A Wildlife Rehabilitator’s Guide To Medications

Ron Hines DVM PhD

**********************************************

Topical Antiseptics

Most wildlife rehabilitators would probably not call antiseptics medications. I mentioned many of the same products on my webpage on sanitation. Wounded wildlife will arrive with all sorts of injuries and the majority of them don’t need medications. Their wounds are superficial, they just in need lots of good nursing care, a good diet, rest and time to heal. Wildlife are remarkably resistant to infection when wounds are superficial. When they are deep or when they are contaminated with dirt or when bone or organs are exposed it is a very different matter.

I clean superficial wounds with a gauze wipe or Q-tip dipped in diluted organic iodine/Povidine scrub. The iodine scrub product has detergent in it as well as organic iodine. It also contains glycerin to prevent skin dryness. Iodine scrub is the same product surgeons, nurses and veterinarians use on their hands and forearms before surgery. When I apply it to animals, once the traumatized area is clean, any wounds that are not deep get swabbed with straight povone iodine solution. You can purchase both products at WalMart or your neighborhood pharmacy. These organic iodine products are more effective in destroying surface bacteria than alternatives like chlorhexidine. They are also less irritating and inflammatory than chlorhexidine or alcohol. My second choice is 3% hydrogen peroxide. When birds and small mammals are brought to me and the words “Cat Brought or Found…..” comes up in conversation, I always administer an injection of cefazolin &/or enrofloxacin as well. That is because small tooth punctures made by cats can easily remain unnoticed. The teeth of cats carry many pathogenic bacteria. Animals can come in just looking dazed, only to die of septicemia a short time later. You can read about those antibiotics and others farther down this page.

Topical Antibiotics

I mentioned that wildlife are quite resistant to infections once superficial wounds have been cleaned. But sometimes woulds and punctures are deeper. In those cases I generally flush them out with the nitrofurazone water-soluble ointment that you see in the image above. I dilute it with sterile saline, draw the mixture up in a syringe with a catheter tip and gently flush out the wound several times. Then I pat it dry with gauze sponges and cover the area with a thin film of the ointment. I used to purchase it as a dry powder puffer that you see in the image. Covetrus, my drug supply house no longer carries that product. The Farnam puffer to the far right also contains organic iodine. But it also contains other ingredients intended to prevent infection and keep moist areas from oozing fluid. It is designed for livestock and is most often used on barbwire slashes, hoof and fight injuries. Never use products like that where they can become trapped within during healing. I find it useful in treating cracked tortoise scutes in dorsal areas that pool fluid and pus that prevent healing.

When you are flushing wing injuries near the shoulder of birds, keep in mind that the bone is hollow and communicates with the bird’s air sacs and lungs (a pneumatic bone). (read here) A jet of rinse can easily drown the bird if that bone (the humerus) was fractured as it was in this unfortunate harris hawk, shot with an air rifle.

Oral Antibiotics

I do not utilize a lot of oral antibiotics in caring for wildlife. The majority of adult animals that come to me have suffered wounds of various sorts and are quite difficult to pill. Most antibiotics are bitter. I know because I taste all of them before I attempt to use them in wildlife. One exception is pediatric Clavamox powder, which I reconsititute in as little water as possible or just sprinkle the powdered product on the animals food and observe it it eats it. Often, the tail end of a portion of raw chicken can be dipped in Clavamox powder and the unmedicated portion placed in the mouth or nearest the animal. When it gets to the powder and its taste, it is less likely to spit it out than if it sampled the medicated end first.

I rely much more on short-term antibiotic injections for trauma cases. Then I know exactly how much they received.

Clavamox®

When I do feel that an oral antibiotic is required, I most commonly give amoxicillin combined with clavulanic acid. The name brand veterinary product is Clavamox®, the name brand human equivalent is Augmentin®. Both are available as generic equivalents. The avian dose is 125 mg/kg orally twice a day for 5-7 days. Opossums: 20 mg/Kg twice a day. Squirrels 30 mg/Kg twice a day. Clavamox® and all antibiotics similar to penicillin can be highly toxic to grass and plant-eating animals that rely on the ‘good” bacteria in their digestive systems (rumen or cecum) to digest the cellulose in their foods. Species such as deer, rabbits, porcupines, beavers, and woodchucks.

Potentiated Sulfa Drugs such as Trimethoprim Sulfa

Coccidiosis is a rather common malady that wildlife rehabilitators encounter. It is much less of a problem likely to cause symptoms in the wild where animals are not concentrated in small areas as they are in crowded rehab and zoo settings. Diarrhea is the most obvious sign. For that, I give one of the sulfa-drug group, sulfadimethoxine ( Albon®) or trimethoprim/sulfadiazine ( Tribrissen®, Equisul-SDT®). & trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (generic Bactrim®) is equally effective. The problem is that both taste bad and both must be given for many days to be effective. I believe that the most common sulfadimethoxine dose used in birds is 25-50 mg/kg once or twice a day orally for 3-7 days. But others say 16-24 mg/kg twice a day. To treat coccidiosis in carnivorous mammals and ruminants, 50 mg/kg/day initially and then about half that dose for another 10 days. A similar dose has been effective in rabbits and rodents. But it takes a longer treatment time to clear them of coccidia. Tribrissen® has been used at 40 mg/kg twice a day in birds. In rabbits and rodents at a similar dose and at 15-30 mg/kg in other wild mammals. Animals receiving either of these drugs need to consume plenty of fluids to keep the drugs from crystallizing in their kidneys. It is common to find a few coccidia cysts in the stool of healthy animals. That is not reason enough to treat them.

