More Wildlife and Exotic Animal Health Care

More Wildlife and Exotic Animal Health Care

More Bird Health Care Articles

More Bird Health Care Articles

Raising Wild Owl Babies

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Should I attempt To Return This Baby Owl To Its Nest?

In my experience, replacing a baby owl into its nest is rarely successful. There are three reasons why. The first is the staggered hatching times of owl eggs (asynchrony). In most other birds, the female, or both parents, do not begin to sit on their eggs until after the last egg is laid. That allows all of their chicks to hatch within a few hours of each other. But a smaller group of birds, including owls, eagles, egrets, herons, pelicans, etc. that is not the case. They often begin incubating their eggs after only a few eggs have been laid, yet they continue laying more eggs. That means that the first chicks to hatch have an important size advantage over the last to hatch. That allows the earlier chicks to monopolize the food that their parents bring to the nest. So with time, the smaller owls are either pushed from their nest or cannibalized. Notorious about this are barn owls. In barn owls there can be as much as a 14-day difference in the owlet’s ages. Nature does things that seem cruel to us for a reason. Most ornithologists suggest that it is only during years when their rodent or other prey is extremely numerous that there is any chance for all of the owl’s chicks to be fed successfully. If so, that might be Natures way of dealing with rodent and insect plagues.

These second most common reason owlets are on the ground is also related to a decrease in available food. Baby owls are more likely to leave their nest, or an adjacent branch, too early or for their parents to abandon them when food is scarce. Hunger encourages owlets to leave their nest too soon. They are often underweight, poor flyers, and unlikely to be successful hunters. If they are only ~30% underweight when you find them, a well-balanced, generously-provided diet should be all that they need for their full recovery. But the thinner they are when you begin, and the shorter their remaining growth period is, the less likely that release into the wild will be successful.

The third is inappropriate nest location. Owls do not always pick the best places to lay their eggs. They have exquisite hearing and vision. Human-generated noise pollution or human, dog, cat, crow, etc. presence can be quite disturbing to them. The tendency of owls to re-use large unstable nesting sites and platforms that they inherit from crows, hawks, squirrels, etc. can also result in owlets on the ground. So can high winds and inclement weather.

Imprinting

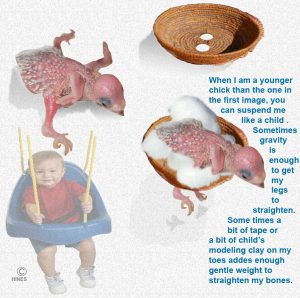

So if you’ve read this far, you know that an orphaned owl’s chances for survival are best if a dedicated, knowledgeable person assists it until it can survive on its own in the wild. If the owl hisses at you, does its “snap-snap” routine or puffs up and weaves it head to look more ferocious like the one in the first photo above, It already knows that it is an owl – and you are not. It is already indelibly imprinted. If so, the dangers of it mistakenly imprinting on people rather than owls is not a major factor. In barn owls for instance, owlets raised by humans from before they were 17-19 days old, such as those in the second photo, become abnormally attached to humans if visually exposed to them such as those in the third photo. If older than 17-19 days, they maintained the shyness required to survive in the wild. (read here) Imprinting is a survival skill that is universal throughout the animal kingdom.

My advice is to remove from your mind any ideas about keeping this owlet as a pet. If that is your intent, please move on to someone else’s website. The owl might learn to tolerate you – what choice does it have? Or you could brainwash it with a technique called “flooding” (aka learned helplessness and resignation) as falconers and animal amusement parks often do. But the kinder thing for you to do for this wild creature whose life you now control is to contact a local wildlife rehabilitation center experienced in raising wildlife with as little human contact as possible – and with the goal of releasing it back into the wild. There will never be enough people in this world with that willingness, ability and resources. Perhaps you could be one of them. If so, read on as some of my advice might be helpful to you. If you have a specific question, you can always ask me.

Imprinting is not only visual. Owls probably learn to identify with the sounds contented owls make long before their eyes open. (read here) In large rehab centers, the nearby presence of mature owls and the lack of a lot of human chatter might be helpful. Once the owlet(s)’ eyes begin to open, most agree that the visual presence of non-releasable adult owls of the same species helps minimize misimprinting.

Always feed owlets from behind a curtain. At the most, they should only glimpse a portion of your hand. Feeding owls at night, rather than during daytime is preferred. But when that is impossible, keep their quarters as dark and as isolated from human traffic as you can.

