Knee Injuries in Your Dog ACL Anterior Cruciate Ligament Problems -Their Repair And Treatment

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Neutering too young is a risk factor for cruciate ligament problems

Neutering too young is a risk factor for cruciate ligament problems

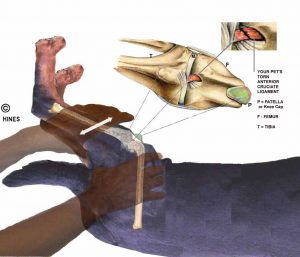

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) and the Cranial Cruciate Ligament (CCL) are the same thing. Our knee is our pet’s stifle. Physicians describe the ligament as “anterior” because it is toward our front. Veterinarians describe it as “cranial” because it is toward the pet’s head.

What Are The Cruciate Ligaments, And What Happened To Them In My Dog?

Your dog’s knee is also called its stifle. I circled that joint here

As you can see in the skeletal image above, your pet’s stifle is the joint that bridges the upper and lower leg bones, the femur and tibia. Your pet’s stifle is an amazingly complex joint. To add stability to the joint, Nature has provided some very strong ligaments. Two of these are attached in a crosswise fashion, hence the names, anterior and posterior cruciates or “cross” ligaments. These ligaments act together with two outer bands of fibrous ligament, the lateral collateral ligaments, and the kneecap to maintain your pet’s knee stability through a wide range of motion.

A small group of dogs suffers torn cruciates as a true sports injury. These are the dogs that test the limits of body endurance through over-exertion, agility trials, dock jumping, surfboarding, and the like.

But veterinarians see cruciate ligament injury much more frequently in overweight, neutered, middle-aged dogs. Veterinarians used to think of cruciate tears as a relatively simple and straightforward problem – the dog made a sudden incorrect move, the ligament tore. But recent research shows that cruciate problems are anything but simple and straightforward in their cause and treatment.

For instance:

Research shows that dogs over 4 years old that are spayed or neutered are considerably more likely to suffer cruciate tears than dogs that remain sexually intact. (read here)

We used to think that cruciate problems appeared suddenly – after a sudden twisting movement or due to jumping up or out of an elevated location. But we now know that this problem has usually been brewing for some time. There is even some evidence that these ligaments sometimes tear after your pet’s joint becomes inflamed (lymphoplasmacytic synovitis) – rather than becoming inflamed because of a torn ligament as we had once supposed. (read here & here)

Whatever the cause or causes, something more than a simple accident is usually occurring because it is common for the pet’s second knee to go out sometime after the first.

Another group of dogs that suffer from this disease are those receiving corticosteroid medications for long periods. It is uncertain if these pets develop the problem because they gain weight or because corticosteroids decrease ligamental strength (both are known to occur). A similar over-abundance of corticosteroids occur if your pet develops Cushing’s disease. Cushing’s disease also causes lax ligaments and weight gain.

I also believe that dogs today do not get as much exercise as they should. Activity strengthens joints, muscles, and ligaments. For instance, girls that do not engage in high levels of physical activity have joints that are less robust than those that do. (read here)

How Will My Veterinarian Diagnose A Cruciate Ligament Problem In My Dog?

Examination of a painful stifle (knee) in your pet is most accurate when it is done under anesthesia or heavy sedation. Besides being painful, the muscles of your pet’s joint will probably be in spasm, making diagnosis difficult or impossible in an un-anesthetized pet.

After relaxing the pet, most veterinarians will place one hand on the thigh to immobilize the femur and the other hand below the knee and attempt to move the tibia anteriorly and posteriorly as the white arrow indicates in the diagram I drew at the top of this page. A normal joint will not move in these directions because intact cruciate ligaments prevent it. Only in knees where the cruciate ligaments have snapped or stretched is this forward and backwards sliding motion possible. Some call this motion the “anterior drawer” effect. The term was taken from human medicine many years ago. (As performed on dogs or cats it is actually more similar to the Lachman Test which you can view here. As I mentioned, to give valid results, the test needs to be performed by your veterinarian while the pet is sedated. That is usually at the same time that x-rays of your dog’s stifle (knee) are taken.)

