(CHF)

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Subaortic Stenosis In Your Puppy

Subaortic Stenosis In Your Puppy

Pulmonary Hypertension And Right-Side Heart Failure

Pulmonary Hypertension And Right-Side Heart Failure

This is one of several articles that deal with a common heart problem that older dogs often face. It is called Congestive Heart Failure or just CHF. The links above concern other heart issues. Congestive heart failure is most common in toy, small and medium dog breeds. The most common reason that dogs develop CHF is the failure of a particular heart valve, the mitral valve, that routs oxygen-rich blood returning from your dog’s lungs from the top left chamber of its heart (the left atrium) to the lower left chamber of its heart (the left ventricle), from where this oxygen-rich blood supplies the rest of the dog’s body. However, mitral valve problems are only one of many potential causes of CHF. Your pet’s heart is a very complex organ with many elements. Failure or malformation of any one of them can eventually produce heart failure.

Even though failure can occur at multiple heart locations, your dog’s heart has limited ways in which it can respond. It can beat faster. It can increase the amount of blood (stroke volume) propelled with every beat. It can release more of several hormones (natriuretic peptides). The compound released by the upper two chambers of your dog’s heart is ANP. Another. released by the lower two chambers, the ventricles, is BNP. Both peptides decrease your dog’s circulatory system’s blood vessel resistance to the passage of blood. Your veterinarian uses the level of one of these cardiac hormones, BNP, as a marker to detect hart damage. Read about the proBNP test here.

When your dog’s heart can no longer supply its body with sufficient oxygen due to a faulty valve or another cardiac issue, it does not go unnoticed by the other organs in its body. In a complex manner, the dog’s cardiac situation activates the renin-angiotensin system (RAS). The RAS system also attempts to lighten the workload of your dog’s heart. Some blood vessels increase their diameter to allow more blood to pass. Other in less critical areas constrict. The RAS system has dramatic effects on your dog’s kidneys. It allows for more water to be reabsorbed from its urine as it is formed and for less sodium to be excreted. (read here & here)

These many circulatory adjustments are effective in providing your dog’ body with sufficient oxygen for a while. That might be for months or perhaps even for years with the aid of medications dispensed by your veterinarian. But the common canine heart issues are all progressive. Eventually, most dog cannot compensate for their heart’s decreased capability to do its job. That is the point where your dog’s heart will begin to enlarge and alter its shape. It is a gradual process. That is also the point where the symptoms of heart failure, regardless of the underlying cause, become the same or quite similar: a cough, decreased exercise tolerance, fatigue, eventual swelling of the abdomen, pooled chest fluids and difficulty breathing. There are links at the beginning of this article to some of those other underlying heart issues not directly related to your dog’s heart valves: dilated cardiomyopathy, subaortic stenosis, and pulmonary hypertension. But even with those issues, as the dog’s heart enlarges and its heart’s shape changes, its heart valves are bound to distort in their shape and efficiency too. To those mentioned causes of heart failure, consider adding heartworm disease and, in the southern portions of the United States, Chagas Disease.

The most common cause of heart failure in humans like us and the most common cause of heart failure in dogs are quite different. In people, it is damage to the heart muscle itself due to blocked coronary arteries that usually begins the CHF process. For reasons still unknown, dogs and cats are extremely resistant to coronary artery disease – no matter how greasy their diet may be or how obese they become.

How Blood Flows Through Your Dog’s Body

The Electrical System Of Your Dog’s Heart

Animate My Heart’s Electrical System:

Your Dog’s Heart Valves

I mentioned that veterinarians do not know why dogs that consume high fat canine diets do not develop fatty plaques in the arteries of their heart that would lead to heart attacks in the way that occurs in people. Instead, it is the valves directing the flow of blood through their heart that tend to wear out. About three-quarters of heart problems veterinarians see in dogs are due to heart valve problems. Any valve, or multiple valves, can wear out; but the most common one to wear out first is the mitral valve. It is the one that must close before your pet’s left ventricle can force blood throughout the dog’s body. Its job is the hardest of the four valves because the pressure difference across the mitral valve every time your pet’s heart beats is the greatest of all of the four heart valves.

When the mitral valve no longer opens and closes fully, your dog’s heart begins to changes in shape and increase in size. Abnormally high pressure in the wrong locations within the heart causes its walls to become thinner and for the chambers to stretch – much like blowing up a balloon. And as the heart’s shape changes and stretches, the other three valves can no longer close properly either. In dogs that have been diagnosed with a mitral valve problem (mitral insufficiency), veterinary cardiologists often find that the tricuspid valve between the right atrium and right ventricle is also dysfunctional – not able to opening or closing completely.