Long medical forceps such as the ones pictured above minimize close human contact. I often use the reusable one closest to the flight. It is 24 in/61 cm long. Today, hospitals use disposable procedure forceps like the white handled ones you also see in the photo. Hospitals will often give you some if you ask. Once their sterile packaging has been opened or their expiration date has passed, hospitals must discard them, even if they were never used. Commercial grabbers like the blue handled one from Walmart work well for bigger birds such as great horned owls. Infant owls require their prey diced. When they have grown larger, I move prey animals such as dead sparrows or mice around with the forceps similar to a puppeteer until the owls grab it. As time goes by I feed prey to them alive.

No one knows how successful these attempt actually are. We really don’t know how much of an orphaned owl’s behavior is learned and how much of it is dictated by the genes it was born with, that is, how much is instinctive or “hard-wired”. It is always a combination of the two. Genes provide the successful behavior of all prior owl generations; while learning flexibility allows owls to adjust to changes that occur during their lifetime. During a lifetime of caring for owls, I venture that it is about two thirds of the first and one third of the other. But imprinting and misimprinting is definitely quite important. Yesterday a rehabber in Florida mentioned to me that a healthy barred owl was twice brought to her after it attacked people in their front yards. Much like the whitetail buck fawns that later attack golfers in Florida, I suspect that that owl was human-raised and misimprinted.

When baby screech owls and pauraques near their time for release, I often place them in cages with light sources to attract June bugs and other flying insects. Streetlights are another good source of June bugs. Most of the pauraque chicks I receive are mistakenly presented to me as baby owls.

Here Are Some Other Points That Come To Mind:

Owls that are weak, Owls that do not carry their wings symmetrically, Owls that do not use both legs equally well, Owls that will not eat, Owls that have visible blood on their feathers, or stress bars on their feathers or Owls that show any other potential health issue(s) need to be examined by a person with in-depth knowledge about the care and behavior of owls. That only comes with years of experience. Your local veterinarian who cares for dogs and cats is unlikely to know much about the care or diseases of owls.

Owls like consistency. One person needs to be responsible for their care – not the volunteer of the day.

Never keep owls on slick surfaces such as ceramic, metal or plastic. Doing so encourages leg deformities such as Spraddle leg. Owl nestlings need to be housed on a substantially thick, loose matting of small sticks that allows their droppings to drop through and not soil their vent or environment. Hay, straw, mulch or dry grass are not good substitutes. They encourage the growth of toxic molds which can infect their air sacs. Rags often have threads that wrap around and constrict a leg, wing or the neck. These threads and tangles can also be ingested with food and result in impactions. Avoid using them for avian bedding.

Owls have sharp claws (talons). Never clip them. There is never a good reason for you to have an owl perched on your arm. I own no gauntlets or jesses). My leather welder’s gloves are reserved for capture, but in most instances I just gather up birds of prey in a large beach towel, only exposing the area(s) of concern when it comes time to examine them. In birds in poor condition, examination includes their choana for signs of trichomoniasis and tests to confirm normal vision.

Never keep owlets of dissimilar size together. Never keep a strong and a weak owl in the same habitat. As I already mentioned, nearness to other owls of their species helps a young owl confirm its identity. So nearby owls of the same species in separate cages are always a plus. Some rehabbers provide mirrors so that owlets see images of themselves. The photo above is one I provide to many of the songbirds I raise. Something similar might suffice for your owls. Others use camouflaged sheets to cover themselves and hand puppets disguising tweezers at feeding time. Sheets and objects that block the owl’s view of you during feeding and cleaning are a plus. Inanimate owl photos, owl plushes, owl costumes, etc. are cute – but probably not particularly helpful in preventing misimprinting.

Mature owls of the same species do not necessarily get along. Particularly, when introduced to one another as adults. Particularly, when confined to smaller enclosures that do not allow the less dominant owl to escape to a neutral secluded corner. All wildlife in unnatural small enclosures are denied the ability to retreat. That probably accounts for 90% of the intra-species injuries that occur in zoos.

Nature intentionally keeps a young owl’s legs weak. That discourages them from leaving their nest too soon, even when hungry. When a young owl gains the ability to perch, provide it with natural branch perches of diameters that taper and vary – but never so small in diameter that its toenails surround more than half the perch’s diameter. Inactivity, the lack of sufficient flying/hunting time, obesity, smooth perches, damp perches and perches all of the same diameter all encourage bumblefoot. Bumblefoot and the leg arthritis it eventually causes, along with air sac and lung aspergillosis from damp, musty and cramped environments are the plagues of falconers and those who attempt to keep captive owls on display for public or personal enjoyment.

Ceiling fans, glass windows, toilets with their lids upright, hot stoves, cages with tapering bars, vents or chimneys without grates, etc. have all been the demise of escapees.

At What Temperature Should Baby Owls Be Kept?

