Chronic Digestive Problems In Your Dog IBD

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) AKA: Protein-losing Enteropathies, Chronic Enteropathies, Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Chronic Diarrhea

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is not one disease, it is many – a catch-all term veterinarians and physicians used to describe many conditions with similar signs but very different primary causes and presentations. That is why one treatment plan is never appropriate for the entire panorama of dogs that deal with IBD-like issues. Current thought among research physician is that many cases of IBD (and Crohn’s disease) are the result of an immune system error involving CD8+ T RM lymphocytes, one of a subset of the defensive cells of the immune system. (read here & here) The theory is that the ones that reside in the walls of the intestines (tissue resident CD8 T cells) have mistaking harmless bacteria residing in the colon for dangerous pathogens that need to be destroyed. To hasten bacterial destruction, these cells release inflammatory cytokines.

That so many terms are used to describe these situations can be quite confusing. They include IBD, chronic colitis, colitis, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), lymphocytic-plasmacytic enteritis, eosinophilic enteritis, regional enteritis, granulomatous enteritis and spastic bowel syndrome – all depending on what particular symptoms predominate in your dog and what region(s) of its digestive tract are most affected. Some rely on what pathologists see in the biopsy samples taken from your dog and what your veterinarian guesses the underlying causes might be. For the purpose of this article, when I use the word IBD – it pertains to all of them.

Basically, any time your dog’s intestines remain irritated for long periods (greater than ~ 3 weeks) without an infectious, parasitic or toxic cause, some form of inflammatory bowel disease is the cause:

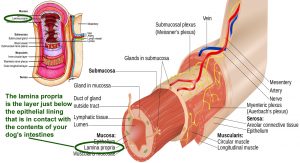

(A) Your dog’s intestines are inflamed (particularly the lamina propria layer)

(B) The site of the problem is your dog’s bowel (intestine).

Are There Diseases And Issues Other Than IBD That My Veterinarian Would Want To Rule Out?

Yes, there are quite a few.

Some dogs have idiosyncrasies that lead them to eat stuff they shouldn’t – chewing on sticks, eating leaves, excessive grooming, or getting into the garbage day after day. Others have family members and children who slip the dog stuff they want – but shouldn’t have. It is such a hard thing to resist. That can cause chronic loose stools – even containing blood – that cannot be easily distinguished from inflammatory bowel disease. It is not unusual for dog owners not to make the connection that these “dietary indiscretions” are occurring. Sometimes stool from these dogs need to be collected on various days and passed through a screen or sieve by you or your veterinarian to identify offending materials that are irritating your dog’s intestines. Some of these dogs eat strange stuff because they are just quirky. But some probably have a deranged appetite (pica) – with IBD as the underlying cause as occasionally occurs in humans.

As dogs mature from puppies, they develop a significant degree of natural immunity to hookworms and roundworms if they are housed in hygienic conditions and well-fed. Both hookworms and roundworms can cause persistent diarrhea, mushy or soft stools. Your vet can easily find evidence in the dog’s stool when these worms are present in their intestines in their adult form. Whipworms and strongyloides worms, on the other hand, are considerably harder for your veterinarian to diagnose through stool specimens. They both can be the underlying cause of chronic intestinal problems in mature dogs and have symptoms that mimic IBD. Whipworms are best diagnosed through a PCR test. when suspected, strongyloides best treated with fenbendazole moxidectin or ivermectin. (read here)

Giardia parasites can also cause transient, intermittent or persistent diarrhea. Metronidazole (Flagyl®) is often the treatment of choice for giardia. However, when your dog develops persistent or reoccurring diarrhea (more than 4-6 days) and giardia are seen microscopically in their stool, there is most likely some underlying defect (often IBD) that is allowing the giardia parasites to prosper. Kennels, pet daycare centers, doggy parks and exposure to sewage-contaminated water are common places for your dog to be exposed to the giardia. The parasite is not particular as to the species of animal it infects. It moves back and forth between species. (read here)

Dogs with underlying chronic liver or pancreatic disease share many of the symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease. When pancreatitis affects the portions of a dog’s pancreas that produces digestive enzymes chronic diarrhea and changes in intestinal flora are a common result. (read here) When primary bile acids are not properly recycled through your dog’s intestine due to liver problems, diarrhea can result as well. So, your veterinarian will probably want to run some liver and pancreatic tests to rule out those organs as contributing to your dog’s problem.

