What Is New In Heartworm Prevention, Diagnosis And Treatment?

Ron Hines DVM PhD

More general information on heartworms

More general information on heartworms

Heartworms, The Slow Kill Versus Fast Kill Treatment?

Heartworms, The Slow Kill Versus Fast Kill Treatment?

For some non-heartworm causes of coughing in dogs, go here

For some non-heartworm causes of coughing in dogs, go here

What Is Currently The Most Effective Monthly Heartworm Preventative?

The most effective monthly treatment against heartworms is moxidectin. (read here) Moxidectin, combined with doxycycline antibiotic, is also the most effective second choice option, versus the FDA approved (and preferred) melarsomine treatment, for curing confirmed cases of heartworm disease in your dog. (read here) Moxidectin-based product’s main advantage over ivermectin-based monthly heartworm prevention products is probably that moxidectin persists in your pet’s body longer. (read here) By the end of the month, ivermectin affords less protection.

Moxidectin is an ingredient in Advantage Multi®/aka Advocate® topical flea and heartworm prevention drops. Similar generic products are Parasedge™ and Imox Topical Solution™. Moxidectin is also available in an every-six or every-twelve month injectable form, sold as Proheart 6® and Proheart 12®. I do not utilize those two products for my dog because they are no better in preventing heartworm infections than the monthly topical and oral forms of moxidectin and because reactions to these injectable formulations have been reported. (read here) Moxidectin is also found in Simparica Trio® for Dogs and Bravecto Plus® for cats. (read here) Topical moxidectin is also approved by the FDA to eliminate heartworm microfilaria (larva) that circulate in the bloodstream.

Has My Dog Or Cat’s Risk Of Catching Heartworms Changed In The Last 10 years?

That depends on you and your pet’s lifestyle and what part of North America or the rest of the world that you live in. The major risk factor, other than exposure to the out-of-doors, is the abundance of mosquitoes. That means temperate climates and abundant rain raise your pet’s exposure risk.

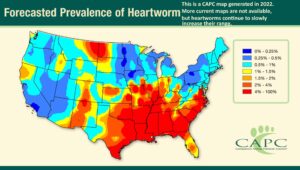

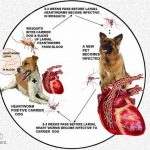

The mosquito bite-transmitted heartworm larva are now present in all 49 states (all but Alaska). (read here) Even though Alaska has plenty of mosquitoes, their summers are said to be currently too short for the parasite microfilaria to develop into their infective stages there. Cases of heartworm disease in dogs in Alaska and other frigid (or arid) locations tend to be in dogs infected elsewhere. In Europe, heartworms have gradually moved northward. In Australia, heartworm cases have recently appeared inland from the Aussie subtropical coast.

In the United States, areas of heavy infection mirror the areas where the 16 common species of mosquitoes that transmit heartworm larva (microfilaria) are found. Those areas used to be those with mild winters, high humidity, lots of rainfall and water impoundments. An unusually cold winter, or a period of drought, was often followed by a temporary decline in the number of heartworm cases that veterinarians saw. But other factors come into play too. Urban areas with high incomes have fewer cases than poorer economic areas – probably due to better mosquito control, as well as a citizenry more likely to give their pets monthly heartworm preventatives. In the last few years, heartworms have extended their North American range into southern Canada. Most attribute that to climate change. (read here) Most parasitologist believe that heartworm larvae do not become infectious in mosquitoes at temperatures below 57 F/14 C. (read here).

Many suggest that it is climate change that is increasing the range of heartworms. But there are those that believe that it is today’s greater pet owner willingness to test their dogs and cats for heartworms and better and more reliable test methods that account for much of the increase in reported cases.

Has My Cat’s Risk of Catching Heartworms Changed Too?

If your cat routinely goes outdoors, whenever the chances of dogs in your area catching heartworms goes up or down, the chances of your cat becoming infected changes accordingly. Parasites, including mosquitoes, periodically mutate and adapt to a new host. So one cannot guarantee that cats will remain a second-best host for heartworms forever. (read here) Mosquitoes also tend to prefer to suck blood from the largest animals available. That might give cats a slight advantage in a mixed cat and dog community.

Studies to determine how common heartworm infections are in cats tend to miss more cases than they do in dogs. That’s because the in-office tests we veterinarians use are ELISA-based. They look for a specific protein that diffuses from the reproductive tract of gravid (“pregnant”) adult female worms. Infected cats rarely have more than 1-3 adult heartworms. If they are all males, or are all still juveniles, the test will be falsely negative.

But even one mature female worm is capable of doing your cat considerable damage. (read here) It’s been estimated that these tests pick up ~89% of infected cats versus 92% of infected dogs. Others are less optimistic about the test’s value in cats, although heat-treating the blood sample before running the test is thought to improve its accuracy. (read here) A recent study of 1000 stray cats in Florida animal shelters found that 4% of them were positive for heartworms. (read here)

I Read About Drug-Resistant Heartworms – How Common Are They?