That depends on their age. I keep owls that are still wearing their down and not yet able to thermoregulate adequately at about 95 – 97 F (35 – 36 C) for their first week of life. Then I drop their environmental temperature about 2 degrees C/3.6 F per week until the baby has a full set of feathers (fully fledged). It is true that the internal (core) body temperature of a mature owl is ~ 104 F (40 C). But keeping birds in an environment of their core body temperature soon causes them to overheat. A sign of an overheated owl is a fluttering chin (gular fluttering) and rapid respiration. I use flexible shaft desk lamps with 40-watt incandescent bulbs placed near the owl’s container as a source of heat. Because of their weak legs, young owls and sick owls cannot be trusted to move to their temperature comfort/”sweet” zone. So, each “nest” container needs to have its own aquarium thermometer that you check regularly. The opposite is also true. Baby owls maintained at too low a temperature do not accept or digest their food well.

I live in the tropics, so I keep the AC/HVAC vents plugged in the rooms where young owls stay to prevent chilling and drafts until they are old enough to move into their outdoor facilities. Outdoor flights need to have multiple hiding places. Owls are very uncomfortable when forced to be in plain view. Besides, resident blackbirds and mockingbirds that spot them torment owls mercilessly. Also, because of that, never release owls in the daytime. Wait until daytime birds have gone to roost.

An Owl’s Digestive Anatomy

If you are interested in raising owls you should know something about the anatomy of their digestive tracts. It is quite different and simpler than the digestive tracts of non-carnivorous, seed and fruit eating birds. An owl’s digestive tract is quite short – even shorter than falcons and hawks. So, it doesn’t absorb nutrients as thoroughly as some birds do. It makes up for that by eating primarily nutrient-rich meat or insects. Owls let their prey do the hard work.

Owls, unlike hawks, eagles and vultures, have no crop. Instead of a functional crop (also called their ingluvies), their esophagus, as well as their glandular stomach (proventriculus), are very distendable (stretchable) and capable of holding an entire rodent or, in the case of great horned and snowy owls, prey considerably larger. Once food reaches its glandular stomach the high acidity there (=low pH of 1.9 to 5 in barn owls) quickly dissolves meat into its protein, fat, mineral and vitamin components. Enzymes produced by the owl’s stomach, pancreas and liver, finish the process of digestion. (read here)

Owls do not have a muscular, grinding gizzard (ventriculus) as found in birds that consume mostly seeds, grains or fruit. The natural diets of soft prey that owls consume do not require it. Their gizzard is thin walled small and flabby. Instead of assisting in grinding, the lining (cuticle) of the gizzard of owls’ primarily job is to protect it from the destructive acids and enzymes of digestion. Because of their soft diet and expulsion of their prey’s bones and feathers as pellets, owls do not naturally consume grit. When small stones are temporarily encountered in their digestive tracts, they were present in the birds they preyed upon. As far as we know, their gizzards secrete no digestive enzymes – although the enzymes of their glandular stomach continue their activity within their gizzard. Owls (strigiformes) often regurgitate one pellet per mouse-size prey animal eaten. They will rarely attempt to hunt again until that happens.

The terms we use to describe the individual sections of the intestines of mammals do not apply well to owls. The absorption-performing portion of their intestine as it leaves their gizzard is shorter than in most other raptors or grain consuming birds and considerably shorter than in mammals. It ends in a pair of cecums or ceca – blind sacs present at the junction of their distal intestine and their cloaca.

We have one cecum, so do hawks, eagles, herons and bitterns. However, owls, similar to gallinaceous (chicken-like) birds, have two rather large ceca that end in two unnamed sac-like structures. These ceca appear to periodically empty themselves. The dark material occasionally voided from them could be mistaken for diarrhea or intestinal hemorrhage. What the function(s) of their ceca are remains unknown. However, the ceca of birds and many mammals contain a large community of beneficial bacteria. In poultry, some of these bacteria produce B-vitamins, others produce products beneficial throughout their body. (read here) Nature does not design anything without reasons – even if we don’t know what they are yet. (read here & here) & ask me for Roggenbuck2014 supplemental.pdf to compare the cecal flora of zoo owls to that of other birds.

Do Owls Need A Water Dish?

Yes.

You might assume that since the prey rodents and other animals that owls consume are about 76% water and feathered prey about 60% water, owls could get along without drinking water. Perhaps they can. However, once owls begin to perch and move about, I add a shallow unbreakable bowl of water to their environment – although I have never seen one actually drink from it. I just feel better giving them that opportunity since they have it in the wild. A smooth stone that takes up two-thirds of the bowl prevents the owl from flipping it over when it attempts to perch on the side of the bowl. Some say that owls enjoy taking a bath. I have never seen that occur in the many owls I have raised either.

I never attempt to give nestling owls water orally. If I am convinced they need hydration when they arrive, I give it by subcutaneous injection. Read about what and how further along in this article.

