that breath too slow are sometimes said to have bradypnea (a term that is almost never used). More than one term may apply to the situation your pet is experiencing.

How fast and how deep your dog or cat breathes is controlled by a group of very complex inter-related factors. It is such a complicated process that to this day, it is not fully understood. However, physiologists do know that two control centers exist in your pet’s brain stem (medulla), one for inspiration and one for expiration. More regulation occurs in the pet’s spinal cord and two (the carotid and aortic bodies) sense oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the pet’s blood stream. When all is well, all of them work together to keep your pet’s body well oxygenated and to eliminate waste carbon dioxide through the lungs as it is continually produced (pets with too much carbon dioxide in their bodies are said to be hypercapnic).

Pets in any of those situations that that require increased effort to breathe are said to be dyspneic. Dyspnea is always an emergency. It is one of the scariest situations veterinarians face. These pets are next to the edge, as far as meeting their oxygen need and the least bit of excitement can throw them over the edge, causing them to collapse. They need oxygen – and they need it fast – either by face mask or oxygen chamber.

While the pet is receiving it, your vet will probably ask you many questions: when did this begin? Has it happened in the past? Is there history of recent trauma or electrical cord bites? What about toxic product exposures, allergies, stings, current medications the pet receives, etc.? Has the pet been coughing or sneezing or exhibited any other abnormal behavior?

Often the dog or cat’s physical exam must be done in stages so as not to over stress the animal. Vets keep tracheal tubes at the ready and cut down kits to find collapsed veins, should things take a turn for the worse.

Panting

Dogs and cats that pant are often attempting to lower the temperature of their bodies. In dogs, that can be normal. In cats, it rarely is. Normal reasons for panting include exertion, stress, heat and excitement. Overweight and long-haired pets are more susceptible to the problem. Panting in the absence of those causes is not normal. Abnormal reasons for panting in dogs and cats include fever, anxiety, heatstroke, pain as well as blood, heart and lung disease. Medication overdoses and toxic exposures (~chocolate or insecticide intoxication) need to be ruled out as well. You can see another flow chart on how veterinarians sort out the many possible causes of rapid breathing here:

How Might My Veterinarian Go About Determining Why My Pet is Breathing Abnormally?

Just observing your pet in the exam room is usually sufficient for your veterinarian to recognize cases of dyspnea (exertion on breathing) or hyperpnea (tachypnea or rapid breathing). Both generally mean that your pet is having difficulty meeting its oxygen needs.

Your vet is likely to dispense with small talk and niceties at that point because he or she knows that this is a critical, time-sensitive situation. If the pet is cyanotic or its CRT time is slow, they might rush in some oxygen. In any case, the staff will do their best not to further stress your pet as the examination continues.

My personal choice at this point is to reach for my stethoscope. What a vet hears through that marvelous contraption tells him a lot (heart situations, fluid in the lungs, abnormal lung sounds, decreased audibility etc.). Looking down your pet’s throat for obstructions and lodged items and examining its mouth is quite important. But that must be done gingerly in pets that are on the brink of collapse (extra staff, endotracheal tubes and “cut-down” kits are best brought close at hand when that is attempted).

As your vet proceeds, some things he or she might be looking for are narrow nostrils and nasal passages in brachycephalic breeds (stenotic nares = narrowed nasal passage), crusts and discharges that are evidence of infection in its respiratory system, collapsing windpipes in toy breeds, laryngeal paralysis in larger ones (or other upper airways’ disease), During those exams, tranquilizer injections or body cooling when its temperature is high can help the pet remain calm.

When your vet is satisfied that this problem is not due to obstruction with some foreign object and that the pet is stable enough (a freely open or patent airway) to be restrained for x-rays, that is usually the next step. Radiographs allow your vet to visualize the pet’s heart and lungs – the two most common sites of serious respiratory problems.

Things like an enlarged heart, organs displaced from their proper position, fluid in the lungs or surrounding them, chest tumors, fractured ribs, diaphragmatic hernias or air in the chest might be readily visible on those x-rays or suggested by them. It is also very important to rule those things out to find the real underlying cause of your pet’s respiratory problem.

