Ron Hines DVM PhD

See What Normal Blood & Urine Values Are

See What Normal Blood & Urine Values Are

Causes Of Most Abnormal Blood & Urine Tests

Causes Of Most Abnormal Blood & Urine Tests

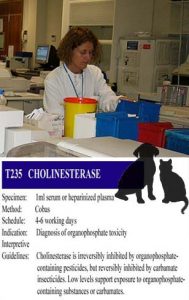

WHAT IS CHOLINESTERASE?

Cholinesterases are very important enzymes in the proper function of your pet’s nervous system. At least one form of these enzymes (acetylcholinesterase), plays an important part in your pet’s ability to transmit chemical impulses (or commands) to muscle cells throughout its body in an orderly manner.

As those impulses jump along between nerve cells (at the synapses), they utilized a chemical called acetylcholine. After a short burst of this chemical, it must be destroyed by cholinesterases. There are two basic types of cholinesterase (or iso-enzymes) in your pet, acetylcholinesterase (aka: AchE, true cholinesterase, RBC cholinesterase) and butyrylcholinesterase (aka: BchE, pseudocholinesterase, plasma cholinesterase). Veterinarians know what acetylcholinesterase does; but it is still a bit unclear what the exact functions of BchE are (Some believe that changes in its level may be related to inflammation).

Some medications and insecticides inhibit cholinesterase (cholinesterase inhibitors = anticholinesterases) causing a cholinesterase deficiency. When that occurs, continuous nerve stimulation causes the pet’s muscles to go into spasm. The result, depending on the severity of exposure and the pet’s susceptibility, progress from salivation and watery eyes, nausea, twitching, stiff gait, agitation, diarrhea, cramping, convulsions, paralysis and inability to breathe (SLUD syndrome). The pet’s eye pupils are often tiny (pinpoint = miosis). Blood pressure often drops and heartbeat slows. The combined effects can be fatal.

Many bug-killing compounds (insecticides) that have this potential (i.e. organophosphates like malathion and carbamates like Sevin™ dust) can enter your pet through its skin, through inhalation or through its digestive tract.

Cholinesterase levels generally return to normal faster when the exposure was to a carbamates rather than to an organophosphate insecticide. Determining your pet’s cholinesterase level can be helpful in confirming over-exposure to these products and ruling out causes that have similar signs (heat exhaustion, hypoglycemia, atypical epilepsy, low blood calcium, digestive disturbances (acute enteritis), allergic reactions (anaphylaxis), snake or black widow bites, etc.).

When low cholinesterase levels, a history of exposure to cholinesterase inhibitor products or typical symptoms make the diagnosis likely, the treatment is quick administration of atropine and pralidoxime (2-PAM, Protopam). Carbamate exposure usually responds to atropine alone.

Why Might My Dog or Cat’s Cholinesterase Level Be Low?

Exposure To Certain Types Of Insecticides

As I mentioned, excessive amounts of two types of insecticides, organophosphates and carbamates, are the most common cause of low blood cholinesterase levels in pets. These insecticides decrease the activity of acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme that breaks down the nerve “messenger chemical” acetylcholine. The signs of organophosphate insecticide exposure tend to last longer, and are often more severe than those due to carbamate exposure.

Cats are particularly sensitive to overdose of organophosphate insecticides. That is why it is so important to never use products of this kind that are intended specifically for dog use, on your cat.

The number of insecticide poisonings in dogs and cats has dropped substantially over the years as the EPA continues to remove them from household and pet use. Today, most are reserved for farm, garden and crop applications.

Things That Can Make A Dangerous Drop in Your Pet’s Cholinesterase Levels More Likely To Occur:

Probably the most common cause is using a product intended for dogs on a cat. Cats are considerably more sensitive to organophosphate insecticides. Many of these insecticides are twice as toxic to cats as they are to dogs. In some cases, the drop in cholinesterase levels due to insecticide poisoning is rapidly lethal to cats, but some cats survive the initial crisis – only to die of fatty liver disease (hepatic lipidosis) later.

The next most common cause for low cholinesterase in pets is using too much of the right product. It can be easy for pet owners to underestimate their pet’s total insecticide exposure. Some owners forgot or did not know that their pet was dipped in the recent past (perhaps at your groomer) and they applied additional flea or tick repellent. Perhaps the home or yard were recently treated with insecticide. Perhaps they combined products, like the older insecticide-laced flea collars with other topical insecticide products. Another common error is not diluting concentrated products correctly.

Another common mistake leading to critically low cholinesterase levels is using insecticide products on pets that are either too young or too sick (debilitated).

Genetics And Idiosyncrasies

Some dogs and cats just appear to inherit a metabolism and cholinesterase activity that is more sensitive to insecticide overdose than other pets. That appears to be why veterinarians and groomers occasionally see a pet react adversely (badly) to a dip or spray that they have used successfully and without incident for many years. Perhaps these chemicals penetrate the skin easier in certain pets. Perhaps some pets are more inclined to lick and swallow chemicals that were meant to stay on the skin. We really do not know.

Lean Dogs And Cats

Insecticides are soluble in fat (lipids). When they are taken up by the pet’s fat, they tend to be released slowly and in more manageable amounts. Thin pets don’t have sufficient fat to buffer the full effects of insecticide overdose. Certain racing dog breeds are known for their leanness (sight hounds). That makes them more susceptible to insecticide overdose than other breeds. The same sort of effect occurs in cats.