All sulfa drugs have the potential to cause urinary tract “stones” (calculi) when animals are dehydrated and/or do not consume plenty of water. Little, if anything is known as to potential side effects of sulf drugs in wildlife. But skin inflammations and decreased thyroid gland function and skin reactions due to this class of drugs have occasionally been reported in dogs and people. (read here)

Ampicillin Or Amoxicillin

Because both of these drugs are also in the penicillin family, both amoxicillin and ampicillin are highly likely to be toxic to grass and plant-eating animals that rely on the “good” bacteria in their digestive systems (rumen or cecum) to digest the cellulose in their food. Both drugs are inexpensive and readily available. And both have gone out of favor in human medicine because so many bacteria have become resistant to them. But wildlife are unlikely to naturally harbor MRSA+ or other antibiotic-resistant bacteria. So perhaps for things like a salmonella infection they might be helpful. The suggested dose of amoxicillin is the same as for Clavamox. Ampicillin can be given to rats, mice, squirrels, raccoons and opossums at at 44-66 mg/lb (20-30 mg/kg). Larger mammals at the same dose suggested for dogs and cats ( 5-10 mg/lb / 11-22 mg/kg) three times a day. Again, avoid giving this drug to rabbits and other wildlife that primarily eat grass and plants (herbivores). Fowler’s Zoo Medicine, an older textbook, suggests that birds receive amoxicillin at 150-150-175 mg/kg two or three times a day or ampicillin at 100-200 mg/kg two to four times a day. So you see, veterinary drug dose suggestions for wildlife fly by the seat of their pants.

Cephalexin

Cephalexin (aka cefalexin, Keflex®) is another antibiotic within the cephalosporin class of drugs. It is similar enough to ampicillin and amoxicillin that people allergic to those penicillin-class drugs are often allergic to cephalexin as well. However antibiotics allergies are not a problem in wildlife. Cephalexin is safe to use in rats, mice, bats, squirrels, raccoons opossums, bobcats, wolves and foxes at 48-132 mg/lb / 22-60 mg/kg 2-4 times a day. The suggested dose in birds is 110-220 mg/lb / 50-100 mg/kg every 4-8 hours. That is because of the higher metabolic rate of birds. The human dose suggested for mild infection is 25-50 mg/kg, given twice a day. But for severe infections is the same as the avian dose, given for 7-14 days.

The two most common reasons for giving wildlife metronidazole are diarrhea and, in hawks, doves and pigeons, trichomoniasis. There is more about all that on this page. There is really no agreement as to what a proper dose of metronidazole should be or how long to give it. But the metronidazole dose most wildlife rehabilitators use is between 15-25 mg/kg (~7-11 mg/lb) given once or more commonly twice a day for 3-7 days. When treating thrush or trichomoniasis in birds, some suggest 10-30 mg/kg orally twice a day for 5-10 days. Once-a-day doses are generally a bit larger. There is a warning that small “finch”-type birds do not handle metronidazole well. The usual dose in raccoons is the same as the one for dogs and cats, 5-20 mg/kg divided into a morning and evening portion for about 5 days.

I always keep some doxycycline capsules around. For many years at my animal hospital, I used it only to treat psittacosis (parrot fever) in parrots and as part of my heartworm treatment plan for dogs. The suggested dose for all carnivorous mammals is 5-10 mg/kg twice a day. For rabbits and rodents 2.5-5 mg/kg twice a day. For birds, 25-50 mg/kg once or even twice a day. Twice-a-day drug doses are often given at the lower end of the spread.

Doxycycline is one of the few drugs that is effective in treating the many wildlife diseases that ticks carry. Some of those tick-transmitted diseases are caused by bacteria called spirochaetes. The unfortunate skin & bones bobcat kitten in the photo above was covered in ticks. The organism that causes Lyme disease is also a spirochaete. So is urine-transmitted leptospirosis. Doxycycline is usually also effective against the many other diseases transmitted by ticks in the ehrlichia group. One in that group affects white-tailed deer, coyotes, raccoons, fox and dogs. (read here) Doxycycline is also effective against many wildlife diseases that do not need ticks to pass them on (to vector them). Diseases like leptospirosis when carried by raccoons. The typhus group, of bacteria as seen in opossums, and flying squirrels. Brucellosis, as seen in bison and elk responds to doxycycline – particularly when a second antibiotic is added. Many of the nematode parasites that occur in the bodies of wildlife rely on a specific group of bacteria, wolbachia, to thrive. Doxycycline kills wolbachia as well.

So when wildlife come to you in poor general health, weak or anemic and infested with ticks, sucking lice or fleas, you might consider doxycycline as your best choice in antibiotics along with TLC and parasite control.