What Is A Good Baby Owl Diet?

Although owls in the wild are very flexible and opportunistic hunters, it is always wise to feed them prey similar to what their parents would present to them in the wild. Most wildlife rehabilitators purchase frozen mice, rats and day-old chickens from sources present on the Internet. A variety of insects can be purchased online as well. A very kind game warden drops off live mealworms, black soldier fly larva and dubia roaches for the smaller owls I raise as well. Our compost pile supplies an assortment of grubs. But I also trap a large number of English sparrows. To successfully catch sparrows, the entrances to your sparrow traps need to be almost exactly 15/16th inches wide (23.8 mm). Any smaller and the sparrows can’t enter. Any larger and the sparrows find their way out. The occasional titmouse that manages to get in gets released. Some rehab centers feed their raptors the non-native, the excessively common or hopelessly injured species that arrive at their door. They generally do not advertise that – but it is a common practice. All food items need to be diced into appropriate sizes small enough to be easily swallowed. As the owls grow, feed the whole carcass – minus claws, beaks and rodent teeth if you wish. What the owl doesn’t need it will regurgitate later as a pellet. English sparrows are about 68.4% water, 15.9% fat, 64.9% protein, 0.43% crude fiber, 0.94% calcium on a wet weight basis and 0.74% phosphorus.

If you feed owls non-commercially grown prey animals, some believe it wise to freeze those products at 0° F/-18° C, a typical home freezer temperature, for a week or two to kill any possible parasites they might contain. However, owls naturally feed on sick and injured prey. Like vultures, the high acidity and powerful enzymes of their digestive tracts appear to protect them. Owls are opportunistic predators. Even larger species of owls will eat insects when larger prey is lacking. In 85 localities inspected, the pellets of barn owls averaged 91.1% small mammals and 8.9% birds.

How Much Should I Feed?

Adult owls in the wild are thought to eat about 10-15% of their body weight per day. In the wild, they would not always obtain that amount and, depending on their hunting success, some days would consume considerably more or less. Based on what we know about the rapid growth of owlets, they are likely to require double that amount of a high-protein diet. I feed growing owlets whenever they show an interest in food dangled in front of them. When their minds drift off to other things, it is time to stop. Smaller species of owls require more food on a per-weight basis than larger owls such as great horned owls.

Supplementary Food

In a pinch, owls will thrive on supermarket chicken. None of the raptors appreciate the enormous amount of subcutaneous fat present on obese American market poultry. But when the fat is removed, all raptors will accept commercial poultry. Red meat alone is deficient in the B complex vitamins, the fat soluble vitamins A, D & E as well as in calcium. However, a once-a-week offering of chicken or turkey liver appears to furnish all the vitamin A that they need and a drop of cod liver oil per 80 grams of diet appears to furnish adequate vitamin D3. Adequate calcium can be supplied by crushed chicken backs or by a third of a teaspoon full of powdered eggshell per 80 grams of diet.

Pellets / Castings

The photo above are some barn owl castings from one of my flights. Each one represents one English sparrow. The tree ducks and a couple of mallards are just curious background visitors looking for a handout. Birds that subsist primarily on the meat of their prey need a method to rid themselves (regurgitate) indigestible items. In owls, the time from swallowing to the regurgitation of the unwanted portions as pellets is highly variable (6-25 hours). It takes less time when an owl is still hungry after eating and spy a new prey. Just the sight of a potential prey appears to stimulate them to clear digestive tract room. In captivity, an owl’s urge to kill their prey appears to be separate from their desire to consume it. I have had great horned owls kill the small birds that I feed them, only to see them still holding the prey in their talons an hour or two later. These prey animals spends only a short time in the owl’s fore stomach (its thin-walled glandular stomach or proventriculus) before passing into their gizzard. It is there that the majority of breakdown of food proteins begins, while the remaining bones, skin, feathers, etc. are being slowly compressed into an elongated pellet or cast. The cast ends up to be the same size and shape as the space within its gizzard. That process can take 6-8 hours, at which time those remaining prey residues are regurgitated. Besides owls, hawks, eagles, seagulls, cormorants, crows and ravens have the ability to regurgitate prey residues as well. Not all of the bone consumed is egested (expelled). Some of the softer cancellous (sponge-like) bone calcium and other bone nutrients are absorbed. The barn owls I care for generally egest 1 pellet per meal. But in the wild, it is not uncommon to find five or even six vole skulls in a single barn owl pellet.

