Ron Hines DVM PhD

Ferret Health Care Library Link

Ferret Health Care Library Link

Many veterinary articles list lymphoma as the third most common cancer in ferrets; the first two being adrenal gland tumors and insulinomas of the pancreas. Others place lymphoma higher on the list. I do not know of anyone who has actually reported more than what arrived at their particular facility; but veterinarians who treat many ferrets like I do tend to agree that it is a very common ferret problem. Lymphoma becomes more of an issue as ferrets age (~4+ yrs). In an aging ferret, it is not uncommon for both adrenal gland tumors and lymphoma tumors to occur together. In ferrets with inflammatory bowel disease, it is not uncommon for the intestinal inflammation of IBD to eventually morph into lymphoma.

Veterinarians often use the words lymphoma and lymphosarcoma synonymously – unlike in tumor medicine where “-oma” generally refers to a tumor that is less aggressive while “-sarcoma” refers to one that is more severe (more likely to metastasize and affect the entire body).

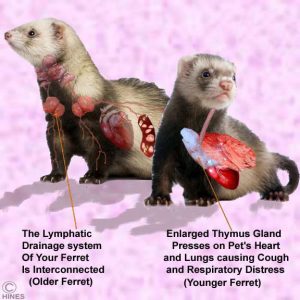

Lymphoma tumors can form in any portion of your ferret’s body. These tumors are composed of lymphocytes. Lymphocytes are an essential part of your pet’s immune system. They protect its body from invading pathogens. (read here) To do so, they must have the ability to multiply rapidly when directed to by the immune system. But when that immune system breaks down, it can allow these cells to multiply out of control. That results in a vast clone of abnormal lymphocytes lacking their normal protective abilities. There are three distinct subtypes of lymphocytes that can mutate in this way. The subtype that appears to give rise to the largest number of ferret lymphomas is the T-cell lymphocyte.

Not all ferrets that develop lymphoma are older adults. A smaller percentage of them are quite young. In those younger ferrets, many veterinarians suspect that the tumors occur as the result of a viral infection. No virus has as yet been discovered, but similar lymphoma-generating virus have been confirmed in a number of other species. Lymphoma is also the most common form of blood cancer in people. There is absolutely no evidence I am aware of that lymphomas in ferrets can spread to humans or other animals.

Some veterinary pathologists attempt to give specific names to individual lymphomas based on the characteristics of the lymphocytes they see in your ferret’s tumor(s). Human physicians do the same thing. But unlike in human medicine, through 2019 there is no data that suggests that one form of treatment is more likely to benefit a ferret with a particular subtype of lymphoma than another. A ferret lymphoma judged to be highly malignant sometimes responds to treatment better than one that a pathologist judged to be less malignant.

What Causes Lymphoma In Ferrets?

In humans and dogs, the specific causes of lymphoma are unknown. In ferrets, it is also guesswork. For one, mature ferrets appear to be highly susceptible to cancers of all sorts. If that is just due to wild polecat genetics, if it is due to inbreeding, if it is due to the diets we feed or some other characteristic unique to domesticated ferrets and their husbandry we do not know. As wild American black-footed ferrets age (>3 yr old) they are also prone to developing tumors. But in the only study I know of, lymphomas were not recorded as being among the tumor types seen. (read here)

As I mentioned earlier, many veterinarians also suspect that a virus might play a part in generating these tumors – particularly in younger ferrets. No such virus has as yet been isolated; but one study appeared to be able to transmit a “prelymphoma situation” from one ferret to another by injecting cancerous lymphoma tissue obtained from another ferret suffering from the disease. (read here) Lymphoma outbreaks have also appeared in rapid succession in multiple ferrets in the same household. (read here)

Other veterinarians suspect that lymphoma with intestinal involvement might be the end stage of long-standing inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Lymphocyte infiltration (invasion) of the walls of the intestine plays a large role in ferret IBD.

When the stomach and/or upper intestine is involved, some veterinarians found an association with a common bacteria of ferrets, Helicobacter mustella. (read here) However, many ferrets that appear perfectly healthy also harbor this bacteria.

My opinion is that lymphoma tumors can begin in multiple ways. It is clear that at relatively young ages (when compared to dogs and cats), the immune system of ferrets is no longer able to keep a variety of cancers in check. Lymphoma ferrets commonly have multiple forms of cancer simultaneously developing in their bodies.

