Intestinal Parasites In Your Cat And What To Do About Them

Ron Hines DVM PhD

How Likely Is It That My Cat Has Worms?

Intestinal parasites, respiratory virus and ear mites are the most common problems veterinarians like myself see in kittens. Although pets of any age can carry intestinal parasites, they are primarily a health issue in young cats or cats living in substandard, crowded conditions or cats with other concurrent health issues. If your cat was examined by a veterinarian and wormed as a kitten, if your cat has been with you for over a year, if no other cats have entered your family during that time, if your cat does not go outside unattended, if your cat is free of fleas, if you do not feed your cat raw meat, then your cat probably does not have an intestinal parasite problem. Many of the monthly flea/tick and heartworm preventatives for cats are formulated to kill intestinal parasites as well. They are very effective in doing so. Cats and their parasites have had millions of years to evolve together. During that time, they have begrudgingly learned to tolerate each other most of the time. There are a large number of these worms and assorted freeloaders. I list them below roughly in the order with which I encounter them in my practice.

How Will I Know If My Cat Has Worms?

When intestinal parasites are present, they often reside silently, and you will not know that they are there by looking at your cat or dealing with its litter box. The more common intestinal parasites have adapted so well to their host (your cat), that they usually live in balance and cause no observable health issues. That can always change when your cat is stressed and its immune system can no longer keep parasite numbers under control. It is only when the parasites become too numerous for one reason or another that your pet’s health might be affected. Because of their stealthy nature, your best approach is to try to keep your pets completely free of them before the balance becomes disturbed.

The most common early signs of intestinal parasites in kittens are poor growth (stunting), a dull hair coat, scrawniness (thin/bony), a lack of playful energy and loose stool or diarrhea. Many of these kittens have thin bodies but potbellied tummies. Depending on the parasite(s) they carry, some are anemic. Kittens with a large parasite burden invariably grew up in poor unsanitary conditions. They are often the offspring of feral or semi-feral cats who are themselves stressed and nutritionally deprived. Pregnancy at too young an age and too often favor vulnerable kittens.

It is exceedingly rare for me to find intestinal parasites in indoor cats living in a one or two-cat home. Cats are by nature very clean animals and parasites rely on poor sanitation to jump from animal to animal. However, when cats are forced into conditions that favor parasites, the most common signs of their presence in older pets are lack luster, brittle hair coats, boniness, listlessness, and diarrhea. Some of these older pets might become picky eaters. In a few the opposite occurs. But many show no change at all in their eating habits. In adult cats with an intestinal parasite problem, multiple unrelated health issues are common. It requires a health immune system and body to keep parasite numbers under control.

My Cat Scoots or Licks Its Rear. Is That A Sign Of Worms?

Worms do not directly cause your cat to scoot or lick its rear end. That story originated with human pinworms which can cause anal itching. However, in a round about way, cat intestinal parasites can result in anal irritation. That occurs when irritated intestines cause your cat to have softer than normal stools or diarrhea. As normally formed stools pass over your cat’s two anal glands, they naturally evacuate them of the secretions they contain. When your pet has persistently soft stools, these glands do not evacuate properly and over-inflate with secretions. Like a balloon about to burst, that can bother your pet and cause it to scoot and lick its anal region. The problem is less common in cats than dogs but much the same in effect. In dogs, it is most commonly due to giving them spicy table scraps. Persistent diarrhea also inflames the anus – compounding the problem.

How Will My Veterinarian Check For Worms In My Cat Or New Kitten?

A few types of parasites are large enough to be seen with the naked eye in your cat’s stool. When you bring a stool specimen to your veterinarian, those larger parasites can often be recognized and identified. This goes for various types of tapeworms and for roundworms. However, the rest of the common parasites of cats are too small to be readily seen. And most of them have developed strategies to maintain their position in the upper portions of your cat’s intestine. In those cases, your veterinarian will be looking for the parasite’s eggs or cysts in the stool specimens that you bring.