Veterinarians are quite astute at recognizing the telltale signs of shock in dogs and cats. Shock can account for rapid and/or shallow breathing too. Your pet’s CRT time, body temperature and pulse strength (high BP ref) helps confirm that problem as well. So does a pet’s lack of interest in its environment. “Muddy” colored or brick-red gums, collapse, and, of course, a blood pressure monitor also help confirm the problem. Those pets will need immediate intravenous fluids customized to meet their needs (It is not unusual to have to cut through the skin to place an IV catheter in these critical-situation pets when the veins of pets have collapsed).

Sometimes, x-rays and other imaging techniques like ultrasound help confirm the diagnosis. When they do not, lab work is often required.

But when your pet’s situation is so critical that there is no time for that, your vet might resort to heroic methods – things like exploratory surgery (laparotomy). Lack of oxygen is a situation that demands on-the-spot, bold decisions. Veterinarians always want to be able to tell you that they did all that they could – even when the chances of success were slim.

Specific Reasons Why Your Pet Might Have Elevated Or Labored Respiration:

Anything that inhibits the ability of your pet’s lung to draw in oxygen and expel carbon dioxide will increase your dog or cat’s respiratory rate. Fever, and all the reasons for it that I listed here will do so as well because fever increases oxygen needs.

Exposure to high air temperatures (particularly in humid situations) will increase your pet’s breathing rate and can even result in heatstroke. Excitement, anticipation, apprehension, curiosity will increase your pet’s respiratory rate as well. Uncontrolled pain often increases a pet’s respiratory rate as well.

I cannot list all the situations in which your dog or cat will breathe abnormally, but here are some causes. I have listed them pretty much in the order of frequency that I see them:

Mild to Moderate Heart Failure

In adult and middle-aged dogs in South Texas and Florida where I practice, the most common cause of respiratory distress I see is advanced heartworm disease. But when heart failure with similar signs occurred in older dogs, the most common cause is mitral heart valve disease.

Veterinary cardiologists often ask their clients to monitor the number of breath’s per minute that your dog or cat takes while it is relaxed (resting RRR) or sleeping (SRR). Your pet’s respiratory or breathing rate while it is sleeping (SRR) is usually a bit slower than its resting respiratory rate (RRR). Dogs with rates between 25 and 30 breaths per minute rarely have congestive heart problems (clinical heart disease) as their underlying problem. They may, however have normal RRR and SRR and still have early heart problems (asymptomatic or subclinical heart disease) that are not causing difficulties yet. RRR and SRR can be one of many ways that you judge the effectiveness of the heart medications your veterinarian prescribes (another important one is improvement in your pet’s tolerance of exercise). You can read a 2013 study of respiratory rate as a sign of heart disease here:

Heart problems, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), are another common cause of rapid breathing. Resting breathing rate in cats is quite variable; but normal cats take less than 30–40 breaths per minute.

Chest Trauma – Auto Accidents, Dog And Cat Fights

Most pets that are rushed to me after being hit by a car or mauled in a dog fight are breathing rapidly. Depending on the damage done, they may exhibit the shallow rapid breathing of shock or the labored (dyspneic) breathing common to torn diaphragms, rib fractures, lung bruising (contusions) free blood surrounding the lungs (hemothorax) or air in the chest (pneumothorax). Sometimes blood loss was so great that the underlying cause is the anemia of blood loss.

Occasionally, the shock and circulatory collapse that follows these horrible traumas begins a coagulation cascade leading to intravascular coagulation (DIC).

But also occasionally, when the blow was to the head, respiration will actually be slower than normal due to brain trauma that affected the pet’s brain respiratory control centers.

Shock And Poor Oxygen Perfusion Of Your Pet’s Body

Trauma is by no means the only cause of shock that causes rapid breathing. Sudden allergy events (anaphylaxis), overwhelming infections (septicemia) and electrical shock can all have similar effects.

In all forms of shock, blood pressure and the flow of blood throughout your pet’s body drops to critically low levels (circulatory collapse). In these situations, your pet becomes hypovolemic (not enough volume of plasma [fluid] in its circulatory system). Its body becomes starved for oxygen and its waste carbon dioxide levels build up. Its cells cannot live without oxygen. This carbon dioxide buildup can lead to life-threatening changes in your pet’s body pH (metabolic acidosis). Both need your vet’s immediate attention. Other signs besides abnormal breathing, seen in shock include pale gums, slowed CRT, cool extremities (legs, ears, tail) and a weak pulse.