Lymphoma In Juvenile Ferrets

When a ferret under 2 yrs old develops lymphoma, it usually comes on suddenly. The most common area affected is the mediastinum, the central tissues that separate the left from the right side of the chest and which contains the heart, trachea and esophagus as well as lymph nodes and the pet’s thymus gland. The swelling of these lymph nodes and/or the thymus gland with the cancerous lymphocytes of lymphoma causes these ferrets great distress when breathing (=dyspnea).

Adult Onset Lymphoma

The progress of lymphoma in mature ferrets is usually considerably slower than in younger ferrets. They are often brought to their veterinarian with the complaint of a general decline in overall health, weight and energy. I mentioned earlier that lymphomas can appear anywhere in the body. What signs these mature ferrets show depend entirely on where the tumors are located, their size and how long they have been there.

If My Ferret Develops Lymphoma, What Signs Might I See?

If My Ferret Develops Lymphoma, What Signs Might I See?

The early signs of lymphoma – especially in adult ferrets – are vague, variable, subtle and easily overlooked. You or your veterinarian should frequently weigh your ferret. Over time, you might record seasonal changes; but any weight loss that does not fit your ferret’s traditional pattern is a signal that a veterinary exam is in order. A scale is always a wise investment.

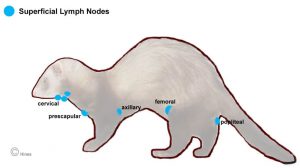

Many ferrets present to their veterinarians with enlarged superficial lymph nodes like the ones in the fanciful diagram at the top of this article. That is not because that occurs in the majority of ferret lymphoma cases. It is because when it occurs it is so striking. The tumors are firm and not painful to the ferret when you squeeze them.

As I mentioned, ferrets with lymphomas in their chest can have great difficulty breathing. That varies from an increased respiratory rate all the way to gasping for breath. Those ferrets are upset and may bite when restrained. They may also faint or pass away from the simple act of restraining them for a closer examination.

As in cardiomyopathy, their rear legs can be weak. Rear leg weakness is a general sign of many ferret illnesses. But on rare occasion, lymphoma does occur in the spine of ferrets. That can account for the paralysis seen.

When lymphoma disease is generalized and many organs are infiltrated with the tumor, just about any symptom of ill health is possible. Those can be related to the liver (such as jaundice, liver enlargement, ascites), the kidneys (uremia), anemia (bone marrow suppression), the intestines (diarrhea/maldigestion) and increased susceptibility to infections also due to bone marrow suppression. (read here) When lymphomas occur near the heart, heartbeat and function suffer as well.

How Will My Veterinarian Diagnose Lymphoma In My Ferret?

How Will My Veterinarian Diagnose Lymphoma In My Ferret?

It is unclear if the majority of lymphoma cases in ferrets have enlarged superficial lymph nodes (=peripheral lymphadenopathy). But if your ferret does have them; and they are firm, non-painful, and similar to the ones in the fanciful image at the top of this page and present at these points on its body your veterinarian will be quite suspicious of lymphoma. Most often, multiple nodes on both sides of the body are enlarged. Your vet will probably want to send a biopsy specimen from one of those nodes on to a pathologist for confirmation.

An analysis of your ferret’s blood might discover that the number of circulating lymphocytes is elevated when lymphoma is present. However, even more ferrets with lymphoma present with normal numbers of lymphocytes in their blood stream.

Your veterinarian might palpate an enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) and/or enlarged liver (hepatomegaly) in your ferret and confirm that through ultrasound and x-rays. Both conditions can occur due to the presence of lymphoma cancer in those organs. But enlargement of those organs occur in several ferret diseases that are not lymphoma and only a biopsy of the organs themselves that detects malignant lymphocytes confirms lymphoma.

When the lymphoma has penetrated the liver, liver enzyme tests are generally elevated. When it has affected the kidneys, test results such as BUN and perhaps creatinine will be elevated as well. Blood calcium levels are occasionally elevated.

