A Wildlife Rehabilitator’s Guide To Animal Nutrition And Diets

Ron Hines DVM PhD

All Of Dr. Hines’ Other Wildlife Rehab Articles

All Of Dr. Hines’ Other Wildlife Rehab Articles

Weigh Your Feathered & Furry Babies Frequently

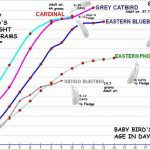

Keeping track of your wildlife resident’s weights is the most accurate way to catch potential problems early while they are still correctable. If you search online, there are graphs that show the normal growth curves of almost any animal you will be caring for. A deviation down from that curve is often the first warning that the animal has a problem. And that problem might relate to nutrition, or it might be an early warning of another budding health issue. It might be an intestinal parasite problem. It might be a vision problem. It might be stress associated with nearby animals or activities. It might be unsuitable caging. Or it might just be the frequency and way in which the animal is being fed and tended to. Wild animals are very perceptive, and no two volunteers are going to perform their tasks identically.

How Well Do Nutritionists, Veterinarians, And Others Understand The Nutritional Needs Of Wild Birds And Other Wildlife?

Not well.

The best most veterinary nutritionists can do is observe what a particular species of bird might eat in the wild. That shifts with the season, and what data we have is often incomplete. The rest of the information is taken from what poultry scientists know about the nutritional needs of domestic chickens, turkeys, and ducks. However, poultry genetics have been modified over millennia to maximize their value to humans and to thrive on what humans cultivate. Only one nutritionist I know of, Dr. Tom Roudybush, actually identified some of the nutritional requirements of a few select non-poultry species. (read here)

When it comes to wild mammals, nutritionists choose the most closely related domestic animal and develop feeding suggestion from that. So, all commercial diets for wild birds and mammals need to be considered as informed guess work. Mother Nature is not as predictable in supplying wildlife with nutritionally adequate diets as humans are to domesticated animals. So, there are likely to be some wildlife nutritional surprises yet to be discovered. (ask me for Oroz2014)

Why Do Infant Animals – Especially Baby Bird, Need To Be Fed So Often?

The faster an animal grows, the more nutrients (particularly protein) its body demands. That is particularly true of songbirds. Besides their fast growth, these birds have high body temperatures, which translate into a high metabolic rate and the need for abundant calories. I stepped into my aviary room a few minutes ago. The cloacal (“rectal”) temperature of an obliging 58 gram South Texas nighthawk (pauraque) was 104 F/40 C. A 20 gram South Texas flycatcher (kingbird) – about a week before release – had a cloacal temperature of 108.4 F. You don’t notice how warm these birds are when you handle them because their feathers trap the heat against their bodies. So typical young nestlings need to be fed every hour – dawn to dusk. Those like doves and raptors that have a crop for food storage can be fed less frequently (owls have no crop, so when fed a whole mouse or rat often show no interest in food until the bone and fur portion of their last meal is regurgitated).

The food requirements of small mammals of all ages is also governed by their metabolic rate (BMR). Their nutrient needs vary depending on whether they occupy a “food rich” environment in nature; as well as on their natural longevity. Long-lived animals (such as tortoises) tend to have lower nutrient needs. You can read more about that here. Occasionally, people will bring you “field mice” that turn out to be short-tailed shrews. Shrews need to eat about half their body weight per day. I provide them with earthworms every 2–3 hours. Of all mammals, shrews have the highest metabolic rate and need for calories. (read here)

Some Of Your Diet Choices:

I doubt that two wildlife rehabilitation facilities in the United States feed the same dietary ingredients in the same amounts or frequencies. It is a tribute to the adaptability of wildlife metabolism that they can both be just as successful in the number of animals they eventually release. Websites, and handouts are filled with specific recipe suggestions. Some provide detailed recipe instructions and some do not. Here are three that, I believe, are good choices:

The Formula For Nestling Songbirds (FoNS©).

The Formula For Nestling Songbirds (FoNS©).

Dr. Mark Finke – An Animal Nutritionist and entomologist based in Rio Verde, Arizona and Dr. Diane Winn, Co-director of Avian Haven in Freedom, Maine – one of the largest avian rehabilitation facilities in New England – developed this recipe for juvenile songbirds. “Songbirds” doesn’t necessarily mean they have a beautiful song. People who study birds (ornithologists) use that term for birds that perch and belong to a particular group of birds called passerines. The blue jay being released in my fanciful drawing is a passerine bird. The bald eagle most certainly is not. It is a raptor. Dr. Finke, knowing the commercial pet food industry well, was searching for a readily available, economically base diet that would be high in protein (~40%), high in fat (~20%) and which also contained vitamins A and D in moderation. Dr. Winn had the birds and resources to try it out. Even songbirds that, as adults, consume mostly fruit and seeds, feed their babies primarily insects because fast-growing baby birds have protein needs far above those found in seeds and fruit. Not all proteins are created equally, either. For instance, ground up feathers are primarily keratin. So are your fingernails. Keratin is a protein, but neither you nor the birds you rehabilitate can digest keratin in its natural form. In 2006, they settled on commercial ferret food as being the closest readily available base product to what they wanted and to that they added chicken-based baby food, dried egg whites, plain yogurt, calcium carbonate, and LaFeber’s Avi-Era bird vitamins. By 2020, the formula had changed several times due to changes in the base ingredient composition and the opportunity for less costly options that spared wildlife rehabilitators ingredient costs but produced equally good results.

You Can Rely On A Home Prepared Variety Diet That Has Given Me Good Results for 20+ years.

