Ron Hines DVM PhD

Some General Facts About Canine Distemper

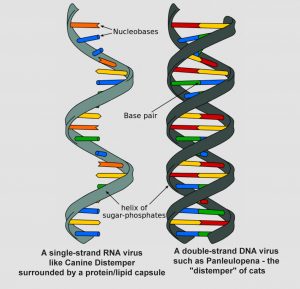

Canine distemper (CDV) is a serious, highly contagious viral disease. Although it can affect many animal species, most think of it as a disease of dogs. The distemper virus of dogs is not related to the “distemper virus” of cats (panleukopenia). Dog distemper is an RNA virus ; cat distemper, on the other hand, is a DNA virus.

Distemper virus affects dogs all over the world. Some suggest that distemper was once only present in the Americas and that it was imported from Peru to Spain in the 17th century. (read here) But others believe the evidence points to the disease moving the other direction. With the coming of the Spaniards, the dog population of Native Americans almost completely disappeared (read here & here)

The distemper virus has a strong affinity for the blood lymphocyte cells that are a critical part of your dog’s immune system. So, lymphocytes are the first cells that the distemper virus destroy. When that occurs, the number of circulating lymphocytes in your dog’s blood drops sharply. (read here) With their immune system crippled, those dogs become more susceptible to secondary bacterial infections.

Very effective, long-lasting, vaccines have made distemper a rare disease in the North America and everywhere in the world where dogs receive distemper vaccinations early in their lives. But canine distemper is still a common cause of death and disability wherever people are too poor to afford to vaccinate their dogs, where dogs roam unattended, in animal shelters and in dogs obtained from disreputable pet stores. In prosperous parts of the United States where most dogs are vaccinated, it is now the urban raccoon population, not dogs, that are the primary reservoir of the canine distemper virus. (see here) Foxes, coyotes and wolves are just as susceptible as dogs and raccoons. To see which other animals can catch canine distemper, go here.

How Does This Virus Spread?

The distemper virus is very fragile when it is not inside an animal. It survives less than a day in a typical outside environment. Sunlight, summer-day warmth and dryness rapidly inactivate CDV. It is generally a sneeze or a cough from an infected dog that spreads the virus to another dog. Since the virus is present in an infected dog’s lungs before the dog feels ill, a single sniff, a greeting or a lick on the muzzle is all that is required to pass the virus on to your dog. Once the disease is in full bloom (systemic), the distemper virus is present in all body secretions, urine, feces, tears and saliva. (read here) So even kennel workers can track this disease from dog to dog on their shoes, on food utensils or on their hands.

How Long Will It Take After My Dog Is Exposed For It To Become ill?

It generally takes 4-7 days after exposure for your dog to begin to feel ill. That might begin with a loss of appetite, a slightly depressed mood and a low fever. That often progresses to a soft cough and eye and nasal discharges. Canine distemper is bi-phasic, a two-wave disease. During the first portion, the virus is reproducing throughout your dog’s body. During the second phase, your dog’s immune system can be severely depressed. If that occurs, your pet has little defenses left against secondary bacterial infections. Many dogs show mild or no signs of illness during the first phase, only to become severely ill during the second phase which allows for severe diarrhea, dehydration and pneumonia.

Some dogs also skip the traditional second phase and are only left with varying amounts of viral nerve damage (twitching, seizures, “chewing gum” fits, snapping at imaginary flies). Mental impairment and occasional foot pad involvement (“hard pad disease”) are late symptoms that are occasionally associated with canine distemper. Your dog is really not out of the woods (safe) until a little over a month has passed since symptoms began or exposure occurred. Occasionally, neurological signs appear even later (3-4 months). Because the course of distemper can be so unpredictable and extended, administering distemper vaccines after the virus is already present in your dog’s body is not that uncommon. That can be easily mistaken for vaccine failure. Vaccines were never intended to be given after or just before exposure. Immunity is not an instant event. So, if a rescue puppy was properly vaccinated at the shelter, it is not the staff’s fault if it develops the disease soon after adoption.

How distemper progresses in your pet also depends on what degree of immunity to the disease your dog might already have. In puppies, that immunity is the residual immunity of their mothers (=maternal immunity), passed on to the puppy through the first milk (colostrum). Once all of those maternally-obtained antibodies against distemper have dissipated (faded), your dog is again susceptible to the disease. But even small amounts of residual maternal antibody in your puppy can lessen the disease’s severity. Disease severity can also be influenced by the strain of distemper virus your dog was exposed to. Some “wild” strains are more virulent (worse) than others. Your dog’s nutritional status, its stress level, its intestinal parasite load and other concurrent health issues also influence the severity of a canine distemper infection.