Mitral valve, or mixed valve, problems have been assigned many different names over the years. Some call it “acquired mitral regurgitation”, others “mitral insufficiency”, “mitral valve prolapse”, “mitral/tricuspid valve regurgitation”, “leaky valve disease”, “chronic valvular fibrosis”, “endocardiosis” or “mucoid valvular degeneration”. They all describe different aspects of the same problem. In these dogs, the two flexible portions (cusps) of the mitral valve have become stubby, thickened or lumpy (nodular). So, like a leaky faucet, they no longer close satisfactorily. When that happens, something akin to backfire occurs (the valve “regurgitates”) and blood flows in the wrong direction.

Heart valves and their thready nest of attachments, the chordae tendineae, are an excellent place for bacteria to become lodged – particularly so if the valve is already somewhat misshapen. Many suspect that dogs with severe periodontal dental disease, a very common source of infection (read here), have mitral valve murmurs and heart valve problems more frequently than dogs that that are free from mouth and tooth issues. Dentists have noticed the same thing. (read here) Dog studies confirm it. (read here) I have seen heart murmurs disappear in my client’s dogs after a course of antibiotics.

In many cases, heart valve problems result in heart murmurs. Your veterinarian should detect heart murmurs during a routine wellness examination. However, not all heart murmurs lead to congestive heart failure. When your veterinarian informs you that he or she has detected a heart murmur, other tests need to be run to determine if the murmur is something you should be concerned about. Anemia, heart developmental defects, infections (with endocarditis), fever and pregnancy have all be known to cause heart murmurs. If nothing major is found to be wrong, they are called innocent heart murmurs. Echocardiography is the best way to determine the seriousness of heart murmurs.

Some believe that the majority of dogs 8-10+ years of age already have heart valve defects to some degrees. The “wear and tear of time” is part of normal aging. At first, those valvular leaks are minor and produces no more than a high-pitched murmur with no resulting health problems. When it is the mitral valve, it is usually most audible on the left side of your dog’s chest, just behind its elbow.

There are some dog breeds, such as Cavalier KC Spaniels, that appear to have an increased susceptibility to heart valve disease, That is thought to be due to inherited genetic defects. (read here)

More About What Happens When Hearts Fail

Volume And Pressure Overload

As I mentioned, when the powerful left ventricle contracts to force blood throughout your dog’s body, but its mitral valve cannot stand up to the pressure, blood leaks back into the left atrium (regurgitation). When that happens, the freshly oxygenated blood coming from your dog’s lungs has nowhere to go. The left ventricle, where the blood was headed, is already too full of blood that should have moved from there into the pet’s general circulation through its aorta. Pressure then increases back into the lungs (= increased pulmonary pressure aka pulmonary hypertension). The lungs expand with this pooling blood and some of that blood serum leaks out through the lung’s small blood capillaries and into the small spaces (the alveoli) normally filled with air (= cardiogenic pulmonary edema). This doesn’t happen independently. As the heart valve deteriorates, the heart also enlarges as it tries to keep up with its increasing workload. The enlarged (hypertrophied) heart begins to press on your dog’s windpipe. That, plus the excess fluid in its lungs, is the cause of its cough.

The right side of your dog’s heart deals with blood returning from its body to be oxygenated again. With time, the increased lung pressure due to pulmonary edema and the enlarging weakened heart cause the tricuspid valve that separates the right upper chamber (the right atrium) from the lower one (right ventricle) to also fail. When that happens, blood backs up into the venous side of the system, pooling fluid and blood that leads to a large, pear-shaped belly (ascites). This belly enlargement is not all due to free fluid in your dog’s abdomen – your dog’s liver and spleen are also becoming enlarged – congested with blood due to sluggish circulation.

These events cause many other things to happen. Your pet’s heart rate speeds up (tachycardia). Enzymes are released that constrict some blood vessels (increased vascular resistance and tone). Chemical changes occur as well – (release of angiotensin-converting enzyme) and rising aldosterone hormone levels released by your dog’s adrenal glands result in even more fluid and sodium retention. Rather than helping correct the situation, these events actually make your pet’s pulmonary edema problem worse. These events occur slowly and at a different rate in each dog. Dogs with mild to moderately enlarged hearts often show no signs of illness at all. The first sign might just be a little reluctance on the part of your dog to play as actively as it once did. You might just attribute that to its advancing age. When owners finally bring their pets to their veterinarian, it is usually because of that dry cough I mentioned earlier, which might be accompanied by gagging. These coughs tend to be worse when your dog is lying down and at rest.