The Diet I Feed Songbirds And Small Omnivorous Mammals: Purina Friskies Shreds, Minced Hard boiled Eggs & Chicken Thighs With Added Grubs And/Or Flies

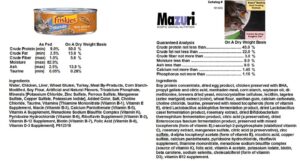

I feed them in the quantity of about 3:2:2:1. The Friskies™ cat food line was introduced in 1956 by the Carnation Company, a manufacturer of evaporated milk products. When Carnation entered the pet food market, theirs was the first commercial diet specifically designed for cats. By 1960, its line of cat food had become the largest selling brand in America. So, it dropped its dog food line and became a cats-only brand. (read here) Nestlé purchased the Company in 2001. The Friskies plant is still located in St. Louis, Missouri as part of Nestlé/Purina Pet Food Products, which currently claims to run 35,000 quality control checks across all of its factories in a typical 24-hour production cycle. The company relies on the “Lean Six” method of quality control and requires GLP training for its line management employees. Since 2011, their Shreds™ chicken-based product ingredients list has remained constant in its protein content, while crude fat and fiber went up by 0.5% on wet weight basis. The product contains no jelling or thickening agents such as carrageenan, guar gum or xanthan gum and relies primarily on non-toxic modified corn starch to obtain its desired texture (some believe that jelling agents such as carrageenan can cause dehydration). An unidentified food coloring ingredient entry not listed in 2011 is present in 2021. Table salt replaced potassium chloride, zinc dropped lower on the ingredient list and manganese went higher on the list. The advantage of this canned product over Purina’s dry cat food kibble is in the fact that the canned product is already 80% water, that in its production all bacteria within it were destroyed and that it is less subject to lipid peroxidation (going rancid). Purina and all other dry kibble manufacturer’s dog and cat foods are sprayed with flavorants (fats and oils/animal digest) after they leave the high-pressure expander, puff up and cool. In that process, any bacteria that might contaminate the product (such as Salmonella) have the potential to be passed on to the animals that consume it. During the last few years, occasional nestling have developed weak legs. Adding powdered B-complex vitamins eliminates that problem. (read here) The grubs I feed now are primarily black soldier fly larva. I find them much easier to successfully grow than mealworms colonies.

You Can Purchase The Mazuri Songbird Diet™ In Powder Form As Your Major Ingredient, Or You Can Rely On Purina Friskies Shreds™ As Your Major Ingredient

You Can Purchase The Mazuri Songbird Diet™ In Powder Form As Your Major Ingredient, Or You Can Rely On Purina Friskies Shreds™ As Your Major Ingredient

Mazuri of Shoreview, Minnesota is a subsidiary of Purina Mills(PMI). When Nestlé purchased Purina’s pet food line, they did not want Purina’s livestock and exotics animal feed division. Nestle’s interest was only in what they correctly envisioned to be the much more lucrative dog and cat food lines. So, Purina’s Mazuri® livestock food business bounced through a number of owners and was eventually acquired by Land O’Lakes. Mazuri’s songbird diet states that their formula was “calculated using data from the nutritional requirements of domestic poultry”. That NRC data was last updated in 1994.

If you compare the Shreds diet to the Mazuri diet ingredients on their label, you will see that their protein contents on a dry weight basis are quite similar (50 vs. 45%). Mazuri lists soy as the largest protein contributor. But when you combine their egg product ingredient with the BHA- preserved chicken content, that difference disappears. Shreds is lower in fat, but supplementing with whole minced eggs will bring that number up. It has never been proven that baby songbirds need fat in their diet. Ash content is hard to compare. Both diets have been supplemented with taurine. A 2011 study contrasted the health and growth rate of one group of songbirds fed only FoNS© and another fed only Mazuri® Songbird Nestling Meal. They reported that the two diets returned equal results. But I want you to understand that it was Mazuri that paid for that study. (ask me for Seage2010)

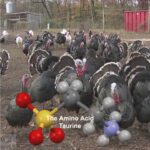

Taurine is an essential amino acid in cats. Perhaps it is in other strict carnivores as well. Animal nutritionists do not know. In adult domestic poultry, taurine is not an essential amino acid. But rapidly growing chickens and turkeys cannot synthesize it rapidly enough to keep up with their tremendous growth needs. That is because meat chickens have been genetically altered to grow abnormally fast (broilers/fryers are slaughtered @ ~7 weeks of age). The meat from the broiler’s muscles that get the most use are the highest in taurine. So chicken and turkey legs are an excellent and affordable source of taurine. However, in the pet food industry, it is only the residual poultry meat that remained on the necks, frames (skeletons) + skin of poultry carcasses that makes its way into the dog, cat, exotics, and wildlife foods that you buy.

Dried lactobacillus acidophilus and various other bacterial fermentation products are added to Mazuri™ wildlife diets as well as other commercial exotic animal diets. The Lactobacillus casei fermentation product you might see on the label is a byproduct of the cheese making industry. It is unclear to me if they add them for the nutrients these bacteria contain or to serve as living probiotic bacteria that might colonize the animal’s digestive tract. Several studies have found that very few of these bacteria are actually alive in processed food products that are advertised to contain them. (read here & here) Besides, none of the bacteria that these products supposedly contain (living or dead) have ever been reported to naturally inhabit the digestive tracts of healthy wild birds or mammals. (read here) Food companies tend to include ingredients that are in current vogue with the public. Whether or not there is hard science to support their inclusion is really not essential to them.

The rosemary extract Mazuri songbird diet contains is an antioxidant and preservative. So is the citric acid. It is thought that most birds can probably synthesize their own vitamin C (ascorbic acid) from the glucose in their bloodstream. But a few bird species (shrikes, flycatchers, swallows, and warblers) appear to have lost their ability to make their own vitamin C.

What Flavors Can Birds Taste? What Odors Can Birds Smell?

What Flavors Can Birds Taste? What Odors Can Birds Smell?

John Audubon believed that birds couldn’t smell. After all, they had no noses. We humans can taste bitter. We can taste many of the savory amino acids found in meat and mushrooms (= umami). We can taste salty. We can taste sour and we can taste bitter. As far as we know, most wildlife can as well. Some odors are a beacon that food is nearby, others are a warning. A good deal of wildlife have odor-detecting abilities far beyond the sensitivity of us humans. Those are often the species with elongated noses. The record holders are buzzards and elephants, both of which can detect odors from a distance of ~12 miles (ca. 19 kilometers) (although there was a 1941 report of an albatross that traveled 64 miles (ca. 103 kilometers) from China Point on San Clemente Island tracking the scent or taste of a galley cook’s bacon drippings out at sea). Click this link or the blackbird above to learn more about the taste and odor-detecting abilities of birds.