Anything that partially obstructs food flow through your dog’s intestine (such as a stricture, tumor or foreign object) can cause abnormally shaped stools, diarrhea or intermittent diarrhea and constipation. X-rays and ultrasound help rule those issues out or contributory.

What Signs Might I See If My Dog Has An IBD Issue?

The most common complaint that bring IBD dogs in to their veterinarians is persistent loose or mushy stools, straining (tenesmus) and diarrhea – often leading to accidents in the house. This occurs because the pet’s irritated intestines are contracting too fast (peristalsis). When consumed food and liquids passes through your dog’s intestine too rapidly, it does not give the colon time to remove sufficient water. Soft and frequent stools eventually Irritation the anus and do not allow the dog’s anal sacs to empty. causes straining and scooting. (read here) The walls of your dog’s colon are rich in mucus-secreting cells. These cells over-produce mucus when irritated, hence the “mucousy”-coated stools – sometimes with flecks of blood – that are a common sign of IBD. When the chronic inflammation of IBD affects higher areas of the intestine (jejunum and ileum) many dogs loose weigh as well as appetite. Resulting nutritional deficiencies can rob their coats of luster.

In IBD, not all sections of your dog’s intestinal tract will be affected equally. When the upper portions are involved (closer to the stomach), the dog may vomit. This sort of higher intestinal level involvement tends to produce less frequent, large, bulky and watery stools. Loss of appetite and weight loss are also more likely to occur when IBD inflammation is high in the intestine. Lower level involvement (colon) is usually associated with more frequent, smaller stools, straining, mucus and flecks of recognizable blood. Most often, multiple areas of the intestines are inflamed – with the majority of signs associated to whichever area is suffering the most damage.

In general, pets with the higher forms of IBD look more ill. That is because by the time food reaches the lower portions of the intestine, most important nutrients have already been absorbed.

Persistent loose stools inflame your dog’s anus often causing scooting and repeated attempts to defecate that can be mistaken for anal sac disease. Straining to defecate can also easily be mistaken for constipation. A veterinarian’s check of these dogs will confirm that the pet’s anal sacs are enlarged and sensitive. But that is just the consequence of passing stools that are not firm enough to empty (express) the anal glands as the stools pass out the rectum – not evidence of primary anal sac disease.

It is not unusual for tummy gurgling (borborygmi), flatulence, bloating and discomfort to also accompany IBD issues in dogs.

In the most severe form of IBD = protein-loosing enteropathy (PLE), blood levels of albumin and globulin (the dog’s major blood proteins) drop due to their leakage into the intestine. Besides appearing emaciated (very thin) these dogs often have potbellies due to the leakage of serum fluids from their blood vessels into their abdomens (ascites) (blood proteins help confine body fluids to the circulatory system where they belong). You can read more about protein-loosing enteropathy farther along in this article.

The symptoms of IBD often wax and wane (fluctuate) based on current environmental stress, things like separation anxiety, concurrent health issues, and medications administered for other health issues (e.g. antibiotics, NSAIDs, corticosteroids, etc.). Eating things they ought not eat is usually sufficient to bring on an attack and for unknown reasons, interest in eating non-food items is a hallmark symptom of IBD.

What Is Happening In My Dog’s Intestines?

Movement of food through your dog’s intestines are governed by its autonomic nervous system (the dog’s “second brain”) working through the rhythmically pulsing of smooth muscles that form the outer layers of your dog’s stomach and intestines. The particular nerve that sends these signals from your dog’s brain is its vagus nerve.  But this nerve can and does function independently of the conscious brain. (read here) Smooth muscle fibers (cells) are also stimulated into action by chemicals released during inflammation (e.g. cytokines aka “substance P”). That cytokine release occurs in the layers of tissue that are in actually contact with the food and bacteria present within your dog’s intestine. (read here) Increase in the speed of those pulsations is the cause of the diarrhea we observe in IBD. I have simplified the explanation of a very complex interaction.