Acid-Base Disorders

Changes in your pet’s pH balance do not have to occur due to the sudden event of shock. They can build up slowly due to chronic problems occurring in many different organs when the pet’s body can no longer compensate for damage that has occurred.

Your pet relies heavily on its kidneys to maintain a proper acid/base balance – so dogs and cats in terminal kidney failure often share these issues. In end stage kidney failure, pets are usually anemic as well – another cause of rapid respiration (tachypnea).

The ketoacidosis that accompanies uncontrolled diabetes in dogs and cats can also cause rapid respiration. So will the hypoglycemia that occurs when too large an insulin dose is given.

Anemia

Anemia makes it harder for your pet to obtain sufficient oxygen. Consequently, it will breathe faster. The two most common causes of anemia in the tropical regions of the USA where I live are heavy infestation with intestinal hookworms or heavy flea infestations. Hookworm anemia is most common in immature dogs and cats. As they mature, these animals develop an age-related immunity to many parasites that often keeps their numbers in check. (read here) The bone marrow in more mature pets also compensates to produce new red blood cells almost as fast as they are lost to the intestinal bleeding that these parasites cause.

In smaller puppies and kittens, (and even in some mature pets) heavy flea infestations are also a common cause of anemia so severe as to cause the pet’s respiratory rate to be high.

A second type of anemia occurs in more frequently in mature dogs (and occasionally cats). In that form of anemia, pets mistakenly produce antibodies that destroy their own red blood cells. This is phenomenon is called immune mediated anemia or autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Red blood cells are being destroyed in these pets while they are still in circulation. Pets with this problem are often weak and pale. Their bilirubin blood values are high, and they may show bleeding disorders as well due to low thrombocyte counts. Rapid breathing and elevated heart rate are very common symptoms in cases of autoimmune hemolytic anemia.

Feline Infectious Peritonitis – The Chest Form Of The Disease

Feline Infectious Peritonitis which you can read about here is caused by a mutant form of coronavirus. Severe and chronic inflammation that accompanies this disease in your cat can affect the coverings of the lungs and inner chest wall (the pleural surfaces) or the surfaces of abdominal organs and the abdominal lining (visceral and parietal peritoneum). In those situations excess fluid fills those spaces. It can also affect the brain and eyes in its “dry” form and in some cases affect two or even all three locations. When fluid accumulates in the chest, it is common for those unfortunate pets to breathe rapidly (tachypnea) and even pant. When the liquid builds up in the cat’s abdomen, it eventually interferes with the normal movement of the pet’s diaphragm.

The Presence Of Blood Parasites

The two most common ones are the Mycoplasma haemofelis (aka haemobartonella) parasite of cats and Babesia canis of dogs. The first, M. haemofelis is primarily transmitted by fleas, the second B. canis is primarily transmitted by the brown dog tick. Both can cause your pet to become anemic. If that anemia is severe, your pet’s respiratory rate will be elevated. Its heart rate will also increase and, if the anemia is severe enough, a heart murmur may be present as it sometimes is in anemic humans. (read here)

Upper Airway Obstructions And Collapsing Trachea

Some breeds of dogs have been bred to have narrow or distorted airways (nose, nasal passages, pharynx and larynx). Those are the breeds that tend to snore (stertor, stridor). They are called the brachycephalic breeds. When these pets have any sort of inflammation or swelling in those areas (such as in kennel cough, allergies, smoke exposure, etc.) they can have difficulty obtaining enough oxygen. Because their airflow is marginal even in the best situations, they are also the breeds first to suffer from heat stroke and heat exhaustion. In all those situation, they tend to breathe faster and more labored (dyspneic). Similar situations can occur in non-brachycephalic breeds when tumors, polyps, or laryngeal paralysis occur.