Feeding Furry Babies

Milk Replacements For Your Furry Babies:

Milk replacements are designed to supply the young animals you care for with all the energy, amino acids (the building blocks of protein), vitamins, and minerals that they require. Much of what is in natural milk is no more than a distillate of its mother’s blood. So natural milk products contain protective antibodies and hormones as well. But some milk ingredients (lactose sugar, casein and whey proteins) are actually created within the mammary glands themselves. The natural milks of the animals you care for differ widely in the amounts of these ingredients that they contain. When the lactose content of an animal’s milk is high (such as cow milk) the protein and fat content tends to be low. The reverse is also true, low lactose milk sources tend to be considerably higher in protein and fat. There are some notable species differences. Sea mammals produce milk that is quite high in fat and low in protein (perhaps because their young need to quickly produce protective blubber and more energy, both to protect them from the cold of the ocean). While rabbit milk is quite high in protein relative to the amount contained in cow or goat’s milk. As to protein content, small animals like mice that mature quickly produce high-protein milk. Their offspring need it to grow quickly. While slow-growing animals that depend on their mother’s milk for long periods tend to produce a lower protein, higher fat product. The calcium content of the milk of fast-growing animals tends to be higher as well. Fast maturing species are also more dependent on adequate quantities of the muscle building amino acid leucine. For instance, the milk of rodents like rats and mice that can double their birth weight in only four days contains about 11 mg/ml of leucine, whereas the milk of us humans that double our birth weigh in about 180 days contains about 0.9 mg/ml. Cow and goat’s milk contains about 3.3 mg/ml. Cows and goats double their birth weight in about 40 days. When it comes to bottle raising whitetail deer, most wildlife rehabilitators that I know find that fresh goat’s milk (when they can find it) causes considerably less diarrhea (scours) than commercially sold calf milk replacement formulas. That is probably due to the lack of protective maternal (mother’s) antibodies in the artificially produced commercial formulas, as well as the plant-based oils they generally contain. (read about that here)

Milk fat serve as an important source of energy for slower-maturing animal species. The polyunsaturated fats (omega 3 and 6 fatty acids or PUFAs), in milk also aid in the development of the nervous system. Cow and goat’s milk are naturally low in PUFAs. They are also rather low in vitamin D3 and iron when compared to the milk of other animals.

Something that few wildlife rehabilitators appreciate and few suppliers want you to know is that the contents of a mother animal’s milk is not constant throughout the baby’s nursing period. It varies by individual nipple and individual litter size as well. The first milk or colostrum is rich in important protective antibodies. How much of those antibodies enter the baby’s body while it is still in the womb and how much enter through the colostrum depends on the uterine morphology (construction) of the species you are feeding. In general, cold climate and aquatic animals need higher energy (fat) milk to combat heat loss to their environment, while desert animals produce more concentrated milk to avoid their mother becoming dehydrated. It is physiologically impossible for liquid milk to have sufficient protein to provide calories for energy and growth. For that, one must rely on the fat (butter fat) that milk contains. Lactose has gotten a bad rap in the popular press because some humans and animals cannot absorb it. That leads to gas production, colic, and diarrhea. But all natural animal milks contain some lactose. It promotes the absorption of calcium. It provides twice the carbohydrate calories available from an equal amount of blood sugar. With a few exceptions, the water content of the milk of mammals does not differ much in its water content. Opossum milk is about 77% water. bats about 60%, us humans 875, rabbits 675, squirrels 60%, rats 72%, dogs 76%, bears 56%, seals 35%, manatees 87%, elephants 78%, cows 87%, goats 87%. When pioneer wildlife rehabilitators realized the dangers of feeding cow’s milk to infant animals, they turned to Esbilac® marketed for puppies and KMR® marketed for kittens. At that time, it was manufactured by a subsidiary of Bordens. Since then, your choices have balloon – most are shown in the fanciful image I put at the top of this portion.

I recall studies in lions noting that the composition of their milk differed depending on how old their cubs were, how many cubs they were feeding, what they had been eating and even the mammary gland being sampled. Much of that is probably the same for all species. We know it is for cows and us. So, wildlife milk analysis and commercial duplication of wildlife milk replacements is not as exact science as some would which you to believe. So many factors go into the successful rearing of orphan wildlife. People are prone to attribute failures to one brand or another and discount things like their feeding schedule and the amounts fed at each feeding, and to point to one brand or another for their successes or failures. I have seen so many cottontails and squirrels receiving the same formula do well or poorly when nurtured by different wildlife rehabilitators that I cannot recommend one brand over another. What I do know is that micromanaging the contents of these products is considerably more hype than science. That is the trend throughout the dog and cat food industry as well. I also know that the quicker you can get your wildlife weaned onto a solid formula, the better. Be sure to gently massage the babies privates was a soft tissue or cloth moistened with warm water.

Raccoons

When it comes to raccoon babies, you have three milk replacement choices: Zoologic’s Milk Matrix 42/25™ produced by PetAg for nursing wildlife. The traditional KMR™ product also produced by PetAg and sold in almost every pet supply outlet. Fox Valley’s Day One 40/25™ sold through online wildlife rehabilitation supply sites and directly by the Company. Multi-Milk was a very high fat, low lactose ingredient in some raccoon formulas that was once sold by PetAg. It no longer appears on their website.

There is a lot of discussion as to which of these products might be best. But no neutral person has ever split up a number of orphan raccoon litters of the same age into three groups and had the same person feed each group with a different one of these products to observe the outcome.

When wildlife babies didn’t thrive as well as you wished they had, it is common to suspect the manufacturer of the diet might be to blame. It’s only natural that those suspicions tend to resonate and magnify withing the wildlife rehab community. However, how much you feed per feeding, how you reconstitute these products and your general techniques in animal care are just as important. Those are things that you learn from experience and the experience of others you rely on. Some of these babies will arrive at your door star crossed; some years more than others. Perhaps they overheated to the point of organ damage. Perhaps they dehydrated from thirst or in the hot sun beyond recovery. Perhaps they arrived in the early stages of one of the many infectious diseases of raccoons. (read here and here) Perhaps the diarrhea the baby(s) experienced was due to salmonella or some other food poisoning. Perhaps raccoon herpesvirus. Perhaps before reaching you, the kit(s) already had toxic levels of heat shock proteins in their system. When that occurs, failure to thrive can be temporary or permanent. Read about heat shock protein formed by overheating here and here. Over-feeding any of these three formulas can also result in bloat, milk in the lungs and aspiration pneumonia. That can have fatal consequences or simply result in a baby that doesn’t thrive despite all your efforts.