More About These Signs

I mentioned that most owners find out that their dog has a heart murmur during one of its yearly routine health checkup. A listen with a stethoscope should always be part of your dog’s yearly “wellness” examination. What you tell your veterinarian about your pet (its medical history and life situation) is just as important as your veterinarian’s hands on examination. As I mentioned earlier, early heart issues only provide subtle clues that something is amiss. When your pet is relaxed at home it often shows symptoms that it won’t exhibit to your veterinarian during the office call. There are certain buzzwords that set a veterinarian to thinking about your pet’s heart: “more tired than usual”, “less active”, “chronic cough” “more panting”, “more gagging”, “more reluctant to climb steps than before”, or have trouble finding a comfortable sleeping position at night. You might mention, or your vet might observe, premature graying hairs on your dog’s muzzle and paws. Some dogs chill easier due to their poorer circulation.

With your dog’s history in mind, your veterinarian will probably check your pet’s gums for evidence of poor circulation (bluish or grayish gums = cyanosis) and its capillary refill time (CRT) is an indication of normal or sluggish blood flow. Observing your dog’s respiratory rate and the force and regularity of its pulse, as well as listening to your pet’s heart through a stethoscope are standard procedures during an office visit – or should be. Stethoscopes have been around since 1816; but they still provide an amazing amount of useful information to your veterinarian. Stethoscopes easily detect heart murmurs and give a clue by sound location and tenor as to which heart valve might be involved. Stethoscopes can detect excess fluid in the lungs (pulmonary edema) and judge the adequacy of your dog’s heart’s electrical system (by detecting arrhythmias).

Dog owners and physicians inexperienced in listening to the hearts of dogs or checking their pulse, sometimes confuse the normal fluctuations in canine heart rhythm (sinus arrhythmia) with pathological arrhythmias. The heart rates of healthy dogs are much more likely to increase with every inspiration than the heart rates of people. Some veterinarians assign a loudness number to your pet’s heart murmur if one is present. The faintest murmur is given a 1 and the loudest a 6. By the time a mitral valve murmur is a 6 you can often even feel its vibration over your dog’s left chest.

Some dog owners will put off seeing their veterinarian until their dog’s heart problem is more advanced. Those dogs have all or many of the symptoms I mentioned – but they are more profound. The gums of their mouth are redder and the blood vesicles of the gums more prominent and spidery (injected). Their gums and tongue might turn purplish (cyanotic) when the dog exerts itself. The dog might actually faint when exited or stressed. Heart murmurs tend to be louder, their lungs tend to give sounds that indicate excessive fluid buildup (moist rales). A jugular pulse is often observable on your dog’s neck. Their arterial pulse, palpated in their groin, is weak and thready and their heart rate is elevated. In these advanced stages, their heart beat is often irregular, and some beats heard over the heart may not be felt in its femoral area (groin) (=a pulse deficit). Although the dog may have an enlarged tummy, its prominent ribs and spine show that its body has lost considerable muscle mass (=sarcopenia). Pooled fluids and distended organs can deceptively keep your dog at its traditional weight on a scale.

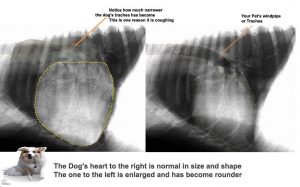

Chest X-rays

When your veterinarian’s physical examination and your dog’s history cause your vet to be suspicious of a heart problem, the next things usually suggested are chest (thoracic) X-rays or a cardiac ultrasound examination or both. Your veterinarian needs to see how much space your pet’s heart occupies in its chest, the shape of its heart (cardiac silhouette) and the condition of your dog’s lungs. I mentioned that failing hearts enlarge and become rounder (globular) in their outline. When fluid pools in the lungs or their surrounding, the image of the heart and lungs tend to be blurred (= a ground glass appearance). In early CHF, your veterinarian will also be looking for evidence that your dog’s left atrium is enlarging, If the heart’s shadow (its image) occupies more than the 3rd to the 6th rib spaces on the x-ray the heart is larger than it should be. If the increase in heart mass (size) has forced your dog’s windpipe (trachea) upward, as it commonly does, that upward pressure, along with any lung fluid accumulation, is what accounts for its cough.