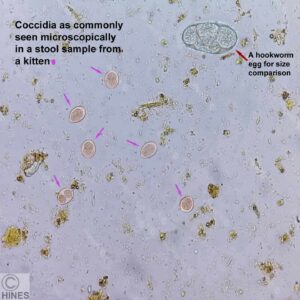

When intestinal parasites are present in your cat in large numbers, your veterinarian may be able to see eggs or cysts in a fresh suspension (“smears”) of the feces placed on a slide with some saline and examined under a microscope. That is the most rapid screening test a veterinarian can perform. However, fresh direct suspensions (smears) miss over half the pets that actually carry parasites. Fresh suspensions are quite good at detecting giardia and other protozoa that live within the intestine in vast numbers, but they often miss hookworms, roundworms, and the very rare cat with whipworms. The later parasites are attached to your pet’s intestinal lining. Your vet is looking for their eggs, not the worms themselves. Those eggs are passed in large numbers only by mature worms with egg numbers reflecting the pet’s parasite burden. Even then, they can be present only intermittently. Direct suspension drops are best used to pass the time with clients while a fecal specimen flotation runs in the veterinarian’s laboratory (about 5–10 minutes). Even if the smear is positive for one parasite, there may be other types found in the flotation suspension. Multiple infections with several species of parasite are quite common.

There are a few intestinal parasites (e.g., strongyloides) that do not float to the top of the liquids used to concentrate parasite eggs and larva by flotation methods. The larva of some of those remain at the bottom of the flotation tube. They can be found there, but most of them are picked up on a direct saline stool suspension and identified by their wriggling motion.

Tapeworm segments and tapeworm eggs are rarely found mixed with feces. They usually pass out of your cat on the surface of its feces. So do not be surprised if your vet does not detect any through flotation methods. You need to specifically bring the suspicious cream-colored segments or strands in and point them out. Any time you bring in a suspected parasite, place it in a baggie with a moist paper towel. When they come to me shriveled and dry like a mummy, it can be quite hard to firmly identify what they are.

Fecal flotation is a way to concentrate parasite eggs and cysts on a slide to make it more likely they will be found. All use a solution that causes eggs to float to the top and most other heavier debris to sink to the bottom of the container. Centrifuging the sample speeds the process. Some commonly used flotation liquids are sodium nitrite (Fecasol®), sugar and zinc sulfate. Saturated table salt will also due, but it is less efficient. When you collect fecal specimens from your cat, always wear gloves. Keep the stool specimen chilled with an ice pack if you cannot get it to your veterinarian quickly – some parasite eggs hatch rapidly at room temperature and the resulting larva can be hard to find.

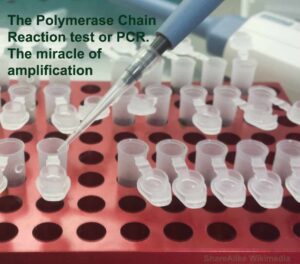

PCR Tests – The Most Accurate Way To Confirm Parasites

Detection of hookworm, roundworm, and whipworm can be difficult with the current diagnostic methods most veterinary hospitals use. First of all, these parasites do not begin laying eggs immediately. So, there is a substantial lag time before your vet is likely to find their eggs in the stool sample from a recently infected cat. The other problem is the number of parasites must be substantial before your veterinarian or his/her technician is likely to encounter an egg in the tiny droplet of material placed on a microscope glass slide. However, a newer, much more accurate test exits. It is called a polymerase chain reaction or PCR test. When used for parasite detection, this test searches for minute portions of the parasite’s unique DNA. If only a few parasites are present, there won’t be much of that DNA; certainly not enough to detect by ordinary methods. However, the PCR test multiplies the amount of the parasite DNA (the amplicon) present in the stool sample you brought in. Each PCR cycle about doubles the amount. Ten cycles multiply the amount by a factor of about one thousand; 20 cycles, by a factor of more than a million in a matter of hours. IDEXX Reference Laboratories offers their Fecal Dx® antigen testing as a tool for detecting these common intestinal parasites. They also offer a separate PCR test to detect giardia and the Company also offers the older, more traditional ELISA test for the presence of hookworms, roundworms, and whipworms. Whipworms are quite uncommon in well-maintained house cats. Antech, which is owned by the Mars Conglomerate, offers their KeyScreen™ GI Parasite PCR test to detect specific parasites in your cat,

Which Are The Most Common Intestinal Parasites That My Veterinarian Might Find?