The constituents of all wild animal milk are never constant. The amount of each of the constituents changes depending on the number of kits being fed, the diet of the mother, and even the nipple being sampled. It also changes as the nursing period progresses. There was a small study in 1962 that reported that the milk of raccoons contained 4.9-6.1% protein, 3.9-4.1% fat, 4.7% carbohydrate and 16.2% total solids. (ask me for Whiteside2009) According to another source, raccoon milk contained 4% protein, 3.9% fat, 4.7% carbohydrate and 88% water. (ask me for BenShaul1962) Unlike cow’s milk, the carbohydrate portion of raccoon milk contains very little lactose – a sugar associated with bloat, colic, and diarrhea in orphaned raccoons. (ask me for Urashima2018) None of the three powders store well. One reason is that all high-fat products are subject to rancidity as time goes by. In that process, other nutrients are destroyed. I prefer to purchase formulas and nutritional supplements from suppliers that have the most rapid turnover.

Nature designed raccoons to be omnivores that thrive in a niche where dietary ingredient change with the season. It gave them a brain intelligent enough to seize any food opportunity that presented itself, and it gave them nutritional requirements that were very flexible early as well as later in their lives. When it comes to the protein, fat, carbohydrate, mineral, and vitamin content of these three products, I do not believe that any of them differ enough to be significant. A raccoon kit could thrive on all of them. If there is a brand difference, it would be in the quality of the individual ingredients used to produce the powders and/or the manufacturing methods used. I believe that only Fox Valley states that human-grade products are used.

Cottontail Bunnies, Squirrels And Opossum Babies

When it comes to cottontail rabbits, squirrels and opossum babies, there is even less agreement among wildlife rehabilitators on what to feed than there is for baby raccoons. That is probably because all three are more fragile than infant raccoons and more subject to diarrhea, bloat, and gas problems. Fox Valley recommends their Day One 32/40 formula for all three of these species. But many wildlife rehabilitators are successful using KMR. Kitten milk replacement (KMR) was originally designed for kittens. Cats are carnivores, and some argue that rabbits and squirrels that in nature eat no meat couldn’t possibly thrive on milk formulas that have animal protein and animal fat ingredients in them. However, the growth and survival of all animals require the same amino acids, minerals, and vitamins (other than humans, guinea pigs and monkeys which all require vitamin C). It’s just that herbivore mothers rely on bacteria in their digestive tract to make them. The chemicals themselves are all identical.

For Cottontails, squirrels and opossums, Fox Valley Recommends their Day One 32/40 formula. Others find success with KMR (to which some add various amounts of whipping cream). Some successfully use Meyenberg goat milk, others Esbilac®.

I believe that, just as in raccoons, our feed techniques account for many more of the digestive tract problems we encounter than what you feed – when you choose any of the milk diet formulas that have traditionally been successful. Baby squirrels need to be fed every 2 hours or so until they are 2 weeks old. Baby cottontails can be fed less frequently because cottontail bunnies generally feed their babies only in the evenings and early morning. To adapt to that, baby cottontails have a stomach that holds more milk. For me, feeding them four times a day has been sufficient. As with raccoons, the earlier you can wean bunnies, squirrels, and opossums over to solid foods the better. Avoid high sugar items like supermarket fruit and carrots.

Opossum babies that were still in the pouch when they were found are quite difficult for me to successfully raise (when they weigh less than 15 grams). They weigh about 2 grams when they are born. Once they begin to peek out of their pouch (at ~ 8 weeks) or riding on their mother’s fur (at ~ 10 weeks) they are quite easy to raise. The tiny ones need very frequent feedings (I feed them about every 2 hours during the daytime and 2–3 times at night). For me, the tiniest ones have always been weak nursers. I find it more successful and less time-consuming to stomach tube them. A butterfly catheter with the needle snipped off and flame-smoothed on a 1 cc tuberculin syringe works well. Twenty-four gauge x 3/4” or 22 x 1” IV catheter sleeves also work well. Try getting them to lap from a dish as early as you can. Opossums should be eating on their own by 100 grams. A baby opossum’s eyes begin to open at ~ 65 days of age. They are normally weaned at ~ 10 weeks of age and should be able to care for themselves when they are 3 months old.

The temperature in the container that houses your small opossum babies needs to be kept at about 90 F/ 32 C. If it is much lower, small baby opossums will not digest their milk formula properly. They rely on their mother’s high pouch temperature to aid in their digestion (the normal body temperature of an opossum is 94.6 – 97 F/34.8-36 C). The humidity of the container is also important because the interior of an opossum’s pouch is humid. If humidity drops too low during rehab, the babies’ tail might dry out and slough off. That can be prevented with a damp sponge in a dish in the animal container, as well as a light coating of baby oil on the tail.

Is It Possible To Overfeed Growing And Adult Wildlife?

Yes

A lesser, but just as important, problem is feeding growing and adult wildlife too much. Growth rates beyond what is normal for a species can lead to later joint and bone problems, as well as liver damage when the liver’s P450 enzyme system is over taxed. If you are feeding baby birds, feed only until their crop is 2/3 full. Few wildlife rehabber weigh their chicks frequently enough, but when they do, feeding only up to 10% of the chick’s weight per feeding is the rule. Many species of songbirds will gape for food and beg long beyond what their crop was designed to accept. The most common cause is not feeding frequently enough, but doves, pigeons, sparrows, and grackles seem particularly prone to begging beyond what their crop can healthily hold.That causes over-distention that eventually leads to digestive tract shut-down and an over-stretched crop that is no longer to contract and pass food farther down the bird’s digestive tract. Growing bones also bend under the weight of muscle mass they were not ready to carry. I saw that occasionally in the hunchback penguins of water parks and zoos. It occasionally happens in free living penguins as well when more than two “parents” are feeding the same chick. Pyramiding shells are a common problem in captive turtles fed excessive nutrient-rich diets. In the poultry industry, this leads to slipped tendons, as you can see in the last image of the peacock chick. You can sometimes correct this problem when caught early.

Ducklings and goslings are particularly prone to a problem called angel wing, a deformity where the last section of their wings rotate outward. It occurs most frequently when they are fed unlimited amounts of high-protein diets such as turkey starter or wild game bird starter that encourages rapid muscle growth that exceeds the ability of their joints to support the weight of the wings. Diets marketed for domestic ducks are much too high in protein for wild ducklings. (read here) Make them only a small portion of your wildlife diets. The same goes for rabbit pellets or alfalfa cubes given to cottontails.

Insects -The Natural Diet For Most Immature Song Birds And Many Small Mammals – Even If Berries, Fruit, And Seeds Are Their Primary Diet Later In Life.