A second upper airways’ problem is common in toy breeds (Yorkshire terriers, Poodles, and Pomeranians etc.). It is the presence of a trachea (windpipe) that does not maintain its normal oval shape well because the cartilage rings that help keep its shape are too flabby. Most pets with this problem were born with the tendency, but in a few, cartilage weakened by Cushing’s disease is a contributing factor. In any case, when the problem becomes so serious as to limit your pet’s ability to take in sufficient air, labored breathing (dyspnea) and, occasionally, more rapid breathing will occur. The problem can become so serious as to cause the pet to faint (cyanosis). You can read more about how veterinarians approach this problem here:

Feline Asthma, Feline Bronchitis And Lower Airway Disease

The signs of asthma in cats can be quite similar to the signs of heartworm disease in cats. The signs of asthma in cats can also be easily confused with the occasional outdoor cat infected with cat lungworms (Aelurostrongylus abstrusus). Garden snails spread the parasite.

Some cats, particularly purebreds, develop lung-directed allergies that inflame and narrow the small passages within their lungs (bronchial tree). This results in the narrowing of the airway and causes breathing difficulty (dyspnea), especially when exhaling. These cats often breath with an open mouth. It is common for their chest and tummy to to heave, almost as if they were attempting to pass a hairball. During paroxysms (sudden recurrences) of rapid, shallow breathing you might hear whistling sounds as your cat exhales. These bouts occur from occasionally to frequently. Their severity varies from mild to a life-threatening medical emergency (cyanosis).

Smoke inhalation or bronchopneumonia can cause similar symptoms, although dogs and cats that develop bacterial pneumonia always have some underlying health issue that increased their susceptibility.

Chest Infections – Pyothorax

Some pets develop chest infections and fluid exudate that occupy the space surrounding the lungs (the plural space) rather than the lungs themselves. That is called pyothorax. This problem, like bacterial pneumonia, never occurs out of the blue. There is always an underlying health problem that has decreased your pet’s ability to fight infection. In cats, it might be underlying feline immunodeficiency virus. In dogs, it might be severe malnutrition. In puppies and kittens, failure of the mother to pass on sufficient immunity in her first milk (colostrum). Occasionally, a penetrating thorn, grass seed or sharp object allows the infection to enter, in other cases; it appears to get to the plural space through the blood stream, in other cases, food swallowed the wrong way (aspiration pneumonia) might have been a factor. These pets all have breathing problems, both in rate (increased) and in effort (dyspnea)

Pulmonary Edema/ Anaphylaxis, Vaccine Or Drug Reactions

All of these situations liberate cytokines that cause the small blood vessels throughout your pet’s body to leak fluid (increased vascular permeability). Your pet’s lungs, being very vascular, have the potential to fill with that fluid. It is called edema fluid (pulmonary edema). When fluid leaks under your pet’s skin, it causes puffiness. A similar situation occurs when your pet’s circulatory system is failing and the flow of blood throughout the body is too slow (lymphedema, cardiogenic edema) or when the lymphatic drainage in a specific part of your pet’s body is blocked by a tumor, infection, etc. (a chylous effusion). When all or portions of that fluid are present within the lungs or in the space surrounding them, your pet will have difficulty breathing (respiratory distress). Pulmonary edema commonly occurs in cats with cardiomyopathy. In dogs, I see it most commonly in sudden allergic reactions to things like stings and vaccinations. Some other possible causes are severe infection (sepsis), sudden (acute) pancreatic shock, snake bite, insecticide poisoning, stomach/splenic torsions, parvovirus, very low blood albumen levels (usually due to protein-leaking kidneys), overzealous (too aggressive) IV fluid administration or uremia. For poorly understood reasons, electrical shocks, such as your pet gnawing on an extension cord, can start this process as well (neurogenic edema). In severe situations, your pet’s heartbeat will be rapid, and it’s pulse weak. Sometimes, foamy liquid from the lungs is coughed up as well. These are critical medical emergencies.

Diaphragmatic Hernias

When pets receive a severe blow to their central body, as in a traffic accident, the sudden increased pressure in their abdomens can tear their diaphragms. Generally, they rip where they attach to the chest wall. Without an intact diaphragm, pets have great difficulty breathing. In an effort to compensate, they shift their normal breathing muscle movement from their chest (intercostal muscles) to their abdomen muscles (rectus abdominis, etc.). Their breathing is labored and rapid. Occasionally, pets are born with an incomplete diaphragm that allows the space surrounding the heart to communicate with the abdomen (a pericardial/peritoneal hernia). On even rarer occasion, bloating or other abdominal distress will force its abdominal organs forward through that space and into the pet’s chest limiting the ability of its lungs to expand. When that occurs, the pet suddenly has great difficulty breathing.