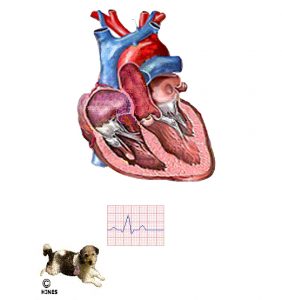

EKG = ECG = electrocardiogram

You might have had one of these multi-wired machines applied to you. EKGs measure the minute (tiny) electrical impulses traveling through the heart that allow it to beat rhythmically. Veterinarians rely on electrocardiograms to detect early heart electrical abnormalities. When the portion of the EKG displayed on a monitor or paper tracing called the QRS complex lengthens and increases in height (amplitude), it generally signifies left ventricular heart enlargement. In congestive heart failure, heart rates are often faster than normal as well and can also display premature contractions and abnormal or irregular rhythm. Sophisticated interpretation of EKG results requires training beyond that of most veterinarians in general practice. Fortunately, online services to help interpret results and suggest options are available to assist your dog. (see here)

Cardiac Biomarkers, Blood Tests

Sometimes, it can be difficult for your veterinarian to distinguish between problems that originate in your dog’s heart from problems that originate in its lungs or elsewhere in its body. In those cases, one of two blood test can be very helpful. These tests detect a marker chemical (a hormone) that is released by damaged hearts. I mentioned them earlier. The tests are ones that your regular veterinarian can run before deciding if it would be wise for your pet to be referred on to a veterinary cardiologist. Like most tests, these have their limitations. (read here) They are fine as a rule-out test for heart disease when they come back normal or a confirmation of heart disease when significantly elevated. But results can be in a gray or intermediate area where interpretation is difficult and the significance of the results unknown. Both Antech Diagnostics and Idexx Laboratories, the two largest independent American veterinary diagnostic laboratories, offer these tests. Antech’s is called Cardio-BNP and Idexx’s is called the proBNP test.

Standard blood chemistry tests and urine tests are usually normal until heart disease in a dog is well advanced. When any of those routine tests do become abnormal, it is usually because other body organs have become starved for oxygen or congested with pooling blood. Although routine blood tests cannot diagnose heart disease, they do let your veterinarian know how well your pet might tolerate the heart medicines he/she have at their disposal. They are also wise to run periodically during treatment for possible negative reactions to medications.

Echocardiography Heart Ultrasound, ECHO

Visualization of your dog’s heart as it is actually beating (in “realtime“) is the most informative way for your veterinarian to evaluate your dog’s heart health.There are three kinds of echocardiographic machines, M-mode (a single beam), two-dimensional (a cross-sectional “slice” of the beating heart) and 3-D echocardiographs that combine a doppler to assess speed of blood flow and pressure. The last is the most sophisticated and, in the hands of a skilled veterinarian, yields the most information. Doppler ultrasound is now the standard throughout human medicine in cardiology, blood clot and aneurysm detection, and restricted blood flow. (read here) When the operator has that training, a great deal of knowledge can be gathered about your dog’s current heart condition Using these machines, each of your pet’s heart valves can be measured as to its thickness and shape. One can also view how far the valve is pushed into abnormal positions as the heart beats (e.g. valvular prolapse) and how much it fails to open and close. The amount of blood flowing in the wrong direction (regurgitation) and the increased blood volume of a weakened heart are also evident.

Heart Terminology

What Medications Might Help My Dog?

No known medication(s) will repair damaged hearts. Valvular heart surgery is an option for a few dogs. I explain more about that at the bottom of this page. Stem cell approaches are still in their infancy with their benefits unproven. (read here) The medications your veterinarian does have should allow your dog to live more comfortably for a time. Hopefully, a long time. We concentrate on giving your dog medications that help eliminate excess fluids leaking from its sluggish circulation (= diuretics), drugs that decrease the pressure (work load) your dog’s heart must pump against (= ACE inhibitors), and drugs that increase the force of its heart contraction (= positive inotropes). The positive inotrope most frequently dispensed by veterinarians is pimobendan (Vetmedin®). I’ll go over them in that order. In late-stage heart disease or whenever necessary, veterinarians might also give your dog medications to keep its heart’s electrical system running as smoothly as possible. In most cases, more than one type of medication need to be given so that all these problems can be addressed.

Diuretics

Diuretics accomplish the first goal. When effective, they rid your dog’s chest and abdomen of excess pooled fluid. We used to call them “water pills”; but there is more in these fluids than water. They also contain a considerable amount of albumin protein and minor amounts of all the other constituents of your dog’s blood serum. Diuretics decrease pooled fluid through their effects on your dog’s kidneys by encouraging your dog to urinate. Diuretics are very effective in lessening coughs and respiratory distress when lung fluid buildup (pulmonary edema) is the underlying cause. The most commonly used diuretic in dogs (and humans) with heart issues is furosemide (Lasix®). The diuretic dose and the frequency it needs to be given will be quite different from one dog to another depending on the severity of its condition. Giving too much or too frequently during the day can dangerously dehydrate your pet or lead to kidney damage.