The insects that are commonly fed to wildlife in captivity, rehab centers or by the owners of exotic pets are the ones that can be produced commercially in volume at a reasonable cost. They include mealworms, “super worms” – the grubs or larva of beetles – silkworm larva, and for some smaller exotic pets, fruit flies. Earthworms are not insects, but they are grown commercially in large numbers and readily available.

The missing percentages in all these creatures are their mineral content.

Two necessary vitamins that appear to be in short supply in insects that are commonly fed to wildlife are thiamine (vitamin B 1) and vitamin A. Many animals, including humans, can convert beta-carotene, a vitamin A precursor, into vitamin A. (read here) Domestic poultry can convert carotene into vitamin A, deer and rabbits can as well. Turtles and tortoises have that ability too. But no one has determined if or how well songbirds do. Apparently, those birds that normally feed on large amounts of fruit can, while those that normally consume meat or fish have lost all or much of that ability. I rely on the vitamin A in egg yolk, both raw and cooked, and commercial multivitamin supplements to meet the needs of the insect-eating birds in my care. Unlike thiamine and the other B vitamins, too much vitamin A is toxic, so you don’t want to overdo the amounts of vitamin A or vitamin D that you provide.

Much of the protein in insects is in their shells (exoskeleton). How much of that protein is actually digestible for the wildlife you feed remains unknown.

Commercially available insects don’t contain much calcium. Earthworms can contain more if the soils they were obtained from derives from limestone (calcareous/ soils). Creatures in the pill bug family (Rollie pollies) are rich in calcium, and some believe that eating them is how wild bird parents provide their offspring with calcium. I have never fed pill bugs to any young birds for two reasons: Over the years, when I moved objects in the hen house, my chickens greedily gobbled down the wood cockroaches. But they ate the pill bugs reluctantly. The second and more important reason is that pill bugs are known to carry the thorny-headed group of parasites – particularly if they come from an area inhabited by starlings. It’s not only birds that are susceptible to the parasites of isopods. You are too if you eat sushi. However, 15 hours at minus 31 F/-35 C kills these parasites. Perhaps it would kill the parasites sometimes present in pill bugs. No one to my knowledge has ever tried.

Just because you find intestinal parasites in a bird or mammal does not necessarily mean they are causing the animal harm or the cause of a health problem you are dealing with. Many intestinal parasites live in relative harmony with their hosts, doing only minor or no damage to the animals in which they dwell. If an animal is maintaining its weight and appetite and its stools remain normal, they may not be its underlying problem. This photo is from an autopsy of an adult white pelican whose injuries I could not repair. You can see that the worms, although disgusting, and the pelican appear to be living in harmony (commensally) with no evidence of stomach inflammation – just harmless freeloaders living off the pelican’s fish. That will change when food is not plentiful in the wild as they both compete for the same nutrients.

Optimal nutrient tables do not exist for wildlife. So for furry creatures, wildlife experts fall back on the NRC tables we do have – tables for dogs, cats, cattle, rats, mice, and poultry. Using those tables, commercially available insects come up short. Perhaps the wild insects these animals eat in the wild contain adequate amounts of whatever is missing in the bugs that we rehabbers feed. Perhaps we just overestimate some of their nutrient needs. When it comes to calcium and other minerals, birds apparently have mineral sensors in their mouths and seek these minerals out. This photo is of a mineral lick in Peru to which parrots flock to. My solution is to feed as much variety as possible – insects, chopped egg, and cat food, along with a modest vitamin supplement. Dusting and gut loading (feeding the supplements to insects themselves) are other options. I just don’t have the time, resources, or inclination to do that.

Flies & Moths

I find that flies are the easiest insects for wildlife rehabilitators like me with limited funds to obtain. Studies have shown that houseflies have the potential to spread disease and parasites. So, I use the outdoor solar cooker shown in the second photo above and toast them for two days before I store them in the freezer. On a sunny summer’s day, the interior of my cooker reaches 65 C/149 F. I bring the unit in at late afternoon and repeat on the next sunny day. In bush crickets ( we call them katydids) eaten in rural Africa, roasting is said to actually increases in the amount of available calcium and trace mineral elements but did not seem to affect the quality of other nutrients. (read here)

I do not know what the nutritional analysis of adult houseflies are. Housefly maggots are about 60% protein, have a well-balanced amino acid profile, a 20% fat content of which 57% are monounsaturated fatty acids. They, like most insects, are a poor source of calcium. A housefly’s larval calcium to phosphorus ratio is about 0.5:1 (read here) But mature insects are generally less nutritious than their immature forms. I rehydrate them with warm tap water for about an hour before offering them to the birds. Killdeer love them, flycatchers not so much. Night jars will eat them when presented to them with tweezers, but they prefer moths. Birds of the swallow family are the hardest to successfully rehab because, by nature, adults only eat while on the wing. When they are old enough, I place these birds in an outdoor flight with incandescent bulbs that turn on automatically at night to attract night-flying insects. But I net them up in the morning and continue to feed them because I am uncertain how many insects they have consumed. After a week or two, we just leave their cage door open, and they are gone by morning. God-willing, some survive.

Grubs

I keep a compost pile in our backyard. I enrich it with leftover dog and cat food and our household kitchen scraps. I water it frequently to keep it moist in our dry climate. The pile is an excellent source of grubs, wood roaches, earwigs, earthworms etc. for the omnivorous and insect-eating birds that we raise. I believe that it is worth the effort to introduce birds and other animals to their natural local diets as early as possible. Because of the efforts involved in obtaining these natural food insects, they represent only 15-20% of the food intake I supply. The rest is canned cat food, diced eggs, tiny strips of chicken leg meat, crickets, mealworms and oven-roasted flies. The eggs in the photo are those of a soft shell turtle that walked up from the lake behind my house and found the compost pile inviting. I do not know the species of grubs that inhabit my mulch pile. There are ~30,000 species of beetles in North America, and each produces its own grub. No one I know of has reported that any of them are toxic. Most toxic insect larva and adults warn birds away with their bright colorations and bad taste.