In old injuries to the knee, scarring may prevent some of this characteristic motion, but not the pain. In old injuries, the lateral collateral ligaments that stabilize the knee may be stretched and loose as well.

In most cases it’s the anterior (front), rather than posterior cruciate ligament that has torn. The affected knee might pop and click when it is manipulated – particularly when the injury has been present a while. Those older injured knees are occasionally a bit puffy with excess fluid. Sophisticated veterinary centers confirm cruciate tears in more sophisticated ways. When the dog is large enough, an arthroscope can be inserted into the joint to actually see if the cruciate ligament is torn and if the meniscal cartilage has been damaged.

X-rays will not detect damaged cruciate ligaments in your pet when they occur. But they will pick up later arthritic joint changes that develop in the unstable joint. Sometimes, cruciate ligament injury is mistaken for hip dysplasia. (read here) And some dogs actually do have both hip and knee issues at the same time. In rare instances, where both legs are affected simultaneously, torn cruciates might be mistaken for a spinal cord injury.

What Treatment Might Be Best For My Dog?

Veterinarians have the option to treat pets with cruciate ligament tears medically or surgically.

Conservative Medical Treatment

Publications keep veterinarians abreast of their current therapy options regarding cruciate ligament damage. The director of the Comparative and Integrative Pain Medicine Center at Colorado State Veterinary School, published a well-researched article on conservative treatment options for pets that have injured their cruciate ligaments.

If your dog’s optimum weighs is 55 pounds or less, I believe that conservative non-surgical treatment is often your best choice. Most of these lighter pets will improve with rest, restriction of strenuous exercise, hydrotherapy and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications to combat pain and inflammation. I believe that more than two-thirds of the dogs that weight under thirty pounds will be nearly normal in six months. If your dog is overweight, it is important that that be corrected. Read about weight control in your dog here. If your dog is neutered and shows signs of Cushing’s disease, a cortisol:creatinine screening test might be desirable as well. Be sure your dog’s toenails are maintained short.

Some veterinary hospitals have specialized tanks and whirlpools for hydrotherapy. If not, they will refer you to a center that does. Stretch/range-of-motion exercises seem to be quite helpful too. Other veterinary practices treat knee injuries with methods that have less documented benefits such as cryotherapy, laser therapy and neuromuscular electrical stimulation – treatments commonly used in human sports and rehabilitative medicine. (read here)

Orthotic knee braces are a more proven option for residual pain relief, rehabilitation, as an alternative to surgery or to aid in your dog’s post-surgical recovery. When knee braces have good design and good fit, they can be a great help to dogs with knee problems – with or without surgery. However, they only work well when they fit well (not too loose-not too tight) and when dogs do not destroy them in an attempt to get them off (bitter’s spray is of no help). Some dogs accept them readily and think nothing more about them. Others plot throughout the day on ways to get them off. Tight-fitting braces cut off circulation, irritate the skin and cause the dog to bear weight in ways that can make the situation worse. Loose fitting braces fall off and do not give adequate support to the knee. It is similar to wearing a set of shoes that are not your exact size or somebody else’s eyeglasses.

I am dubious about services that plan to mail your dog a brace based on x-rays, size or breed. The results will be like ordering a new suit without having the tailor measure you in person. Maybe you will be lucky, and it will fit; but maybe you won’t. Ideally, bring your dog to the orthotic specialist to be fitted. If that can’t be done, have a cast prepared of your dog’s leg and have the specialist use that as a mannequin to construct the brace. Be sure you know their re-fit, refund and return policy (preferably in writing) before you make a purchase. Off-the-shelf braces that only approximate your dog’s size are problematic. If they refer to the brace by a # or letter, it is most likely off-the-shelf.

Even in large breeds, lameness due to cruciate injuries can decrease in severity with conservative treatment and time. However, if instability of the knee remains, it will eventually lead to arthritis of the joint and reluctance to use the affected leg. It is not clear that that happens any less frequently subsequent to canine knee surgery. How soon those changes occur and how severe they might be is unpredictable.