But this nerve can and does function independently of the conscious brain. (read here) Smooth muscle fibers (cells) are also stimulated into action by chemicals released during inflammation (e.g. cytokines aka “substance P”). That cytokine release occurs in the layers of tissue that are in actually contact with the food and bacteria present within your dog’s intestine. (read here) Increase in the speed of those pulsations is the cause of the diarrhea we observe in IBD. I have simplified the explanation of a very complex interaction.

The “war” that is liberating those cytokines changes the architecture and components of those layers closest to the bacteria and food in your dog’s intestines. The finger-like, nutrient-absorbing intestinal villi become distorted or blunt in their shapes. Open ulcers can appear; and the layers just below them pack with defensive cells of the immune system (macrophages, lymphocytes/plasma cells, neutrophils and eosinophils). In some dogs with IBD, these changes are minimal or only occur now and then during flare-ups. The longer your dog has suffered from uncontrolled IBD, the more pronounced these symptoms are likely to be.

Changes In The Bacterial Residents Of Your Dog’s Digestive Tract = Dysbiosis

Your dog was designed to carry within it, an enormous zoo of microbes (its microbiota). The vast majority live within the dog in harmony – the dog providing them nutrients and refuge and the microbes providing the dog with vitamins, critical digestive enzymes, detoxification of things ingested, recycling and modifying the dog’s metabolic wastes, and protection against pathogens encountered. Hundreds of different species of bacteria and fungal organisms are normally present in your pet’s digestive tract. Almost half belong to a group called firmicutes. About a quarter of a group called proteobacteria with bacteroidetes, fusobacteria and actinobacteria present in lesser numbers.

Many of these bacterial groups contain some “unhealthy” (to the dog) as well as “healthy” members. When things go well, the potentially “unhealthy” species are kept in check by the potentially “healthy” ones – with your dog’s immune system’s presentation cells assisting in the process.

When your dog has IBD, the species of microbes and their numbers found in your pet’s intestines change. The number of “good” species present tend to decline. It is unclear if the physical changes in the structure of your dog’s intestine that I mentioned earlier are the cause of this population shift or if the change in the microbe population results in the physical changes of the disease – the changes that result in diarrhea and other symptoms of IBD. Perhaps in some dogs the microbe change it is the result of the physical changes, perhaps in others it is the cause, perhaps a bit of both. Whichever, dogs with any form of IBD harbor different bacteria in their intestines than health dogs do. This unhealthy change in bacterial populations is called dysbiosis. Some associate that with the low quality and many additives in mass-produced dog food. (read here) The dysbiosis of IBD appears to even involve the virus (bacteriophages) that normally inhabit your dog’s intestinal bacteria population (there are a lot of these virus). (read here) These bacterial virus are generally considered by physicians and veterinarians to be harmless. But there are outlier opinions on IBD that challenge that decision. (read here & here)

Changes In Your Pet’s Intestinal Immune System – Mistaking Friends For Enemies

Your dog’s digestive tract, its skin and its respiratory system are the major portals through which diseases enter its body. So, it is natural for the bodies defensive soldiers – the immune system’s cells – to concentrate their resources just below the surface of those three areas. The function of some of those soldiers (primarily macrophages) is to kill those invaders. But the job of other sentry soldiers is to decide who is friend and who is a foe; what is self and what is foreign, what is a threat and what is not. Many believe that in pets with IBD, some of those soldiers (helper T cells) have made a mistake.

Are My Dog’s Breed And Genetics Factors?

Yes, it can be.

Any breed or mixed breed dog can develop IBD. But Weimaraners, Rottweilers, German shepherd dogs, Border collies and boxer breeds are noted for their increased susceptibility to IBD. Basenjis and Shar-Pei dogs have their own special forms of IBD (immuno-proliferative IBD). Boxers tend to suffer from a form called histiocytic ulcerative colitis while the IBD seen in Irish setters is thought by some to be triggered by a wheat gluten sensitivity.