X-rays

X-rays

Radiographs are quite helpful in visualizing lymphoma tumors in a ferret’s chest. As I mentioned earlier, these are often located between the lungs in the mediastinum – an area that is normally rich in lymph nodes. In younger ferrets with lymphoma, the thymus gland often enlarges in this area as well, restricting the pet’s ability to breathe. When lymphoma tumors are present in the chest, they tend to obstruct the normal flow of lymph or generate exudates. That leads to pooled fluids (plural effusions) in the chest, which, when present, are often visible on x-rays.

Some veterinarians consider an enlarged spleen (splenomegaly) to be a separate issue. X-rays should confirm its enlargement. An enlarged spleen, containing cancerous lymphocytes can be one element of lymphoma. But it can also be enlarged with lymphocytes that do not appear to be cancerous. Many veterinarians consider those cases to be pre-lymphoma states. Only a biopsy will sort that out. In some cases, the ferret’s liver and/or abdominal lymph nodes will be enlarged as well. That too can lead to abnormal amounts of free abdominal fluid. (read here)

An Ultrasound Examination

An Ultrasound Examination

Of all the tests your veterinarian is likely to perform, an ultrasound examination is probably the most important. What your veterinarian will be searching for are enlarged lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy) as well as changes in the texture and shape of various body organs that might have been invaded by lymphoma cells. An ultrasound unit is also the best apparatus for guiding biopsy needles to the precise locations needed to take tissue or cell aspirate samples to submit to a pathologist. Those are often samples from the pet’s intestinal (mesenteric) lymph nodes, liver and spleen.

Biopsies And Cytology

One cannot diagnose lymphoma with certainly without visualizing individual lymphocytes that have the typical characteristics of cancer, or finding lymphocyte aggregates in locations where they should not exist that are interfering with organ function. Pathologists look for things like too similar (homogeneous) a lymphocyte population, a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio, variably and clumped chromatin, bizarre lymphocyte shapes and irregular nucleus shapes (irregular contours). This is not a precise science. So, disagreements and mistakes in deciding if lymphoma is present are not unusual.

Diagnosis with certainty is not something practicing veterinarians like me are likely to do when it comes to lymphoma in ferrets. As we accumulate experience, we tend to make diagnoses based on probability, the pets that came through our hospitals in the past and the treatments that benefited them the most.

What If My Ferret Only Develops An Enlarged Spleen?

What If My Ferret Only Develops An Enlarged Spleen?

An enlarged spleen is a common finding in older ferrets. When enlarged, your veterinarian can readily palpate (feel) it. It is best to follow that up with an ultrasound examination.

An enlarged spleen is also a common finding in a number of ferret diseases that have nothing to do with lymphoma. But when biopsy samples indicate that splenic lymphocytes are cancerous and there is no evidence that these cells have moved to other locations, you have the option to have the spleen removed. Otherwise, I only contemplate removing the spleen if it has gotten so large that it is prone to rupture or when the spleen’s increased size interferes with digestive or liver function.

I do not believe that a ferret’s spleen should be removed without sufficient cause to do so. The loss of a spleen predisposes to later infections and can cause minor infections to become major ones. (read here & here)

What Treatment Options Are Available For My Ferret?

What Treatment Options Are Available For My Ferret?

If your veterinarian confirms that the lymphoma is restricted to a single accessible site such as the spleen, a kidney or a cutaneous (skin) lump, that lymphoma can be surgically removed. In some cases, ferrets in those situations have gone on to live another year or two after the surgery was performed. Most veterinarians would tell you that the chances for recovery would be greater if the surgery was followed by chemotherapy. That may or may not be true, no one has really determined that.

Prednisone/prednisolone?

Prednisone/prednisolone?

Either of these corticosteroids reduce the number of lymphocytes in your ferret’s bloodstream. They also reduce the normal migration of lymphocytes from the ferret’s bone marrow and thymus gland to its lymph nodes and, in so doing, shrink the nodes. These steroids (and others) mimic the effect of the body’s own corticosteroid, cortisol, produced in its adrenal glands.

However, this effect on the ferret’s lymphocytes and lymph nodes does not last. It usually gives relief only for a while (several months?). Corticosteroids will also produce a number of side effects: increased appetite and fluid retention, slowed healing, and occasionally pancreatitis, diabetes or liver enzyme elevation.