Also, critical for long-term management of your pet, is returning it to its optimum body weight when it is overweight. Provide regular moderate exercise and increase your pet’s exertion level very gradually. Your dog does not understand what happened to its knee, and it may be inclined to overdo it if you let or encourage your dog to do so. Be sure to cut back the level of exercise at the first sign of knee discomfort. When a dog is pain-free, toenail wear should be equal on both rear legs. So should the approximate diameter of its thighs and calves.

Surgical Treatment For Torn Cruciate Ligaments

There are a large number of surgical techniques that are attempted to repair the knees of pets that have been destabilized by a torn cruciate ligament. I believe that the reason there are so many techniques is that no one has been very satisfied with the results of any of them. Some techniques insert devices that attempt to stabilize the knee and require opening the joint (intracapsular techniques). Others attempt to add strength to the structures surrounding the joint to compensate for the lack of stability the cruciate ligaments used to provide. These are called extracapsular techniques. Two techniques (TPLO, TTA) are based on the assumption that the knee can be rebuilt in a way that no longer requires central stabilization. That assumption is based on a theory that abnormal angles between the upper (femur) and lower (tibia) bones is the cause of cruciate ligament injury. That was pretty much disproved. (read here)

The problem with currently available surgical techniques is that they do not adequately restore stability to your dog’s joint nor quiet the ongoing synovitis (inflammation) going on within it. Without stability, the slick coatings of your dog’s femur and tibia remain inflamed. Arthritic bone growth advances into the joint space that was once covered by these slick, gliding surfaces. That eventually leads to pain and loss of mobility. When entirely different techniques, based on competing theories and explanations of what underlies cruciate ligament tears, ALL give about 85% limited improvement; one must wonder if it is not just time, the post-surgical scaring and tightening of the joint capsule, post-surgical rest, physiotherapy and rehabilitation that accounts for improvement when it does occur. (read here) It has been known for many years that disruption of tissue can have a therapeutic effect. The phenomenon is called prolotherapy. All the current surgical techniques used to treat cruciate ligament damage in dogs share elements of prolothrapy. I believe that when these knee surgeries are beneficial, prolotherapy-like effects account for much of the benefit.

These facts can be very hard for owners and veterinarians alike to accept. Particularly veterinarians who specialize in surgery. Owners desperately want a cure for the pet they love. So much so that, according to one source, they spent 1.32 billion dollar in 2003 attempting to help their pets through cruciate pain. (read here) In 2009, five times as many dogs underwent cruciate surgery in the US as people – even though people outnumber dogs nearly five to one. If anything, figures are even worse today.

One of the few scientifically conducted studies on the limited success rates of various surgical techniques used to treat cruciate ligament damage was conducted in 2005 at Iowa State University. It can be faulted when used as a final verdict on cruciate surgery because the pets involved had mescal cartilage damage as well as cruciate tears (not all cruciate cases do). But it is the only impartial study of its kind that I know of. (read here) Other techniques have been developed since then. Initial success rates for new techniques tend to be considerably better than what longer-term experience finds to actually be the case.

Here are some of the surgical techniques your dog may be offered:

LSS (lateral suture stabilization

The same 2005 study found that 14.9% of dogs undergoing this surgery returned to normal leg function – no greater than the number that would have recovered without surgery. In 40% some improvement was noticed.

ICS (intracapsular over-the-top stabilization surgery)

The same 2005 study found that 15% of dogs undergoing this surgery returned to normal leg function – also no greater than the number that

would have recovered without surgery. In 15% some improvement was noticed.

TPLO (tibial plateau leveling osteotomy surgery)

This technique changes the angle at which the tibial portion of the pet’s knee rides on the pet’s femur on the theory that a functional stifle can be obtained by redirection of forces. However, in a study of 150 dogs published in 2008, researchers found that there was no evidence that the pet’s TPA (tibia plateau angle) predicted the rupture of the second knee cruciate in dogs. That is, extremes in the angle this surgery corrects do not in themselves cause the cruciate ligament to rupture. (read here)

The 2005 study found that 10.9% of dogs undergoing TPLO surgery returned to normal leg function – no greater than the number that would have recovered without surgery. In 34% some improvement was noticed. An article in the November 2007 issue of Clinicians Brief confirmed that TPLO does not stop or reverse the progress of osteoarthritis in the knees of dogs with cruciate ligament tears.

