A Wildlife Rehabilitator’s Guide To Cages And Pens

Ron Hines DVM PhD

All Of Dr. Hines’ Other Wildlife Rehab Articles

All Of Dr. Hines’ Other Wildlife Rehab Articles

If you have the financial resources to purchase zoo-quality cages and pens or to have experts build them for you, this article is not for you. Wildlife rehabilitation tends to be a middle class passion of individuals like myself. It consumes more free time and resources than poor people are likely to have or that affluent folks are likely to willingly part with. Although a great need for more wildlife rehabilitators exists throughout the United States, large wildlife rehabilitation centers usually locate on the outskirts of major urban centers. That is not because more wildlife in need or more compassionate people live there. It is because those rehab centers rely on plentiful donations from the surrounding urban population and the greater availability of unpaid volunteers managed by a paid staff. It costs a great deal of money to adequately care for large numbers of sick, injured and orphaned wild creatures. No state or federal entities feel inclined to financially assist you. So I do my best to stretch the modest revenue that the Google ads you see running on this website bring in. These are some of the ways I do it:

Where Should I Put My Cages And Pens?

Adult and near-adult wildlife do not appreciate human contact. And when they do accept it, it invariably handicaps them after their release. So locate your pens and cages as far away from people and pets as possible. There needs to be sufficient distance between individual animal species. Animals are extremely aware of their environment. That is why I have always purchased a small house with a large lot, privacy and animal-friendly neighbors. Here in Texas, our 2 acre lot, shares a fence with the rear portion of a low income trailer park – separated by a 20-foot strip of planted native brush and mesquite.

The noise, smell or view of what wildlife perceive to be a threat or a rival is very stressful. However wildlife you care for will rarely allow you to see outward signs of that stress and fear. Hidden fear interferes with their successful rehabilitation in many ways. It increases their susceptibility to disease and makes current health issues worse. It causes cortisol release. Cortisol increases their blood sugar – a good thing when a fast escape is possible – but with time, high cortisol negatively affects digestion, growth and healing. With time persistently high corticosteroids of all types also lead to mood disorders and depression. (read here) Fear also increases the likelihood of injuries and self-mutilation in the animals you care fore.

Eliminating fear and stress is easy for those not involved in the day-to-day care of wildlife to demand. But it is a very hard thing for hands on people like us to actually accomplish. All your wards need to be fed, cared for, at times restrained and medicated. The best you can hope for is to do those things in the least stressful manner possible without resorting to taming. The tamer an animal becomes, the less likely it will be to survive after release. Contrary to what some people believe, neither imprinting nor tameness are irreversible. That is because genes and conditioning play a large part in animal behavior. The less contact you have with your wards as their release date approaches, the better their chances are that their genetic tendencies to fear and suspicion will reappear. I find that reversion to wildness is remarkably successful when abnormally tame and human-dependent animals are house with human-fearful animals of the same or similar species.

We humans rely primarily on our vision to evaluate environmental threats. So it is natural that we would assume that wildlife of all kinds are just as dependent on what they see and that visual camouflage was their main means of defense. We tend to forget the non-visual camouflages that occur between predators and prey. Some animals have olfactory (sense of smell) capabilities hundreds of times better than ours. The hearing ability of most wildlife are far better than ours and they likely have sensory ways to detect danger and opportunity that have yet to be discovered. For instance, the personality of a raptor or rabbit in one of my small indoor treatment cages is entirely different from the personality of the same raptor and rabbit when moved to a larger outdoor accommodation. (read here )

Ant Problems

In my area of Texas, fire ants are a perpetual problem for free wildlife and to animals in rehab. We treat fire ant mounds when we locate them, however we never locate them all and even when we do they tend to just move a few feet from their original site and continue their destrctive behavior. That is why whenever I can, I construct four post cages to protect the small animals in my care. A 5 inch section on each 4X4 post, buttered with general purpose grease prevents the ants from reaching the rehab animals. I re-apply the grease whenever dead ants, dust and debries again allow the ants to bridge over the grease barrier.

