Cushing’s Disease In Your Dog – Hyperadrenocorticism

What Happened And What You Need To Do

Ron Hines DVM PhD

My problem might be my adrenal glands. But more often it’s in my pituitary gland

My problem might be my adrenal glands. But more often it’s in my pituitary gland

See how my two glands work together

See how my two glands work together

Some dogs develop the opposite problem

Some dogs develop the opposite problem

Cushing’s Disease (aka hyperadrenocorticism) along with two others, hypothyroidism and diabetes, are the three most common hormone-related problems that veterinarians encounter in dogs. And of the three, Cushing’s Disease is probably the most complicated to diagnose and to treat.

Cushing’s Disease has been known for a very long time. Dr. Harvey Cushing first took note of its peculiar symptoms in a young woman he was treating in 1912. (read here) Veterinarians and physicians still call it Cushing’s Disease because its scientific name, hyperadrenocorticism, is such a tongue-twister to pronounce.

Veterinarians are diagnosing this disease in dogs considerably more frequently than they did not so many years ago. It is still unclear if this is because Cushing’s disease has become more common, or if we veterinarians are just looking for it more than we once did.

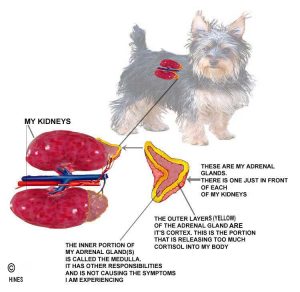

Understanding what is going on in your dog when it has Cushing’s disease requires understanding your pet’s very complex interlinked endocrine gland system. This system, no different from yours, delivers instruction messages, (in the form of hormones) via your pet’s blood stream to all parts of the body. The two endocrine glands that are the problem in Cushing’s disease (aka Cushing’s Syndrome = hypercortisolism = hyperadrenocorticism) are it’s pituitary gland, – the master gland of all glands – which sits at the base of the brain, and the pet’s two adrenal glands, which are located just ahead of its kidneys. I drew some diagrams at the top of this page in an attempt to show you a bit more about these wonder-glands of creation. I am going to try to keep the rest of this article as readable for ordinary pet owners as I can. There are only small differences between the functions of your own pituitary gland and your dog’s pituitary gland. If you prefer to read about the pituitary gland in “doctorspeak” instead of normal English, ask me to send you a copy of cushings-Sam2008.

Here is your dog’s basic problem: Its adrenal glands are producing too much of a certain hormone called cortisol. All the problems that you are seeing in your dog are the result of too much of this hormone circulating in its body.

There are two possible reasons your pet’s adrenal glands could be over-producing cortisol. The first would be a tumor located within one of the adrenal glands itself. However, a second, and more common cause would be a tumor located in your pet’s pituitary gland, located just below its brain. We think that about 85% of the cases of hyperadrenocorticism veterinarians see in dogs are due to tumors within the pituitary gland. This form is called pituitary-dependent Cushing’s (= PD, PDA or PDC form). In almost all the other 15%, the tumor is located in one or both of your dog’s adrenal glands. Those 15% are called the Adrenal-Dependent form (= AT, ADH form) of Cushing’s disease.

Cortisol hormone is a natural type of corticosteroid. As I mentioned, its production in your pet’s adrenal glands is under the control of its pituitary gland. Your pet’s pituitary gland is constantly monitoring blood levels of the cortisol your pet’s adrenal glands are manufacturing. When the pituitary gland decides it is necessary, it sends signals (in the form of ACTH) to your pet’s adrenals telling them to produce more cortisol. When a tumor or tumors form in the cells of the pituitary responsible for ACTH production (corticotropes) those tumorous out-of-control cells continuously release ACTH regardless of the cortisol level in your pet’s blood stream – sort of like a faulty thermostat running your air conditioning system that never shuts off.

These tumors, whether located in your pet’s pituitary or adrenal glands, are usually of a type called adenomas. They tend to be slow-growing and generally do not spread (metastasize) or threaten life in themselves. When these adenomas are located in the pet’s adrenal glands (only ~15% are), some produce hormones other than, or in addition to, cortisol in excess as well.

Cushing’s Syndrome is a disease of middle-aged and elderly pets. It can affect dogs as young as 5, but the average age at diagnosis is about 10–11 years. When the tumors are located in the pet’s adrenal glands, they tend to affect dogs a bit older than this (11-12 yrs). Adrenal tumors appear to be more common in the larger breeds and pituitary tumors more common in smaller breeds.

It can be helpful to understand some of the functions of cortisol in your dog’s body to understand the symptoms your pet is experiencing:

The Normal Roles Of Cortisol In Your Pet

Animals and people cannot live without a normal level of cortisol in their bodies. Not producing enough cortisol leads to Addison’s Disease. Without cortisol, one cannot adequately deal with stress. (read here)

Cortisol is important in mobilization of your pet’s body fat reserves for energy and in maintaining normal blood sugar (glucose) levels. It does this by increasing glucose formation in the pet’s liver.

Cortisol is essential to the function of your pet’s immune system too. However, when too much is present, it depresses immunity and increases susceptibility to infections. Sometimes chronic skin infections, thought to be the result of canine atopy, actually have hyperadrenocorticism disease as their underlying cause.

Cortisol suppresses inflammation throughout the body. That is why synthetic “similars” like prednisone and other corticosteroids reduce inflammation.

Cortisol is a basic regulator of many of the metabolic processes that occur in all the cells in your pet’s body.

In abnormally high levels, cortisol delays wound healing. That is why cortisone creams are a bad choice for wound and surgical incision aftercare.

At normal levels, cortisol supports muscle and ligament health; but at increased levels, it causes muscle, connective tissue and ligament weakness.

Cortisol is important in maintaining bone health, regulating calcium uptake and excretion as well as maintaining bone density. In abnormally high levels, cortisol slows the absorption of calcium from the diet.

In abnormally high amounts, cortisol thins a pet’s skin and increases hair shedding – that can lead to thin hair coats and baldness. It can even cause deposits of calcium to form within the skin. (see here)

Cortisol increases blood circulation and urine production within your pet’s kidneys (GFR or glomerular filtration rate). The abnormally high cortisol levels of Cushing’s disease often cause pets to drink and urinate excessively. That could be confused with kidney health issues.