Injectable Antibiotics

Cefazolin and Enrofloxacin (Batryl®) are the front-line injectable antibiotics I use in wildlife. Both are economical and both attack a large number of different bacteria in the same way ( they are bactericidal ). So they complement each other in critical situations when animals are at “death’s door” and you do not know which bacteria are the likely culprits – Like this dove that came in after being mauled by a cat:

Human physicians are more likely to send wound swabs to a laboratory to have the bacteria identified and tested as to which antibiotics are most appropriate to give. Veterinarians are more likely to prescribe their favorite antibiotics and reserve bacterial identification for only the patients that fail to improve. Wildlife rehabilitators rarely have the financial resources to utilize diagnostic laboratories like the Cornell Lab or VCA/Antech. Besides, it takes critical time that the creature may not have before results are available. Using two antibiotic at a time increases the likelihood that bacteria causing a problem will be destroyed by one or the other medication.

I also add injectable cefazolin, along with nitrofurazone ,to the sterile saline I use to irrigate and clean contaminated leg or wing fractures in wildlife. Read about those procedures in birds here and here. Enrofloxacin and many other antibiotics are too irritating to tissue to be included in irrigating solutions To read more about the common bacteria that invade broken wings and legs and the antibiotics they are most sensitive to, ask me for Tardon2021.

What Injectable Antibiotic Doses Do You Give?

Cefazolin

I aim for 100 mg/kg (45 mg/lb). I purchase 1-gram vials of sterile cefazolin powder intended one-time human use after laparoscopic or fluoroscopic procedures. Normally, physicians rehydrated the powder in the glass vial with sterile water, the entire contents of the vial is then injected and the glass vial is discarded. Very few wild animals in need of antibiot come to me require a 1 gram dose. A morning dove, for example, weights about 128 grams. It would be very uneconomical for you to discard over 98% of the vial’s contents of you rehydrated it all at once. Cefazolin is only stable for 24 hours at room temperature. But if I carefully pry and peal the aluminum cap from the rubber stopper that caps the glass vial, with small wire snipping pliars, the rubber stopper can be removed with a cigarette-lighter-flamed hemostat or forceps. Then I take a flamed, but cooled, spatula and remove the approximate amount of powder I desire. In animals that weigh less than three pounds, the rear cap of a U-40 insulin syringe serves as my sterile mixing cup for the powder on the spatula. I tap the powder into the rear cap, being careful not to contaminate the contents. Then I add a sterile water drawn up the 15th mark on a U-40 syringe and add that to the U-40 syringe cap. In and out action on the syringe dissolves the powder and the entire contents fit back into the U-40 syringe. For larger animals, the clear plastic wrapper of a 3 ml syringe with a 23 gauge needle serves equally well as the sterile container for the same procedure or the end cap of a 5 cc syringe container. All those products were sterilized by radiation. You can enlarge this photo just above to see how its done:

There isn’t much information as to what a proper dose of cefazolin should be in wildlife. A suggested dose for dogs and cats is 20 mg/Kg. A suggested dose for all carnivores is 10-30 mg/kg three times a day. Since I do not weigh out the powder, my doses are only approximations. No matter what the dose you decide on, when you are dealing with infection such as cat bites and deep contaminated wounds, the dose needs to be given at least twice a day and preferably three times a day. Cefazolin only persisted in effective concentrations in the animal’s bloodstream for about four hours. (read here & here) In rats, an acceptable dose is 30-120 mg/kg with the higher dose giving better results. (read here) It is quite common for small animal species that have high metabolic rates to require more medication per pound/Kg of weight than larger animals. Studies also indicate that cefazolin might be more beneficial when you inject it near the site of the wound you are treated. (read here) I’ll bring it up again: This drug, being somewhat similar to the penicillins, is not safe to give to plant-eating animals that rely on the “good” bacteria in their digestive systems (rumen or cecum) to digest the cellulose in their foods = Species such as deer, rabbits, porcupines, beavers, and woodchucks.

Enrofloxacin

Enrofloxacin kills the same group of bacteria that ciprofloxacin (Cipro) does. In fact, in most animals enrofloxacin is converted into ciprofloxacin within their bodies. We know that in cats enrofloxacin is not absorbed nearly as well when given orally as it is when it is given by injection. For my practice, I buy the 2.27% (22.7 mg/ml) generic Enroflox® injectable solution marketed for dogs.The suggested enrofloxacin dose for dogs is 2.5 mg/kg up to twice a day. Although not labeled in the USA for use in cats, veterinarians use it in cats at that same dose. Others suggest double those doses in life threatening infections. In raccoons, some give enrofloxacin at 5 mg/kg without noticeable side effects. In rabbits 5 mg/kg every 12 hours for 14 days is said to have effectively cured snuffles. I have never given enrofloxacin to rabbits. Be quite cautious about giving any antibiotics to rabbits. As I keep harping on, they rely on the “good” bacteria in their cecum for their nutrition. (read here) The suggested intramuscular dose of enrofloxacin for birds is 7.5-15 mg/kg twice a day with the high-end dose reserved for the smaller bird species. I never treat birds with enrofloxacin for more than a few days. That is because as I mentioned, the drug suppresses protective bacteria as well as the bad ones and with time that can lead to a Candida yeast infection. You are also much more likely to see side effect from enrofloxacin if you administer it to animals while they are dehydrated. (ask me for Herrenstien2000) My avian dose of enrofloxacin is 10 mg/kg or 1 mg/100 gram bird. Others give it as high as 20 mg/kg. That equals about 4 of the smallest marks on a U-40 insulin syringe. Enrofloxacin is very irritating to tissue (can cause tissue necrosis). I always draw at least five times the volume of sterile water into my syringe to dilute the drug before I inject it. Some even dilute it ten to one when injecting songbirds. My small mammal dose is 5 mg/kg twice a day. I also depress the syringe plunger very slowly and administer the drug intramuscularly in multiple locations in the breast and thigh of birds and in the muscles of the upper front section of the rear leg of mammals. Do not make injection in the rear of an animal’s thighs because the sciatic nerve passes there. In early studies, enrofloxacin was found on occasion to be associated with joint erosions in fast-growing puppies. That did not occur in kittens. What effects enrofloxacin might have on the joints of growing wildlife is unknown. I have administered this drug countless times since it came on the market. I have never seen it cause joint problems in young wildlife, cats or dogs.