According to one observer, great horned owls observed in the wild while eating primarily mice expelled pellets about once every three days. So by counting castings present under their roost trees, he was able to estimate how long the owls had been sleeping there. He wrote that the average time between a meal and a pellet in Eastern screech owls was 11.86 hours. There is great variation in this because regurgitation timing is dependent on the size of the prey consumed, the nature of the prey, the availability of a subsequent meal, the time of day and many other factors. Once fully compressed in the owl’s gizzard, the pellet is forced back into its fore stomach where it spends the majority of its time before being expelled. That is why owls show little interest in eating again until that pellet has left and freed up available space.

How Fast Do Baby Owls Grow?

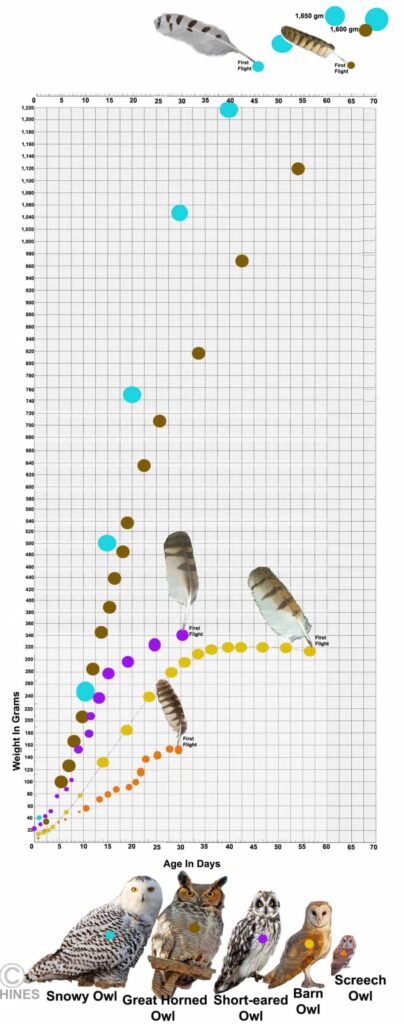

I composed the graph you see above from observations published many years ago in The Condor and The Wilson Bulletin. No one seems to have an interest in recording bird growth rates anymore. I also have growth curves for long-eared owls and western screech owls. I didn’t add them because my graph was getting too cluttered. I will send you some of those dusty old articles in PDF if you ask me for them.

The endpoints with the feathers are the approximate times that the offspring were observed to have left their nest – not the time that they were capable of independent living, which can be considerably longer. Depending on clutch size and the availability of prey, owls at that point are often slightly heavier than their parents. Yet, you will see that leaving their nest is traumatic for them, because there is often a slight dip in their weight at that point. I joke with my wife that the screech owls we raise develop ADHD at that point because they become “antsy” and crash into walls during their first attempts to fly. Windows need to be curtained and other precautions taken. Since they are all fed regularly, it is evidently a hormonal thing and not parental exhaustion nor hunger that drives that behavior. I am told that this behavior occurs even earlier in short-eared owls that nest on the ground – perhaps due to their increased vulnerability versus owls that nest higher up. Some call it branch or nest dispersal. Great horned owls and barn owls are considerably slower to reach that stage (~49-56 days).

Like hawks, falcons and eagles, female owls of all species generally weigh more than the males. Adult body weights also vary depending on where you live. In areas where food is plentiful, owls tend to be a bit larger than those of the same species that live in areas where their food is harder to find. In the arid southwestern United States and dry areas throughout the world, owls tend to be somewhat smaller.

Housing And Flights

When owls are fully feathered, I move them into outdoor flights. The exceptions are owls with medical issues. My flights either have suspended mesh floors or are on sloping cement slabs. All my cages (aka mews) have multiple high hiding nooks. Owls dislike being seen. Roofs are sloping galvanized steel. Mesh walls are 1/4 inch galvanized hardware cloth for smaller owls, 1″x1″ inch mesh for larger birds. To hold up against rusting over time, metal mesh needs to be hot dipped after welding – not before welding as is common when sold in big box stores. Door frames are welded from disassembled bed rails. Hinges and latches are regularly lubricated with lard.

An annoying problem with wildlife rehabilitation in my area are fire ants. They can be lethal to birds – especially to those with mobility issues. I solve that problem on suspended four-poster cages by coating their four 4″x4″post legs with a mixture of all-purpose automotive grease and permethrin. That repels ants well for one summer season. By the following year, enough debris and dead ants have accumulated in the grease to require reapplication. Flights with concrete slabs are a more difficult challenge. I search for the mound(s), apply bifenthrin 0.2% granules and then cover that area with cardboard held down by bricks. Bifenthrin is less toxic to birds than most insecticides. (read here)

Baby And Adult Owls That Arrive With Medical Issues:

Dehydration, Hyperthermia And Hypothermia

And Hypothermia

Dehydration occurs rapidly in young owls when they are exposed to the sun on hot summer days. It occurs to a lesser extent in injured adult owls that have no access to water-containing prey or standing water. Dehydration occurs more rapidly in immature owls because their surface area is greater in relationship to their body mass. As I mentioned earlier, owls dissipate much of their excess heat by rapidly vibrating their upper throat and the membrane that bridges the two sides of their lower beak (gular flutter). Their unfeathered legs are another important site of heat loss or conservation. Perhaps one of the many reasons birds often stand on one leg. The same weight-to-surface area effect makes baby owls much more susceptible to hypothermia as well. Owls have a dilemma to deal with here because the more water they encourage to evaporate to cool their bodies, the more likely they are to become dehydrated.