Wildlife Need Their Natural Substrates

Small mammals long for concealment from larger predators. Most have fur that matches the colors of their natural habitat when they freeze motionless. A few others have repeating stripes and blotches that help blur their presence when they are in motion. Even predatory sit and wait raptors use their color schemes to their advantage. Neither prey or predator can be comfortable when they sense that they stand out. Try to match your concealment devices to the species. Burrowers are going to want dark interior boxes, cottontail rabbits clumps of brush, high percher tall cages with tree limbs they can look down from, owls their cage “attic” nooks and crannies. Where water and food containers are placed need to match the animals feeding habits in the wild. Ground feeders are not going to be happy with elevated containers and vice versa.

When it comes to growing birds, foot and leg weakness is often due to perches of the wrong diameter or perches of one continuous diameter. Fresh, frequently replaced branches and natural cage substrates and outdoor living also provide more healthy bacteria than any commercial probiotic pasts or powder.

Deer

Deer do best for me in a slat wood fencing picket enclosures with a corner shade netting placed high enough to be out of their reach. They should have as little human contact as possible. That can be a problem as they tend to attract the attention of volunteers. 6-8 inches of sand substrate with a moderate slope minimizes injury, intestinal parasite buildup, and other sanitation issues. Deer are prone to injure themselves when exposed to sudden noises or unexpected movement. The first photo is a Florida key deer flown to me by USFWS after being hit by a car on Big Pine Key. Treated wood fencing contains copper and arsenic. It needs to be checked regularly for signs of gnawing.

Nestling Feeder Bins From The Dollar Tree

I use lightweight plastic bathroom trash receptacles with several inches of leaf mulch at the bottom shaped into a simulated nest. An appropriately cut piece of 1/2 inch hardware cloth makes a good cover when weighed down with an expired bag of IV fluids. As the birds grow, I move them to an appropriately sized cardboard box – again lined with several inches of leaf mulch. Each container of unfledged youngsters gets a thermometer with my target temperature being ~35 C/95 F.

Everyone Appreciates A Hidden Nook

All animals are terrified when eyes look down at them. A comfortable high hiding place is always an appreciated stress reducer.

Owls Value Their Privacy

Darkness, hearing and seeing without being seen is their thing. The amazing abilities of barn owns and how they successfully hunt rodents by sound alone in zero light. (read here)

More About Flooring, Perches, Bedding And Bumble Foot

I do not keep raptors, waterfowl or other wildlife for long periods of time. For those that do keep “ambassador” birds, bumble foot and aspergillosis are the two most common avian threats. Veterinarians call bumblefoot pododermatitis. In birds, the causes are a lack of flight time, perches that do not vary in diameter, excessive fecal deposits on porous perches, sharp projections, too high a humidity and obesity (excessive body weight). In small mammals, add hard flooring, and poor sanitation. Pododermatitis is a progressive disease with the lower (plantar) surface of the feet first affected. Foot pad swelling and redness occurs first. That progresses to fluid-filled spaces (= vesicles). When they burst, the ulcers that they form quickly become infected. With time that inflammation spreads as high as the animal’s hocks and the bones and joints themselves eventually become involved. Since it is an environmentally-caused disease, antibiotics in themselves are never curative. The center photo above shows a traditional falconer’s perch. It solves the dampness problem and the rope can be replaced at intervals for hygiene. But it lacks a key ingredient – it is all of the same diameter. If you want to read more about bumblefoot in raptors ask me for Diez2020.pdf .

Fighting bumblefoot in amusement parks, zoos and aquarium penguins is a constant battle. Not much less so in waterfowl and sea bird displays with cement bottoms. Display penguins spend ~80-90% of their time standing in their displays; while non-breeding penguins in the wild spend ~75% of their time in the water searching for food. The high humidity of theme park displays as opposed to their wild nesting areas adds to their foot problems. Penguin feet were not designed for the perpetual standing they must endure in captivity.