Some suggest that enrofloxacin injections be given subcutaneously (SC) to songbirds. Feathers make that next to impossible. And even if plucked, birds have little or no subcutaneous space in which to deposit an injected solution. It is also quite easy when inserting the needle at the low angle required for a SC injection to poke through and have the solution end up on the skin rather than under it. So I give those injections into the muscles of the forward side of the upper thigh. I give the diluted product very slowly and I hold pressure with my index finger on the point where the needle inserted so nothing leaks back.

Convenia®

Convenia® (cefovecin) is in the same family of antibiotics as cephalexin. However it has the great advantage of a single subcutaneous injection lasting for 7-14 days. That minimizes capture and injection stress in fearful wildlife. The canine and feline dose recommended is 3.6 mg/lb (8 mg/kg). I do not use it, but Convenia® has successfully been given to raccoons at a dose of 8 mg/kg subcutaneously – and repeated in 10 days when required. In one study it was given intramuscularly to birds. But later studies found that the drug did not persist in the bird’s body nearly as long as they had expected. In dogs the drug often increases blood liver enzyme levels. (ALT & GGT) so be cautious using this drug, particularly when the animal might already have liver issues.

Metronidazole And Similar Medications

Metronidazole was first marketed as Flagyl®. It is a drug that kills protozoa, microscopic one-celled organisms. It will kill a few bacteria (anaerobes ) too, but none that are typically a problem in wildlife. Metronidazole also appears to have positive effects in animals with diarrhea – even when the cause of the diarrhea is not due to an organism the drug is known to destroy. (read here) The most common reasons that wildlife rehabilitators give their animals metronidazole is to treat trichomonas disease in birds and diarrhea in raccoons.

In birds, an accepted dose of metronidazole is 10-30 mg/kg orally twice a day for five to ten days – with the warning that “finch”-type birds do not handle the medication well. However a group with extensive experience administering metronidazole to raptors gives their patients metronidazole at up to 100 mg/kg per day orally for 3 days. As another example, the Bush Gardens rehab center in Florida’s metronidazole dose for raptors is 50 mg/kg, once a day orally for 5 days. So there is no agreement as to what a proper dose of metronidazole should be or how long it should be given. Ask me for Samour2003pdf & Spriggs2020.

Trichomoniasis (called by some trichomonosis) is most often seen in doves, pigeons and the raptors that prey on them – particularly cooper’s hawks. Birds near large urban centers seem particularly susceptible – probably because of the presence of large flocks of infected urban pigeons and the abundance of bird feeders and bird baths that draw abnormally large congregations of birds together for cross-infection. Falconers call trichomoniasis “Frounce”. Because the disease has plagued their birds for centuries, they have learned to remove the heads of pigeons and doves before they offer them to their raptors to eat. I am uncertain if there is any benefit to doing that because trichomonads are not confined to those areas of the bird’s body but perhaps it is helpful. Typical signs you might see in doves, pigeons and raptors are whitish yellow, slightly raised spots in the mouth (plaques, canker) with a consistency of cheese, gaping (open mouth), gasping, refusal to eat, slow crop emptying, and vomiting (regurgitation). The only way to make a definite diagnosis is to see the wiggling organisms under a microscope. Candida (“sour crop” or thrush ) fungus, aspergillosis (another fungus) or a vitamin A deficiency can all be mistaken for trichomoniasis. Since all of these diseases rely on a bird being under stress, several of these organisms can be present at the same time. Metronidazole is only beneficial when trichomonas or some other protozoa is one of the participants in the group. Another common cause for trichomonas overgrowth is giving other antibiotics or corticosteroids to a bird or mammal that did not require them. Metronidazole is not helpful in treating Candida. That needs to be treated with an anti-fungal medication such as nystatin, itraconazole or fluconazole. Aspergillus fungus is never successfully treated – at least not by me. There is also some evidence that dilute boric acid is helpful in killing trichomonads. It has been found that young raptor nestlings – the most susceptible to trichomonas disease – have a less acidic mouth than older nestlings or adults. (read here) topical boric acid helps cure human trichomonas disease (read here) ; but I do not know of it having been tried in birds. If you do let me know.