The veterinary school of the University of Oklahoma did a survey of 2586 cats brought to them for various health issues. All had fecal samples examined microscopically. You can read an abstract of this article here. The actual article is paywall protected by Elsevier. They want money before they will let you read it. But if you ask me for Nagamori2020, I will loan you my copy. If all the parasites were actually living in these cats is uncertain. Some of these parasite eggs could have just been consumed in the food that the cat ate and expelled in its feces without ever infecting the cat. Cats that hunt or receive raw prey will pass the eggs of any parasites that the prey animal contained.

In the majority of cats (75.5%) they detected no intestinal parasite eggs, larva, oocysts or cysts. But 18.8% of the fecal samples were positive for at least one parasite. Almost 6% of the cats were positive for more than one parasite. The most common parasite that they detected was the coccidia protozoan, Cystoisospora (9.4%). The next most common parasite they encountered was the roundworm, Toxocara cati (7.8%). Next most common were the cysts of giardia protozoa (4%). The eggs of a “flatworm” (trematode), Alaria, were found in the stools of 3.5% of the cats. Ancylostoma hookworm eggs were found in the stool of 1.2% of the cats. Taenia tapeworm segments or their eggs were found in 1.2% of the cats while the smaller dipylidium tapeworms accounted for 1.1%. Eggs of the nematode, Eucoleus aerophilus, were found in 0.7% of the cats. In descending order, the eggs of the rat parasite, Physaloptera, eggs of another roundworm, Toxascaris leonina, the flagellate, Tritrichomonas blagburni, larva and eggs of the strongylid, Ollulanus tricuspis, eggs of the liver fluke, Platynosomum fastosum, larva of the cat lungworm, Aelurostrongylus abstrusus, the infectious stage of Sarcocystis, the eggs of the tapeworms, Spirometra and a second unidentified mesocestoid tapeworm, the eggs of the whipworm, Trichuris felis, Cryptosporidium protozoa, and the infectious stage of toxoplasmosis each accounted for less than 1%.

Are These Parasites A Serious Health Hazard To My Cat?

When there are only a few of them, and your cat is otherwise healthy, the common feline intestinal parasites are unlikely to cause health issues. Some, like roundworms and tapeworms, absorb their nutrients through their “skin” (cuticle), so they don’t normally injure your cat’s intestine. But in large numbers, roundworms can cause colic or even intestinal obstruction. However, other parasites such as hookworms have “teeth” (denticles) with which they chew and erode the lining of your cat’s intestine. Strongyloides tunnel through the cat’s intestinal lining, causing inflammation. Single-celled Giardia block nutrient absorption and are thought to produce a mild toxin while coccidia enter and destroy the cells of the finger-like projections (villi) that allow nutrient absorption through your cat’s intestine. Your cat has great potential to brush off the effects of a few parasitic organisms. But when the number of these parasites is high, your pet’s health will suffer. Resultant diarrhea, gives less time for food absorption. Intestinal irritation lessens appetite and can cause vomission (vomiting). Burrowing parasites cause inflammation, blood loss and anemia.

Kittens

Intestinal parasites are always worse when they affect young vulnerable animals. The younger cats are when they are attacked, the worse the problem will be. That is because growing kittens have much higher nutrient needs and their inflamed intestines cannot absorb sufficient nutrients and vitamins. Their ulcerated intestines also leak precious blood. Their tiny bodies lack the mass and reserves to deal with crises and their chief parasitic immune mechanism (mucosal immunity) is not yet fully developed. That immunity must be “trained” by prior exposure to those parasites at low levels. In addition, these small creatures do not move about far from their birth/nest area – so feral litters are continually re-exposed to parasite eggs and reinfection. Some of these parasites, like hookworms, are transferred to the kittens through their queen’s milk (colostral transfer), and, possibly, while still in the womb (transplacental transfer) as well. Others, like roundworms, readily move from infected mothers to their babies while still in the womb. I mentioned that many nematodes, such as hookworms and roundworms do not pass eggs immediately (their prepatent period). So just the fact that your kitten’s fecal exam was negative is no guarantee it is free of worms.