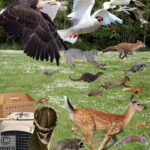

The middle two birds in the photos above are caracaras. I receive a lot of them. They are ground-feeding raptors that never pass up a meal of carrion (a glorified buzzard). Caracaras are always on the lookout for dead animals along our South Texas highways. However as they feed on the roadkill, they often become victims of the next car or truck that passes by. I have had success mending their wings. And because they are ground feeders, their post-surgery flying abilities do not have to be 100% to survive after release.

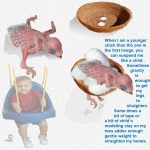

Spraddle Leg

Spraddle leg or “swimmers” is a rather common occurrence in immature birds that are housed on slick surfaces. Occasionally, a similar one-leg problem occurs when a baby’s leg gets tangled in twine that the parents incorporated while constructing their nest. Spraddle leg occasionally occurs in furry mammals as well. Particularly when a well-meaning but uniformed person feeds a diet that is calcium and/or D-3 -deficient to a rapidly growing animal. It can be mended by wildlife rehabilitators using orthopedic devices. You can read about Spraddle leg treatments here. Once an animal of any species nears the end of its growth period it becomes a hard defect to repair. I do so by making strategic cuts through the bone to bring leg portions into better alignment. However results are never 100% successful.

Aggression

Just because two animals are of the same species and of opposite sex does not mean they will get along. The larger female caracara in the photo dominated the male’s access to food so they had to be separated. The same goes for mammals. Pair-bonding is hormone-driven and your matchmaker efforts can be unrewarding or worse.

Transport Taxis

I know it is time consuming and that the little nuts get lost. But the best way to remove wildlife from pet carriers is to unfasten the screws and nuts that hold them together. Better still, if it is not a medical emergency, is to just place the carrier in a spacious cage or flight, leave the carrier door open and have patience.

When Its Time To Release

For all wildlife raising their offspring is very stressful. Not only must they protect their own welfare regarding stuffiest food and avoiding their predators, they must provide their offspring with sufficient food and protection as well. Some call that the parent: offspring conflict as to when to wean their offspring and send them off on their own. Its in the babies best interest to stay with their parents as long as they can. But it’s in the parent’s interest to send them off on their own as quickly as possible. It has been studied most in songbirds because they grow up so fast. You see this conflict in easiest in the jays and parking lot blackbirds with their babies – now as large or larger than they are – chasing their parents and begging for food. They birds you raise are not going to give up their short-order cook willingly either. In one study in songbirds, fledging their offspring as early as possible reduced the average fledglings survival by 13.6%. It’s not quite that simple. Brood size and abundance of food play a great part in parental exhaustion as well. So does the steady drop in the hormone responsible for motherly love – oxytocin and prolactin. So does nest or den location with those unfortunate enough to have chosen a high-stress location or proximity to man more likely to have high corticosteroid levels that influence them to abandon their offspring earlier. ( read here , here and here )

The first two hormones of broodiness and mothering drop at unpredictable rates as the gonads (ovaries & testicles) of all seasonal breeders wither after the breeding season ends (gonadal involution). Some believe that the animal’s thyroid hormone levels (T3) play a part in this as well. (read here) It all relates back to the animals in your care sensing the changing seasons. That is why natural sunshine is so much better for the wild animals in your care than indoor lighting.

So besides the random events that will always occur, those conflicts are what bring orphan animals to you and because it is an advantage to a wildlife animal’s chances of post-release survival, I feed them and protect them considerably longer than their natural parents would – two to four weeks longer for songbirds and raptor and two to four month longer for mammals. Hopefully that will make up for some of the behavior disabilities that invariably occur in all human-raised wildlife. You can see some normal growth curves and fledging times for North American song birds here.

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that Google chooses to display on this webpage helps me pay the cost of keeping this article on the Web. As you know, sites like mine that are not designed to make money are getting harder and harder to find. Best wishes, Ron Hines

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that Google chooses to display on this webpage helps me pay the cost of keeping this article on the Web. As you know, sites like mine that are not designed to make money are getting harder and harder to find. Best wishes, Ron Hines