The chairman of the Orthopedics Department at U. of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine has been quoted in 2006 as saying: “The TPLO doesn’t seem to have any great advantage over more conservative forms of treatment”. and, in another interview, as stating : “There are no evidence-based studies to show that the results are any better than traditional surgeries and the invasiveness & cost is much higher. The morbidity is also much higher & therefore at U of P – we do not do it”. (see here) (times change, some of their surgeons do TPLO now)

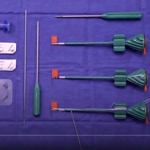

Tightrope (TR CCL) surgery procedure

This rather-recent procedure attempts to temporarily stabilize the pet’s loose stifle with a fiber tape. The theory presented is that permanent scaring of the pet’s joint capsule will eliminate or improve joint stability. Of all the surgical options, options like these that do not open the joint or saw bones are my favorites. Besides offering reasonable results it is so much less traumatic than TPLO. For that reason, I believe it is less likely to lead to post-surgical infections that occur in 2.5 to 15.8% of TPLO procedures. (read here) See how veterinarians perform the one version of the tightrope procedure here and here (if you did not view it in the links at the top of the page). Watch a veterinarian show you how the procedure is performed here.

A “white paper” from the manufacturer stated that 6-months outcomes are “as good or better than TPLO”. Considering the questionable results of TPLO, that was not much to brag about. But if you do decide that your pet must undergo knee surgery, I suggest an extracapsular technique similar to this one. Less damage is done within the joint, recovery is faster and results are as satisfactory as any. There is also much less risk of infection than when the joint is opened. Be sure that antibiotics are prescribed after surgery anyway. (read here)

TTA (tibial tuberosity advancement surgery)

This surgical method uses what I believe to be the same defective reasoning used to justify TPLO surgery. Its chief advantages are that it is a less-involved extra-capsular procedure when compared to TPLO, the Company says it causes less damage to the joint than TPLO, and it costs less to perform. (see here)

FHT (fibular head transposition surgery)

Research published in 1994 identified this once widely performed surgical procedure for torn cruciates in dogs as worthless. (read here) That it had such an extensive following among veterinary surgeons for quite some time emphasizes how difficult it is to accurately evaluate treatment success.

So, Why Is My Vet Recommending This Surgery?

You can read more about that at the end of this article. All veterinarians want to heal pets. Veterinarians in general practice know that they have no silver bullets to deal with cruciate ligament tears. So, they are likely to pass you along to a “specialist”, just as your general practice physician will do when he suspects a difficult case. There are many very good general-practice vets who truly believe these procedures work and want you to be aware of them. But there are also several problematic incentives for sending you to a veterinary surgeon rather than advising patience and physical therapy.

1) If your veterinarian advises patience, physical therapy and medical management of your pet’s knee, and it gets better, the outcome for your vet is neutral. But if the knee problem gets worse or does not return to full function (as well may occur), your vet might feel that he/she will get the blame. We live in a time when people are inclined to look for someone to blame when unfortunate things happen in their lives.

2) In many states in the USA, there can also be severe licensing and liability repercussions for your veterinarian if he/she does not refer you to a specialist or at least mention that that is an option.

3) Orthopedic surgeons – human and veterinary – feel the need to practice their specialty. If they were not enthusiastic about their craft, they would work in another fields. But this exuberance can lead to excesses. For example, commonly performed arthroscopic surgery for knee arthritis in humans is often of dubious value (read here) and many feel that surgical cruciate repair in people is often unnecessary and non-beneficial as well. (read here)

I am very proud of the free enterprise and entrepreneurship that exists in the veterinary profession in the United States. But making intelligent health choices for your dog will always pit pets and their owners against the never-changing nature of commerce and enterprise. When you visit a surgeon, you can expect surgery. When you visit the fresh fish counter, what are you likely to leave with?