If My Dog Caught Distemper, What Signs Might I See?

The early symptoms of canine distemper are not unique enough for your veterinarian to make a CDV diagnosis with certainty. Kennel cough, adenovirus-1, canine coronavirus, canine influenza and a large number of other virus and bacteria that infect dogs can all cause the same early symptoms. (read here) It is also not that unusual for young or stressed dogs to be facing several of these viruses and bacteria all at the same time. (read here)

Since your dog’s lungs and airways are early areas that the distemper virus colonizes, a nasal discharge and a cough often appear early. The surface cells of your dog’s eyes are affected early as well. So, canthal matter or a greenish ocular discharge are often present. That is not a specific symptom of distemper. Lots of less serious health issues, including allergies, eye conformation, misplaced eyelashes and dehydration also result in eye mattering. Later in distemper, after the virus has crippled the dog’s immune system, bacteria commonly take advantage of the situation. That can result in pneumonia, gasping, severe diarrhea and dehydration. Dogs at that point have no interest in food. Sometimes even the deeper structures of their eyes are affected resulting in blindness.

But with time, many of those symptoms might subside, and dog owners might think that their pets are on the road to recovery. Unfortunately, many of those pets then begin to show signs of permanent nervous system damaged. Tremors, twitching (tics), chorea, seizures, head tilt, chewing gum “fits”, aimless circling, snapping at imaginary flies and loss of mental acuity frequently occur late in distemper infections. They are evidence of nervous system damage that is usually permanent. A subset (smaller group) of dogs does not show any of the early signs of distemper. Dog owners and their veterinarians only realizes the extent of the damage the virus has caused when those neurological symptoms finally start to occur. Hardening and cracking of the skin of the paws (“hard pad disease”/hyperkeratosis) and of the nose are also two late signs of distemper that occasionally occur. In puppies that survive distemper, their permanent teeth sometimes erupt with tooth enamel defects.

Canine distemper tends to be most severe in 3-6 month old puppies. By 3 months of age, the antibody immunity the puppy received from its mother through drinking her first milk (colostrum, passive immunity) has begun to wane (decrease). Yet, the pup’s own immune system is not fully developed yet. Many dogs of this age also reach animal shelters in a very nutritionally-deprived condition with high internal and external parasite loads that have made them anemic. That also weakens their ability to survive a CDV infection. Most receive their first vaccination against distemper at the door. Those vaccinations can be helpful – but, as I mentioned, vaccines take some time before they are protective. No one has determined with certainty how many days it takes before an initial distemper vaccination provides some protection to your dog. (read here & here) By 9 month of age, incoming shelter dogs are often already survivors of mild cases of distemper or had received vaccinations in the past. That provided them with a solid immunity against the virus. That is a major reason why some dogs in a kennel get sick and some dogs don’t.

Old Dog Encephalitis

Occasionally, an older dog will develop neurological signs that are very similar to those of distemper. That is called “old dog encephalitis”. Those dogs were often vaccinated against distemper in their youth and many had received periodic booster vaccinations throughout their lives. To the best of my knowledge, no one has ever been able to isolate living distemper virus from these older dogs. But hints at the virus’ presence have been found. (read here & here) We do not know why this sometimes occurs or what triggers it. Some think that certain wild strains of distemper virus have the ability to persist silently in a dog’s brain. Others believe that the RNA of wild CDV strains might fuse with the vaccine’s strain’s RNA to create mutant virus with enhanced ability to cause brain and nerve damage. That is similar to what is known to be possible in human measles – a close relative of canine distemper. (read here) Still others believe that nerve cells are innocent bystanders – injured when the dog’s immune system cells attack incomplete distemper virus remnants adjacent to them that have persisted in recovered dogs. (read here)

How Does My Veterinarian Diagnose Canine Distemper?

I mentioned earlier that the initial symptoms of canine distemper are not unique (not pathognomonic). But your dog’s history that you supply to your veterinarian, where you live, the lack of a properly administered canine distemper vaccination at 14+ weeks of age, low lymphocyte/thrombocyte counts (=lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia) during the first week of illness, neurological signs, and sign that suggest many body organs are affected are all suggestive of canine distemper.