I mention on my website that there are pockets in the United States where some heartworms have become resistant to monthly ivermectin-based heartworm preventatives such as Heartgard®. (read here) The phenomenon is called MP3 or JYD-34 resistant heartworm strain macrocyclic lactone resistance (ML resistance). What has occurred within these resistant heartworms is not fully understood.

Researchers thought that mutations in a specific heartworm gene (the P-glycoprotein gene) was responsible for that drug resistance. Others now attribute heartworm drug resistance to mutations in the parasite’s β-Tubulin. Whatever the change or changes are in these resistant heartworms, it causes a decrease in effectiveness of most of the monthly heartworm preventative formulas (ivermectin, milbemycin, selamectin and moxidectin).

Of these compounds, several studies have found that moxidectin is currently the superior preventative of the four. (read here, here & here) That may be because moxidectin persists in your pet’s blood stream the longest of the four.

Heartworm resistance is not a nationwide problem yet, and may never become one. In the United States, when drug resistant heartworms are found in dogs – despite their taking their monthly heartworm preventatives, it is usually a pet living in areas where rain is abundant, winters are mild and where the rain that falls eventually drains into the Mississippi River.

Are The Snap Heartworm Tests Always Accurate In Detecting Heartworm Infections?

The Idexx Snap® test, or its competitor, Zoetis’ Witness®, that veterinarians use are quite accurate in detecting if your dog is infected with heartworms – considerably more so than the earlier tests we had (the Difil Test) that just looked for heartworm larva circulating in your pet’s blood.

But no tests as complex as a Snap® or Witness® are free from occasional errors. Certain situations can trick the tests into giving false negative or even false positive results. Both look for tiny protein fragments that mature female heartworms release into your pet’s blood. So dogs with few or no mature female heartworms or only male heartworms can give false-negative results. (read here & here) So, if you live in a high heartworm area and heart and lung issues are seen or suspected in x-ray images or by symptoms or ultrasound, negative heartworm test results need to be confirmed by more sophisticated tests performed at a central laboratory. Heat treatment of your pet’s blood sample prior to testing can also reveal the hidden presence of heartworms. (read here)

What Are My Dog Or My Cat’s Heartworm Treatment Options?

I’ll tell you about treatment options for your dog first:

Soon after your veterinarian discovers that that your dog has a heartworm infection, it should begin monthly heartworm preventatives – if it is not already taking them. That is to rid its blood of heartworm larva (microfilaria). Those microfilaria cannot grow into adult heartworms in your dog. They have to pass through a mosquito first. But those microfilaria, when present in your pet’s blood stream, are inflammatory (=NETosis). (read here) The only brand I am aware of that is FDA-approved for the purpose of ridding your dog of microfilaria is Bayer‘s Advantage Multi®. Heartworm microfilaria are killed by the moxidectin this product contains. Other topical products that contain the same amount of moxidectin should, theoretically, be equally effective in doing that. Some vets prefer an injection of the long-lasting moxidectin, Proheart®. Occasional dogs will have reactions when large numbers of microfilaria suddenly die, no matter which product is used. So, some veterinarians give their patients antihistamines and/or corticosteroids during the microfilaria clearing period.

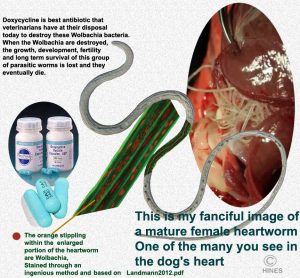

At the same time, most veterinarians will begin your dog on an antibiotic called doxycycline. That antibiotic (or minocycline) is given to destroy a particular bacteria, Wolbachia, that resides within adult heartworms, as well as within the heartworm microfilaria. Wolbachia is what is called a symbiont. The bacteria aids the heartworm in a variety of unknown ways, and the heartworm provides shelter from your dog’s immune system and nutrients for the bacteria to thrive. Neither thrives without the other. Once wolbachia are killed by the doxycycline, there is often a moderate decrease in lung and heart symptoms in the dog – including its cough and labored breathing. Perhaps that is due to shrinkage of the heartworms themselves. Since both doxycycline and moxidectin are generally given simultaneously before attempts are made to destroy the mature parasites with melarsomine, it is hard for me to say which of the two (or both?) drugs are responsible.

Heartworms affect your dog’s entire body. So, it is not unusual for dogs with advanced heartworm disease to have low energy and to tire easily. They are often underweight. A dry cough is common. Many are prematurely gray around the muzzle. Because of heart failure, they often have an oversize belly. Many are anemic. In advanced cases, their liver and kidney tests are often high (serum AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, and urea nitrogen) But none of those results are specific for heartworm disease.

