Vaccination Associated Fibrosarcoma Cancer In Your Cat And What You Can Do To Prevent It

Ron Hines DVM PhD

A Newer Fibrosarcoma Treatment

A Newer Fibrosarcoma Treatment

We all know that older cats, like older people, are more susceptible to many types of cancer. But beginning in the late 1980s, veterinarians began to see a strange tumor occurring under the skin of cats at much too young an age. Pathologists, examining those tumors, found that most were composed of malignant, mutated fibroblast cells. Fibroblasts are the cells that hold almost all organ structures of the body together and give them their distinctive shapes. In that role, they form the body’s connective tissue. These particular subcutaneous fibroblasts were the ones that help bond the cat’s skin to the muscle and bone structures below. The tumors were named feline vaccination-related fibrosarcomas or VAS for short. Before fibrosarcoma tumors increased in number, veterinarians had access to cat vaccines that were injected deep into your cat’s muscles (intramuscular). Similar to the tetanus shots you receive. But the newer cat and dog vaccines of the time were designed to be given either subcutaneously or intramuscularly. Veterinarians liked the subcutaneous method of administration. It seemed to cause less discomfort to your cat and, because of the immune system cells that naturally dwell just below the skin, some thought that giving them there produced higher levels of immunity. Given subcutaneously on the nape of the neck or dorsal torso, these shots were also much less likely to hit a major nerve or blood vessel.

Male and female cats of all breeds appear equally susceptible to VAS. However, the rate of growth of these tumors is highly variable. Some begin to develop as early as a few weeks after a vaccination, others not for many years. They spread to distant areas slowly, so your veterinarian can usually remove them. But fibrosarcomas have a nasty tendency of leaving a few cancerous cells behind, giving the tumor a high probability of reoccurring. Usually, the tumor returns in the same general area where it had once been removed. In much fewer cases, they move to other locations in the cat’s body (secondary tumor sites).

The original fibrosarcoma cancer outbreaks were along the North Atlantic coast of the United States – particularly in Pennsylvania. An exceedingly astute veterinary pathologist at PennVet, Dr. Mattie Hendrick, whose photo I placed just above, associated the increasing number of these tumors that came her way with a similar pathology she had seen in earlier post-vaccination site inflammations in cats. She also recalled that this outbreak of fibrosarcoma tumors coincided with the enactment in Pennsylvania of a mandatory every-year rabies vaccination for cats.

The chance of your cat developing one of these tumors is still quite small. We think that perhaps 10–20 cats per 10,000 might developed them. Several years before the tumor’s appearance on the East Coast, there had been an outbreak of rabies in raccoons in the area, which is what motivated the change in Pennsylvania law. This was also a time shortly after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration began requiring certain aluminum-containing additives called adjuvants to be added to the vaccines to increase their potency. Many veterinarians were suspicious that the adjuvants might be a part of the problem.

However, something else is a work that we veterinarians still do not understand. That is because we still see vaccination-assoicated fibrosarcoma tumors occurring more frequently in cluster areas. Veterinarians in North America, Europe and Asia all use the same vaccines and supplies. So how can this be? Perhaps veterinarians in different areas give vaccinations differently because they were taught to do so differently in their regional veterinary schools. Some over vaccinate, some don’t. Some massage the injection site after the shot, some don’t. Some apply moist pre- or post-vaccination antiseptic pledgets, some don’t. Perhaps vaccine temperature at injection is a factor. Perhaps differing genetic pockets or some other factors that differ from area to area are somehow responsible. And because we veterinarians understand so little about the drivers of feline fibrosarcomas, our recommendations on how you might prevent them are no more than guesswork.

Over Ninety Percent Of Cats Do Not Develop Post-vaccination Tumors. But for those that do, perhaps yours, that is little consolation:

Cats are unique among pets in their high susceptibility to inflammation in general and tumors at injection sites in particular. That must have something to do with the way cats respond to skin and subcutaneous trauma and irritants. Veterinary pathologists have noticed that some cats develop inflammations identical to those that precede fibrosarcoma tumors when antibiotics or even sterile water is injected under their skin. Their violent immunological response to contaminated puncture wounds is quite dramatic too. One theory about cat fibrosarcomas is that occasionally a hair is carried in with the injection needle, causing inflammation that eventually leads to a granuloma or tumor. Another theory is that cats that develop sarcoma tumors have inherited a gene(s) that make them more susceptible to this form of cancer. As that theory goes, this gene remains in the “off” position throughout most of the cat’s life and usually causes no problems. However, the gene(s) can be turned to its “on” position by inflammation or infections under the skin. So anything that causes inflammation at an injection site could turn on that gene, causing a sarcoma to form. Again, that’s just a theory. In humans and laboratory animals, chronic inflammation is known to be a precursor to cancer formation. Some describe the micro environment around chemical irritants, such as vaccine ingredients, as being enriched with cytokines and growth factors that can promote cancer. (read here) Cats just seem to be more genetically susceptible to that problem than our other pets.