So, when owls arrive with those issues, besides a warmer or a cooler environment as appropriate, I often I give them injections of 5% dextrose in 0.45% sodium chloride. That is the same sterile fluid that physicians give as an intravenous drip to children that are dehydrated by diarrhea, lack of water, heat exposure or fever. Owls, like most birds, do not have the stretchable skin of mammals that allows for the injection of sizable amounts of subcutaneous fluid. It either has to be given subcutaneously and very slowly at multiple lateral (on their sides) locations or given by other means. I use 29 gauge/0.33 mm insulin or 25 gauge/0.5 mm TB syringes – with a finger placed over the needle and skin at the point of injection so that no backflow occurs and then a gentle finger massage of the area.

If injections are not an option for you, I suggest that you begin owls with these issues on a very wet slurry of blended canned cat food, and whole raw egg – liquefied enough in a blender to pass slowly through a syringe or eyedropper if they will swallow a drop at a time. If not, then through a portion of a 10-14 Fr (aka French) urinary catheter placed down to their thoracic inlet. Although all raptors have fewer taste buds than mammals, I believe that they are less likely to inhale blended umami-tasting food into their lungs than if you attempt to give them pure water or Pedialyte™. No cooperative owl is available to me as I write this article. But the young- of-the-year cooper’s hawk you see in the photo above came in a few days ago. It was severely underweight and dehydrated and would not eat on its own. Not all young-of-the-year raptors succeed in become successful hunters.

If you must tube feed raptors a homogenized diet, you need to be sure it contains sufficient calcium and vitamins. Commercial pet foods cannot be relied upon to provide enough – especially for fast-growing birds. An excellent source of calcium is finely powdered eggshells. A Krups™ coffee grinder, like the one in the photo above, powders eggshells into fine calcium dust. Be sure to do this outside – not indoors as in the photo.

Broken Bones

The next most common health issues I deal with in young owls are leg and/or wing fractures. I believe that the most common causes are being stepped on by a parent owls while presenting them food, inter-owlet aggression and fall from their nest in that order. I also get twisted legs due to a leg being trapped in a crevice or between the sticks of the nest. Fortunately, the bones of rapidly growing young owls are still quite flexible. So, if you treat them with early stabilization, these leg fractures usually repair well enough for a chance at future release. But wing fractures are more problematic. The results can be cosmetically excellent. However, return to close to 100% flight ability is required for survival in the wild. That is quite difficult to achieve. That goes for coracoid avulsions and fractures as well.

In adult owls with fully calcified bones, leg and wing fractures break with knife-sharp edges that quickly damage surrounding ligaments, blood vessels, muscle tissue and nerves as the birds struggle to avoid capture or to fly. In those birds, the injured wing or leg, is often slightly cooler, puffier or darker than the uninjured one – never a good sign. Hollow bones are a portal to the bird’s air sac system, so they are also a portal to infection. Dealing with these fractures is always a challenge. My plan this past summer was to experiment with a dentist friend of mine using various quick-setting dental adhesives. However, my wildlife case load last summer and my refusal to intentionally injure animals precluded that. If you have experience using zinc polycaboxylate, glass ionomers, resin modified ionomers or similar dental bonding agents on avian bone, or can supply me with any of these products, please let me know.

Fortunately, in baby owls and other birds, most leg and wing fractures are what veterinarians call “green stick” fractures – fractures that are incomplete. If held in their proper position, those fractures will heal miraculously fast. You can see what some of those fractures look like and methods I use to deal with them here.

Other than good surgical technique and experience, the greatest challenge is rigid stability of the broken portions of the bones in as close to exact, correct, apposition as possible without impeding the blood circulation required for healing. Birds form most of their new, healing fracture-repair bone (callus) on the outside of their hollow existing leg and wing bones; while mammals, having solid bones, form new bone throughout the fracture lines. The more the remaining gap(s) the larger the new bone callus will have to be and the greater the chances that critical ligaments, nerves and blood vessels will be trapped in unyielding bone. That, plus daily adjustment for just-right tightness and support, plus daily finger flexing of the joints before reapplication of external splints are all very important.