Tests that positively identify CDV as the cause of your dog’s illness are complicated and are best performed at central veterinary laboratories. Those tests include tests that show a rising antibody titer (ELISA tests) against the distemper virus and/or tests that look for the presence of the virus itself (e.g. RT-PCR, Quant RealPCR™, Antech Lab’s PCR, RT-RPA). These tests all have their drawbacks. Recent distemper vaccinations or samples obtained from your dog too late in the disease can both cloud the accuracy of the test results. If a dog does not survive, properly preserved tissue samples, sent to a veterinary pathologist, can confirm that distemper was the cause of its death.

stopped here

How Can I Reduce The Risks That My Dog Or Puppy Will Catch Distemper?

Current vaccines against canine distemper are highly effective. The biggest error is beginning your puppy’s three-shot series when it is too young, and then failing to give the crucial 14-16 week booster. You cannot count on the 7-12 week vaccinations being effective, no matter how many shots are given because any of their mother’s antibodies that are still in your puppy’s system inactivate those live virus vaccines before they can be effective. The problem is the veterinary industry which does not emphasize that. All industries want to sell more – not less. It is true that a puppy who has none of its mother’s residual immunity can receive beneficial shots at an earlier age. But after multiple vaccination trips to their veterinarian, too many dog owners become so tired of the visits and the expense that they forgo the most important shot of all – the one at 14-16 weeks. Much better than early shots is to isolate your new puppy from sources of distemper and other virus until you can be sure the shots will be effective. Read more about my thought on that here. If you can’t do that, if you do not know the vaccination status of the dog’s mother, if this is a puppy from an animal shelter or a distressed situation, then the the vaccine schedule suggested by the vaccine manufacturer is the one to follow. Just don’t skip that last shot.

How Long After Infection Can A Dog Still Spread The Distemper Virus?

Many dogs overcome a distemper virus infection with few signs to alert their owners or caregivers that they are ill. Those dogs are still quite active, so they could spread the virus for perhaps a few weeks. Some animal shelters say for up to 3 months. But I don’t believe that that has been scientifically confirmed. Measles virus, a cousin of the distemper virus, can infect others for 4 days before symptoms appear and 4 days after. In North America animal shelters it can be very difficult to determine the source of continuing new infections. If a new arrival dog develops distemper 3 months after their last case was diagnosed, that is not sufficient evidence that the virus was lurking for 3 months in their facility. It could have been that a new dog arrive with a mild case or an early case of distemper. Few, if any animal shelters have the financial resources or spare time to methodically track down how the CDV virus moved from dog to dog in their facility.

If My Dog Catches Distemper What Treatments Might Help?

Veterinarians have not reported any medications or treatments that kill distemper virus within your dog’s body. So, we are limited to “supportive care”. That means assuring that your dog is properly hydrated, administering antibiotics to combat secondary bacterial infections, providing warmth as required, lowering fever with antipyretics when necessary, nutritional support, and the like. Nebulization of antibiotics to combat pneumonia is sometimes helpful. When diarrhea accompanies CDV, medications that slow your dog’s intestinal motility and soothe and coat its intestinal lining are indicated. Many of the young dogs that arrive with distemper have concurrent health problems – intestinal parasites such as hookworms, other parasites, skin and ear infections, and vitamin deficiencies. Those issues also need to be attended to by your veterinarian to improve your dog’s chances of recovery. Some young dogs will recover, and some will not, depending on the strength of their immune system, body reserves and, perhaps, the strain of distemper virus that they were exposed to.

I mentioned several times that the canine distemper virus and the human measles virus are closely related. There is some evidence from measles exposure reports, that vaccinating exposed children within 3 days of the time that they were exposed to the measles virus lowered the number that later develop measles. (read here & here) So in a distemper outbreak, at-risk, unvaccinated dogs might (perhaps) benefit from a post-exposure distemper vaccination. We really do not know.

Veterinarians currently have no way to reduce the chances of lasting neurological damage. But anti-seizure medications (anticonvulsants and neuromuscular relaxing agents e.g. diazepam or phenobarbital) will sometimes make those dogs more comfortable. In desperation, vets have even injected Botox®. (read here) Read about all medications that might be helpful when seizures occur here.

How Can I Disinfect My Premises?

Unlike parvovirus, the canine distemper virus does not survive long when it is not in a dog (less than 24 hours on a warm, sunny day). It is rapidly killed by sunlight, drying, heat and all commonly used household disinfectants such as bleach. When using disinfectants, heavy grime needs to be mechanically removed first.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.