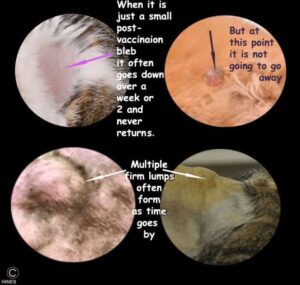

What Do Fibrosarcomas Look Like?

Remember that the vast majority of lumps, bumps and swellings that occur shortly after cats receive vaccinations resolve with time, and do not lead to fibrosarcomas. But if such a situation is accompanied by changes in your cat’s behavior or persistent pain at the injection site, get on the phone with the veterinary staff that administered the vaccine as soon as possible and ask for their advice. When not accompanied by behavioral changes or signs of illness, these lumps, bumps and swellings should be completely gone in a week or two, at the most. When a cat is developing a vaccination-related fibrosarcoma, you might notice a small firm lump when petting or grooming your pet. These lumps are usually about a centimeter or two in diameter and a bit flattened and oblong by the time you notice them.

What to Do If You Find A Suspicious Lump on Your Cat:

Normally, your veterinarian would easily remove skin tumors of this size surgically. We do that with our canine patients all the time. The problem with this particular type of tumor in cats is that its cancerous cells often extend invisibly outward in octopus-like fingers into what appears to be healthy skin and tissue. Most veterinarians are more than happy to have another look at your cat without charge. It should be the veterinarian who re-examines your cat – not one of their technicians. If your vet does not feel that is his or her responsibility, find another veterinarian whose philosophy matches mine.

Often, their advice will be to wait a little longer for the swelling to go away. We wait because a small percentage of cats develop transient post-vaccination inflammation that takes more time to resolve. Those reactions are usually sterile abscesses caused by the irritation and inflammation of various vaccine components. Those reactions often occur 7 – 12 days after the vaccine was given, and also feel like small, firm lumps under your cat’s skin. They appear to go away without any lasting effects. You can request that your veterinarian call the company that manufactured the vaccine for advice on what would be the safest thing to do. You can ask if the vaccine manufacturer agrees to cover the cost of further tests. Don’t bother calling some governmental regulatory agency, such as the USDA. I have never known that to be productive.

Things You And Your Veterinarian Can Do To Prevent Fibrosarcomas:

Give no more vaccinations than your cat’s health actually requires. Avoid mass vaccination clinics, vaccination buses, and yearly cat “wellness” exams where pressure is exerted upon you to agree to vaccination “boosters” your adult cat really doesn’t need. Veterinarians tend to vaccinate adult cats far too often. Adult cats that received their vaccinations as kittens, with a booster at one year, do not require yearly vaccinations. When you do take your cat in for a rabies vaccination, request a recombinant rather than an inactivated rabies vaccine and one that has also been tested and approved for a minimum of three-year duration of immunity. These more advanced formulations might to be less likely to cause injection-site sarcomas. We really do not know. You can read how I feel about the dangers of over-vaccination here. If you decide to forgo vaccine bottle recommendations/directions, you are fighting three very powerful industries, the vaccine manufacturers, the entrenched veterinary industry and local and state governments that refuse to recognize the effectiveness of 3-year minimum duration rabies vaccines.

Give no more vaccinations than your cat’s health actually requires. Avoid mass vaccination clinics, vaccination buses, and yearly cat “wellness” exams where pressure is exerted upon you to agree to vaccination “boosters” your adult cat really doesn’t need. Veterinarians tend to vaccinate adult cats far too often. Adult cats that received their vaccinations as kittens, with a booster at one year, do not require yearly vaccinations. When you do take your cat in for a rabies vaccination, request a recombinant rather than an inactivated rabies vaccine and one that has also been tested and approved for a minimum of three-year duration of immunity. These more advanced formulations might to be less likely to cause injection-site sarcomas. We really do not know. You can read how I feel about the dangers of over-vaccination here. If you decide to forgo vaccine bottle recommendations/directions, you are fighting three very powerful industries, the vaccine manufacturers, the entrenched veterinary industry and local and state governments that refuse to recognize the effectiveness of 3-year minimum duration rabies vaccines.

If you let your cat wander out of doors, you can have your veterinarian periodically determine its degree of rabies immunity through a rabies antibody titer test such as the one above. But even low-titer cats can be resistant to infections because this test does not measure your cats immunological memory, a very important facet of long-term immunity.