Furosemide (Lasix®)

Furosemide diuretic has been a mainstay treatment for CHF in dogs for many years. It is very effective in flushing excess fluid out of your pet’s body and, in most cases, causes relatively few side effects. It and similar drugs like bumetanide (Bumex®) are called loop diuretics because they do their work at small tubular loops (the loops of Henle) that are part of the filtering apparatuses of your dog’s kidneys. Dogs taking Lasix®, particularly when the drug dose and frequency are high, need to have their blood potassium level and kidney function monitored every few months, and they need to be observed for signs of dehydration. Pets that start furosemide for heart issues generally stay on it for the remainder of their lives. The improvement you see in your pet, once it begins taking furosemide, can be dramatic. As fluid drains from its lungs, its cough might rapidly go away, and it should breathe more easily. The amount of fluid pooled in its abdomen should also decrease. Remember however that this drug does not improve your dog’s heart function. It does its helpful work in your dog’s kidneys. When your dog begins taking furosemide, you should notice that it is drinking and urinating more. Do not restrict your pet’s access to water – give it all it desires. You will have to make arrangements for your dog to relieve itself during the night. I have not encountered problems when I limit a dog’s access to water in the evening and replace their water bowls in the morning in an attempt to help both of us sleep through the night – but that is something you need to discuss with your veterinarian. As I mentioned, on high doses of furosemide or other loop diuretics, your dog might require an oral potassium supplement.

Spironolactone (Aldactone®)

When a high-end (near the maximum safe) dose of furosemide is no longer sufficient to control fluid buildup in your pet’s lungs (=pulmonary edema) and/or its tummy (=ascites), your veterinarian might add another diuretic, spironolactone, to its medication plan. Spironolactone has the advantage of not depleting your dog’s potassium reserves. You need to be patient. Unlike furosemide, it takes 2-4 days for the full beneficial effects of spironolactone to be achieved. Spironolactone can increase the toxicity and effects of digoxin, so if your pet is taking digoxin, its digoxin dose might need to be lowered. Spironolactone can also increase serum potassium which can also be dangerous. To monitor your dog’s potassium level, a blood sample needs to be periodically taken and measured for serum electrolytes (and kidney function). That is often done on the 3rd or 4th day after beginning the medication, the 7th day and periodically thereafter.

Thiazide diuretics

Hydrochlorothiazide or chlorothiazide are alternative options to spironolactone that your veterinarian has at his or her disposal when furosemide is no longer sufficient to keep your dog’s fluid buildup under control.

ACE Inhibitors (angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibitors)

ACE inhibitors increase the rate that blood can flow throughout your dog’s circulatory system.The most common ACE Inhibitor medication used to treat CHF in dogs is enalapril (Enacard®/Vasotec®). But alternative ACE inhibitors, benazepril, captopril and lisinopril are also options. Drugs in this class differ in their absorbability when given orally and in the stress they put on your dog’s kidneys and liver. (read here) The effects of ACE inhibitors on your dog are not immediate. It can take a week or two before you see full improvement. These medications all decrease the effort your pet’s heart must exert to pump blood throughout its circulatory system by relaxing and expanding blood vessels throughout its body. They do this by reducing the formation of a hormone in the lungs, angiotensin II, that increases your pet’s heart’s workload (=peripheral or systemic vascular resistance). Elevated angiotensin II is also undesirable for failing hearts because it increased the production of another hormone your pet’s adrenal glands produce, aldosterone, that causes sodium and water retention and high blood pressure (the RAS system). In doing so, ACE inhibitors lower blood pressure and decrease salt (sodium) and water retention. Your dog’s dose needs to be periodically adjusted in response to the improvement you see or desire to see in your dog.

Dogs in heart failure often have fragile, decrease function, kidneys as well. Since ACE inhibitors, as well as diuretics, occasionally have negative effects on the kidneys (azotemia), your dog’s kidney function in heart failure needs to be checked before these drugs are given and then rechecked periodically. Dose size and frequency needs to be kept to the minimum that yields positive results and the diuretic dose may need to be adjusted downward as the ACE inhibitor dose required increases. ACE-inhibitor medications have the opposite effect of furosemide diuretic, they tend to raise blood potassium. Occasionally, reaching dangerously high levels. This is another reason periodic blood monitoring is so desirable. Vomiting and a poor appetite are also occasional side effects of ACE inhibitors. Your veterinarian can usually solve all those problems without having to discontinue any of your pet’s medication. Enalapril is approved for once-a-day use in dogs; but it seems to work more effectively for me when the pet’s total daily dose is divided and given half in the morning and half in the evening. The drug will occasionally cause nausea, diarrhea and a loss of appetite. If the dose is higher than necessary, low blood pressure can also result, leading to listlessness and weakness.