Because dog breeds are formed on the basis of similar gene patterns, veterinarians and physicians alike have been searching for gene combinations that IBD sufferers have in common. The hope is that a better understanding of what those gene combinations are might offer better or earlier tests, and even alternative treatment plans. Dogs give research physicians a convenient window into problems us humans also face. In 2012, veterinarians in London ran a study that focused on a particular gene (TLR5) that is involved in deciding which bacteria are friend and which are foe. This gene is known to be inherited in variations (haplotypes) that appear to influence susceptibility to IBD in humans. This gene allows your dog’s immune system to examine a certain protein (flagellin) that allows many bacteria to move about. They found that German shepherd dogs that suffered from IBD were most likely to have certain (defective?) subtypes (SNPs) of this gene.

Great Dane dogs also suffer from more than their fair share of IBD. Unfortunately, in this breed, IBD often begins at a very young age. It is often misdiagnosed as a giardia problem – since giardia take advantage of dysbiosis. Since the treatment for giardia is quite similar to the treatment for IBD (metronidazole + a bland diet), they often get better. Great Danes are also the breed at highest risk of developing fatal stomach bloat. (read here) A 2016 study focused on how the Great Danes’ immune system responds to proteins found on the surface of all cells (the MHC) (cells of the dog’s own body and bacterial cells) when deciding which cells are self, which cells are friendly skin and intestinal flora and which are hostile. They found that two gene pattern at the Dane’s MHC tripled their risk of making incorrect ‘friend or foe” decisions when it came to intestinal bacteria. They also found gene combinations that protected against improper “friend vs foe” decisions. Although the study was focused on bloat, perhaps t adds to our understanding of IBD risk in that breed as well.

What Findings Would Make My Veterinarian Suspect IBD?

What Special Tests Might My Veterinarian Run?

Inflammatory Bowel Disease will be on your veterinarian’s diagnostic list as soon as you tell him/her about the symptoms your pet is experiencing: Long-standing diarrhea with or without vomiting, perhaps weight loss and increased mucus on the stools (sometimes with streaks of blood) are all suggestive of IBD. The vet’s focus will particularly turn to IBD when the other common causes of persistent diarrhea that I mentioned earlier in this article have been ruled out. Some will be ruled out by the history you give – some by the tests performed. In veterinary medicine, test and examination results are rarely a perfect match for any chronic disease (there are not that many “textbook” cases). So, it may take some time for your vet to sort things out. That is particularly true because, short of intestinal biopsies, vets don’t have any tests they can rely on with certainty to rule IBD in or out. So, the vast majority of IBD cases end up receiving the “diagnosis by successful treatment” approach. I will tell you about that “diet/probiotic/antibiotic/drug/biopsy” approach later.

During the veterinarian’s physical exam of your pet, he/she might feel thickened intestines and enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes surrounding them. The same abnormalities can sometime be seen in ultrasound examinations as well. Those changes are most common in long-standing, significant IBD.

Looking over notes from your previous visits, the veterinarian might notice that your pet has lost weight – or should weigh more than it does. Your vet will observe if your dog is one of the high-incidence breeds or a cross with one. The mean age of dogs in which IBD symptoms finally motivate dog owners enough to bring their pets to their veterinarians is about 6 years. Maybe your dog had bouts of indigestion and soft stools before that. Most IBD dogs did. But you wrote that off to what it ate that day, a sensitive stomach, stomach flu or something else, and it resolved on its own or with some kaopectate.

Generally, vets start with a fecal sample examination to rule out parasites, gauge the sufficiency of digestive enzymes or the presence of consumed trash. Some blood work to rule out pancreatic, liver or other systemic disease might be suggested. If the dog is depressed, running a fever or has a painful stomach, probably x-rays as well.

In most cases of IBD, your dog’s blood work results will be normal. Not so if the problem is long-standing and severe. In severe or long-standing cases, your pet’s blood protein level is often low due to your dog’s inability to absorb protein-containing nutrients and loss of blood protein leaking out through its damaged intestinal wall. In most cases of IBD your dog’s blood globulin (another blood protein) level will be normal or low. But in a few cases, globulin will actually be elevated due to immune system stimulation. If your pet has been vomiting persistently, its blood potassium level might be low as well. A few pets will have increases in their eosinophil white blood cell numbers. That can be a possible hint at a food sensitivity or parasitic problem rather than IBD or compounding IBD.