Some veterinarians believe that these medications make a later use of chemotherapy drugs less likely to be effective. I do not know that that is true because prednisone is included in the standard CHOP therapy for human, dog and cat lymphoma. Considering the uncertain benefits of chemotherapy in prolonging the lives of ferrets with lymphoma, I find these corticosteroids a valid option – particularly when your ferret is old in ferret-years.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy

While corticosteroids like prednisone attempt to suppress the number of cancerous lymphocytes hormonally, there are a number of drugs that seek to kill these mutated lymphocytes outright. Unfortunately, they are not selective. Malignant tumor cells divide rapidly. But these drugs target all body cells that are dividing rapidly. So other tissues such as the bone marrow and intestinal lining can feel their toxic effects as well. All were developed to fight cancer in humans. The few studies that attempted to gauge their effectiveness in prolonging the lives of ferrets had too few and too dissimilar animals enrolled to contribute much to our general knowledge.

Cocktails of these drugs have appeared to cure or produce long-term remission in many young ferrets. But older ferrets are lucky to gain a few more months of low-quality life subsequent to treatment. So, I never recommend chemo for them. In the opinion of one eminent ferret specialist quoted in 2017, ferrets with lymphoma that receive chemo do not live any longer than those that do not receive chemo. Another 2007 study found that about 10% of them improved (experienced remission). (read here) A third pair of veterinarians stated that “response to chemotherapy was poor [in the ferrets they treated] and that survival times may be very brief”.

Most chemotherapeutic drugs are too irritating to be given to your ferret by intramuscular injection. Most need to be given slowly by injection into a major vein, multiple times. Ferrets being so small, it is usually best for your veterinary specialist (oncologist) to sew a drug port into the ferret’s jugular vein to avoid venous scaring and tissue necrosis.

Chemotherapeutic drugs that have been used to treat ferret lymphoma include L-asparaginase, chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, doxorubicin, methotrexate, procarbazine and vincristine, generally given at the same dose rates given to cats. A popular cocktail among veterinarians for ferret lymphoma consists of vincristine, L-asparaginase, cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin.

To minimize the suffering of chemo, one chemotherapy plan, developed at Tufts University Veterinary School in 2006, allowed all the medications to either be given orally or under the skin (subcutaneously). You can read the drugs and their dose schedule here. A 2019 update from Tufts reported that the median survival time for seven ferrets receiving this treatment protocol was 86 days (range 19-888 days).

There is really no scientific basis for yearly revaccination of ferrets against canine distemper once they have received their initial 3-shot vaccine series (generally one at the breeder and two at your veterinarian’s office). But if for some reason you choose to do so, remember not to do so during or soon after chemo with any still-living (attenuated) virus product.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation Therapy

Radiation is occasionally used to treat lymphoma in ferrets. As with many lymphoma treatments, its benefits are difficult to judge. Some ferrets seem to improve after radiation treatment or when radiation is combined with medications. But because the progress of lymphoma is so variable, it is difficult to judge the radiation treatment’s true effectiveness.

The Minimal Treatment & Acceptance Option

The Minimal Treatment & Acceptance Option

Lymphoma in itself is not a painful condition. Some ferrets harboring this disease live happily for several years and eventually die from other causes. As in humans, when these cancerous lymphoma cells eventually affect other organs, the result is primarily lack of energy, loss of appetite and loss of weight. So, you might decide that no treatment is the kindest option for your little friend – particularly if your ferret is an oldster in ferret years.

Entyce®?

Entyce®?

I have only prescribed Entyce® and Elura® as appetite stimulants to dogs and cats. If you have used Entyce as an appetite stimulant in your ferret let me know. Having tasted it myself, it and its feline counterpart, Eura® are quite bitter and metalic in taste. Let me know how your ferret accepts that taste.

If My Ferret Develops Lymphoma, What Signs Might I See?

If My Ferret Develops Lymphoma, What Signs Might I See? How Will My Veterinarian Diagnose Lymphoma In My Ferret?

How Will My Veterinarian Diagnose Lymphoma In My Ferret?

X-rays

X-rays

What If My Ferret Only Develops An Enlarged Spleen?

What If My Ferret Only Develops An Enlarged Spleen? What Treatment Options Are Available For My Ferret?

What Treatment Options Are Available For My Ferret?

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy The Minimal Treatment & Acceptance Option

The Minimal Treatment & Acceptance Option Entyce®?

Entyce®?