Benazepril (Lotensin®, Fortekor®) that I mentioned above, is another ACE-inhibitor quite commonly given to dogs with congestive heart failure. Like enalapril, it is usually given along with a diuretic and like enalapril, it can be given with or without food. The ability of a portion (~50%) of benazepril to leave your dog’s body through its intestinal liver bile perhaps makes it a better choice than enalapril in dogs with kidney disease (all enalapril must leave via your dog’s kidneys and urine). In humans, the danger of compounding pre-existing kidney problems appears slightly less for benazepril than it does for enalapril. Benazepril is also sold as a custom-prepared topical, transdermal, cream. I do not know how effective that might be. The primary customers are probably cats because they are so hard to pill.

Is There Any Benefit In Beginning ACE Inhibitors Before My Dog Shows Signs of Heart Failure?

This is currently debated. One might assume that reducing your dog’s heart workload before severe damage occurred might postpone that damage. The only study I know of in dogs did not find that to be true. But that was a study of Cavalier King Charles Spaniels – a breed with multiple, genetic, health-related problems. So, some veterinary cardiologists go with their instincts and prescribe ACE-inhibitors before your pet’s heart has deteriorated to the point where the dog needs them. That is much the same way that ACE medications have been used by physicians to ward off strokes. (read here) Studies in other animal species have not found that strategy to be advantageous. (read here)

Hydralazine

Hydralazine is not an ACE-inhibitor, but it has similar effects. This potent medication dilates blood vessels and, in so doing, lowers the resistance that your dog’s heart must pump against to supply fresh blood to its body. Because the drug can cause dangerously low blood pressure and a racing heart beat (tachycardia), it must be used cautiously. It is best given and monitored in an animal hospital environment under close veterinary observation until the drug’s effects on your dog become known.

Positive Inotropes

Pimobendan (Vetmedin®)

Pimobendan (Vetmedin®), combined with a diuretic and ACE inhibitor, has rapidly become the standard, first line treatment for advanced congestive heart failure in dogs. All positive inotropes like pimobendan increase the strength of the contractions of your dog’s heart. Ionized free calcium is an important part of the mechanism of all muscle contractions in the body – including the heart. The force of heart muscles contraction is related to the amount of calcium ion present in your dog’s circulation. Pimobendan increases your dog’s heart muscle sensitivity to the ionized calcium that is already present there. Similar to ACE inhibitors, Vetmedin® also opens up (dilates) blood vessels throughout your dog’s body easing resistance and pressure within the circulatory system. That also improves the efficiency with which your dog’s heart functions as a pump. In one clinically controlled trial, dogs with congestive heart failure survived on average of 42 days without Vetmedin and 217 days when Vetmedin® was part of their treatment plan.

Digitalis compounds – Digoxin/Lanoxin® & Digitoxin

Digoxin and digitoxin are two other drugs in the positive inotrope group. They are quite similar to each other, but digoxin needs more frequent doses than digitoxin and digitoxin is less dependent on having good kidney function. Both will increase the force of your dog’s heart contractions by increasing its heart’s sensitivity to blood calcium. But both of them have can have major side effects. Those include vomiting, depression, refusal to eat and heart rhythm abnormalities. Dogs receiving either medication need to be very closely monitored by your veterinarian and their dose finely adjusted to their needs and their ability to tolerate either drug. As I mentioned, digoxin and digitoxin are slightly different in that the first is excreted through your dog’s kidneys and the second is metabolized by its liver. So, digitoxin is probably a better choice when your dog’s kidney function is poor. I have seen too many cases of toxicity in dogs given these products to be a fan of either drug. When they are given, it needs to be under the supervision of a veterinary cardiologist. (read here)

Antiarrhythmics (Drugs to stabilize your dog’s heart beat)

Dogs with irregular heartbeats or fainting episodes (syncope) might benefit from this group of medications. Their use must be carefully monitored, and they are usually begun only after fainting episodes, or serious heart beat irregularities detected in your dog’s electrocardiogram or through the use of a Holter monitor which records your dog’s heart rate and beat regularity over time. The two most commonly used antiarrhythmics in dogs are still probably sotalol or a combination of mexiletine and atenolol.

Beta Adrenergic Blockers (ß-adrenergic blocking drugs)

The best-known drugs in this class are propranolol and the atenolol previously mentioned. These medications protect your dog’s heart from excessive levels of stress hormones (i.e. catecholamines, adrenaline and noradrenaline) that are often present in the blood of dogs in advanced congestive heart failure. In doing so, they lower blood pressure, reduce the heart’s oxygen demand and also help protect against heart beat abnormalities (arrhythmias). These drugs appear more effective in combating the sudden heart deterioration of dilated cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation when combined with digoxin.