The surface and intestines of grubs have a rich bacterial flora. The birds you raise need to be exposed to that healthy bacterial community – read about that here. Natural food items and exposure to their parents are what furnish these microscopic organisms. They are well beyond what commercial probiotics deliver. There are just too many organisms (mostly unidentified and fragile) with one organism dependent on another for their survival for the products you see advertised for birds or wild mammals to be of much (if any) value. Fewer than 20% of the microorganisms found in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) of birds have been identified, let alone grown in the laboratory or commercially. Read about that here. Many are anaerobic and rapidly destroyed by the oxygen in ordinary air. The gut flora of birds is quite different from that of the carnivorous and omnivorous mammals you care for. So if you want to give your baby raccoons and possums yogurt, perhaps it will be helpful. But if you give yogurt to birds, consider its beneficial effects, if any, to be limited to whatever protein it contains. In birds and mammals that consume primarily plant material as adults, the organisms that inhabit their digestive tract also change dramatically with their age. That is another reason why one commercial product for those species is quite unlikely to be of much benefit. As diet, acidity, and gut oxygen levels change, one bacterial or protozoan species is replaced by another. Read about that here.

Diets For Infant Doves And Pigeons

You can read about the diet I prepare to raise doves and pigeons here. They do equally well on Kaytee Exact™. The biggest danger when feeding doves and pigeons is that they will beg for more food than their crop can safely hold. That over-filling eventually leads to fatal crop and intestinal stasis. The most difficult columbine babies to successfully tube feed are those that arrive at your facility close to the age at which they would normally leave their nest. Being imprinted on their parents, they already sense you as a threat, give you the “elbow”, fuss and squirm and refuse to swallow. That makes it difficult to regularly insert a dropper or tube into their crop without eventually injuring their fragile crop lining. Birds of that age will generally already accept a small grain diet. I mill a mixture of millet, corn, and milo so as not to have to add grit. You can see my mill in the second of the two images below.

Domestic Small Grains

The wild grains that doves and finches would normally eat are higher in protein than domestically grown small grains. My preference is to supplement them with diced egg, as a deficiency in protein can cause later problems that are not first apparent. Read more about that here. Grains can also be soaked or boiled to soften them. But left to soak, they tend to become bitter as they begin to sprout. You need to taste them.

A Grain Mill for seed eating birds

Moistened Or Dry Purina Cat Chow

I always prefer providing ground up or soaked cat chow to wildlife rather than dog chow. That is because the pallets (taste sensors) of cats are much more discriminating than the pallets of dogs. Cats are thought to be wiser than dogs when it comes to choosing their food based on nutritional value than taste. (read here) You can pass off low-quality ingredients to a cooperative dog. But you’ll never pass low-quality ingredients off to anything but a starving cat. Pet food manufacturers know that. They do add more grease to feline diets-both to enhance taste and because cats have a nutritional need for more fat calories than dogs do. Diets marketed for cats also tend to have more vitamin A and taurine in them and less fiber. That said, one large wildlife rehabilitation in South Florida does equally well using moistened Purina ProPlan® Canine Chicken and Rice dry kibble as the basis for their songbird diet mix. I would avoid premium dog and cat foods brands produced by independent smaller companies or private label contract feed mills. Quality control at smaller facilities can rarely if ever match those of huge Corporations such as Purina, Mars or Smuckers in their frequency or sophistication of quality control. I generally follow the FDA’s aflatoxin recalls in judging the quality of a pet food manufacturer’s ingredient analysis laboratory.

Chicken As A Dietary Ingredient

I try to offer wild birds and mammals in my care as great a variety of food items as I can. A portion of the diet I feed is often chicken quarters and chicken necks. Most commercial broilers sold in supermarkets are slaughtered between 4 and 7 weeks of age, when only their major leg and wing bones have enough calcium in them to shatter with sharp edges. So, I discard those bones, but I pulverize the rest with a hammer on a concrete surface. These chickens are also obese. So, their meat needs to be cleansed of its fat and grease. Chicken and meat, particularly the thighs, are high in taurine, an amino acid that is probably too low in many diets. A once a week portion of chicken liver provides sufficient vitamins A and D.

I do not feed rehab raptors or owls street pigeons, doves, dead or live intake birds. They are at too high a risk of spreading the diseases and parasites they may be carrying to the rehab animals you are caring for. That is particularly true of pigeons, as they are the most common carriers of trichomonas parasites and the pigeon herpes-1 virus. Domestic poultry chicks have the potential to carry them too, but the likelihood is much less – the larger parasites, like trichomonas, are killed by freezing, If potential avian viruses survive freezer temperatures is unknown.

Eggshells As A Dietary Ingredient

Meat and some insects contain insufficient calcium when they form more than a third of your wildlife’s diet. That is particularly true when the rehab animals are still growing. I collect eggshells from my neighbors, break them up with a mortar and pestle and grind them into a fine powder in a hand-cranked coffee grinder. Eggshells are 95-97% calcium carbonate. The rest is protein. The grinder in the photo above does a good job. More sophisticated electric coffee grinders are available too. How long the ceramic grinder plate in this one will last I cannot tell you. If you purchase that model, put the rickety collapsible handle on an anvil and tap the center articulation rivet with a hammer until it becomes completely rigid in the open position. Don’t attempt to just mash up eggshells in a mortar and pestle. It needs to be a finer powder than you are likely to obtain. If any sharp shell fragments remain, they can cause intestinal irritation when eaten by small animal species that have a low stomach acidity. You can’t just dissolve the calcium carbonate in ordinary tap water. It requires an acidic environment. In general, carnivores and omnivores have the most highly acidic stomachs, while herbivores have the least acidic.

Supermarket Fruits And Berries

Your Local Nuts And Berries

Your immature wildlife needs to become accustomed to the berries and seeds that they normally feed on in your area. Taste, color, and texture preferences develop early in the lives of mammals and birds – and blueberries, currants, citrus and other supermarket fruit are unlikely to be available to them after release. Supermarket fruit also contains considerably more sugar and less fiber (toughness) than what they need to be accustomed to after release. I live in the South Texas area, where rains are unreliable. Most native trees and shrubs here are thorny and all are drought resistant. In the order of my photographs above, songbirds and small mammals here rely primarily on the fruit of brazil, granjeno and anacua, as well as the seed pods of honey mesquite. They also feed on the seeds of our native ebony and sabal palms. Those I feed as I pick them when they are immature. But I boil or grind them first when they are mature and dry.

Mixed Greens

I add diced kale or collard to most of my wildlife recipes. Although not considered “greens,” I add diced broccoli when I am concerned about diet protein levels.

