Ron Hines DVM PhD

See What Normal Blood & Urine Values Are

See What Normal Blood & Urine Values Are

Causes Of Most Abnormal Blood & Urine Tests

Causes Of Most Abnormal Blood & Urine Tests

Your Dog And Cat’s White Blood Cell Count = WBC, Leukocyte Count, Leukogram

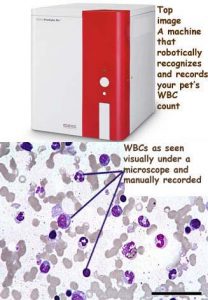

The white blood cell count or WBC is a part of your pet’s CBC or complete blood cell count. When oxygen-carrying red blood cells (RBCs) and thrombocytes/ aka platelets that help form blood clots are part of the report it is a CBC, when they are not included it is a WBC.

The job of your dog or cat’s white blood cells is to defend its body. These cells (WBCs=leukocytes) are the foot soldiers of the immune system. They appear white (white=leuko) when they form a thin upper layer on a centrifuged sample of your pet’s blood – hence their name.

When there are not enough of them (leukopenia) your pet is at risk of infection. When there are too many of them (leukocytosis), your cat or dog is in an active battle against some perceived or imaginary foreign invader.

There are five basic types of white blood cells: neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, lymphocytes and monocytes. Each has a different job. Read about them individually through their name links.

All WBCs, except the lymphocytes, originate in your dog or cat’s bone marrow. All except the lymphocyte take their names from their appearance when observed on a dye-stained microscope slide.

When your veterinarian orders or runs an in-house white blood cell count, it is generally as part of a CBC (=complete blood cell count) and along with a blood chemistry panel. The report your veterinarian receives will give your pet’s white blood cell total numbers (in number of WBCs/microliter [µL] of blood = Cells x 10 3 /cubic mm of blood = /µL). Mature (segmented/= “segs”) and immature (bands/band cells) neutrophils are reported separately.

Besides giving the total number of each of the five cell types (=the absolute count) it will give the percentage of the total white blood cells that each cell type makes up (the differential count). All of those values help your veterinarian make sense of the data. They can give your vet important clues as to the nature of your pet’s illness or help give it a clean bill of health during periodic check-ups.

Reasons Why Your Dog And Cat’s White Blood Cell Count Might Be High (leukocytosis):

Any form of inflammation, infection or tissue destruction that releases signaling chemicals (inflammatory cytokines, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, C-reactive protein. etc.) into your pet’s blood stream will cause high white blood cell counts if your pet’s bone marrow is healthy. Some forms of cancer also have this effect. Generally, the more severe an infection or underlying disease is, the higher the WBC count will initially be.

Toxins that accumulate in organ failure (such as kidney or liver disease) can also increase your pet’s white blood cell count. So can toxic products that your pet consumes (although that is usually secondary to tissue damaged caused elsewhere). Late in these situations, WBC numbers can actually be low due to bone marrow exhaustion. In humans, the elderly tend to be less capable of generating high WBC numbers. Whether that is the case in dogs and cats is unknown.

A very common problem when pets come to animal hospitals is their fear, apprehension and excitement; although some pets generate those feeling much more than others. Being in an agitated, stressed and excited state, releases two compounds that can increase your pet’s WBC count. Both are released by your pet’s adrenal glands. The first is epinephrine (adrenaline). That chemical increases your pet’s heart and respiratory rate and dilates its pupils (the adrenaline rush). Another effect of epinephrine is an increased WBC count (= leukocytosis) as white blood cells that once clung to the walls of blood vessels (the marginal pool) detach and move into circulation while additional WBCs stored in your dog or cat’s spleen are squeezed out into the blood stream. This happens fast – within minutes. In dogs, it is usually the more mature neutrophils (“segs”) that have increased in number. In cats, it may be lymphocytes as well. Heavy exercise can have a similar effect.

A second effect of stress takes a bit longer to develop. Your dog or cat’s adrenal glands will also increase their corticosteroid (cortisone) production when the pet is under stress. The same thing happens when other corticosteroids are given to your pet in pill or injectable form to treat a health issue. When that situation exits, the number of lymphocytes in your pet’s blood tend to go down while the number of neutrophils tends to go up. Again, it is the mature neutrophils (“segs”) that tend to rise the most. Veterinarians refer to both these phenomena as a stress leukogram. Eosinophils and monocytes can rise a bit in this situation as well, but rarely as dramatically.