Diarrhea can be a major problem when raising large numbers of orphan raccoon kits. When it is, the most likely cause is one of the parvoviruses – the one specific to raccoons, the parvovirus of dogs or the parvovirus of cats. In urban raccoons, it is the dog parvovirus they are most likely to encounter. Metronidazole has no effect on parvovirus. When it seems helpful to those raccoons, it is either because the parvovirus has caused an overgrowth of a protozoa such as giardia or because of metronidazole’s unexplained “calming” effect on the intestinal tract no mater what the underlying cause seems to be. The usual dose in raccoons is the same as the one for dogs and cats, 5-20 mg/kg divided into a morning and evening portion for about 5 days. Some raccoon rehabbers give considerably higher doses. As with birds, there is little agreement as to what a proper dose of metronidazole should be. You need to combine that with the same treatments provided to parvo-infected dogs. ( read here ) Young ambassador raccoons need a series of Merial/Boehringer Ingelheim’s Recombitek C3/C4 or Merck’s Nobivac’s Canine 1-DAPPv and an Emrab-3 rabies shot at 16 wks (if that is legal to do in your state).

There are other alternatives to metronidazole. One is carnidazole (Spartrix®) and the other is ronidazole (Ronex®). I have no experience using either of them, but one published dose for carnidazole was 30 mg/kg given once orally. Another suggested the same dose once a day for 2-3 days. Both are marketed for pigeons and falconer raptors. Since I know of no reports of trichomonas having become resistant to metronidazole, the only advantage of these newer and more expensive products might be a more pleasant taste. Metronidazole is exceedingly bitter and metallic in taste. Chewy and and Wedgewood sells flavored metronidazole in liquid form. But neither of their pharmacists could tell me which of their flavors, if any, might be acceptable to birds or raccoons.

Fluids For Injections

By the time wildlife reach you, a good portion of them will be dehydrated. An assessment for dehydration is one of the first things I do. Dehydrated wildlife tend to be inactive and apathetic. In mammals, the classic diagnostic is a finger pinch. If you elevate the skin with a pinch and then let go, dehydrated skin does not spring back quickly (loss of elasticity). If you look at the animals eyes, they eyeballs are slightly set back and the eyelids not fully open. Of course, a lot of animals with severe health problems other than primary dehydration have sunken eyes due to poor circulation. Their nose might by dry, their gums sticky. When it comes to birds, skin pinch doesn’t work. What I look for there is the characteristic wrinkly skin and increased visibility of the tiny blood vessels that lay just below their translucent skin. Stools that would normally have the consistency of an egg cracked in a cup are much stiffer in dehydrated birds – if they pass any stool at all. Once you rehydrate them, that should be the first thing they do and you can judge your success in rehydrating them based on that stools consistency – the more liquid they are the better. Dehydrated birds do not have sunken eyes because the eyeballs surrounding their corneas contain bony ossicles.

Giving fluids by mouth to semi-comatose animals is always dangerous. It needs to be done no more than a drop at a time to tiny foundlings. Even then, it may enter the lungs. Even when to reaches the stomach, animals near death’s door don’t absorb it readily. Their circulatory system and blood pressure is too low. Normal injectable saline (PSS) is 0.9% salt, the rest being water. I tend to give dehydrated animals 0.45% sterile saline in 5% dextrose. That is because they do not lack salt in their bodies but probably are hypoglycemic. They only lack water and sugar calories. Adding more salt can be delirious. .45% saline in 5% dextrose is used in hospitals in the neonatal intensive care ward, primarily in babies that are dehydrated due to diarrhea. It is given to me by my local hospital when it is short-dated. The Baxter Healthcare code on the 250ml package in front of me is 6E1072 NDC 0338-6308-02. The presence of dextrose makes these bags subject to bacterial contamination if you withdraw from the bag on multiple occasions. So I use a 60 ml syringe and transfer them contents to 4 ml sterile urine collection tubes and store them in the refrigerator top shelf. You can see those yellow-top, no additive, tubes at the center of the second photo.

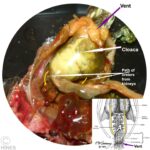

Dehydrated birds are subject to cloacal impaction (see the 3rd photo above) That in itself can be fatal as it was to the starling chick in the third photo that was fed a diet that was too firm. They were attempting to raise two baby starlings to teach them to talk. They were tube feeding the birds a diet that was not moist enough. By the time they brought them to me, I was able to rehydrate one chick with injections – but too late to help the other. Mammals like us pass the byproducts of protein metabolism as urea. Urea is quite soluble in water. But birds and reptiles pass their byproducts of protein metabolism as uric acid. Uric acid is much less soluble than urea. You know how stubborn it is to get off of bird cage floors. So in dehydrated birds it forms blockages in the cloaca that were, it the starling’s case, fatal.