Normal levels of cortisol are necessary for proper brain function. In humans, excess cortisol levels are associated with mood swings and loss of mental acuity. That probably occurs in some of our pets that have Cushing’s disease as well. If so, it might even be confused with the mental decline of elderly dogs (CDS), perhaps even for certain chronic liver problems (HE, MVD).

Your pet’s adrenal glands have two major layers. The inner one (medulla) plays little or no part in hyperadrenocorticism. The mid-portion of the outer layer, the adrenal cortex, produces all the cortisol (the zona fasciculata).

The amount of cortisol your pet’s adrenal glands produce is very unstable from minute to minute. It is constantly rising and falling depending on the pituitary gland’s assessment of the pet’s immediate needs. These pituitary ACTH “orders” are sent from the pituitary to the adrenals through the bloodstream. But since blood levels of cortisol constantly vary, a single blood sample taken from your pet is of little value in judging if it has Cushing’s disease. Somewhat more useful as a preliminary screening test is a urine cortisol to creatinine ratio that I mention farther along in this article.

What Signs Might I See If My Pet Has Cushing’s Disease?

Cushing’s is a disease that comes on very gradually – so you are quite likely to ignore the subtle early changes, or you might attribute them to something else. Your vet might do the same – it’s a common error we all make. Tests to confirm hyperadrenocorticism are expensive and time-consuming. Often they are reserved for dogs that just aren’t responding to our treatments for what we initially thought was the problem. This slow progress is due to the slow rate at which these tumors grow.

One of the most common early signs of Cushing’s disease is increased thirst and urination. Females pets are more likely to have accidents in the house and owners often tell me they have to fill their pet’s water bowl again and again or that their dog has begun crying to be let out to pee during the night. As I mentioned, sometimes the problem is mistaken for a urinary tract infection, kidney issues or the beginnings of senility.

Another common symptom is weight gain. Increased cortisol levels increase the pet’s appetite as well as its tendency to retain fluids. It also causes the pet’s liver to grow larger. This, plus cortisol’s relaxation of the pet’s abdominal ligaments, often leads to a pot-bellied appearance. At the same time, muscle shrinkage leads to spindly legs. All this makes it harder for your pet to get about, jump up on the bed, and climb stairs. You might mistakenly think the problem was arthritis. (read here) You might also mistake the panting and shortness of breath brought on by muscle weakness for a heart problem. That is not to say that all those things could not co-exist in a dog with Cushing’s disease.

As I mentioned earlier, many of these pets have poor or sparse hair coats due to skin changes caused by the excess of cortisol hormone – particularly on their trunk and flanks. A key clue that hair loss or thinning might be occurring due to hyperadrenocorticism is its symmetrical distribution (the same on both sides of the body) and does not have the typical rump distribution of a flea problem.

Cortisol’s effect on your pet’s immune system may make your pet more susceptible to skin, ear and urinary tract infections. Even some of the cases of demodectic mange that occur in non-juvenile dogs probably have the immunosuppressive effect of Cushing’s disease as their underlying cause. (read here)

Many pets with Cushing’s disease are just not themselves. They have low-energy levels and lack the zest for life that they once had. A similar effect occurs in humans with this disease. Pets with Cushing’s disease may also be more susceptible to blood clots. (read here)

Hypertension (high blood pressure) in older dogs could be associated with hyperadrenocorticism – although high BP in dogs has many other causes. Cushing’s disease is known to be one of them in humans.

Please remember that many diseases of mature dogs that do not have Cushing’s disease, produce all or some of the symptoms I just listed and that it is very unlikely that your pet will exhibit all the signs I have listed even when Cushing’s is its underlying problem. So let it be your veterinarian who makes the decision as to what your pet’s underlying health issue really is.

What Might Make My Veterinarian Suspicious That My Pet Has Cushing’s Disease?

Besides the signs I just mentioned that you might notice at home, your veterinarian might notice other things on a routine examination that would bring Cushing’s disease to mind as a possible explanation :

Your vet might palpate (feel) an enlarged liver in your pet’s abdomen or be perplexed as to why previously treated infections have returned.

If you presented your dog to the vet because of a poor, thin hair coat, finding no evidence of skin parasites, bacterial or fungal infections to account for it might bring underlying endocrine gland problems like hyperadrenocorticism to her/his mind. Particularly if the itching was minor or nonexistent.

But it is the results of routine laboratory tests that vets run that would be most likely to ring alarms.

Many of these pets were brought in for urinary problems or peeing in the house. When the vet examines the urine of mature pets, he/she might wonder if Cushing’s disease might explain why the urine is so dilute in the absence of evidence of infection, kidney disease or diabetes.

In such a situation – when only vague symptoms are reported by you – your vet will probably suggest they send off some common blood counts and blood chemistry determinations or run them in house.

When those test results come back, a very common finding in “cushingoid” dogs is an elevated blood alkaline phosphatase (aka ALP, Alk Phos) level.

Liver enzymes (including ALT) might also be moderated elevated due to the strain this disease is placing on the pet’s liver. Cholesterol is often high as well.

A normal or low BUN and Creatinine level eliminates most kidney problems as a cause for your pet’s excessive thirst and, if their blood glucose level is normal, that eliminates the possibility of diabetes as well. (But it is not that unusual for pets to have Cushing’s, diabetes and other health problems going on at the same time!

It is common for dogs with Cushing’s disease to have an increased number of neutrophils in their blood as well as a lowered level of thyroid hormone (T-4). Their blood sugar level may be moderately increased as well if they are in a diabetic or pre-diabetic state. (You can go here to see what the normal blood values should be in your pet).

If your veterinarian runs x-rays, she/he might confirm that an enlarged liver is the cause of your pet’s increased girth (width) and – on rare occasion – calcium deposits might be seen in locations where they should not be (skin, kidneys, adrenals, etc.).

But again, none of the finding I listed are – in themselves – enough to make a definite diagnosis of Cushing’s disease. They are all common findings in many of the diseases that adult dogs suffer from.

What More Specific Tests Will My Veterinarian Want To Run To Be Sure?

So, your veterinarian will have to perform more specific, more complicated (and more costly) tests to decide if it is really hyperadrenocorticism that underlies your pet’s health problems. It is not an easy task or something that can be done quickly, and it usually takes two or more different tests for your veterinarian to be reasonably sure. Sometimes the results are cliffhangers – numbers sitting on the fence that that could go either way. As frustrating as that is to dog owners, repeating the tests might be required. It is never a fun job when your vet has the job of telling you that.