Folks tend to associate viral diseases with low leukocyte counts (= leukopenia). But when secondary infections like bacterial pneumonia occur late in viral distemper infections or the intestines become damaged from canine parvovirus, white blood cell numbers can actually go up. Viral FIP in cats can cause a similar rise in neutrophil numbers. In those cats, lymphocyte numbers generally go down. Those levels often persist until the pet either runs out of reserve WBCs or gets better.

Very high white blood cell counts can also occur due to bone marrow changes (hyperplasia) or bone marrow cancer. In those cases, the WBCs liberated into the blood stream tend to be abnormal in appearance. That is when the trained eye of a veterinary clinical pathologist is so helpful. When those tumors are of the cell line (stem cells) that produce neutrophils, it will be only the neutrophil numbers that are high. But any one of the 5 types can be affected and that proliferation can limit the bone marrow’s ability to produce other blood cells.

Young dogs and cats (before their first heat) tend to have higher WBC counts than older adults. Dogs brought to the vet in labor also tend to have elevated WBC counts. I do not know if that is due to the stress of labor, the fear associated with hospitalization, changes in their hormone levels or all of those factors combined.

Reasons Why Your Pet’s White Blood Cell Count Could Be Low (leukopenia):

The bone marrow of dogs and cats has a limited (finite) ability to produce white blood cells at an increased rate. Prolonged diseases of all kinds can exhaust that ability. So, after a sudden overwhelming infection or a ceaseless demand for extra WBCs over time, your pet’s bone marrow can simply run out of new WBCs to release into the pet’s blood stream. That is particularly true of neutrophils (= neutropenia).

I already mentioned that viral infections often cause total white blood cell numbers to go down. A moderate drop in number is often seen in coronavirus infection of dogs and infectious canine hepatitis. The drop is much more severe early in parvovirus infection of dogs and panleukopenia in cats. WBC counts are often low in FIV-positive cats as well. Feline leukemia virus positive cats are not as predictable in the way their WBC numbers respond.

Space-occupying tumors of your pet’s bone marrow (stem cell myelomas) can squeeze out the cells that normally produce other WBC, thrombocyte and RBC lines. As I mentioned earlier, those tumors also have the potential to release enormous numbers of defective WBCs into the pet’s circulation causing very high WBC numbers. Any tumor that metastasizes to the bone can probably do similar things. But it is difficult to sort things out because many of the chemotherapy drugs used to treat cancer also depress the production of WBCs.

Certain autoimmune diseases (primarily of dogs) cause pets to destroy their own WBCs (immune-mediated neutropenia). When that sort of problem is suspected in a dog, Ehrlichia infection needs to be ruled out since the symptoms can be similar.

Other medications that are known to occasionally cause low WBC numbers are: methimazole given to cats for hyperthyroidism (in 4-10% of cats), certain antibiotics (e.g. trimethoprim-sulfa), medications to combat fever (e.g. dipyrone & aspirin best avoided).

Clomipramine (Clomicalm®), given to dogs for anxiety and panic, has caused low WBC counts when given to humans for the same sort of problems. I am uncertain if that effects occurs in pets.

Estrogens given as the infamous “mismating” shot to female dogs also has that potential. (read here)

A genetic disease of gray collies called cyclic hematopoiesis has the potential to cause WBC counts to drop about every 11-14 days. A similar condition sometimes occurs in blue-smoke-color Persian cats (Chediak-Higashi syndrome).

Greyhounds (and possibly other sight hounds and Belgian Tervuren) tend to have lower WBC counts than is normal in other breeds (3.5-6.5 vs 6-17). So one needs to look for other signs of illness when interpreting blood data from those breeds.

Complementary Tests:

Begin with evaluation of the dog or cat’s CBC / WBC and blood chemistry values. With that data in hand and your veterinarian’s physical examination complete, the possible tests that your vet might think appropriate for your dog or cat are too many for me to list. When one or two test results are borderline – and if the pet appears healthy in other respects – it is usually OK to wait a week or two and re-run the WBC count before pursuing other diagnostic test, medications or options. Remember that giving antibiotics for false alarms make it more likely that they will be ineffective when a real fire occurs.