As I mentioned regarding antibiotic injections, extreme care needs to be taken so as not to tear the fragile skin of small birds or to go under the skin with your hypodermic needle and inadvertently out the other side. If you have the patience, you can give fluids intramuscularly in the leg or breast very very slowly after you draw back on the syringe to be sure you are not in a vein or artery. You also never want to give fluids into one of the air sacs shown in the second photo because that can instantly drown a bird with the fluid exiting its mouth as it gasps.

Ketamine & Anesthesia

Whenever you see the you know that the DEA will be looking over your shoulder. That means lots and lots of paperwork, federal fees for most of us, and a storage container (like this safe) to meet their requirements. Ketamine and similar medications with lower abuse potential are not C-II, they are C-III. and diazepam and similar medications are in C-IV. So you will most likely need a veterinarian involved in the use of any DEA-controlled product. Never administer anesthetics or tranquilizers to wildlife until their hydration, heart and respiratory functions have all been stabilized. Animals that are underweight due to starvation are also at much greater risk.

There are as many injectable wildlife anesthetic recipes and mixtures as their are cooking recipes. But ketamine is still my anesthetic of choice for small mammals and birds. It works well for me tigers as well (I wait for their tail to be reachable through their cage bars and give their first injection there). In my opinion it still the safest injectable anesthetic available. Pediatric surgeons still frequently administer ketamine as well. (read here) Ketamine works by unlinking portions of the animal’s brain (a dissociative anesthetic). That blocks the sensation of pain and causes sedation at low doses, or unconsciousness directly proportional to the dose of the drug that is given. Ketamine does not depress respiration and blood pressure as true narcotics or gas anesthesia do . It’s primary drawback over other anesthetic options is that ketamine does not cause muscle relaxation. Used alone, te opposite is likely to occur. So for orthopedic surgery, a second medication to help relax muscles, diazepam, is usually added (but never in the same syringe). Ketamine can also be given for restraint and manipulation in the process of placing wildlife on a gas anesthetic such as isoflurane or sevoflurane (induction). I rarely utilize those gases because they are unhealthy for human beings to repeatedly inhale. (read here , here & here) You should avoid being exposed to them too. A second reason that anesthetic gas administration is not appropriate for me is that I no longer have a veterinary nurse, experienced in monitoring the animal’s depth of anesthesia. In many surgeries, success is half due to the expertise of the surgeon and half to the expertise of the anesthesiologist. (read here) With injectable medications I have control of both.

In felines, a dose of 11 mg/kg (5 mg/lb) is sufficient for sedation and restraint. Doses in the 20 to 30 mg/kg (10 to 15 mg/lb) produce anesthesia that is usually sufficient for diagnostic and surgical procedures that do not require skeletal muscle relaxation. When that is an issue, a separate diazepam injection is required. An accepted avian sedation dose is 5-15 mg/kg. For surgical anesthesia a dose of 20-40 mg/kg is more likely to be used. Every animal is unique. I always begin with a conservative small dose injection, observe the effect, and only give a supplemental doses when required. Long procedures require repeated injections. But never as much as the initial one. Some also give atropine sulfate @ 0.04 mg/kg (0.02 mg/lb) to control salivation. Ketamine is less suitable for use in canines. Muscle rigidity and salivation are more of a problem in canines. Years ago, I utilized acepromazine to aid in muscle relaxation. The dose I used at that time, in addition to ketamine, was 0.1 mg/ kg. Ketamine is acidic. So it burns when given intramuscularly unless you dilute it before injection. My approximate ketamine dose for pigeons is 10mg/45 grams, for hawks is 80 mg/454 grams, for screech owls 10 mg/100 grams. My Chicken/duck dose is approximately 15-20 mg/kg. My ferret dose is 1 mg/100 grams. My rabbit dose is 20-50 mg/ kg. I NEVER GIVE THESE DOSES ALL AT ONCE. It is much safer to step dose animals – give a portion of the theoretical dose, observe the results, repeat as required based on the depth of anesthesia achieved.

Ketamine can also been supplemented with midazolam (Versed®) as an alternative to diazepam. Neither should be added to the same syringe containing ketamine. Others add xylazine (Rompun®), a drug I avoid administering whenever I can because of its negative effects on heartbeat and respiration. Others combine ketamine with medetomidine (Domitor®).

It is never wise to anesthetize animals shortly after they have eaten. That increases the chance that they will regurgitate the food and, in the process inhale some (aspiration pneumonia). Administering atropine at 0.02 mg/lb reduces that likelihood.

Wildlife waking up after receiving ketamine are highly sensitive to noise and other stimuli. I always place them in a padded environment in a darkened room free from other animals and human traffic to eliminate or minimize that.

Other Anesthetics That The DEA Does Not Currently Regulate

Isoflurane

Isoflurane and sevoflurane are excellent aesthetics for wildlife. However, as I mentioned before, it is unwise to be exposed to either of them frequently. Both provide muscle relaxation far superior to unsupplemented ketamine and all species wake up very rapidly when either gas is discontinued. So hyperexcitability on recovery is much less likely to occur that when ketamine was the primary anesthetic agent. Unfortunately, the primary use for isoflurane in wildlife rehabilitation is as a humane method of euthanasia. Just because the DEA does not regulate those two drugs does not mean that exposure to their fumes cannot be addictive. Read about one case here. I know of other cases among my friends.