Sprouts

Some folks suggest offering birds in rehabilitation centers, sprouts. But I have offered mixed bean/mung bean sprouts to a variety of birds and animals. Although I know that they are quite nutritional, no birds have ever liked them. I do not know if it is a matter of taste, smell or familiarity, but they generally just ignore them. I ran a test today offering a choice between mixed sprouts and a bird seed mixture of milo, cracked corn and sunflower seeds to the birds that frequent my backyard. I put a steel weight in the middle to keep them in place and filled each dish with a 3/4 measuring cup. Green jays, curved beak thrashers, mockingbirds, sparrows, and long tail grackles and Inca and White wing doves came and went to check it out during the day. One green jay I watched pick up a bean sprout, then spit it out. A couple of thrashers took a look at them, sorted through them for bugs for a moment, and then left. About two thirds of the grain mix was gone by evening. Beans are too rich in protein and carbohydrates to form anything but a minor ingredient in the diets of foregut and hindgut fermenters such as deer, turtles, tortoises, woodchucks, and rabbits.

Grit?

I used to add small amounts of the tiny stones seen in the first photo to the diets of seed-eating birds such as pigeons, doves, chachalacas and quail that I raised for release. I ran a small gravel mix through a series of colanders and screens until I came up with what, I hoped, was the appropriate size grit. However, I am currently just milling their seed mixes to break the kernels (as seen in the second photo) and relying on the birds finding their own gizzard grit after release. That is because I never knew if the size and amount of the grit I added to their diet was appropriate for the species. Read more about grit requirements here.

Individualize Your Utensils And Supplies

When infant birds and small mammals arrive, I place them in inexpensive smooth bathroom waste baskets. Plastic picture frames with window screen glued where the picture would go cover each one. The bottom is lined with 5 inches (ca. 13 cm) of leaf and tree litter, cupped out like a nest. Every week I change the bedding. Between residents, the buckets get scrubbed with a gong brush and 1:20 Clorox™.

Fish Eating Birds

The heron at the bottom of the first photo dislocated his “wrist” If you want to see how I fix avian wrist and shoulder injuries go here. For leg fractures, you can view some options here. Fish spoils rapidly at room temperature. And the fish that are marketed for zoo animals and wildlife tend to be at the bottom when it comes to quality. You can read more about the common thiaminase and histamine problems associated with fish sold in bulk for the consumption of wildlife farther below in the sections on taurine and thiamine (aka vitamin B 1).

You are always safer when you feed fish that have been thoroughly frozen for at least 7 days and then thawed, rather than those that were recently caught. That is because freezing kills many of the parasites that fish transfer between fish-eating birds. One example are the stomach worms of pelicans and cormorants. Mullet are that parasite’s intermediate host. This is the stomach of a white pelican that I autopsied:

Meat-Eating Birds & Mammals

I feed owls and small raptors, live sparrows that I trap. Others prefer frozen mice or rats, and I provide live ones prior to release. Many rehab facilities inject added water (~ 1-2 teaspoon full) into their thawed mice before feeding to assure that their birds of prey stay well hydrated. I feed raptors and owls chicken or calves liver once a week for its high vitamin A and D content. Not all will accept calves liver because of its bitter taste. I feed a variety of animal carcasses as well. Primarily ducks. The safest thing a wildlife rehabilitator can do is to feed as much variety as you can, as early in the animal’s life as you can, in order to prevent deficiencies and prepare the animal for its future life in the wild where food sources are never constant.

Some also add a falconer’s tonic, Vitahawk™. I mix my own vitamin/mineral supplements and have never used it. But I believe their product is a mixture of powdered eggs, protein, prebiotics(fructo-oligosaccharides) that acidify the intestinal tract – hopefully changing gut flora in positive ways, glucose sugar, omega fatty acids and alpha lipoic acid.

How Often Should I Feed?

I feed most feathered and furry youngsters every 2 hours during their first 2 weeks of their lives. That is as frequently as my schedule allows. But some feed newly hatched tiny songbirds such as wrens as frequently as every 15 minutes, dawn to dusk. You are always more successful when you feed small amounts very frequently than larger amounts less frequently. The biggest problem is finding the time to do it. So, I have been known to pull the phone out of the wall, take the batteries out of cellphones and let the mail pile up during the busy spring and summer months. This year, I didn’t find the time to file our income tax until August. All of you have big hearts, or you wouldn’t be caring for wildlife. For us, it is a constant effort to refuse to take in wildlife in need. But I have found over the years that when you overextend yourself, the animals already in your care are the ones that suffer the most. When it comes to furry babies, it is difficult to detect nutritional problems early: A certain dullness you will learn to recognize. Squinting eyes that should be open. A thinner hair coat. Lack of response to touch and sound. Any evidence that the youngster has less energy and strength today than it did yesterday or the day before. But the best evidence of insufficient nutrition is failure to keep up with a normal weight (growth curve) for the species you are feeding.

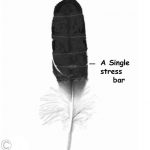

This is my imaginary image of a feather stress bar. Stress bars occur in a bird’s feathers during a period when an unfurled developing feather cannot obtain the amino acids that are required for it to form. That occurs when insufficient protein amino acids are present in the bird’s blood stream. Those required amino acids are in the foods you are feeding. If you see them in growing birds, it is a sign that you are not feeding frequently enough or that your diet lacks quality, complete proteins. When you see them in adult birds, it is a sign of a disease that periodically affects appetite or the ability to feed (forage).

Over the years, I have also found that my success in raising youngsters is greater during the peak of their natural birthing/hatching season than in those that are born either too early in the year or too late in the year. Arriving with nutritional deficiencies due to the parent’s inability to supply adequate food or outright parental abandonment are much greater when animals are born at the wrong time of the year. That might not be true where you live. But I live in an area where rains are unreliable and seasonal. With global warming, you may soon face that as well

At What Age Should I Release Wildlife?

I continue to provide food to immature birds and mammals for a few weeks longer than their natural parents probably would. That is because human-raised wildlife, once released into the wild, will always be at a survival disadvantage when compared to parent-raised wildlife. In songbird studies, that has been found to be true. In mammals, wild mountain goat youngsters with the highest body weights when they first venture out on their own are the ones most likely to survive. (read here & here) That probably occurs in all or most animal species. Perhaps keeping youngsters a bit longer at your facility than their natural parents would, helps even out their odds of survival.

Should I Also Give Vitamins To The Wildlife I Care For, And If So, Which Ones?