Birds, forced to remain on their keel, soon develop pressure ulcers along their sternum. You need to design their habitat with padding and ingenuity to minimize that.

Sometimes birds come in with leg fractures that have already healed at bizarre angles. I have re-fractured them, put them into proper alignment with splints and stainless-steel pins until they re-healed. But I have never had one regain enough function to be releasable. One can search for kindhearted folks to take them in – something government bureaucrats highly frown upon. When the alignment of the legs of birds are not as Nature intended, a common result is something called “slipped tendon” (perosis). Perosis can also be caused by too rapid a weight gain or a deficiency in various trace nutrients.

If you would like to read more in depth about various repair methods for avian fractures, ask me for MacCoy1992pdf, Harcourt-Brown2002pdf, Tully2002pdf & J-M Hatt2007pdf. Everyone likes to put a positive spin on what they have done. But remember that it is unrealistic to suggest intramedullary bone pins for the fractured bones of small wild birds without accepting the collateral damage they are likely to cause to nearby joints. Sometimes the most sophisticated techniques do not end up giving you the best results. It is unrealistic to expect that ordinary x-rays will detect all of the damage and challenges one will face until surgery actually exposes them. For a closer look at the avian skeleton, go here:

Malnutrition And Starvation

Weather and circumstances are always unpredictable – even for parent owls. Excessive rain, not enough rain, too much wind, nest disturbances, large clutches etc. can all mean less food or less nutritious food for owlets. So many young owls arrive at your door thin and weak. They may have jumped from their nest in desperation, or been pushed out by their stronger siblings. Older owls that come in malnourished often have underlying health issues that are not easily detectable. Perhaps a slight vision, joint or beak problem is present. The best way to detect malnutrition in owls is by the shape and quantity of their breast muscles. In healthy owls, the keel bone will be detectable by your fingers only by its greater hardness in relation to the surrounding muscle. In a thin owl, it keel will protrude well above the surrounding breast muscles on either side. The more it protrudes, the worse the starvation. Muscle mass on both sides needs to be equal.

Another sign that an owl is not eating is the passage of small lime-green colored stools. With no food to dilute it, their stools are basically dark greenish or brown bile surrounded by a white ring of urates – the byproduct of metabolizing its own breast and other muscles for energy to sustain its life. It is not unusual for adult owls brought in for collision issues to also be underweight. Perhaps their lack of normal muscle strength made them more susceptible to accidents. In one study, barn owls that were 28% underweight were still able to fly but more susceptible to accidents.

In malnutrition and starvation, a veterinarian, running laboratory tests, might also inform you that the owl’s blood protein level was low (<2 gm/dl) and that its red blood cell numbers were low as well. I mentioned malnutrition because the B complex vitamins that are critical for nerve function need to be replenished daily. The fat soluble vitamins, A, D, E & K, persist in the body longer. You can supplement B vitamins liberally. Vitamins A & D need to be given in moderation, since too much of either of them negatively affects the liver and kidneys. Major overdoses of vitamin E are also problematic. (read here) Calcium also needs to be in constant supply, particularly for nestling owls. All of those nutrients were present within the owl at hatching, most of the water-soluble vitamins came from the egg white and most of the fat soluble ones came from the yolk. But they persist for no more than a week thereafter. Intentional starvation is a common practice among falconers as are the nutritional deficiencies related to starvation and malnutrition.

Head Trauma Collisions And Ataxia

Where I live the majority of owls that come in with these problems are fully grown. Initially, it can be hard for you to identify the ones that are showing neurological signs (ataxia=wobbly), head tilt, blindness, coma, inability to perch etc. due to a collision from those that have consumed a “bad” rat or mouse (read here & here), or those exposed to West Nile virus, or those exposed to insecticides or to a wide variety of toxic substances that their prey were exposed to.

Few wildlife rehabilitators have the financial resources, spare time or the knowledge and facilities required to attempt to sort out so many possible causes. (read here) I just do my best to offer these birds supportive care. When I suspect that the problem is due to a toxin, semi-liquefied high-water-content diets, administered through tube feeding might help flush water-soluble toxins out their system. Such is the case with the botulism toxin (=limber neck) where water flushes are thought to be helpful. Fat soluble toxins such as bromethalin-contaminated rodents (read here), and many other toxins related to eating cyanobacteria-exposed prey (read here), might benefit from a diet high in unsaturated fatty acids. In some animals and in humans, injections of Intralipid® and similar fatty acid solutions seemed to aid in neutralizing a variety of fat soluble toxins. (read here & here) Chicken fat is about 65.5% unsaturated fatty acids. Perhaps providing it orally might be of some value in those cases. We really do not know.