Lidocaine

Lidocaine blocks pain by interfering with pain singles to the brain. When one is knowledgeable as to the locations of the major nerves of the animal’s legs or wing, appropriately-placed lidocaine injections will also make the area completely insensitive to pain. I occasionally use that technique to remove imbedded fish hooks. However lidocaine and drug similar to it do nothing to decrease the terror that adult and not yet mature wild animals experience when being handled or in close proximity to humans. I do occasionally perform supplemental lidocaine blocks for wing and leg injury repair when I feel that administering additional general anesthetic or tranquilizers would be a risk to the animal’s life.

Propofol

Propofol is a very effective anesthetic. As of this writing, it’s purchase is not yet controlled by the DEA – although I am told that they are thinking about it. Propofol is best administered intravenously, through a catheter as a slow drip during surgery. An accepted dose for carnivores is 0.1–0.6 mg/kg/min and for rabbits, 1.2–1.3 mg/kg/min. However this drug can abruptly cause animals to stop breathing. The effects wear off very rapidly, so if one rhythmically presses on the animal’s chest they usually regain their ability to breath in a minute or two. I have never attempted surgery using propofol. But I did purchase some out of curiosity. I gave two ~26 gram English sparrows the standard 10 mg/ml propofol at a dose of 0.15-0.2 ml. But first I diluting the propofol dose in the U-40 insulin syringe to 0.3 ml with PSS. I injected it intramuscularly with the tip of the needle just touching the bird’s sternum. The sparrows were anesthetized for approximately 2 minutes. Then they abruptly awoke and flew off.

ORA-Plus

The image above shows the three common suspending liquids (vehicles) that pharmacists use to make custom medications for people. There are others; but these are the only three I know of that are unflavored. All three can be diluted with an equal volume of flavored liquid such as a meat broth or sweet syrup and will prevent the powdered medicine(s) and/or vitamins that you add from settling to the bottom. My only experience is with the ORA-Plus brand but all three have almost identical ingredients: powdered cellulose, xanthan gum, carrageenan and an anti-foaming agent (dimethicone or simethicone). All have citric acid added to keep the final product acidic. that is because medications and other ingredients that are suspended in acidic solutions tend to last longer. Despite that being the case, I would discard the batch you made after 10 days – even if you kept it in the refrigerator.

Pain Control Medications

The state and federal agencies that license wildlife rehabilitators in America pay little attention to the pain that injured wildlife experience. They prefer to ignore that because making the medications that lessen pain easily available to wildlife rehabilitators presents them with regulatory problems. When confronted with uncomfortable questions regarding pain and a wild animals fate, their response is “Let Nature take its course”. If they had the slightest empathy for wildlife, they would have outlawed bow hunting for all but Native Americans many years ago.

Nature designed all wild animals to hide evidence of their pain so as not to be recognized as easy prey by their predators. Animals domesticated by humans are less likely to do that. In wild animals, signs that suggest pain include any abnormal posture, lameness or reluctance to move. Any behavior abnormal to the species is another. That could be a lack of vocalization, digging, pawing perching and the like. Reduced interest in grooming or preening is another common sign as is a reluctance to eat.

My two choices in pain control medications are injectable butorphanol (Torbugesic®) and meloxicam (Metacam®) Meloxicam is an NSAID. All felines are particularly sensitive to NSAIDs. Birds can be too, particularly when these drugs are given for long periods. When side effects occur, they are usually related to kidney damage. (read here) Dehydration in all animal species also make side effects more likely.

Butorphanol

Butorphanol is a narcotic. The pain-relieving abilities of butorphanol in all mammal and avian species are well documented. It is sold to veterinarians to relieve the pain of colic in horses as well as to minimize pain after birthing. The suggested dose in horses is 0.1 mg/kg given IV up to every 3-4 hours for up to 2 days. For humans, it is sold as a nasal spray to eliminate the pain of migraine headaches (Stadol® NS). A published dose of butorphanol for injection in dogs is 0.1 to 1 mg/kg) two to six times per day. For carnivores in general: 0.1–0.5 mg/kg every two to four hours. In rabbits and small rodents: 0.1–0.5 mg/kg every four to six hours. In prairie dogs: 2 mg/kg every four hours. In birds, butorphanol doses given range from 0.5 – 6 mg/kg given intramuscularly up to every six hours. Others suggested 1-3 mg/kg. Some have reported that the drug is toxic to gyrfalcons and owls. When side effects occur in all species, they are usually breathing difficulties and critically low blood pressure – a common effect of all narcotic overdoses.

The main reasons butorphanol is not given more frequently is that the DEA purposely places many obstacles to discourage its use ( ask me for Doss2018 ). The other major drawback is that the drug’s pain-relieving ability is so short acting

Meloxicam

The effectiveness of meloxicam (Metacam®, Mobic®) in alleviating the acute pain of trauma, fractures, accidents or surgery is not nearly as well documented. (read here) Its two main advantages are the opposite of butorphanol’s negatives – meloxicam is not regulated by the DEA and its effects last at least a full day. Meloxicam, like all NSAIDs is, over time, very effective in decreasing inflammation. But studies on its effect on acute pain give erratic results. That is because pain is an exceptionally hard thing to quantify (measure). Blood components are easy to measure, drug blood levels are easy to measure, respiration, temperature and heartbeat are easy to measure – but pain level in animals that can’t talk to us is a very difficult thing to quantify.