How Can I Avoid Cruciate Ligament Problems In My Future Pets?

1) Do not neuter your dog at too young an age. Sex hormones are crucial to your pet for the development of health bones, tendons, joints and muscles. Let your female dog go through at least one heat cycle. Delay neutering your male dog (if you feel a need to do so at all) until it is an adult. Early age neutering also encourages obesity – a known risk factor for cruciate ligament and a myriad of other health problems. When the spay/neuter bus arrives, learn to just say No. A much more effective solution to the pet overpopulation problem is responsible pet ownership.

A much more effective solution to the pet overpopulation problem is responsible pet ownership.

2) Unless you plan to enter your dog in dog shows, purchase your dog from field trial or working lines rather than from show lines. Funny-shaped dog breeds are cute. They are trendy. They waddle about, they snort and they snore. But funny-shaped dog breeds also have funny shaped joints that place forces on their joints that Nature did not intend to happen.

3) Avoid puppies from larger-than-life parents – those from parents that exceed their traditional breed standard size. There tends to be a creep upward in the body size of many working breeds due to show judge pressure. The biggest in show and the smallest in show stand out and get the ribbons. This frequently leads to a variety of health problems including joint problems and a shorter life.

4) Do your best to not purchase from breeders that have had cruciate ligament problem in their history. There is already evidence that in Newfoundlands, a tendency to torn cruciates is genetically inherited. (read here) This has been confirmed in other dog joint problems as well. (read here)

5) Do not choose the largest or smallest pup in the litter. It has been my experience that health problems often occur at the extremes. Read about that here.

6) Slow the growth of your large-breed puppy. Feed your puppies 25% less than they would consume free-choice. This is known to suppress later hip dysplasia and elbow dysplasia problems in dogs and increase their life span. (read here) It might help avoid cruciate problems as well.

7) Keep your adult dog trim and lean. Do not overfeed it. Read about that here. Exercise your pet on a daily basis. Work pets into hard sports very gradually. Your dogs will do anything for you without regard for the well-being of its body or its safety. Do not ask your dog to do too much.

Are There Options When Knee Surgery Was Unsuccessful Or When Arthritis Within My Pet’s Knee Is Already Severe?

Yes, there is one. For a number of years, veterinary surgeons have attempted to place prosthetic (artificial) knees in dogs. These devices replace the entire natural joint and are patterned after the highly successful prosthetic knees used in people. As in humans, they are called TKRs (Total Knee Replacements). Much of this work was pioneered by a veterinary surgeon in Houston, TX ; but the procedure is now also performed at Ohio State University, The Veterinary College, U. of Minnesota, The Langford Veterinary Hospital at the University of Bristol in the UK, Helsinki, Finland as well as in Australia. Who and where surgical procedures are performed is always in flux.

The implant most commonly used is made of an upper, high-grade, metal alloy and a polyethylene plastic lower component. Currently, its manufacturer suggested that it be used in dogs weighing more than 26 lbs. (Biometrix)

The cost of the procedure and subsequent rehabilitation was said to be in the neighborhood of $7,500. I have no personal experience with this surgery – none of my clients have had the funds to have it performed. The procedure was still considered to be in the “clinical trial” stage, subject to modification as more long-term results became known. Repair of a single knee is usually sufficient for dogs to rise, get out and about and lead a pain-free life. But both knees have occasionally been replaced successfully.

Librela® (bedinvetmab) is a medication, designed by Zoetis to relieve the pain of joint arthritis in dogs. It is not curative. This injectable medication is already available in Europe. As 2022 nears its end, I do not believe that it is freely available in North America – other than perhaps in research studies. Check on that with the pain-control staff at the Veterinary School at the University of North Carolina. Please let me know their response. When similar monoclonal antibodies were tested in humans suffering from knee arthritis, the patients receiving it required knee replacements sooner than the control patients who did not receive the drug. The thought at the time was that because their knee pain was reduced, they over-used their knees.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.