Request that your veterinarian use 25 gauge needles when administering vaccines to your cat. Perhaps smaller width hypodermic needles are less likely to cause trauma or carry irritating hair and debris under the skin. (read here)

Request that your veterinarian use 25 gauge needles when administering vaccines to your cat. Perhaps smaller width hypodermic needles are less likely to cause trauma or carry irritating hair and debris under the skin. (read here)

Request that your veterinarian massage the area where the vaccine was administered. A thorough massage outward from the injection site might spreads out irritating antigens and vehicles present in the vaccine, lessening inflammation. I have always done this. To my knowledge, no cat of any client of mine ever developed a fibrosarcoma. Recent studies do not confirm that massage decreases the development of fibrosarcomas. Perhaps I do it more thoroughly, perhaps massage played no part in my feline client’s lack of experiencing these tumors. But I will continue to do so all the same. (read here)

Request that your veterinarian massage the area where the vaccine was administered. A thorough massage outward from the injection site might spreads out irritating antigens and vehicles present in the vaccine, lessening inflammation. I have always done this. To my knowledge, no cat of any client of mine ever developed a fibrosarcoma. Recent studies do not confirm that massage decreases the development of fibrosarcomas. Perhaps I do it more thoroughly, perhaps massage played no part in my feline client’s lack of experiencing these tumors. But I will continue to do so all the same. (read here)

Some veterinarians have begun giving their vaccinations in your cat’s lower legs. Although that technique might appear to be somewhat more painful, they realize that a fibrosarcoma occurring on the lower leg would allow that leg to be surgically removed, but the cat to be saved. (read here) Others suggest that the vaccines be given in the tail, for the same reason.

Some veterinarians have begun giving their vaccinations in your cat’s lower legs. Although that technique might appear to be somewhat more painful, they realize that a fibrosarcoma occurring on the lower leg would allow that leg to be surgically removed, but the cat to be saved. (read here) Others suggest that the vaccines be given in the tail, for the same reason.

Be sure your veterinarian keeps accurate records of the brands of vaccine used and the sites where they were given. Although this may not help your pet, it will help veterinarians determine which brands of vaccine might be more likely to cause problems. To identify the vaccine used, it is now often recommended that the feline panleukopenia-calicivirus-chlamydia-rhinotracheitis vaccination be given on the right leg distal to your cat’s elbow. Rabies vaccination on the lower right rear leg below the knee, as far down the leg as possible. Feline leukemia vaccination is recommended to be given on the same spot on the cat’s left rear leg. That all needs to be noted in your cat’s records as well.

Be sure your veterinarian keeps accurate records of the brands of vaccine used and the sites where they were given. Although this may not help your pet, it will help veterinarians determine which brands of vaccine might be more likely to cause problems. To identify the vaccine used, it is now often recommended that the feline panleukopenia-calicivirus-chlamydia-rhinotracheitis vaccination be given on the right leg distal to your cat’s elbow. Rabies vaccination on the lower right rear leg below the knee, as far down the leg as possible. Feline leukemia vaccination is recommended to be given on the same spot on the cat’s left rear leg. That all needs to be noted in your cat’s records as well.

Many medications (such as corticosteroids, antibiotics, etc.) can be given in pill form rather than by injection. The medication in most tablets will be in your cat’s blood stream in less than an hour. So unless there is a critical need for immediate drug action, avoid as many injections for your cat as you can. In cats, again for unknown reasons, fibrosarcomas are also a rare phenomenon at the site of a variety of injected medications and objects. (read here)

Many medications (such as corticosteroids, antibiotics, etc.) can be given in pill form rather than by injection. The medication in most tablets will be in your cat’s blood stream in less than an hour. So unless there is a critical need for immediate drug action, avoid as many injections for your cat as you can. In cats, again for unknown reasons, fibrosarcomas are also a rare phenomenon at the site of a variety of injected medications and objects. (read here)

What Can Be Done If My Cat Develops A Fibrosarcoma?

Unfortunately, even with aggressive surgery, only a moderate percentage of cats with VAS are cured. As I mentioned before, this tumor is often like an octopus, with unseen tentacles that reach out far from the visible tumor. This means that the first attempt to remove the tumor has to be a radical, major surgery. Your cat’s chances of a cure are likely to be somewhat greater if the operation is performed by a veterinary surgeon who specializes in the removal of feline fibrosarcomas and other highly invasive tumors. Combining this aggressive surgery with radiation therapy might increases your cat’s chance for survival. That is still uncertain. Reviews on the use of Oncept® are mixed. So far, chemotherapy has not been as effective as radiation. You can read more about your cat’s treatment options when it has developed a fibrosarcoma here ![]()

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.