Generally, if owls get better over a 24-48 hour period, I assume that their problem was a collision. Once recovered, I either release them the following evening so as not to compound their stress or keep them in a flight for a few days for further observation, depending on their willingness to eat and stress level in confinement. Some veterinarians call those collisions “bell ringers”.

I have had a few great horned owls arrive abnormally docile. Their eyes remained dilated even when a pen light is directed at them. With an ophthalmoscope, one can see that their retinas have detached, displacing their pectens. I know of no cure for that. A couple of GHOs have come in with severe corneal inflammation and blindness. I suspect that they were blinded by cotton defoliants. I have had no success helping them either.

If you are serious about attempting to rehab difficult cases, obtaining a human oxygen generator is always a good idea. Mine is the reconditioned 5-liter/min unit you see above.

I know that some associate raptor collisions with air sac rupture. The only air sac ruptures I have encountered are those caused by pellet rifles.

Contrary to what is sometimes said, wild birds do not bleed to death from a broken blood feather (a new feather still immature and blue at its base). But it will bleed again prolifically when that feather is disturbed. So, the skin surrounding the feather should be pinched, the feather plucked out and pressure maintained with your fingers until the bleeding stops. A sprinkle of cornstarch might be helpful in speeding the clotting. Other stiptics can be toxic.

A broken talon is a more serious problem. The best you can do is to cut it off at the break with dog/cat toenail clippers, pinching the toe tightly with the fingers of your other hand while you cauterize the remaining end of the claw. I have a hospital electrocautery, but a heated butter knife or soldering iron will do. I often end up burning my fingers in the process of being sure the bleeding has stopped. I know of folks who force the cut talon end into a bar of soft ivory soap to halt bleeding. I have never attempted that, and I don’t suggest you do either.

Topical ointments are never good ideas when applied to birds – particularly those that are petrolatum-based. They defeat the feather’s insulating qualities and are almost impossible to safely remove.

Wild birds have a remarkable resistance to infection through open wounds and punctures that never ceases to amaze me. But they have little resistance when they have been mauled by cats. Perhaps the mouths of cats are highly contaminated. Even tiny, unnoticeable feline tooth punctures are often fatal. Perhaps the stress of capture and then being played with robs them of their will to live. Critical supportive care, antibiotics, steroids, oxygen, fluids, drugs like meloxicam for pain, 24hr encouragement by me and prayer are almost never successful when a cat has gotten to them first.

At What Age Should I Release My Baby Owls?

As soon as baby owls are willing to eat from a dish, I move them into large outdoor flights with many tree branches of various diameters and hiding nooks. For a while, I feed them from the same colored dishes (generally plastic jar lids) that they are already accustomed to. A water bowl weighted down with a smooth stone is always nearby. All my flights have tin roofs to protect occupants from the rain. Owls will tell you when they are ready to be released. They will begin to search for escape routs. You will begin to see tiny fraying at the very tips of their longest tail feathers. The most telling evidence that you are a few days late in releasing owls would be the beginnings of any scraps at all on their cere. By then, I hope you have already accustomed them to catching live prey. Owls often weigh slightly more fully fledged than their parents. I believe that is Nature’s way of providing them with a bit extra time to perfect their hunting skills. You can get a general idea at what age that happens from my weight graph or the source articles from which I produced it if you ask me for them. For smaller owl species, I do a “soft” release when I can. I attach a little wooden “diving board” ramp to their feeding door left open, but continue to provide them their nightly meals. You see it in the second of the two photos above. When they don’t return for their nightly snack for two or more days, I know they are on their own. For great horned owls, I have a friend willing to release them adjacent to the Yturria Ranch, a wildlife sanctuary of 6,431 acres surrounded be even larger, virtually uninhabited, tracts of land.There, they are unlikely to encounter humans. The first photo above is a little elf owl that came in as just a little fluff. It is the smallest owl in the world, and I am fortunate to live in the only little strip of tropical Texas where they breed.

Never release an owl until sunset when other birds have gone to roost. Mockingbirds, crows, grackles and jays will bother them mercilessly.

Infectious Diseases Of Owls

It is highly uncommon for owls to naturally acquire infectious disease. Many carry low numbers of internal and/or external commensal or self-limiting organisms; but in numbers too low to affect their health under normal conditions. Diseases are much more likely to occur in the birds of falconers, zoos, display and captive birds whose lives are dependent on humans. People are incapable of providing a duplicate of what Nature intended to provide them. That goes for diet, habitat and environmental interactions of all kinds. When those issues cause clinical disease in owls, there is almost always some other underlying problem, usually man made, giving parasites, bacteria or virus the upper hand. There are exceptions, the plagues that periodically occur throughout the animal kingdom when populations become too large. When you or your veterinarian decide that medications are required, choices and dosages for owls are thought to be the same as those for domestic poultry.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.