Throughout my career, I have learned to trust products produced by Mazuri. If you are feeding an animal a species-specific Mazuri diet, you are already providing all that wildlife nutritionists know about the vitamin and other nutrient needs of that animal. So giving that animal an additional vitamin supplement or tonic could do more harm than good – particularly when it comes to the fat-soluble vitamins A and D. The problem with making unnatural wildlife’s diet nutritionally adequate with vitamin supplements, is that although they save you time and money, they do not introduce you animals to the natural sources of the nutrients they will encounter once you release them. Zoos aren’t going to let their display animals go. So, they don’t care. Their carnivorous animals generally do well when they use Nebraska Packers Meat Complete or Mazuri’s carnivore meat supplements. You also have the option to prepare your own vitamin/mineral mix from human grade ingredients. Read about that here.

People who tend to scientific terms call birds that eat only seeds granivores. The seeds these birds consume are first softened and digested in their fore stomach or proventriculus by the hydrochloric acid and pepsin enzyme secreted there. It then moves a bit farther down their digestive tract into their muscular gizzard (their ventriculus) where it comes into contact with grit and the gizzard’s strong muscles. A churning back and forth action occurs before the grains pass farther down the tract for absorption.

Other birds were designed by Nature to eat primarily fruit (frugivorous) or insects (insectivores). Both also tend to have a well-developed gizzard – either to help them grind the tough fiber that wild fruit and seedpods contain or to pulverize the chitinous shells of insects and the aquatic crustaceans they consume.

The two largest protein reservoirs in birds are its feathers and its muscle. Feathers compose about 4-6% of a live bird’s weight, or about 22-28% of its total body protein. It differs between species, with birds capable of long flight having the greatest feather to body weight ration. Feathers are particularly rich in cysteine, which, along with other amino acids, must be continually supplied to growing and molting birds. When it is lacking, either due to the poor appetite or health issues, inappropriate diet or starvation, the most obvious sign you will see are stress bars on the bird’s feathers.

Raptors and owls do not have well-developed gizzards. Hawks and eagles retain much of their recently consumed prey in their lower esophagus, which serves as their crop. From there, it slowly moves down to their glandular stomach for digestion. Indigestible portions are brought back up (regurgitated) as casts. Owls do not have this esophageal/crop-like compartment. So, their food moves directly to their glandular stomach. Some believe that the lack of that compartment makes owls less efficient in digesting the food they consume.

Cultivated seeds tend to be higher in carbohydrates and lower in protein than the wild grains from which they were developed. Cultivated sees such as sunflower and safflower seeds are also considerably higher in fats and oils than their wild ancestors. These seeds also tend to be deficient in vitamin A, minerals, fiber and total protein and specific amino acids. (read about that here & here) These domesticated varieties also tend to contain fewer antioxidants, less bitter taste.

When it comes to meat-eating birds and mammals, domesticated livestock and poultry as provided by wildlife rehabbers as enormously more fat than wild prey animals these creatures normally consume. Although the raptors I care for reject domestic poultry from which the fat has not been removed, some animals are attracted to these high grease diets that are harmful to them. (read about that here)

Even after pealing off all the fat and skin, chicken breast still has 4 gm of fat /100 gm of meat while that of a wild dove 1.8 grams and wild turkey 1.1 grams respectively.

Birds in particular are creatures of habit. Once accustomed to a homogeneous shape, size, taste and color, it can be quite difficult to get them to accept new food items.

Opossums

Regarding opossums, this photo is Pookie, she was a 4-year-old ambassador opossum I once kept. Her diet was a mix of dry Purina Cat Chow, vegetables and diced fruit. One of the greatest challenges in keeping will mammals is preventing obesity and boredom. In the wild, animals burn most of their calories in their constant search for food. That does not occur in captive situations. Completely off-topic…… female American opossums are likely to live considerably longer when they have been spayed and perhaps male opossums have less prostate problems when neutered. You can read about how those procedures are performed here.

How Do McDonald’s Parking Lot Blackbirds, Sparrows And Pigeons Survive On Fries, Grease And Onion Rings?

The bird in my illustration is a great-tailed grackle. The males are iridescent black, the females brownish. They are not related to crows. Grackles are quite intelligent, highly adaptable and have become a pest as they relentlessly advance their range northward from the Mexican border. Leaving our Home Depot I noticed a rustling in the entrance trash can. A moment later, a female grackle poked its head out of the lid and flew away with a french fry. That caused me to wonder how a bird could appear perfectly healthy living on a diet of fat-fried potatoes.

Unlike most songbirds, grackles are known for their behavioral flexibility. In their random explorations, they quickly realize when a certain behavior gives them a new access to food. (ask me for Grackle Logan2016.pdf) Over a relatively short period of time, they have learned that the Golden Arches and similar fast food restaurants with outside eating areas provide them with abundant food. Until fast food dining arrived, a grackle’s diet was composed of insects, seeds, berries lizards and fruit. So, until recently, it consumed a diet rich in protein, calcium, and vitamins. Fast food fries are about 25% dry matter, of which about 80% carbohydrates and 3.4% protein. Once peeled, they have no vitamin A, no vitamin B-12, no vitamin E, no vitamin D-3, and only tiny amounts of calcium, thiamine, niacin, vitamin B-6, B-5 and folate. As served, they are high in salt and grease. The vegetable oils used to fry the chips do, however, supply vitamin E. So how do fast food grackles survive?

I believe they survive because the grackles you see at McDonald’s are not spending their entire day there. The smart ones leave now and then to forage elsewhere, while other grackles take their place. Agricultural scientists put collars on common grackles to track their daily feeding movements at the Texas/Oklahoma border. They found that a grackle’s feeding areas ranged from 10.9-24.4 miles. The average feeding area of each grackle was 125.6 square miles. (ask me for GrackleBray1979.pdf)

You Can Purchase The Mazuri Songbird Diet™ In Powder Form As Your Major Ingredient, Or You Can Rely On Purina Friskies Shreds™ As Your Major Ingredient

You Can Purchase The Mazuri Songbird Diet™ In Powder Form As Your Major Ingredient, Or You Can Rely On Purina Friskies Shreds™ As Your Major Ingredient

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that you see displayed on this webpage also helps me pay the costs of keeping these articles on the Web. Best wishes, Ron Hines.

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that you see displayed on this webpage also helps me pay the costs of keeping these articles on the Web. Best wishes, Ron Hines.