There are specific tests that veterinarians can have run to help confirm an IBD problem when doubts remain or when accepted treatments fail. We know that many or most dogs with IBD do not absorb sufficient vitamin B 12 (cobalamin). The same goes for their ability to absorb folate (folic acid, another B vitamin). Some veterinarians suggest that those tests, and others test run by the A&M GI lab, be run on your dog to firm up an IBD diagnosis. They might be more adamant about it if your dog is already showing signs of malnutrition, weight loss, low energy, and “unthriftiness” (cachexia). The gastrointestinal lab at Texas A&M veterinary school has pioneered the adaptation and interpretation of these tests to dogs.

Endoscopy and Intestinal Biopsies

None of the tests I have mentioned up to now will give your veterinarian as clear-cut a description of what is occurring in your dog’s intestine as having small snippets of tissue from various levels of its digestive tract examined microscopically by a veterinary pathologist. Those snippets of tissue are best obtains using an intestinal endoscope.

The procedure is expensive. Because of that, most veterinarians only suggest it be performed when response to treatment is poor, when the disease is advanced and life-threatening, when the diagnosis is cloudy, or when things like intestinal cancer are suspected. The veterinary specialist, will look for areas of the intestinal wall that look the most abnormal when deciding where to take the biopsy samples. So, the technique is not fail proof. One spot on the intestine may yield a biopsy specimen that shows a degree of inflammation and pathology or lack of it that a sample taken a few millimeters away does not show.

What Treatment Will Help My Dog?

With the exception of products like Imodium®, and Lomotil®, all the treatments veterinarians generally utilize for IBD are attempts to decrease inflammation in your dog’s intestines.

A New Diet

A New Diet

About half the cases of IBD markedly improve or resolve when a new diet designed for intestinal issues replaces your dog’s current diet. When they do, your pet’s form of IBD is called Food Responsive IBD (FRE). There are two dietary approaches that seem to work best:

One type (e.g. Purina’s HA®, Hills z/d diet ®and Royal Canin’s Hypoallergenic HP®) have been processed in ways (hydrolyzed) that reduce the likelihood that your dog’s immune system will react to the proteins they contain. Diets marketed as “easily digested” are not the same thing and probably less likely to be helpful. One study found that these forms of hydrolyzed diets are more likely to help IBD dogs than those that relied on the second type.

The second type relies on only containing protein sources that are new (“novel proteins”) to your dog’s immune system and therefore not offensive to it (yet). The protein in these types of dog food could be rabbit, duck, venison, fish etc. One can also prepare novel protein diets at home– preferably with the help of an online veterinary nutritionist. (read here) The same study that found hydrolyzed protein diets preferable to these novel protein diets found that of the novel proteins they tried, fish seemed the most beneficial. Try them for 3-4 weeks before deciding on their worth.

One study found an IBD dog’s response to the fiber level in its diet is quite variable. Some dog owners find that low-fiber diets are preferable (as is the case in humans); but fiber is also an essential nutrient for many of the “healthy” bacteria that form a dog’s intestinal flora. If you feed a commercial hypoallergenic diet, you are locked into the fiber content given on the label. If you prepare the diet yourself, you have more flexibility. A dog’s response to the fat content of its new diet is unpredictable as well.

I do not know how one might prepare hydrolyzed diets at home. But when attempting novel protein diets, making them at home might have advantages. Especially when your alternative is to feed canned dog food. Canned dog foods are about 75% water. For owner eye appeal, the pet food manufactures add large amounts emulsifiers to make their products appear thicker and meatier. Those emulsifiers include, carrageenan, guar gum, alginates, polysorbate-80, and lecithin – among others. (read here)

Hills uses corn starch to thicken their hydrolyzed intestinal diets, the other two use guar gum or carrageenan. Healthy bacteria rely on their position in the intestinal tract to thrive. It appears that emulsification of these bacteria within the gut is harmful to them. If you go to the NCBI index index and search for the effects of food emulsifiers on gut microbiota (“good” bacteria, yeast and protozoa) you will find 8 references on the influence of food emulsifiers on intestinal flora. None of the effects of emulsifiers were positive. So, you might stay with therapeutic dry kibble products if you feed off the Big Box store shelf. You can always moisten them.