One to two months later, your veterinarian will administer the first dose of melarsomine to your dog. Melarsomine is a very powerful drug. The shot must be given deep within the muscles of your dog’s back. Late in heartworm disease, your pet may not be able to tolerate this medication. So, it is a judgment call how much and when melarsomine and under what circumstances it is administered, based on your veterinarian’s training, instincts and experience. There are no tests your veterinarian can perform that are entirely accurate in determining a dog’s risk. However, the vast majority of dogs do well at the dose and injection intervals suggested on the product’s labels.

A month after the first injection, a second dose is usually given. The product labels still recommend this two-dose schedule. However, the Heartworm Society suggests giving a third dose the day after the second dose is given – followed by strict limitations on your dog’s exercise for at least the following month. Some veterinarians suggest exercise restriction for a considerably longer time. We don’t want a tangled mass of dead or dying heartworms forming a dangerous embolism that blocks blood flow to your dog’s lungs. Administration of aspirin in an attempt to prevent blood clots in dogs undergoing heartworm treatment was once suggested. It is rarely suggested now. Aspirin has the ability to cause multiple stomach and intestinal bleeding in dogs – much more so than in humans.

Some veterinarians incorporate a steroid (prednisone) in their treatment plan to minimize inflammation, particularly if heartworm disease symptoms are advanced.

After Melarsomine Treatment, Will My Dog Be Free Of Heartworms?

Melarsomine Treatment does not guarantee that every heartworm in your dog will be killed. A few living worms might remain. Those could be immature worms that were less susceptible to the medications given. We really do not know. Traditionally, veterinarians told their clients that, perhaps 2-5% of melarsomine treated dogs might still have a few heartworms after treatment. Others believed that it was probably closer to 10%. Some veterinarians suggest a longer gap between the doxycycline/moxidectin treatment and the melarsomine injections in the hopes that these more resistant or younger heartworm stages (3rd & 4th stage larva) will mature enough to be killed. The manufacturers of melarsomine, Boehringer Ingelheim and Zoetis, claim that after a two-dose melarsomine injection treatment, 90% of the heartworms are usually killed. The American Heartworm Society claims that after a three-dose melarsomine treatment, 98% of the worms are usually killed.

It is always wise to check a sample of your dog’s blood for living microfilaria 30 days after your pet finishes its treatment, particularly if your dog was positive for microfilaria before the treatment was begun. I would also suggest an ELISA Snap test for heartworms 9 months after the treatment. Should either be positive, it will be a difficult decision for your veterinarian and you as to whether the treatment needs to be repeated.

Just a word of advice; I believe that It would be exceedingly foolish to begin or attempt any of these treatments without the close supervision of your local veterinarian – much like attempting to do your own maintenance on the 747 airliner you plan to be on, on your next flight. I also cannot speak to the safety of using moxidectin in herding dogs with the MDR1/ ABCB1 mutation. But there is some evidence it might be a bit safer than ivermectin in those susceptible dogs. (read here)

Can Heartworms Be Surgically Removed From My Dog?

Yes.

In heavily infected dogs, masses of heartworms occasionally obstruct blood flow to your dog’s lungs severely enough to be a medical emergency. The problem is called Caval Syndrome. Although heartworms appear to prefer dogs over cats Caval syndrome is more common in heartworm-infected cats than in dogs. That is because of their smaller size, one or two mature female heartworms can dangerously obstruct blood flow to a cat’s lungs.

When caval syndrome is an emergency in dogs, heartworms prevent the opening and closing of their tricuspid heart valve. That can be fatal in a matter of days. Respiration is always labored. Weakness is profound. CRT is lengthened. Occasionally, the problem is accompanied by rust-colored urine. This situation is also called Stage/Class 4 HWD. Some even attempt surgery in Sage 3 HWD.

This procedure begins by shaving and prepping the dog’s right jugular vein. Then surrounding the vein with loose suture loops below and above the point where the vein is to be incised in order to control hemorrhage. Then a long, thin mechanic grasping medical device is threaded down the jugular vein to the upper right chamber of the heart. There, the veterinarian opens and closes the grasping jaws of the device, attempting to “snag” one or more heartworms. After a number of attempts, the device is withdrawn to remove any worms that were captured – hopefully 1 to 5 per pass. That procedure is repeated many times until three consecutive attempts produce no heartworms. Then the jugular vein is repaired. After a period of recovery, the dog will still require the standard heartworm therapy. This is an extremely high-risk surgery, taxing to both the dog and the veterinarian. Deaths during the procedure are not uncommon due to the dog’s tenuous situation. Anesthesia is another challenge. Some dogs cannot tolerate general anesthetics at this point, so attempts are made to perform the surgery using local anesthetics combined with physical restraint. The most likely to succeed are probably interventional veterinary radiologists attached to veterinary colleges or practicing in specialty clinics. (read here)

This surgery can be performed on cats as well. (read here, here & here) But mortality is high during and after this delicate surgery because of a cat’s small size. There are interventional radiology departments at American veterinary colleges and probably around the world who will attempt it. Retrieval devices have gotten smaller and more sophisticated, so perhaps small size has become less of an issue. Let me know if the procedure was performed on your cat and I will let others benefit from your experience.