The suggested dose of meloxicam for dogs is 0.2 mg/kg given subcutaneously or intravenously the first day and then orally at 0.1 mg/kg once a day. For cats, a single, one-time subcutaneous dose 0.3 mg/kg is suggested. Meloxicam has been given to rodents at 1-2 mg/kg once a day orally or subcutaneously and to rabbits at 1 mg/kg per day orally. Some have doubled the dose in those species and give it every three days.

In birds a meloxicam dose of 2 mg/kg given intramuscularly was found to relieve pain in pigeons with experimental leg fractures. When given at 0.5 mg/kg it had no effect. (read here and here) Others suggest that meloxicam can be given orally at 1.6 mg/kg once a day for up to seven days. (read here) In parrots meloxicam, given intramuscularly at 1 mg/kg every 12 hours for 3 injections was thought to be safe. (read here)

Are There Others?

Yes

A great many other medications have been given or discussed at one time or another in an attempt to decrease pain in injured wildlife. But none of them have ever been proven to be effective. In Tennessee, tramadol was given to bald eagles intravenously at 4 mg/kg and orally at 11 mg/kg. But no attempt was ever made to judge the amount of pain relief it might have produced. (read here) In another study, tramadol, given orally to dogs for 10 days at 5 mg/kg it did not lessen the pain of arthritis. (read here) But when given at the same dose to kestrels it appeared to other authors to provide pain relief. (read here) So perhaps the effectiveness of tramadol might vary greatly between species. Like butorphanol, tramadol is a DEA-controlled medication.

Gabapentin, an anti-seizure medication, is also thought to have pain-relieving effects. In birds, oral doses given range from 10 mg/kg to as high as 80 mg/kg. (read here) In dogs, gabapentin given orally at 10 mg/kg might have had some pain-relieving effects. (read here) A recent study in women found gabapentin ineffective in relieving pelvic pain (read here) Where it does show some promise is in treating chronic neuropathic pain.

Appetite Stimulants

Wildlife rehabilitators all face times when an animal in our care won’t eat. For me, it’s usually an osprey. Or perhaps a swallow, martin or nighthawk – species that in nature only eat on the wing. But occasionally, frightened mammals and those with internal injuries or serious internal disease refuse to eat as well. In all those cases an appetite stimulant hidden in a small treat and given with assistance or by injection might be an option. Or perhaps medications applied to the inner ear such as Mirtaz® or one designed to be given by injection or orally such as diazepam or midazolammight help as a “kick start” to independent eating. The tray in the image above shows some of the veterinary appetite stimulants known to be effective in dogs and/or cats. Not all appetite stimulants that help in dogs and cats are known to work in other species. Capromorelin (Entyce® & Elura®) is the most recently approved appetite stimulant for dogs and cats. Read about that product here and here.

I rely on professor Mans, the wildlife specialist at the Veterinary College, Madison, Wisconsin. He studies appetite stimulation in wildlife in a thoughtful scientific way. If you have a question regarding appetite stimulation in your rehab wildlife, anesthesia techniques, pain control or wildlife medications and diagnostic techniques in general it would be wise for you to contact his group directly. He informed me that in birds, diazepam (Valium®) given intramuscularly by injection was a powerful appetite stimulant in bald eagles and parakeets. They confirmed that midazolam (Versed®), a drug similar to diazepam, was also an effective appetite stimulant in birds. Cyproheptadine (Periactin®) that some veterinarians dispense to dogs and cats that won’t eat did not have much of an appetite-stimulating effect in birds. Nor did mirtazapine at the doses they administered. Mirtazapine was also was associated with regurgitation (vomiting).

Appetite stimulants do not correct the underlying causes of starvation and refusal to eat. You can read about some of those causes here.

Corticosteroids Such As Dexamethasone

Corticosteroids such as dexamethasone also stimulate appetite. However prolonged use can slow healing, increase thirst, raise blood sugar, lower immunity to infections, affect pressure within the eye, weaken bone and suppress adrenal gland function.The suggested dose of dexamethasone for cats and dogs ranges from 0.2 – 6.0 mg/kg. A suggested dose in ruminants is 0.1 – 0.2 mg/kg. Dexamethasone has been administered intramuscularly to chickens at 0.5 – 2 mg/kg for its anti-inflammatory effect. In another trial in poultry the persistence of dexamethasone after an intramuscular injection at 0.3 mg/kg was very short. Only half that amount was still present in the bird’s bodies after 0.7 hours.

Most wildlife rehabilitators including myself receive quite a few songbirds that have been attacked by cats.

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that Google chooses to display on this webpage helps me pay the cost of keeping this article on the Web. As you know, sites like mine that are not designed to make money are getting harder and harder to find. Best wishes, Ron Hines

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that Google chooses to display on this webpage helps me pay the cost of keeping this article on the Web. As you know, sites like mine that are not designed to make money are getting harder and harder to find. Best wishes, Ron Hines