Cans of dog food are often lined with BPA if they are not specified as BPA-free. BPA has also been implicated in intestinal dysbiosis and, in some cases, appeared to worsen IBD symptoms. (read here)

Prebiotics and Probiotics

Prebiotics and Probiotics

Prebiotics are complex carbohydrate such as fiber – a key source of nutrition for the “healthy” bacteria we want to prosper in your pet’s intestine. I mentioned earlier that your dog’s response to increased fiber in its diet is at best unpredictable, at worst problematic.

Probiotics are supplements that actually contain living bacteria – products like Purina’s FortiFlora® which is marketed as helping to reduce flatulence and “promote intestinal health”. They throw in some vitamin E, C and beta-carotene for good measure. None of these products contain more than one or two of the multitude of “healthy” bacteria that are required for a normal gastrointestinal flora (in the case of FortiFlora®, only one, a non-pathogenic variety of Enterococcus faecium). I advise you not give this product if you are evaluating the effectiveness of a hydrolyzed or novel protein diet because the main ingredient in it is animal digest and there is no telling what “animal(s)” that term refers to – nor their quality. Besides, one report exists that Enterococcus faecium supplementation has the potential to lower a dog’s blood folate levels – something that is often already a problem in some IBD dogs. (read here)

Loperamide Hydrochloride

Loperamide Hydrochloride

My Labrador retriever, Maxx has suffered from IBD since he was a puppy. Therapeutic diets, prebiotics, probiotics and antibiotics have been minimally helpful. Loperamide HCl (Imodium®), an over-the-counter (no prescription needed) medication is the only medication that I have found that returns his stools to normal firmness and frequency. Loperamide slows your dog’s colon emptying time which give its colon more time to extract water from intestinal contents. Maxx receives two 2 mg tablets hidden in his favorite treat three times a week. Others report success with Lomotil®, an entirely different medication. Consult your veterinarian for an appropriate dose size and dose frequency for your pet. Too much or too frequently can result in constipation and other side effects.

Antibiotics

Antibiotics

If a new diet alone does not solve your dog’s IBD issues, the second thing often added to your dog’s treatment plan, is an antibiotic – at least until the dog’s diarrhea subsides. IBD dogs that respond positively to antibiotics are sometimes called ARD dogs (antibiotic-responsive diarrhea). They tend to be the larger breeds. The chronic diarrheas of German shepherd dogs with IBD often respond positively to antibiotics.

The most common antibiotic that veterinarians prescribe for persistent diarrheas is metronidazole (Flagyl®). Although Flagyl® is an antibiotic that kills both bacteria and protozoa (like giardia), the drug seems to lessen diarrhea in ways that are not yet understood. Some believe that the drug has effects on the pet’s immune system. Metronidazole is the most horrible tasting medication on your veterinarian’s shelf. It tastes terrible if film-coated tablets or capsules are not swallowed whole, or the coatings contaminated with powder. With time cats and a lot of dogs learn to run when they see you coming with Flagyl®. But the drug is often effective if you can get it in them without a major struggle. Perhaps a drug compounding company can prepare it for you in a form acceptable to your dog.

Another antibiotic, tylosin (Tylan®), also sometimes helps in controlling IBD when it is added to your pet’s food. Others report success using oxytetracycline. A newer antibiotic, used with apparent success in treating IBD in humans, is rifaximin. In the United States it is quite expensive. I have no experience using this medication, but I know that it seemed to provide benefits to dogs when given experimentally.

Medications That Work Directly On Your Pet’s Immune System

Medications That Work Directly On Your Pet’s Immune System

The majority of dogs with IBD do not need long-term administration of powerful drugs that lessen gastrointestinal inflammation by “turning down the volume” of the dog’s immune system. With the exception of budesonide, when these corticosteroid drugs exert their anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive effect, they do so throughout your dog’s entire body. So, any dog on any of these medications needs to be closely monitored. Weight gain, increased thirst and fluid retention are the easiest signs to monitor, but your vet will rightly want to monitor considerably more than that.