Advanced Liver Disease

One of your pet’s two cholinesterases, butyrylcholinesterase (BchE), is made in its liver. In humans, advanced liver disease can cause a deficiency in that cholinesterase but not in acetylcholinesterase. We do not know if the same thing occurs in dogs and cat, but it well may. If so, that situation could account for lower-than-normal total cholinesterase levels and, perhaps, for unexpected insecticide toxicity even when the correct amount was used. (read here)

Medications Used To Treat, Myasthenia Gravis, Glaucoma Or The Mental Decline Of Old Age

There are times when lowering your pet’s cholinesterase levels can be a good thing. One medication designed to do that is neostigmine. It is primarily used to treat a disease called myasthenia gravis that occurs in both dogs and humans. When that disease occurs in dogs, (read here), they often have trouble swallowing and conveying food into their stomach (megaesophagus). This result in vomiting shortly after meals. The problem is rare in pets – but when it does occur, Irish Setters, Great Danes, German Shepherds, as well as Siamese cats lead the list in frequency of occurrence.

Neostigmine helps alleviate the problem by decreasing the pet’s cholinesterase levels. Neostigmine has also been used to treat overdoses or bad reactions to a heartworm medication (ivermectin). However, when too much neostigmine is given, the symptoms produced are the same as insecticide poisoning. (read here) Neostigmine has also been used to treat certain forms of glaucoma. A similar chemical physostigmine, has the same effect.

Drugs with similar effects to neostigmine, rivastigmine (Exelon® patch), which is used to treat human Alzheimer’s disease and a similar drug, donepezil (Aricept®) also inhibit (lower) cholinesterase levels. (read here) If your pet should accidentally eat them, its symptoms might be easily confused with insecticide poisoning. Luckily, the treatment would be the same.

Another drug, Huperzine A, is sold in US health food outlets for “memory support”. In China, it is also used in human Alzheimer’s treatment. Because it is also an anticholinesterases inhibitor, it will lower blood cholesterol levels if your pet accidentally eats it in sufficient amount. (read here)

Your couch potato pet is unlikely to face this issue; but another use of a neostigmine-like medication (physostigmine) is in protective dermal patches for front-line war dogs. (read here) That is because nerve gases, like soman and sarin have the same effects as very powerful organophosphate insecticides. (read here)

Cholinesterase Levels Decline Naturally In Aging Dogs

Studies in humans have shown that cholinesterase levels naturally decline in old age. (read here) The same thing appears to occur in dogs.

So one might expect the cholinesterase levels in older pets to be a bit lower than those in younger pets. The study, referred to above, seemed to show that these older, absent-minded pets might even benefit from the same cholinesterase inhibitors used to treat Alzheimer’s disease in humans when their memory begins to fail (canine cognitive dysfunction = CCD). Both their memory and ability to learn appeared to improve on medications that increased their cholinesterase levels. However, another study did not find an association between low cholinesterase levels and CCD, although it did note that cholinesterase levels were generally lower in elderly dogs. (read here)

Sudden Changes In Your Pet’s Weight?

In the Spanish/Turkish veterinary study I referenced earlier, fat beagle dogs put on a diet, saw their BchE cholinesterase levels go down while their AchE levels went up.

Toxins Liberated In Sudden Bacterial Intestinal Disease (endotoxemia)

The same Spanish/Turkish veterinary group found that BchE cholinesterase decreases in experimental endotoxemia in dogs, In those cases giving choline appeared helpful in moderated that effect.

Are There Situations When My Pet’s Cholinesterase Levels Could Be Elevated?

Hemolysis (destruction of red blood cells) can falsely increase cholinesterase levels in serum/plasma samples by releasing more of these enzymes from destroyed red blood cells.

The Spanish/Turkish veterinary group also looked at BchE cholinesterase levels in diabetic dogs and found them to be higher than normal. (read here)

As I mentioned before, when fat beagle dogs were put on a diet, their acetylcholinesterase (AchE) levels went up while their BchE cholinesterase levels went down.

It is also possible for cholinesterase levels to rebound to more than their normal levels some time after exposure to cholinesterase inhibitor chemicals has occurred. This study was done exposing pigs to nerve gas, but nerve gas and organophosphate insecticides share many of the same characteristics. (read here)

The Limitations Of Our Currently Available Tests

Cholinesterase test results can be quite difficult for your veterinarian to interpret. In dogs and cats that are showing typical signs of insecticide or other cholinesterase-inhibitor poisoning, finding their cholinesterase levels to be 25-35% (or more) below normal confirms the diagnosis. However, finding their cholinesterase levels to be normal does not rule it out. (In 2013, if you live in North America, your pet’s blood sample will probably end up being analyzed for cholinesterase at Cornell Veterinary School’s Diagnostic Laboratories – regardless of where it was initially sent)

No one is entirely satisfied with the diagnostic accuracy of cholinesterase tests that are currently available – that is why so many different methods are currently used to measure cholinesterases.

Complimentary Tests That Come To Mind:

CBC and a blood chemistry panel, Diagnosis of organophosphate poisoning is often made based on the pet’s history and a “rule-out” of other possible causes. So checking your pet’s body temperature for possible heat stroke and its blood glucose level for possible hypoglycemia are advisable. Assays for other possible poisons, including chocolate poisoning might also be considered. Tests to eliminate the possibility of sudden gastroenteritis that might give similar symptoms to insecticide poisoning might be in order as well. Test doses of atropine and/or 2-PAM, the medications that counteract the effects of insecticide poisoning, can be quite helpful in making the diagnosis. When a possible insecticide/organophosphate overdose was fatal to a dog or cat, stomach contents or liver need to go to a diagnostic laboratory for an organophosphate assay. In living pets, this is rarely done because of the substantial cost of the assay and the unreliability of the results.

DxMe

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.