Cardiomyopathy In Cats – Hypoxia = insufficient oxygen

Veterinarians do not know why some cats and dogs develop sudden heart muscle damage or cardiomyopathy. There was a time that it was associated with low taurine intake – at least in cats. But pet food manufactures now add that amino acid. Larger purebred dogs appear to be more at risk. It also tends to run in dog lines or families. Purebred cats seem more at risk as well, particularly Maine Coon and Ragdolls. The first signs of cardiomyopathy in pets are often a sudden loss of energy and labored, fast respiration. Read more about this problem in dogs here and in cats here. Should you have a ferret, go here.

Hyperthyroidism In Cats

True hyperthyroidism is quite rare in dogs. I have never seen a case. It has, however, been reported in dogs that were fed large amounts of raw beef neck tissue that included the cow’s thyroid gland. (read here) In older cats hyperthyroidism is quite common. When it occurs, the cat’s metabolism speeds up. Although weight loss and hyperactivity are the most common signs that these cat owners see, these cats often have an increased pulse and respiratory rate and pant as well.

Pulmonary Hypertension

This is a particular form of high blood pressure (hypertension) that affects mainly the blood vessels that run to and from the lungs and within the lungs themselves (the total pulmonary vasculature). Any of a number of problems that impede (block) the flow of blood through the pet’s lungs can cause this condition. One of its signs is shortness of breath during and after exertion. Read more about the problem here.

Aspiration Pneumonia

This is a particular form of pneumonia that occurs when food or liquids accidentally enter the pet’s lungs rather than passing down its esophagus to the stomach. I see it most frequently in infant pets that are being bottle-fed. But it can also occur due to vomiting during anesthesia, coma or due to near drowning. Because the pet’s body has no effective ways to expel this foreign material, cases of aspiration pneumonia can be very difficult to cure – bacteria soon take advantage of the situation. Although coughing is the most common symptom, about half the dogs with aspiration pneumonia show rapid breathing (tachypnea) and fever. Dyspnea is more common in infant pets. Those little creatures cannot elevate their body temperature effectively – so they rarely if ever run a fever in this situation.

Brain Trauma or Inflammation

Occasionally, poor pets are brought to me comatose with head trauma after being hit by cars. They invariably have abnormal respiratory patterns – gasping and periods when they do not breathe at all. These pets have sustained brain stem injury. Brain inflammation or increased pressure within the brain (hydrocephalus) can cause the same symptoms. I have never had a pet showing these signs survive. God’s blessing to pets in this situation is that they feel no pain.

Lung Tumors And Mediastinal Disease

Your pet’s mediastinum is the tissue that divides the two sides of its chest (right from left). It normally contains your pet’s thymus gland, heart, aorta, trachea, esophagus, vagus nerve, and lymph glands. Your pet’s mediastinum is different from the Wikipedia description in an important way; in us humans, this curtain of tissues is complete and isolates each side of the chest. In dogs and cats it is incomplete – so problems occurring one one side often spread to the other.

Anything that makes the mediastinal area swell, decreases the area for the pet’s lungs to expand and make respiration difficult (labored, dyspneic). Anything that occupies space within or between the lobes of the lungs has the same effect. Tumors are the most common space-occupying masses in both locations. Besides respiratory distress, problems in this area generally cause exercise intolerance, excessive panting and coughing.

While pets with upper airways obstructions tend to have difficulty in inhalation, pets with lung or mediastinal disease often have problems during inhalation and exhalation. Those with fluid or edema in the chest and lungs tend to have most difficulty during exhalation (see chart at top of page). Cats hide these signs better than dogs and tend to be brought to veterinarians later – when the situation is more critical. Some cats can be frightened and agitated in this state and may simply keel over and pass away upon sudden exertion or while the vet and tech struggle to examine them.

Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA)

When your puppy or kitten was in the womb, there was no sense in large volumes of blood passing through its lungs because they were filled with fluid and not exposed to the oxygen in the air. At that stage, your pet relied on its umbilical cord and its mother’s placenta to meet its oxygen needs and to discharge carbon dioxide and other wastes.