The most common drug in this group that veterinarians give to IBD dogs is probably oral prednisone. When that drug or similar medications are first given, the dose is usually daily or even twice a day. After a time, your veterinarian is likely to lengthen the periods between doses to see how little of the drug can be effective in satisfactorily controlling your dog’s symptoms. Steroids should always be given at the smallest effective, and most infrequent dose. The goal is always to reach a point where the drug becomes unnecessary – but in some pets that can be unattainable.

Prednisone is a corticosteroid. When a dog improves on a drug in this class, some veterinarians and physicians call it a “steroid-responsive IBD (SRD). All drugs in this class are very effective in reducing inflammation. As I mentioned, all corticosteroids can produce a number of serious side effects. Those include weight gain, negative liver changes, increased thirst, increased susceptibility to diabetes, increased susceptibility to infections and increased susceptibility to cataracts and corneal ulcers.

Budesonide

Budesonide is the most common corticosteroid given to humans who suffer from IBD. It was designed to act locally in the intestine, be less absorbed into the body and so less inclined to produce systemic (body wide) side effects. Although that is true theoretically, it is not always the case. So dogs taking budesonide still need to be carefully monitored for the possible corticosteroid-related side effects. In the United States, budesonide is also quite expensive.

Sulfasalazine

Although sulfasalazine is metabolized by bacteria in your dog’s colon into a sulfa antibiotic, it is not given for its antibacterial properties. A portion of the original drug (mesalazine) inhibits inflammation. Because the drug needs to reach your dog’s colon to produce mesalazine, it is not likely to be effective when your dog’s IBD inflammation extends to or exists only higher up in its intestines than its colon. Sulfasalazine occasionally affected the glands of the eyes that produce tears causing a permanent problem called dry eye (keratoconjunctivitis sicca) (KCS).

Other Drugs

There are cases of severe IBD that do not respond adequately to the drugs I have mentioned. When humans face that issue, their physicians now have monoclonal antibody biological drugs (mAb s) that block intestinal inflammation. These are drugs like Remicade®, Humira® and Cimzia®. These Monoclonal antibody products are designed to block the production of the underlying drivers of inflammation – inflammatory cytokines. Bioengineered monoclonal antibodies are constructed to mimic natural human antibodies. So, the human immune system accepts them as being normal human proteins. If you were to attempt to give any of those medications to your dog, your dog’s immune system would consider them dangerous foreign proteins and quickly destroy them.

The only monoclonal antibody currently approved for use in dogs has been “caninized”. That is, constructed to be accepted by a dog’s immune system. It is Cytopoint® and it is marketed for canine allergic skin disease. However, Cytopoint® blocks an inflammatory cytokine (IL31) that has also been implicated as being involved in IBD. I know of two clients dogs that suffered from both inflammatory bowel disease and canine skin allergies (atopic dermatitis). When her vet switched the dog from Apoquel® to Cytopoint® not only did its skin improve, its IBD resolved as well. Cytopoint® requires periodic injections. It is not a permanent cure for anything. If your IBD dog has had a similar positive experience or if it failed to improve its IBD signs while on Cytopoint®, I would appreciate knowing. You can read about those two cases here.

In cases where the traditional IBD drugs I mentioned fail, the only options I can suggest are to accept that your dog’s problem is incurable and adapt both your lifestyles to dealing with that or resort to chemotherapy. There are plenty of chemo/immunosuppressive drugs that decrease intestinal inflammation. The problem is, at what cost to your dog’s general health? Some of those drugs – occasionally administered to dogs with IBD – are cyclosporin, cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan®), azathioprine (Imuran®) and chlorambucil (Leukeran®). If I were to go that road, my choice would probably be cyclosporin/Atopica®. Other dog owners in their desperation might resort to treatments that are not evidence-based : stem cells, elemental diets, core supplements, etc. – all complete with glowing testimonials. If I thought that any of them were worth pursuing I would have already told you so.