The Most Common Screening Tests For Cushing’s Disease

None of these screening tests are perfect and much controversy revolves around interpretation of their results. A pet’s endocrine system is in constant flux and most of the tests are only short snapshots in time. There are probably also genetic variations in how pets respond to compounds used in these tests and to elevated cortisol itself. Once your veterinarian is suspicious that Cushing’s might be the problem, the next step is to use one or more of these tests to confirm the diagnosis and, when possible, to distinguish a pituitary-dependent-problem (=PA, PDH) from adrenal-dependent-problem (=ADH) hyperadrenocorticism.

Urine Cortisol:creatinine Ratio

The urine cortisol:creatinine ratio (UC:Cr) test is the simplest, least expensive test to rule out, or rule in the possibility of hyperadrenocorticism disease in dogs. Dogs with normal UC:Cr ratios are unlikely to have Cushing’s disease. Those with abnormally high values need further testing because dogs with abnormal UC:Cr values do not all have Cushing’s disease.

Cortisol is continuously being lost into your pet’s urine. How much is present in a given amount of urine at any single time, depends on how dilute or concentrated your pet’s urine is, as well as the amount of cortisol in your pet’s blood. But creatinine levels in your pet’s blood remain fairly constant and are therefore at more stable levels in your dog’s urine as well (urine creatinine). So by measuring how much urine cortisol is present in relation to how much creatinine is present, veterinarians eliminate the natural variability of urine concentration as a factor, and get an indication as to how much cortisol was present in your pet’s blood stream when that particular urine was formed. Whether your dog drank a lot and produced dilute urine or didn’t drink and produced a concentrated urine is no longer a factor.

Urine for this test should be collected at home in the early morning (although a few vets still prefer a mixed, 24-hour sample). Do not bring your pet to the animal hospital – collect the urine at home. The stress of a car ride can be sufficient to alter the results in anxious pets. If your pet is emotional, let it calm down for a few days after its last vet visit before you collect the sample.

Your veterinarian will send your pet’s urine sample to a national testing laboratory. If the UC:Cr value is reported back as normal, your pet probably does not have Cushing’s disease. But only one dog in 4 or 5 that have an abnormally high (= positive) value actually do have Cushing’s disease. That is because gastrointestinal, urinary tract, liver and heart diseases – as well as simple stress can also make a pet’s UC:Cr value go up.

Low Dose Dexamethasone Suppression Test = (LDDST)

If your pet’s Urine cortisol:creatinine test result was abnormal or suspicious, this second test might be your veterinarian’s choice. For this test, your pet will have to spend the entire day at the animal hospital.

Dexamethasone is a synthetic compound similar to your pet’s own natural cortisol. When it is injected, your pet’s pituitary gland should mistake it for cortisol and inform the pet’s adrenal glands (through decreased ACTH release) that no more cortisol needs to be produced at the moment. In normal dogs, this causes a drop in their natural blood cortisol levels. If the level of blood cortisol remains high in your pet after the dexamethasone is given, one of two things are happening: Either, your pet’s pituitary gland has a pituitary tumor that continues to produce ACTH, or your pet has an adrenal tumor that continues to produce cortisol. Tumors pay no or little attention to messenger chemicals like ACTH.

The laboratory that receives your pet’s blood samples can tell the difference between the pet’s own cortisol and the dexamethasone that was given and will report back if the natural cortisol level dropped normally after the injection, by how much and for how long.

This test will detect most of the pets that have Cushing’s disease. However, certain medications (phenobarbital, phenytoin, spironolactone, tetracycline and perhaps others) can cause this test to fail. (read here) Also, some pituitary tumors retain some sensitivity to dexamethasone, which can also trick the test.

Some veterinarians rely on the 4-hour LDDS test sample to tell if the tumor is in the pituitary gland (PDH, PA) or adrenal gland (ADH, AT) (The odds are in their favor because about 85% of these tumors are in the pituitary) Others insist on running the High Dose Dexamethasone Suppression test (HDDS) to more positively locate the tumor. I generally let the clinical chemists at the lab I use (Antech Diagnostics) make that call because I trust their judgment. They are running these tests, day in and day out, and they have top-notch veterinary consultants specializing in endocrinology to assist in their decisions when required.

Opinions vary as to the accuracy of this test. Some veterinarians feel it gives too many false-positives and is not as accurate as the ACTH stimulation test. Others put great faith in its results. If there is any doubt in you or your veterinarian’s mind as to the significance of the results, or if your pet fails to benefit later from its medications, have them run an ACTH stimulation test as well. Test with “cliffhanger” results need to be repeated. I know these tests are expensive and a hassle, but Cushing’s medications can be toxic, and your vet will not want your pet taking them without a confirmed need.

ACTH Stimulation Test (= cosyntropin, tetracosactide or Synacthen test)

I mentioned that ACTH is the hormone that your pet’s pituitary gland normally releases lands to produce cortisol. If your veterinarian injects a synthetic form of ACTH (Cosyntropin, Cortrosyn) into your pet to stimulate the pet’s adrenal gal adrenal glands will respond by producing additional amounts of cortisol. But dogs with Cushing’s disease respond by producing even more (an exaggerated amount) than a normal pituitary/adrenal system would (normal<18 μg/dl, gray zone 18 – 22 μg/dl, Cushing’s >22 μg/dl). Read about the ACTH test here.

This test is not fool-proof either. There are a few non-adrenal diseases that can cause an abnormally high ACTH test results. Also, the ACTH test is more accurate in identifying dogs with pituitary tumors than those with tumors of the adrenal gland. When the test result is not clear-cut, your vet might suggest repeating it; or he/she might ask that the lab determine the levels of some similar hormones that may have shown a more dramatic spikes after the injection (e.g. progesterone, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, androstenedione).

High Dose Dexamethasone Suppression Test

Vets usually suggest this test when they already know that your pet has Cushing’s disease, but do not yet know whether the tumor is in the pet’s pituitary gland or its adrenal gland. It is performed similarly to the LDDS test – but a larger amount of dexamethasone is given.