The Slow Kill Method Of Heartworm Treatment

The knowledge that moxidectin was more efficient in killing heartworms, periodic supply chain problems in obtaining melarsomine (which does not currently exit) and the lack of financial resources of dog rescue groups to pay the high cost of melarsomine, led veterinarians at Colorado State University College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, University of Milano Veterinary Sciences and Università di Parma to begin trials to see if using Advantage Multi® and doxycycline, rather than ivermectin and doxycycline might lower the number of mature and immature heartworms in dogs or perhaps, over a longer period of time, eliminate heartworms entirely. (read here, here, here & here)

To date, neither the Heartworm Society, the manufacturers of melarsomine nor the FDA or the EMA have approved this method and there is no lobbying group I am aware of that is urging them to do so. In one study, ivermectin and doxycycline administered over a 36-week period reduced heartworm numbers by 78%. (read here)

The slow-kill method can quite helpful for dogs too ill to tolerate melarsomine or when financial situations preclude melarsomine use. But it is not an ideal option because the worms remain in your dog’s heart and pulmonary arteries longer. Some are opposed to this second option because they fear that heartworms will become resistant to moxidectin. I do not believe that using the slow kill method will encourage heartworm resistance to monthly heartworm preventatives. The population size of dogs and their wild relatives that do not receive monthly heartworm preventatives makes that unlikely to happen. (read here) Besides, the number of dogs on a slow-kill protocol at any one time is a drop in the bucket compared to all the healthy dogs receiving it monthly. The research required to compare the two methods accurately will most likely never be done because there is no financial incentive in doing so.

Are Heartworms A Risk To My Cat?

As I mentioned, the symptoms of heartworm disease in cats are very different from the symptoms of heartworm disease in dogs. Cats are a dead-end host for heartworms. The mosquito that brought it previously drank blood from a dog. The parasite larva (microfilaria) rarely survive in the blood of cats, so even if a heartworm positive cat is bitten by mosquitoes, those mosquitoes do not drink blood containing microfilaria. Also, cats rarely harbor more than one to three adult heartworms. It takes a mature male and female worm to produce microfilaria. And quite often, adult and pre-adult heartworms rapidly die on their own when they are present in cats.

However, during the time mature and immature heartworms are present or disintegrating, the inflammation they generate along with the narrower blood vessels of a cat’s cardiovascular system compared to dogs give heartworms the potential to do considerably damage – particularly to your cat’s lungs. The term for that damage is sometimes referred to as HARD (heartworm associated respiratory disease). The signs of the presence of heartworms in a cat include, coughing, vomiting and asthma-like episodes. That can progress to a wobbly gait, fainting, seizures, or abdominal enlargement with fluid (ascites). A high blood eosinophil count might also bring heartworms to your veterinarian’s mind. But the most common scenario is an in-and-out cat that appeared normal a day or two before, being found critically ill or dead. Cat owners might attribute the pet’s loss to some form of poisoning. Cats that spend time out of doors are considerably more likely to be infected by heartworms than indoor cats – particularly if you live in an area where heartworm disease is common in dogs. Some suggest that the number of infected cats in any area is about 5-20% of the number of infected dogs in the same area. I do not know if that has, or even could be confirmed.

Should I have My Cat Tested For Heartworms?

The tests veterinarians have at their disposal are not as accurate in detecting heartworms in cats as they are in dogs. It is often suggested that for a cat, two different types of heartworm tests should both be run – one that detects the female heartworm protein itself and another that detects antibodies cats often produce when exposed to heartworms. If your cat has symptoms that your veterinarian suspects might be caused by heartworms, your vet will probably suggest an ultrasound examination to see if any heartworms can be visualized. However, because only one or two heartworms can be quite hard to visualize – yet make a cat quite ill, even an ultrasound exam can easily miss seeing them.

Melarsomine is not approved for use in cats. There is no FDA-approved medication capable of ridding cats of heartworms. The best we veterinarians have to offer you is medications that might control or minimize symptoms and pathology. Prednisolone might be suggested to help control inflammation. Diuretics like furosemide might be dispensed to decrease pooled chest and/or abdominal fluids. Medications to assist failing hearts might be helpful. These are the same medications veterinarians dispense when pet’s hearts fail for other reasons. (read here)

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.