Protein Loosing Enteropathy (PLE) – The Most Severe Form of IBD

When your dog’s intestines are injured by the inflammation that accompanies IBD, occasionally enough damage occurs that the dog’s body can no longer keep blood constituents from leaking out through the intestinal wall and being expelled from the body. One of the first to be lost is albumin, the most prevalent protein in normal blood. Your vet will most certainly glance at your dog’s total protein (TP) levels as reported by their in-office analyzer or a central lab. Lower than normal blood protein is never a good sign when dealing with IBD.

But low blood protein with diarrhea is not always a sign of IBD. It can also occur when a dog suffers from conditions call intestinal lymphangiectasia or from intestinal lymphoma cancer as well. Severe dietary protein deprivation (malnutrition) will also cause low blood protein levels. Your vet will also want to rule out that the albumen blood protein is not being lost through your dog’s kidneys. Damaged kidneys leak blood albumin into the pet’s urine. (read here) Your veterinarian will have a look at your dog’s liver test results. It takes a healthy liver to manufacture most of your dog’s blood albumen. Your veterinarian might find it appropriate to screen your dog for Addison’s disease (hypoadrenocorticism), since signs of that disease and protein losing enteropathy (PLE) can overlap.

A clinical sign of PLE (besides those of IBD) that occasionally occurs is a bloated abdomen (ascites). Ascites sometimes causes difficulty breathing because it can restrict the movement of your pet’s diaphragm. Some dogs with PLE experience muscle tremors, facial twitching and even seizures because other blood elements (e.g. calcium and magnesium) can leak out through the intestine with the protein as well. Vitamin D3 levels and cholesterol levels are also sometimes low in those dogs. For reasons unknown, dogs with PLE also seem more susceptible to blood clots (hypercoagulable blood).

Protein leakage in protein losing enteropathy can be through small ulcerated areas of your dog’s intestine. But it can also be between the living cells that constitute the intestines inner lining. Blood must be very close to these inner lining cell to receive the food nutrients that are allowed to pass. Yet, these cells must prevent (hold back) important blood constituents from going in the other direction. That is where the concept of tight junctions between the barrier cells comes in to play. In one study in dogs, cells of an IBD-activated immune system (the macrophages) were found to liberate an inflammatory cytokine (IL-1b) which, in turn decreased the formation of one of the major “glues” (occludin) that form these tight junctions in the dog’s intestines to hold back blood protein. Read that study here. If their theory is correct, it might partially explain why some dogs with IBD develop protein loosing enteropathy. But there are other theories. (read here)

Might A Microbiota/Fecal transplantation (FMT) Be Helpful To My Dog?

Perhaps.

We know that dogs with IBD have lost much of the rich bacterial flora that should be present inside them. What we do not know is whether that is the cause or the result of IBD. We also know that at least in some dogs, their intestines are now inhospitable to bacterial diversity. So, it is unclear if re-seeding the dog will lead to lasting improvement. It might be, if your dog had previously been given antibiotics that destroyed important species of its “good” bacteria. In humans, some find their way back on their own with time, a few may not. Or if a food-responsive case of IBD was now in remission. And it might be worthwhile doing anyway – even if the benefits were only transitory. In humans, fecal transplants are sometimes though to be helpful in reducing IBD symptoms. The technique is simple and economical with little or no downside. So, it might be something you might consider for your dog.

The pastes and jells sold commercially as probiotics for dogs are not a source of rich mixed populations of bacteria. At the most, they contain just a few. The best source of a rich diverse bacterial flora is another healthy dog. I would not fear a mechanical transplant to your pet from a well-screened donor dog.

Many do not realize how resilient most of these health bacteria really are. Many of these organisms – often thought to be fragile and unable to survive outside the intestine – produce spores that are resistant to drying, oxygen and the environment. (read here & here) So it may not be necessary for you or your veterinarian to actually mechanically move feces from one dog to another (when that is done, it is generally by high enema). Your pet’s close contact for a week or two with a healthy dog, a shared water bowl, shared food dish and toys might be all that is required.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.