If the tumor is in the adrenal glands, blood cortisol levels will not drop after the injection because the tumors have broken loose from the control of pituitary ACTH. If the tumor is in the pituitary gland, in theory, high doses of dexamethasone should suppress ACTH production and lower blood cortisol. Unfortunately, this theory does not hold up as well in practice as we would like. It appears that 20-30% of pituitary tumors fail to suppress the body’s ACTH in response to the dexamethasone – tumors come in endless variation.

Abdominal Ultrasound Imaging

In the 15% or so of dogs whose Cushing’s disease is due to an adrenal tumor, an ultrasound examination of your pet’s abdomen might detect the tumor(s). It is probably worth doing, but it misses quite a few adrenal gland tumors. Some tumors are too small to see. If one adrenal gland is larger than the other it might indicate a tumor was present in the larger one. However, tumors occasionally occur in both adrenal glands causing them to still be the same size and other non-tumor adrenal gland changes (adrenocortical nodular hyperplasia) can be mistaken for tumors. So, the veterinarian who performs this examination must be quite skilled in visualizing these difficult-to-see organs. Tumors of the right adrenal are considerably harder to see than tumors of the left.

Ultrasound examination is a painless procedure. Although it is not always successful, when it is, it is very helpful in distinguishing between the pituitary (PDH, PA) and the adrenal (AT, ADH) forms of Cushing’s disease. So, when it locates a functional adrenal tumor, it is a real help to your veterinarian in developing the best treatment plan for your pet. Adrenal gland tumors can often be removed.

The presence of an adrenal lump is, in itself, not sufficient to warrant surgery. Dexamethasone suppression and ACTH stimulation tests must also support the diagnosis of an adrenal tumor that is actually producing cortisol. Some of them don’t. (read here)

Other Forms Of Imaging

MRIs, and Cat Scan studies can sometimes also locate tumors in the adrenal gland when other test results are inconclusive. Occasionally, they detect calcified lesions within tumorous adrenal glands or liver enlargement as well – both sometimes occur in hyperadrenocorticism.

These techniques can also be used to examine your pet’s pituitary gland. However, only very large pituitary tumors are likely to be discovered in that way – pituitary tumors in most Cushing’s dogs are too small. However, if a tumor can be seen, and it is quite large (a “macrotumor”) it might indicate that the tumor has, or soon will, press on other portions of the pet’s brain. These tumors have been removed –. However, the surgery is delicate, expensive and risky. Some of the pituitary gland’s other vital processes will likely be destroyed in the surgical process. It is not a procedure I recommend to my clients – even though I performed it many years ago. If brain function is already compromised and euthanasia is the only other option, I do mention the surgical option to them.

Why Is Cushing’s Disease Such A Tough Problem For My Veterinarian To Handle?

Besides responding to your pet’s ever-changing needs for cortisol, the pituitary gland of all animals is known to produce signaling hormones in rhythms and cycles. Its processes ebb and flow like the tides. Some of these changes occur on a daily basis, some monthly, some annually or at even longer intervals. These are called biological rhythms Melatonin plays an important role in many of these processes.

There are no studies in dogs that I know of ; but in humans at least, some cases of pituitary-based Cushing’s disease do cycle. (read here)

So, Cushing’s tests that might be negative at one point could conceivably be positive at another and vice versa, and drug doses that were adequate at one point could be too small or too large at another point. It can be quite frustrating – like shooting at a moving target.

Another point of consternation (worry) is the potential toxicity of the two mainline drugs used to treat Cushing’s disease and the common ineffectiveness of the less-toxic ones. The high cost of repeated sophisticated testing is also an important decision factor for most pet owners. It is one that veterinarians like me dislike having to discuss.

Do I really Have To Have All These Tests Run?

If a low dose dexamethasone test result is strongly suggestive of hyperadrenocorticism (and your pet is ill), many vets find it acceptable to place your pet on appropriate medications and see how it does – we already know from the statistics that about 85% of these dogs have a tumor in their pituitary gland. It will depend on the philosophy of the veterinarian you use.

Here is the risk in doing that: If your pet is one of the other 15% that have the tumor in their adrenal glands, there may be an option to remove it surgically, curing the dog. The other problem is that those 15% of tumors which are in the adrenal glands are occasionally malignant. By the time you get around to doing further tests, such a tumor might be inoperable. Also, dogs in this 15% often need a much higher dose of medication than dogs with pituitary gland tumors.

What Are The Treatment Options For My Dog?

There are four commonly used drugs to treat Cushing’s disease in the United States: Lysodren® (= mitotane or o.p’-DDD), trilostane (= Vetoryl®), ketoconazole (= Nizoral®) and L-Deprenyl (= Anipryl®, Eldepryl®, selegiline).

All drugs used to treat Cushing’s disease vary in their effectiveness in one pet versus another. This is probably due to individual variations in metabolism of the drugs between pets and to differences in the characteristics of the pituitary tumor in one pet versus another.

Some vets delay or do not treat suspected mild cases because of their experiences with the side effects of lysodren and trilostane. (their thoughts are: many of these pets are elderly and frail with multiple health problems, and they might pass away first from something else other than Cushing’s disease) Not all dogs need immediate treatment. A survey in 2001 found that over 50% of specialists would not treat a dog that had minimal signs, no mater what the pet’s Cushing’s test results were. I personally would hesitate to treat an older happy, content dog with the more powerful of these drugs if the owner’s major complaints were a sparse hair coat, skin or ear infections that were responsive to other treatments, obesity or high triglycerides level. I have other ways to deal with those issues. High blood pressure can also be dealt with in other ways. When standard blood pressure medications no longer worked or when serious infections, severe muscle weakness, diabetes or nerve-related problems that were likely due to the Cushing’s problem threatened, I would begin one of the first two medications. Other vets would treat more aggressively based on their personal experience, philosophy and the resources at hand. On rare occasion, trilostane has caused the reverse disease, Addison’s disease (aka hypoadrenocorticism) to occur in which too small an amount of cortisol is produced by your dog’s adrenal glands. The primary signs when that occurs are weakness, loss of appetite, vomiting, tremors or diarrhea, in that order. Fortunately, most dogs that experienced that problem recovered within 6 months once their trilostane dose was lowered or discontinued. (read here)

It is also important that any other health problems your pet may have be stabilized as best as possible before Cushing’s treatment begins. Heart problems need to be stabilized with appropriate medications, low thyroid function (hypothyroidism) needs to be corrected. Diabetic dogs need to be stabilized with insulin and any problems associated with chronic kidney disease need to be addressed.