Adult Cats

Adult cats are more resistant to intestinal parasites. Given their natural tendency to cleanliness and private space, cats will clear themselves of intestinal parasites if given half a chance. However, when their environment is highly contaminated or their resistance is weakened, mature cats can become seriously ill due to heavy parasite burdens. Much of the age-related immunity that protects adult cats is acquired by prior exposure. So cats that have not been exposed to a parasite previously may become as ill as kittens if they are suddenly confined to shelter, a group-home situation or a feral colony where large numbers of parasite eggs (ova) are to be found. Adult cats that retain a small number of intestinal parasites are said to be “compensated”. That is, the cat has adjusted to the parasite’s present with a natural immunity similar to vaccination that keeps parasite numbers in check, so it shows no signs of illness. (read here)

Are Parasites Becoming Resistant To The Drugs Veterinarians Use To Destroy Them?

So far, that has only been a problem with hookworms and tapeworms in dogs. (read here & here) But the war against parasites is never-ending and the potential definitely exits for the same resistance problem to eventually occur in our cats as well. Drug resistant hookworms began to be a problem in greyhounds housed close together in less than sanitary conditions. It has now spread to kennels housing other dog breeds. Intestinal parasites have a long history of becoming resistant to the drugs veterinarians commonly used to kill them. Topical moxidectin still seems to be the most effective in destroying drug resistant intestinal parasites. The monthly applied, topical moxidectin/imidocloprid in Advantage Multi®, or its generic clones such as Midamox™ or Barrier™ for cats is approved to cure ear mites, hookworms, roundworms, and heartworms. The imidacloprid is there to destroy fleas. It appears to be a safe product for cats when used as directed. (read here)

When it comes to doses and the safety of medications for your cat, ALWAYS READ THE LABEL ON THE ACTUAL PRODUCT YOU INTEND TO USE. Don’t rely on what you see on chat sites or other information you find online such as mine. We all make typos, we all make mistakes. Product labels change. Label warnings change. Suggested safe doses change. Products intended for dogs can be dangerous for cats.

About Individual Intestinal Parasites:

Hookworms

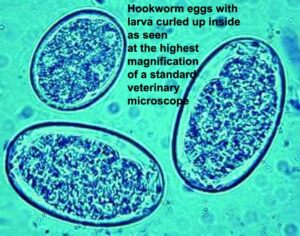

Adult hookworms are very small – barely visible to the naked eye. There are quite a few species of hookworm that attack cats, but the most common and serious one is Ancylostoma tubaeforme, and to a lesser extent A. braziliense. Both attach to the lining of your cat’s small intestine where they feed on blood. The warm, humid climates of the southeastern United States, Southern Europe, Central and South America favor hookworm transmission. Most cats are infected with hookworms by accidentally ingesting (eating) hookworm larva that have already hatched on the ground from the parasite’s eggs. Stool from infected cats can contain millions of these, thin-shelled eggs. When that stool contaminates damp, cool soil and hatches into larva, the larva adhere to your cat’s fur and are licked off during grooming. Hookworm eggs must develop outside of a cat for a time before they become infective (~1-2 days). When the hookworm eggs actually hatch into hookworm larva, they are capable of penetrating a cat’s intact skin and paw pads as well as being swallowed. Rodents that accidentally ingest hookworm larva become infested with dormant cat hookworms in their tissue. It is thought that cats eating these creatures might be a second way these parasite spread. Cockroaches and other vermin that cats play with and eat are perhaps another possible source of infection. Not all locations harbor hookworm larva that are a threat to your cat. They survive best in warm, humid soil. Freezing, drying, and temperatures over 98 F/36.7 C quickly kill hookworm eggs and larva.

After hookworm larva are eaten, a complicated migration process begins that leads to young adult hookworms arriving in your cat’s small intestine approximately 10–14 days later. Once inside the body, hookworm larva gain access to your cat’s circulatory system (blood and lymph). From there, they are carried to its lungs. Once in the lungs, the larva escape and are coughed up and re-swallowed. A cough might even be present at that time. This time around, they attach to the walls of your pet’s small intestine where they feed on blood, mature, and eventually lay more eggs that repeat the cycle. Hookworms do not stay attached to one place. They move around causing intestinal lining (mucosal) destruction and ulceration for all of their 4-24 month life span.

Most infected older cats show only mild, nondescript symptoms of mild anemia, weight loss, poor appetite, and perhaps intermittent vomiting and diarrhea. Some have elevated blood eosinophil count. But Kittens and younger cats with heavy hookworm loads can become quite ill. In kittens, anemia due to hookworm infestation can be fatal. But in most cases, these infestations cause bloody diarrhea, weakness, and vomiting of varying intensity. This can be confused with panleukopenia, another common disease that causes similar signs and the two diseases can even co-exist. Severely affected cats often require hospitalization, supportive care and medications to sooth and protect their traumatized digestive system. Supplemental iron is also helpful, and, of course, a medication to kill the hookworms. Some anemic cats in critical condition have been saved through blood transfusions.