To bypass the lungs, the embryonic pet had a channel (shunt) between the vessels that led to its lungs and the main blood vessel supplying its body (the aorta). That channel is called the ductus arteriosus. The fetal pet had another hole between the left and right side of its heart that also helped bypass its lungs (the foramen ovale). At birth, both those channels are supposed to close, and usually do during the first day. Occasionally, one, the other or both do not close. That is a patent ductus arteriosus. Its presence prevents the pet from receiving sufficient oxygen. If you are fortunate, your vet picked up its distinctive heart murmur on the pet’s first puppy exam. But many cases are missed. In those cases, dogs are usually presented with difficulty breathing. By that time, the problem is often accompanied by heart damage (enlargement = cardiomegaly).

For unknown reasons, female dogs have twice the number of cases as do males. Dogs more prone to the condition include poodles, bichons, Maltese, Pomeranians, Chihuahuas, collies, spaniels, keeshonds, and Shetland sheepdogs; but any breed can suffer from the problem. The problem produces a distinctive heart murmur. When I was in school, they called it a “machine murmur”. You can hear the sound your vet might hear through a stethoscope here.

Ingestion of Stimulants

Dogs just love to munch on forbidden stuff. I suppose they think we save all the good food for ourselves. Should they get a hold of stimulants, such as amphetamine-type human medication (e.g. Adderall® /Concerta® to treat ADHD), eat substantial amounts of chocolate (chocolate/methylanthines poisoning) or swallow a nicotine-containing transdermal patch their respiratory rate will be rapid (tachypnea). Many insecticides have the same effect.

These are all medical emergencies because they can rapidly deteriorate to seizures and death. Late in these poisoning cases, the pet’s respiratory rate can actually be depressed.

Transfusion Reactions

The rare transfusion of a mismatched blood unit (or one that was incompatible for poorly understood reasons) to a dog or cat can cause rapid respiration (tachypnea) and a rapid heart rate (tachycardia). Most of these reactions are mild to moderate, transient, and can be managed by your veterinarian. (read here)

Rare And Extremely Rare Causes:

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia Syndrome (Immotile Cilia Syndrome)

PCD is usually a genetic problem that occasionally occurs in dogs, people and mice. But something similar can occur in pets that suffer from long-term respiratory infections. We all rely on the wavelike action of tiny cilia (hair-like projections on the surface of cells that line the pet’s respiratory system) to move dust, dirt, pathogens and secretions out of our lungs. In occasional dogs, these cilia fail to function properly. That leads to bronchitis, pneumonia and sinusitis. When the lungs and airways of these pets can no longer function adequately, the pet’s respiration will be negatively affected. They will breathe faster, and their breathing will be more labored. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) has been reported in doberman pinchers, Newfoundlands, bichon frisé, Old English sheepdogs, English springer spaniels, golden retrievers, English pointers, Gordon and English setters, and rottweilers. (read here)

Histoplasmosis And Blastomycosis

Histoplasma and Blastomyces are two fungi that occasionally become established in the lungs of dogs – and, much more rarely, cats. These fungi are quite content to live free in the soil. They both prefer moist conditions, moderated temperatures and rich acidic soils or compost. That is probably why they are often found in soils contaminated with bat or bird droppings.

We and our pets have probably all been exposed to these fungi because they are so common in our environment. In humans, over 95% of the time, our immune systems rapidly overcome the organisms once they have been inhaled. That is probably true in dogs and cats as well. But in pets that are chronically stressed or have weakened immune systems, those fungi can prosper in the lungs. It is also thought that living or visiting highly contaminated areas can sometimes exposes pets to enough fungal spores to override their natural defenses.

In the lungs, these fungi germinate and have the potential to form granulomas, concentric layered masses of dead tissue and inflammatory cells (similar to the aspergillomas one sees in the lungs of birds and dolphins). Once that situation occurs it is difficult to obtain permanent cures because medications penetrate these masses poorly. In those pets, weight loss, weakness, low-grade fever, shortness of breath and dyspnea are common. Not all pets with this problem cough. As the disease progresses, the fungus can migrate to many other areas of the pet’s body. Histoplasmosis also has the ability to enter the body via the intestine. In those cases, lung involvement may be absent. Veterinarians may be alerted to these systemic fungal problems when normal antibiotics fail to cure a suspected case of pneumonia.