Lysodren® (= mitotane aka o.p’-DDD)

The generic name of this medication is mitotane. It is the drug that has been used the longest to treat hyperadrenocorticism in dogs. It is relatively inexpensive.

Lysodren® has the potential to cause serious side effects. Dogs receiving it need to be monitored closely through periodic blood tests and owner observation. Many vets suggest a repeat of your pet’s ACTH stimulation test a month or so after beginning lysodren and twice a year thereafter. If response to lysodren is inadequate, after about two weeks your dog’s dose might need to be increased. It takes 4–6 months for all the signs of Cushing’s disease to dissipate when lysodren treatment is successful. However, your dog’s water consumption and urination habits should return to normal much faster than that. Hair is often the slowest thing to return to normal.

It is not unusual for your dog’s required dose to change over time. (Phenobarbital, given for epilepsy or insulin, given for diabetes, can interferes with the drug’s action and require dose adjustment down or up)

Side effects, due to lysodren are quite common. They include loss of appetite, vomiting, diarrhea, “mopiness” (lethargy) and incoordination.

These side effects are usually due to an excessive or rapid drop in the pet’s cortisol levels (too much drug for that particular pet). They can be fatal. If you use lysodren, have your veterinarian dispense an appropriate dose of prednisone tablets or injection to give in emergencies when the vet might be unavailable (if a 24-hour veterinary emergency center is not close by). Plan for an emergency before one might occur.

Your veterinarian might begin with a more substantial daily dose (a loading or induction dose) than that required for long-term maintenance of your pet – just to get the disease quickly under control. The first 7 – 14 days of treatment with lysodren is its “induction period”. During this period, the drug is generally given twice a day. Lysodren is only well-absorbed if fatty food is present in your pet’s stomach. So feed the dog when you medicate it. At the end of this period, your veterinarian may suggest another ACTH stimulation test to see if the dog’s adrenal glands are now working properly. (A good sign you hope to see is a reduction in your pet’s thirst and appetite to what it was before its illness.) Lack of interest in food all together is more likely a sign of lysodren toxicity or another concurrent medical problem.

Most vets suggest you begin this loading period when you are not preoccupied with life’s many distractions and when you are certain that your favorite veterinarian will not be out-of-pocket. The lysodren dose for every dog must be individually tailored and carefully monitored – particularly when beginning treatment. This is because there is always the danger that too much adrenal tissue will be destroyed. Your veterinarian will only see your pet occasionally, it is up to you to be watchful and vigilant. Once your veterinarian is reasonably certain that the lysodren has decreased your pet’s adrenal cortisol secretions to normal levels, your vet might reduce your pet’s dose frequency – perhaps to once or twice a week. Every case is different. Contact your veterinarian immediately if any of the side effect I mentioned earlier occur (or if anything worrisome occurs). Individual veterinarians make many modifications to the procedure I have described based on their personal experiences. If your veterinarian suggests a lysodren regimen or protocol that differs from mine – follow your veterinarian’s instructions!

Trilostane (Vetoryl®, Modrenal®)

Trilostane is a newer option for pet owners in the USA. It has been used longer in the UK (It was licensed by the US FDA in 2009 for canine Cushing’s). Trilostane works equally well for pituitary (PA, PDH) and adrenal (AT, ADH) hyperadrenocorticism cases. It is, perhaps, somewhat safer than Lysodren and its success rate is about equal to that of Lysodren.

Trilostane’s effects are quite similar to those of lysodren – although some believe that it is not as severe in its effects on adrenal tissue as lysodren. Others believe that the effectiveness and risk of one is about the same as the other. Many veterinarians feel that trilostane should not be given when your pet’s kidney or liver tests are abnormal or when certain heart medications have been administered in the recent past. The drug seems to work best when the suggested daily dose is divided and given every 8–12 hours with food (no more than one calculated total daily dose per day).

Positive signs that the medication is working include increased activity, more exercise tolerance, decreased thirst and urination and less panting. Negative reactions to look for include vomiting, lack of energy, listlessness, diarrhea and loss of appetite. These signs do often go away or lessen with time or dose adjustment, but always bring them to your veterinarian’s attention immediately.

Pre-marketing research conducted by the pharmaceutical company indicated that trilostane should be less capable of producing the occasional (and even irreversible) adrenal gland damage (Addisonian reaction) than Lysodren. This now appears to be untrue. So dogs on trilostane need to be just as closely monitored as those on lysodren. That is also why I suggest that prednisone tablets or injectable corticosteroids always be available at your home for emergencies if a veterinary 24-hour emergency center is not close by. Just the trip to an emergency center in a cortisol-depleted dog can make matters worse.

As with lysodren, the drug must be begun cautiously and ACTH stimulation tests need to be run periodically to judge the drug’s effectiveness.Although trilostane must be given more frequently and at a higher cost, it is an alternative for dogs that do not tolerate lysodren well. If you contemplate switching your pet from lysodren to trilostane, it is perhaps safest if a month passes after stopping the lysodren before beginning the trilostane.

There is some recent data that suggests that in some situations, trilostane (and probably lysodren as well) might make pituitary tumors grow more rapidly. (read here) In humans, a somewhat similar phenomenon is called [chemical] Nelson’s Syndrome. Trilostane can also cause adrenal glands to increase in size.

Anipryl® (= L-Deprenyl, levodeprenyl, Eldepryl, Carbex, selegiline)

The powerful potential side effects of lysodren led veterinarians to look for alternative medications to treat hyperadrenocorticism disease. One of these, l-deprenyl (Anipryl), became available in 1997 as a spin-off of human Parkinson’s disease research. (Veterinarians also use Anipryl to treat canine age-related mental decline = canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome) When Anipryl is beneficial, it is only when the root of your dog’s Cushing’s problem is a pituitary tumor. It has not been found to be very effective when your pet’s problem is caused by adrenal gland tumors. The medication works by regulating dopamine, a signaling (neurotransmitting) chemical in your dog’s brain and pituitary gland. When dopamine levels are high, portions of the pituitary gland are thought to stop sending ACTH signal messages to your pet’s adrenal glands instructing them to produce cortisol.