Worming medications that veterinarians have at their disposal are only effective against hookworms that have finished their long migratory journey to your cat’s intestine. Because the time that each individual hookworm arrives in the intestine varies, a single administration of worming medicine is never enough. Because of that, kittens generally receive one of those medications at 6, 8 and 12 weeks of age – perhaps even earlier when a particular litter is at risk.

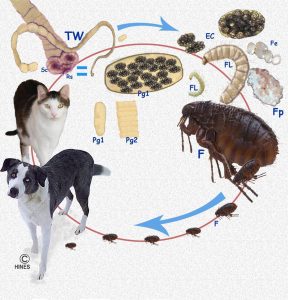

Roundworm Infections aka Ascaridiasis due to Toxocara cati or Toxascaris leonina

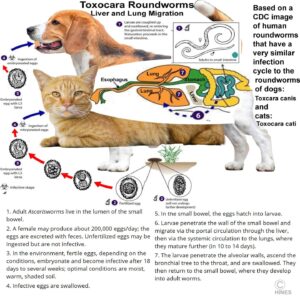

Roundworm eggs that hatch into microscopic larva in your cat’s intestine do not stay there for long. Instead, they migrate through your cat’s body (a liver-lung migration as seen in the diagram I drew above). They are on their way to your cat’s lungs where they are coughed up and re-swallowed. It is on this second pass that they set up permanent housekeeping in your cat’s small intestine.

Roundworms and tapeworms are the largest of the common intestinal parasites of cats. So, they are the ones you are most likely to see in your cat’s stool, particularly after a bout of diarrhea. If your pet is heavily infested with roundworms, these parasites might appear in your pet’s vomit as well. Roundworms are thin spaghetti-colored creatures, 3-12 cm long. When they are not surrounded by feces, they usually curl up in a spiral. Mature roundworms do not attach to the walls of your cat’s intestine. Instead, they have the ability to “swim upstream” in the intestinal contents to avoid being purged in the pet’s stool. Unlike hookworms, cats become infected with roundworms by eating roundworm eggs – not larva. Kittens can become infected within their first three weeks of life when their mother’s milk harbors the immature parasites. Cats that are out and about are more likely to encounter roundworms. Various varmints (rats, mice etc.) that come in contact with roundworm eggs end up with these parasites encysted in their bodies and can transmit them to adult cats if they are themselves consumed. Roundworm eggs are not immediately infective, they need about a week in the environment to activate. Because of their thick outer coating, roundworm eggs are much more resistant to drying than hookworm eggs.

Kittens

Some studies have found that over a third of shelter kittens and young cats are infected with roundworms and are shedding their eggs. That is probably a low estimate of the number of roundworm-positive kittens, since eggs are not always or immediately present. The incidence is lower when cats are not forced into large-group situations. It can be hard to decide when roundworms are the cause of vague poor-health signs in kittens. That is because it is quite rare for roundworm-positive kittens not to have other concurrent health issues such as fleas, ear mites, herpes virus infections, coccidiosis, and malnutrition. When a kitten carries large numbers of roundworms, its hair coat is often shabby, it is likely to be less active and not to grow as rapidly as it should. Roundworms are large motile parasites that thrash and move around in the kitten’s intestine. When present in large numbers, they cause intermittent colic, diarrhea, constipation, and vomission. On rare occasion, worms are so numerous that they block the intestine. Small kittens with large numbers of roundworms have a typical pot-belly. Roundworms have no mouth, so they do not chew and damage the kitten’s intestinal lining or cause anemia like hookworms do. But it is quite common for kittens that have roundworms to have hookworms as well. Luckily, advanced medicines that destroy one, destroy the other.