Lung Parasites

The most common internal parasites of dogs and cats are hookworms and roundworms. They live in the intestine. But during their journey to adulthood, hookworms and many species of roundworms must pass through the lungs (a liver lung migration). If enough parasite eggs were accidentally eaten by the pet, a condition called verminous pneumonia can develop when all the larval parasites reach the lungs at the same time. The problem is most common in puppies and kittens where lung inflammation caused by the parasites produces coughing and rapid breathing (tachypnea). If blood work is performed on these pets, eosinophilia is common. But fecal flotation for parasite eggs in the stool can still be negative because not enough time has passed for the adult worms to begin producing eggs (still in their “prepatent” period).

A second group of parasites, lungworms, make the pet’s lungs their permanent home. Various ones affect both dogs (Filaroides osleri) and cats (Aelurostrongylus and Capillaria). Cats are exposed to Aelurostrongylus when when they hunt prey that ate snails and slugs. Both dogs and cats become infected when they ingest the stools of infected dogs or cats.

When heavy infections occur, small airways within the lungs become blocked, leading to bronchitis, coughing, shortness of breath, labored breathing (dyspnea) and even dangerous “waterlogged” lungs (emphysema and pulmonary edema). Secondary bacterial pneumonia is common.

Pheochromocytoma Tumors Of The Adrenal Gland

The more common tumors and malfunctions of your pet’s adrenal glands occur in the outer cortical portion of the gland. Those tumors (or those in its pituitary gland that produces ACTH) cause excess amounts of cortisol to be produced (Cushing’s disease). But tumors can also form in the central (medulla) portion of your pet’s adrenal glands. Pheochromocytoma tumors located there in dogs and cats can produce an excess of the stimulatory hormones, epinephrine and norepinephrine, (the catecholamines). When that situation happens, panting, rapid respiration (tachypnea), weakness, nervousness, high blood pressure, collapse and seizures can occur.

Reasons Why Your Cat Or Dog Might Have A Depressed Or Abnormally Slow Respiratory Rate (= Bradypnea):

All the conditions I listed for low body temperature also cause your pet to breathe abnormally slow (bradypnea).

The most common one is the poor tissue oxygen perfusion that occurs in all forms of shock. That can be the shock that accompanies severe infections (septicemia), a major organ failure, acid/base and electrolyte disturbances, anaphylaxis, blood loss, or dehydration. Early in these conditions, respiratory rate is often increased. But as the pet spirals down into circulatory collapse, that situation reverses and respiratory rate slows.

More rarely, hypothyroidism in dogs might cause slower than normal respiration. Head trauma that injures respiratory centers or increases brain pressure can depress respiration rate as well.

All forms of depressant, tranquilization, narcotic and anesthetic medications can slow respiration when given in large doses. So can drugs given for heart rhythm disorders or high blood pressure.

Dogs and cats (like all mammals) experiencing epileptic seizures can have difficulty breathing or stop breathing (apnea) (read here). Brain centers controlling respiration can be affected or the pet’s diaphragm can remain rigid and non-functional – particularly when seizure follows seizure (or in gran mal rigidity).

Organophosphate insecticide poisoning can also cause diaphragmatic paralysis, preventing breathing, (read here) through its effect on the phrenic nerve that supplies the diaphragm. These compounds can even cause long-term damage to normal respiration. (read here)

Dogs also experience a wide variety of sleep disorders that can affect their respiration. (read here)

Complementary tests:

You can see from the length of this article that the list of possible causes of abnormal respiration is huge. I am sure there are many that I neglected to mention at all. So, the number of tests your veterinarian might choose to run would be just as long. You brought your pet to your veterinarian because you were worried that it was breathing abnormally. Your vet was trained to see other less obvious abnormalities that will guide him/her in their choice of tests. Once your veterinarian is sure that your dog or cat is stable, those tests will probably begin with a combination of concentrated observation, gentle hand palpation, stethescopic examination, imaging techniques and some of the many blood tests that I try to explain in DxMe

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.