Anipryl has much fewer and less serious side effects than lysodren or trilostane. Perhaps 5% of the pets receiving it will experience gastrointestinal upsets, restlessness or disorientation. Veterinarians generally dispense a daily dose for two months, gradually increasing the dose if the initial dose was not sufficient. There are some drug interactions that need to be avoided. (certain mange dips, antidepressants, incontinence drugs, certain narcotics and narcotic patches, etc.)

At best, it seems that Anipryl is an effective alternative to lysodren therapy in 20 –40% of canine Cushing’s patients. Some theorize that it only helps when pituitary gland tumors are located in areas sensitive to dopamine. As Anipryl is metabolized in your pet’s body, stimulatory chemicals are produced (the base structure of Anipryl is methamphetamine). (read here) So it can be difficult to determine if improvements in your dog’s mood and activity on Anipryl are actually due to its effects on cortisol. I think it would be better if you judged this drug’s effectiveness in your pet based on a return to normal water intake, urination and lowered alkaline phosphatase blood levels.

If your dog experiences major side effects on lysodren or trilostane, you can give Anipryl a try. But be prepared to return to your pet’s former medication if you are not satisfied with Anipryl after a few months’ use. Unlike an ACTH stimulation test to judge the effectiveness of lysodren or trilostane, there is no hormonal test that I know of to judge the effectiveness of Anipryl in your dog. You yourself will have to make that judgment.

Ketoconazole

Ketoconazole is an antifungal drug that also has effects on the endocrine gland system. It is generally not the first choice of veterinarians or physicians for hyperadrenocorticism disease treatment. But it is occasionally given when other drugs are ineffective or produce too many side effects. About half of the dogs with Cushing’s disease are said to benefit from the drug. However, improvements seen on ketoconazole are often incomplete or temporary – making it difficult to differentiate any positive effects from a natural, temporary downturn in Cushing’s disease symptoms. When it does appear to work, it seems about equally in its effects for pituitary (PA, PDH) and the adrenal (AT, ADH) forms of Cushing’s disease. Generally, pets on ketoconazole for hyperadrenocorticism disease are observed for a week or two on a low dose and, if they tolerate it well and the drug does not cause vomiting or diarrhea, the dose is gradually increased. An ACTH stimulation test is desirable after a month or two on the medication to see if it is actually helping. Ketoconazole and Anipryl are not my first choices in treating Cushing’s disease. But in one study, veterinarians did report good results using ketoconazole. (read here)

Are There Other Medications That Might Possibly Help?

Because physicians and veterinarians are highly motivated to find less toxic treatments for Cushing’s disease, articles on a large number of alternative treatments appear in the literature. None have replaced Lysodren or trilostane as the two front-line drugs. And because ACTH levels and the symptoms of hyperadrenocorticism naturally cycle (go up and down on their own) it is hard to gauge how effective these treatments really are. But here are some:

Retinoic Acid

Retinoic acid is a compound similar to vitamin A. One study appeared to find that administering this compound reduced the size of pituitary tumors in Cushing’s disease cases in dogs. They found its efficacy (positive effects) about the same as ketoconazole. (read here) More recent human and cell culture studies tend to confirm retinoic acid’s effectiveness. Do not give excessive amounts of vitamin A or retinoic acid to your pet without veterinary supervision. In excessive amounts, they are toxic. If your veterinarian finds RA or related compounds to be effective in treating Cushing’s disease in your dog, I would appreciate your letting me know.

Cabergoline

Cabergoline, like Anipryl®, interferes with the pituitary gland’s dopamine system. It has been used to treat a diseases caused by other types of pituitary tumors (prolactinomas and tumors that secrete growth hormone) in humans. It was reported to be useful in about 40% of dog Cushing’s cases (read here) – although in humans, it seems to lose its effectiveness over time.

Mifepristone And Thiazolidinedione

Mifepristone is the same compound found in certain “morning after” pills. Another ability of this drug is to make the body resistant to the effects of cortisol. So, it has been used to counteract the effects of excessive cortisol produced by the adrenal tumor (AT) form of hyperadrenocorticism disease. It could, conceivably, be helpful in the 15% of dogs in which tumors are located in the adrenal gland but which were found to be surgically inoperable for one reason or another. It initially appeared that thiazolidinedione compounds, or drugs with similar actions might control Cushing’s disease without the side effects of current medications. (read here) Although the work looked promising at the time, later trials showed that the tumor cells resumed their excess ACTH production after about 6 months.

What About Holistic, Homeopathic And Other New Age Treatments – Might They Help My Dog?

Whenever you are dealing with an incurable disease in a human or a beloved pet, an opportunity presents itself for hucksters to market worthless, unproven and scientifically untested remedies. The fact that the symptoms of Cushing’s can wax and wane without treatment and the difficulty of being 100% certain of one’s Cushing’s diagnosis makes evaluation of these products all the more difficult. For example, a British vet reported superb Cushing’s disease cures using a mixture of grain alcohol, acorns and “essence” of ACTH. (read here)

I am a product of the practical folks of the Illinois plains and the National Institutes of Health; so I don’t believe in homeopathy or other “alternative”, “complementary” or mystical techniques that have no scientific explained. If any of those things have benefits, I believe they are in offering solace to grieving dog owners desperate to do something – anything – for the pets that they love so dearly. There is absolutely nothing wrong with that. Besides, your dog keys off of your emotions – it worries when you worry; it is happy when you are happy. And that worry, tension and stress elevates cortisol levels in your pet as well as in you. (read here)

Melatonin

Melatonin is a hormone that pulses during the day in the blood of humans and animals. It also rises in 24-hour cycles that help establish hormone rhythms in many endocrine glands. It is also a powerful antioxidant. It is secreted by the pineal gland at the front of your dog’s brain. It reaches its highest levels at night. It is commonly sold as a sleep aid. Laboratory experiments have found that low levels of melatonin stimulate the growth of certain types of breast and prostate cancer cells while adding melatonin to these cells seemed to slow their growth. It has been suggested by endocrine specialists at the University of Tennessee veterinary school that melatonin might help dogs with hyperadrenocorticism and there are a few human studies that indicate it might slow the growth of endocrine tumors as well. I would not rely on melatonin as the primary treatment for Cushing’s disease in my dog, but there probably is no harm in giving it.