Adult Cats

Adult cats do not become as resistant to roundworms as dogs. Cats are more likely to continue to shed the roundworm eggs in their stool and for the parasites to continue to live in their intestines rather than retreat to dormant cysts in other body tissues. On rare occasion, a mature roundworm will obstruct the flow of bile through the bile duct leaving the liver. Most adult cats that harbor roundworms show no visible health issues attributable to the parasites. Because roundworm eggs are extremely resistant to drying, your cat will always be exposed to them if it is out-and-about unsupervised. The outer shells of the parasite eggs are quite sticky, so they cling to your cat’s hair coat and foot pads and are accidentally eaten during grooming. You can assume that all outdoor cats are exposed to these resistant eggs. Because many roundworms can be dormant or shed eggs only intermittently, a negative fecal exam is not proof that the parasites are not there. A negative PCR test would be considerably more accurate. That is why some breeders periodically worm their pregnant and nursing cats.

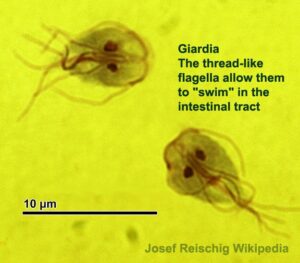

Giardia = Giardia duodenalis G. intestinalis, G. lamblia

Giardia living in your cat’s intestine are single-celled creatures (a protozoa) that move about by means of long motile filaments (four pair of flagella). The adult feeding form is called a trophozoite. It is a rather flattened organism with a broad “suction” disc on its bottom surface that holds it firmly to the intestinal wall (the upper or proximal small intestine). After a period of time some of these parasites round up and form capsules (cysts) that are more resistant. These cysts pass out in your pet’s feces to potentially infect other animals. The cysts can survive for long periods (~8 wks) in cool contaminated water. Freezing, drying or strong sunlight kill them almost immediately, as do most disinfectants.

I see less giardia problems in cats than I do in dogs – probably due to a cat’s more hygienic nature. When giardia does infect a cat, it is usually subclinical (no visible illness). It is also more common in high-density populations such as catteries, shelters, and other high-stress situations. Because giardia produces a sold age-associated immunity, one rarely sees giardia causing a problem in mature cats unless they have another, underlying, intestinal disease. (read here) Just seeing motile giardia in a stool specimen from a cat with diarrhea does not confirm that giardia is the cause of the diarrhea. Any form of intestinal inflammation allows this parasite to proliferate. Age-related immunity can be overwhelmed when your cat is exposed to very high numbers of giardia. That is why a new kitten in a multi-pet household sometimes causes transient diarrhea in the other pets in the household. In addition to cats, most furry household pets, as well as us humans, are susceptible to giardia-related diarrhea. Because so many subspecies of the giardia exist, veterinarians and physicians are uncertain which of them can jump between species. I just assume that they all can.

In cats with diarrhea, the presence of giardia is quite easy to diagnose. Veterinarians are likely to miss the parasite if stool samples are floated in standard flotation solution. There are veterinarians who claim to be able to identify giardia cysts microscopically when they are present, but I am not one of them. But when a drop of the stool is mixed with normal saline and examined under a microscope, the wriggling organisms are distinctive and very difficult to miss. A more accurate way to diagnose giardia when diarrhea is intermittent or when their numbers are low is to use the Idexx Giardia Elisa Snap Test. It is also an accurate way to identify pets that are still shedding the organism after treatment. When giardia infection causes illness, it is because of an effusive (watery) diarrhea that leads to dehydration. In more chronic cases, intestinal inflammation that accompanies severe diarrhea can cause secondary problems such as weight loss, intestinal ulcerations and rectal prolapse – particularly in young kittens. This can be life-threatening in weak or very young kittens. A vaccine against giardia is available – but few recommend it.

There are two medications that work well in controlling giardia, metronidazole (Flagyl®) and fenbendazole (Panacur®). Cats detest the taste of metronidazole. However, most giardia infections in half-grown and adult cats will clear up within a week without treatment. The key is to keep your pet well hydrated.

Coccidia, Coccidiosis, Isospora species

Coccidia, like giardia, are single celled organisms (protozoa) that have adapted to live within your cat’s body. Virtually all cats encounter this organism sometime in their lives. In animal shelters, coccidia organisms are found in up to 8% of the stool specimens of admitted animals. Undoubtedly, many more than 8% are infected. Like most parasites, coccidia go hand in hand with poor sanitation, crowding and stress. As cats mature, the incidence of coccidiosis-related disease decreases significantly. Although mature cats may shed the infective stage of this parasite (their oocysts) from time to time, it almost never causes symptoms of disease. There are an enormous number of coccidia species. All are thought to be single species-specific. The ones that inhabit cats are not a threat to your health. As an example, Isospora canis, the coccidia of dogs, does not affect cats and Isospora felis, the coccidia of cats, is not a problem in dogs. Although coccidia are primary spread between cats through direct fecal contamination, flies, cockroaches, mice and other vermin that have come in contact with cat stool can potentially spread the parasite as well. Mice have their own coccidia, but that one does not infect cats.