Are There Other Drugs That Might Help My Dog?

Yes

Calcium Channel Blockers

The most commonly used drug in this class is diltiazem. Diltiazem is another drug that increases the diameter of your dog’s blood vessels (a vasodilator). That increases the ease with which blood flows, so that your dog’s heart doesn’t have to work as hard. But the drug is used primarily in the acute forms of heart failure that are seen most often in large breed dogs – the dilated cardiomyopathy issue I previously linked to, as well as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. which veterinarians see more frequently in cats than in dogs.

Drugs To Help Your Dog Breath Easier (Bronchodilators)

Theophylline and aminophylline are the two most common drugs in this group dispensed by veterinarians. They both work by increasing the diameter of the small passages (bronchioles) in your dog’s lungs. That should allow your dog to breathe more freely. Both also seem to reduce the frequency of fainting in some dogs in the late stages of congestive heart failure.

Cough Medicines

Cough suppressants are generally not necessary in dogs with CHF. They usually respond better when given diuretics like Lasix® to reduce excess lung fluid congestion. Cough suppressants only mask a cough. However, if x-rays show that your pet’s lungs are clear of fluid and the coughing is due to an enlarged heart pressing on your pet’s windpipe (trachea), then a cough suppressant might be helpful. When used, the most commonly dispensed cough suppressant that actually works is a combination of hydrocodone and homatropine. Medications such as dextromethorphan are considerably less effective.

Nutritional Support

We want to do everything in our power to keep our beloved pets with us as long as we can. Dog food companies that are now mostly multinational conglomerates with their fingers in many pies know that. They are quick to market products likely to please us. But the products they market are not necessarily science-based. (read here & here) They are more likely to echo whatever dietary trends are current in the popular press. They also aim their marketing heavily to veterinarians. The only study that ever claimed to find any of those diets helpful in mitral valve heart disease in dogs (Royal Canin’s Early Cardiac™) was paid for by the Waltham Center, a division of Mars Inc., which is also the manufacturer of that dog food. (read here) Does McDonald’s ever suggest that Burger King’s hamburgers are better? All mayor pet food companies now market “heart diets”. They are all lower in sodium and higher in profit. Particularly so when forced to buy these dog foods from your veterinarian. High sodium level dog food has never been identified as a cause of heart disease in dogs nor have low sodium diets been identified as helping dogs with heart disease. When low sodium diets were given to dogs in an attempt to lower their blood pressure, it was unsuccessful. (read here & here) Lowering blood pressure is the chief reason low sodium diets are suggested for people with heart disease. But these companies know that you know that low sodium diets are also suggested for human heart issues. They then throw in ingredients such as fish oil, glucosamine, green tea extracts, marigold extracts and extra l-carnitine, taurine and antioxidants. Of those, only the taurine and carnitine have been proven to be helpful and that was only in dogs that developed DCM, not the much more common congestive heart failure this webpage is about. The DCM dogs that did benefit were all confirmed to have been deficient in taurine. (read here). That said, there is no harm in feeding these diets to your dog with congestive heart failure.

Coenzyme Q & Omega-3 Fatty Acids

Coenzyme Q10 is a natural substance that is involved in the body’s energy generation. Its level in our bodies naturally declines as we age. Organ meat such as beef heart, kidney, and liver is rich in Coenzyme Q10. It is also found in high levels in the red flesh of mackerel and is present in tuna and salmon as well. Much of Q10 is destroyed by cooking. It is sold where human supplements are sold. The benefits of its use in humans with heart disease is problematic. Some studies found it beneficial (read here) but others did not. (read here) Mice with a Q10 deficiency actually lived longer than those that had normal Q10 levels. Some human cardiologists recommend coenzyme Q for heart disease, other cardiologists feel there is not enough evidence one way or the other. (read here) This is another one of the product out there that there is no harm in giving to your dog in reasonable amounts. But your dog might appreciate some lightly cooked, deboned, mackerel or beef liver instead – I know my dog would.

Omega-3 fatty acid supplements are in the same category. Deboned mackerel is a great source of them too. If you purchase these things in capsules, buy them at a human health food store or supermarket. Products sold for people tend to undergo a higher level of scrutiny than those sold for pets.