Lignans

Lignans and Ligands are not the same thing. Lignans are a type of plant estrogen (phytoestrogens) and antioxidants, while ligands are compounds that bind to metal atoms. It is confusing because they have both been suggested as having a role in Cushing’s disease treatment. (read here) Lignans are also suggested by the University of Tennessee as a therapy for “atypical” Cushing’s disease (read about that lower down). Two forms are available at health food stores. There is some sketchy data that consuming lignans might reduce male and female hormone levels in humans. But also reports of other lignans causing Cushing’s disease. (read here & here) I know of no controlled studies of either melatonin or lignan use in the treatment of Cushing’s disease in dogs. As with most nutraceuticals, there is probably no harm in adding either compound to another, well-thought-out, treatment plan.

Are There Any Non-Drug Treatment Options?

Yes, but only occasionally are they attempted:

Surgery To Remove Pituitary Gland Tumors

Your pet’s pituitary gland is located in one of the most inaccessible locations in its body – in a tiny bony vault just below its brain. It is surrounded by an intricate and fragile network of blood vessels (read here) that can easily be torn during surgery. Nevertheless, surgical removal of pituitary tumors in cases of Cushing’s disease is routinely done in humans. You can see the devices that are used here. Pituitary surgery is a much less common procedure in pets. I know of only one veterinary center in the United States attempting it in 2018. (see here) Another advanced veterinary center in the Netherlands pioneered and performs this intricate procedure more frequently (Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Utrecht University). That might be because almost half of the dogs in the Netherlands have good health insurance vs 2% in the USA. However, I believe that some US-written pet health policies, will pay these costs anywhere in the world – of course, not for preexisting conditions.

Because veterinarian surgeons generally remove most of the anterior portion of the pituitary gland; following this surgery, there is the danger your pet will be left hypothyroid, deficient in cortisol (Addisonian) and possibly also with a rare form of diabetes (diabetes Insipidus).

Surgery To Remove Adrenal Gland Tumors

Although it is the much less common form, if your veterinarian identifies a tumor(s) in one of your pet’s adrenal glands, that gland might be removed through surgery (adrenalectomy). It is also a ticklish surgery that is best performed at a veterinary surgical center by a specialist in the procedure with access to sophisticated magnifying or robotic equipment. That is why this surgery is not commonly performed in dogs. In many adrenal gland-located cases the tumors(s) are small, diffuse, and can be nearly impossible to see. These tumors are also sometimes malignant and have already spread to other inoperable locations. They are also often diagnosed when a dog is at an advanced age and at a higher surgical risk. Postoperative complications after this surgery are common. This is because the normal remaining adrenal gland is often shrunken and has lost much of its ability to produce the pet’s minimum requirements of cortisol. Sometimes, a post surgical period on prednisone does give the pet’s remaining adrenal gland time to recover. It is also possible to attempt to destroy these tumors (and the rest of the pet’s adrenal glands) with higher doses of lysodren. Dogs that have had this done, accidentally or on purpose, then have the Addison’s problem to deal with and will need supplemental prednisone and, possibly, a second hormone replacement (Florinef, percorten-V) for the rest of their lives. (read here)

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy, similar to cancer treatments in humans, is an option for certain pets with the pituitary tumor form of hyperadrenocorticism. Radiation will destroy pituitary tumors. The problem with the technique is the collateral damage that inevitably occurs in pets and people. It is best reserved for large pituitary tumors that are compressing nearby portions of the dog’s brain and causing things like blindness, seizures, personality changes and difficulty getting about. In those cases, it is a valid alternative to surgery (hypophysectomy). The primary symptoms of Cushing’s disease rarely disappear after radiation therapy, but the tumors usually shrink and their local effects on the surrounding brain tissue often lessen as well.

What Is The Outlook For My Dog?

Cushing’s disease is not a painful condition. The most important thing is that your pet be happy in its autumn years – and you are a much better judge of that than your veterinarian. If your pet can still do the activities with you that give you both pleasure, you can just accept the diagnosis, or you can ask your veterinarian to prescribe some of the less severe – but unproven treatments. Some owners confuse the normal declines and loss of organ capacity that come with aging for symptoms related to Cushing’s disease. It can be very hard for us veterinarians to sort them out as well. Many cases really do need some form of treated – but not all of them do. When, in the future, owners and veterinarians have wider access to more precise surgery and better targeted drugs, that will change. I only write these articles sporadically, but new discoveries are made every day. My best advice to you now is to try to find a veterinarian whose philosophy matches your own and let that person suggest the treatment options for your dog.

Elevated blood cortisol makes dogs with Cushing’s disease more susceptible to infections. So, they need extra attentive care, good nutrition and a low-stress, stable life. The most dangerous time is the first six months after treatment begins. None of the treatments we have, actually restore healthy pituitary/adrenal (HPA) function; but once that six-month period has passed, dogs with the disease may have several more good-quality years ahead of them.

Accidental (iatrogenic) Cushing’s Disease

The same signs we see in pets with a malfunctioning pituitary-adrenal gland system (Cushing’s) can be caused by giving pets cortisol-like medications for too long a time. Many common veterinary medications contain a corticosteroid ingredient (e.g. cortisone, hydrocortisone, prednisone, prednisolone, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, etc.). These medications are very important in veterinary medicine. They can be life-saving. But given them in large doses or over long periods of time, can cause “accidental”(= iatrogenic) Cushing’s disease. Even topically applied, beclometasone, betamethasone and budesonide, steroids have, on rarer occasions, caused Cushing’s-like symptoms.

When your veterinarian prescribes corticosteroids for long periods, it is usually because there is no other treatment option available. For many sick pets, the mild to moderate Cushing’s-like side effects and weight gain of periodic, or intermittent corticosteroid use are preferable to the pain and debility of the condition being treated. But never give more than is absolutely necessary and be mindful of the side effects they might cause (many of these steroid treatments are for autoimmune or allergic skin diseases). There are alternatives, such as cyclosporin, but they have their own drawbacks as well. (read here) When iatrogenic Cushing’s disease occurs, these compounds should not be suddenly stopped. Usually, when they are gradually withdrawn, your pet’s adrenal glands and pituitary will return to normal function. Although it is generally not required, an ACTH stimulation test can distinguish between true Cushing’s disease and the Cushing’s-like symptoms of steroid over use.

My Veterinarian Thinks My Pet Might Have “Atypical Cushing’s Disease” – What Is That?

Veterinarians have always been perplexed by a percentage of dogs that have one or more of the symptoms that are seen in hyperadrenocorticism but test negative for Cushing’s disease on the low dose dexamethasone stimulation test, the ACTH stimulation test and the urine cortisol:creatinine ratio test. That is because the pituitary gland is such a complex organ with so many different cell types (“secretagogue cells”) “talking” and interacting with one another. There are at least six cell types in close proximity to each other, each with a different responsibility. Each communicates chemically with its brethren as well as its target organ when making decisions. Everything the pituitary gland does is a group effort.

These nonconformist dogs, with normal cortisol tests but signs of endocrine illness (e.g. eat, eat, eat, pot-belly, thin hair coat, peeing & drinking more, ALP blood enzymes above normal), were labeled by some veterinarians as having Atypical Cushing’s Disease. That was an unfortunate choice of words because in human medicine, Atypical Cushing’s Disease refers to the opposite situation, higher than normal blood cortisol and positive ACTH/Dexamethasone test results but few or no disease signs or a situation where tumors in other areas of the body (often the lungs) raise blood cortisol levels. There are tests to help identify these dogs. the University of Tennessee Veterinary School offers various blood tests that some claim are helpful in identifying some of those cases. Others disagree.

Your pet’s pituitary gland is a vast hormone-producing factory – the “master gland” (with 9 pituitary hormones known as of this writing). It and your pet’s adrenal glands have cells that are “plastic” or multi-potential and have the capacity to produce many hormones and hormone-like compounds as well. (read here) There is no doubt in my mind that these processes can go wrong at many different points, producing many different steroid-hormones other than cortisol which might cause symptoms similar to Cushing’s disease in your pet. But, in my way of thinking, if your pet’s signs are not due to elevated blood cortisol, your pet does not have Cushing’s disease – typical, atypical or otherwise. (read here) I think Harvey would agree. What it has, is another of the many hormonal problems that involve the pituitary-adrenal axis.

Is There A Link Between Early-Age Spay/Neuter And Cushing’s Disease Later in Life?

Yes, I believe there is.

I have no definite proof, no one has added the numbers, but much scientific data suggests it.

This section should be nearer the beginning of this article because it is so important. But it is where I break my promise to keep things simple : Veterinarians now know, that early age (pediatric) castration of male dogs and early age spaying of female dogs (before their first heat period in females, before signs of puberty in males) increased their susceptibility to a large number of serious and often incurable diseases (weak ligaments, hypothyroidism, diabetes, obesity, incontinence, urinary tract infections, a variety of tumors, etc.). Increased susceptibility to traditional hyperadrenocorticism disease is rarely mentioned.

But healthy levels of female and male hormones in youth are crucial to the normal development of the pituitary gland and the adrenal glands in all species that have so far been studied. When natural levels of either of these hormones are not present, how the pituitary becomes “wired” how it communicates through ACTH messages with the adrenal glands and when and how much cortisol is released significantly change. In some situations (e.g. stress) testosterone and estrogen put the brakes on ACTH and cortisol production. I cannot tell you that the lack of testosterone and estrogen from early spay/neuter alone caused Cushing’s disease in your dog. But neutering your pet before the age of puberty certainly did not help matters.

Here are some major clues that suggest that: Both the cells in your dog’s pituitary gland that produce ACTH (the corticotropes) and those in its adrenal glands that receive their messages to produce cortisol contain receptors for male and female hormones. The receptors for female hormones that would have been produced by the missing ovaries are ERα and ERβ the receptor for male hormones is the AR receptor. These receptors or sensors are Nature’s “eyes” on the endocrine system. They are never located in the body randomly. They are placed where they are for a reason – to change the activity of the cells on which they reside. When the cells on which they are found (in this case the pituitary corticotrope cells that produce ACTH) produce hormones, an important function of these receptors is to turn hormone production on or to turn hormone production off depending on how much sex hormone the sensors measure in the blood stream. In your dog with Pituitary Dependent hyperadrenocorticism (85% of all cases), they are not turning off.

When your dog is neutered or spayed, the amount of those regulatory sex hormones that are present suddenly drops. The receptors in your dog’s pituitary and adrenal gland corticotropes are well aware of that drop. Both male and female hormones can be stops (inhibitors) on the amount of ACTH pituitary cells produce. Most of these dynamics were worked out in rats in an attempt to understand what happens in women at menopause or in both sexes during high-stress events when more cortisol needs to be generated.

Sex hormone receptors are also present in the portion of the brain that lies just above the pituitary gland – the hypothalamus. Some of those cells produce another hormone messenger, CRH, which also encourages pituitary ACTH production. That results in more cortisol being produced by the adrenal glands. In the absence of sex hormones, cells in the hypothalamus produce more CRH. (read here)

A second important messenger chemical, PACAP also comes into play. It, too, is produced just above the pituitary gland, and it too is sensitive to the amount of sex hormones present in the body. Lack of sex hormones encourages its formation. Receptors for PACAP are present in the pituitary. They are present in the adrenal glands as well. When sex hormone levels drop, that increase in PACAP also encourages the formation of ACTH and cortisol. What might be of particular interest to those who deal with canine “Atypical” Cushing’s disease is the fact that in certain experiments, removing the testes or ovaries causes certain cells in the adrenal gland to transform into abnormal sex hormone generators. Excess sex hormones are thought by many to be the underlying cause of the “Atypical Cushing’s disease I mentioned earlier. I do not know if some of the available steroid implants or selective antagonists might be beneficial to some of these dogs.

What should be of interest to you as a dog or cat owner is that the age at which sex hormones drop due to neutering and spay is likely to be very important in determining the future behavior of your pet’s pituitary gland. Depending on when hormone surges occur or do not occur, circuits and internal connections are permanently molded differently. Before birth, sex hormones mold the shape and anatomy of the body. After birth in the young, they have other, critical chores. After puberty the sex hormone-responsive signaling system can have the opposite effect or less of an effect than it did before puberty. When you agree to have your dog neutered too young, you expose your pet to the risk of ACTH and cortisol over-production, pituitary and adrenal gland malfunctions, tumors and Cushing’s disease. Cat owners might take heed as well because diseases like feline acromegaly and some feline diabetes share the same risk factors.

Not all cases of hyperadrenocorticism are caused by early spaying or neutering. Genetics and lifestyle undoubtedly come into play as well. But I believe that in a sizable number of cases, spaying or neutering your pet too young probably played a role. So, when the spay/neuter bus arrives next time, “just say no” to early age neutering.