Helping Your Dog Maintain A Healthy Body Weight

Over time, dogs with CHF tend to lose muscle mass (cardiac cachexia). Their abdomens may still seem normal to you and their weight may not have changed, but that is only due to a congested enlarged liver and pooled fluids. Their ribs and spine become more prominent due to muscle wasting. All of this is the result of their low cardiac output. It is important that you do everything you can to encourage your dog with congestive heart failure to eat. High-quality meat protein and vitamins need to be high in your dog’s diet. Geriatric pets often have tooth and gum issues – so offering your dog its food in a softened, freshly made at home or canned form is often best. You might look into Entyce® as an appetite stimulant. If you want to add your observations on Entyce® in your dog with heart disease to the Entyce blog, let me know.

Additional Procedures And Treatment That Might Eventually Become Necessary – Oxygen

When your dog can no longer catch its breath after exertion, or during heart emergencies, supplemental oxygen might be helpful. All pet emergency centers have specialized sealed cages to administer oxygen to pets. But trips to an emergency veterinary center are stressful to your pet and to you and expensive. You can improvise a clear oxygen “tent” at home for smaller dogs or use an improvised or commercial veterinary face mask for larger dogs. PURE OXYGEN CAUSES ORDINARY THINGS IN YOUR HOME TO BECOME VERY FLAMMABLE. If you contemplate using pure oxygen at home for your dog, have a human or veterinary respiratory therapist instruct you on its use. A fire extinguisher might also be a wise purchase. Small metalic home oxygen cylinders do not last long and are quite expensive to refill and recertify. I suggest you just purchase a home oxygen concentrator and follow the safety instructions provided by the manufacturer.

Removal Of Excess Chest And Abdominal Fluids

Dogs become quite uncomfortable when there is excess fluid in their chest or abdomen that restricts their normal respiration. Draining that fluid (thoracocentesis and abdomenocentesis) can give your dog temporary relief. It is generally performed by veterinarians in emergency situations to gain more time for the positive effects of diuretics, like furosemide and other heart medication to take effect. If you recall, I mentioned that leaked fluid (ascites, dropsy fluid) contains a lot of albumin protein. When your dog’s abdomen is drained too frequently, your pet’s blood albumen content can drop dangerously below normal. That needs to be monitored. When diuretics didn’t succeed on their own, it is usually because your dog’s kidneys and/or liver are damaged as well as its heart. (read here)

Exercise Restriction

Our pets are so happy and excited to see us when we get home that they gladly overexert themselves. As much as your dog would enjoy it, encouraging your pet to “work its heart out” at its maximum capacity is not a good idea when congestive heart failure is an issue. Modify the style of your returns home, your play-times and your pet’s lifestyle to minimize its daily exertion. It is your closeness and your touch that means the most to your dog’s happiness.

How Much Longer Will My Pet Live?

Dogs with mild to moderate heart disease can have a good quality of life for many years. Every dog differs in the rate at which CHF advances and no statistics are available for me to provide you with. In humans diagnosed with congestive heart failure, half of the patients are alive 5 years after their diagnosis. The shorter natural lives of our pets shorten that available time window. How suddenly the symptoms of a heart problem appeared in your pet also tends to predict survival time. The more sudden the onset, the shorter your dog is likely to live. In dogs with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) which eventually leads to congestive heart failure as well, the average canine survives only 4.2 months. (read here) However, when a valve failure is the underlying cause of CHF, dogs tend to survive much longer.

That will always vary from case to case. But, with the exception of mitral valve surgery, the end result is never a cure. The outlook and longevity of your dog moderately improves when its heart is enlarged but no electrical (rhythm) abnormalities are present. Heart size increase is a relatively good predictor of the disease’s progression, but no better than your observations of your dog’s energy level and respiratory rate. Periodic pulse oximetry accurately tracks the rate of decline of human heart function. It is plausible that it does in dogs too, but to my knowledge, no one has studied that. You can keep a diary of periodic oximeter reading on your pet’s ear or tongue if you wish. If you do, Let me know the results.

Your nursing care, and your veterinarian’s assistance are key factors in maximizing your dog’s lifespan once CHF has been diagnosed. All dogs on therapy for CHF need to be reexamined every 3-6 months and their therapies adjusted according to the results. Any change for the worse or improvement is something your veterinarian will want to know immediately. It is wise to include a blood chemistry panel, ECG, and perhaps chest radiographs – but your assessment at home of your dog’s energy level and general comfort are just as valid indicators of when medicines need to be added, changed or their doses adjusted.

Is Open-Heart Surgery An Option For My Pet?

That is sometimes an option for well-to-do dog owners whose pets have developed mitral valve attachment disease. When the anchoring fibers (chordae tendinae) that hold your dog’s left upper heart valve in place, have torn, stretched or contracted. (read here) Veterinarians at Nihon University in Tokyo have perfected a procedure to correct that. (see here & read here) In the USA, I would discuss that option with cardiologists at the Veterinary School in Davis CA.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.