Coccidia invade the cells that line your cat’s intestine, causing inflammation and diarrhea that is indistinguishable from diarrhea caused by giardia. Both can be present at the same time. They are only life-threatening in infant kittens and debilitated (weakened) animals where the diarrhea leads to serious dehydration and colic that prevents feeding. The parasite encysted stages (oocysts) are easy to see and identify in fecal flotation tests and after the first few days. The number of coccidia seen correlates well with the severity of the symptoms that your cat is experiencing. Coccidia transfer from pet to pet through fecal contamination and oral ingestion. It takes about a week before symptoms begin and about five weeks after symptoms subside before the parasites disappear from stool specimens. Many cats continue to shed a few parasites in their stools for long periods after recovery.Early in the diarrhea stage, stool specimens can still be negative for coccidia oocysts. Veterinarians, particularly those working in animal shelters, sometimes begin these kittens with sulfa medications intuitively. Small kittens might also need intravenous or subcutaneously administered fluids as well as medications to calm and slow intestinal contractions. TLC and supportive care for these infants is an important aid to recovery.

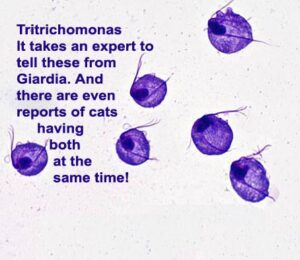

Tritrichomonas = Trichomoniasis,

This organism is a distant cousin of the trichomonas that infects humans. Tritrichomonas is another one-celled, protozoan organism with the ability to cause diarrhea in immature cats. It was only recently discovered to be a pathogen of cats. Veterinarians had known for a long time that this or perhaps a similar but distinct Tritrichomonas infected swine and cattle. When cats are affected, they often have bouts of soft stools that come and go over long periods of time. Stools produced occasionally contain flecks of blood and streaks of mucous. During bouts of diarrhea, the cat’s anus is often painful and swollen. Some sources claim that up to 30% of cats carry this parasite. Certain breeds (Bengals, Persians, and Abyssinians) might be particularly susceptible to tritrichomonads. During bouts of diarrhea, their stool odor is quite intense. Unlike giardia and coccidia, Tritrichomonas lives in your cat’s lower intestinal tract (its large bowel) – farther down than where nutrients are absorbed. So, infected cats do not generally lose weight or condition. Veterinarians are uncertain how this parasite moves from one cat to another. But a fecal-to-oral rout is most likely. This parasite is recognized through its characteristic undulations (“barrel roll motions”) made when still alive. So, they will not be seen on an ordinary fecal flotation slide where chemicals have been used to bring parasites and their eggs to the surface. When these parasites are noticed in a direct microscopic examination of your cat’s diluted stool, they are quite easy to mistake for giardia. So, if your cat has a case of “chronic or reoccurring giardia” or giardia that is unresponsive to the two medications generally used to treat it, consider having a sample sent to Davis or another RT-PCR lab for identification or utilize an “InPouch” diagnostic method. Since the same poor sanitation and environments that favor giardia favor Tritrichomonas, it is possible that your cat could become infected with both organisms at the same time. One could also easily mistake this parasite’s presence for inflammatory bowel disease. So screen those cats for Tritrichomonas too. The standard medications used to treat diarrhea and intestinal parasites in cats have no effect on Tritrichomonas. Ronidazole is the only drug that appears effective. Untreated, most cats spontaneously recover after a lengthy period of time. You can read more about Tritrichomonas in cats here.

Tapeworms

The common tapeworms of cats rarely cause health issues. You can read more extensively about them in another article of mine. (read here). In urban United States, over 90% of the cases are due to dipylidium caninum. That tapeworm moves from cat to cat through fleas. However, rural, feral and cats that spend time out of doors hunting are also subject to infection with Taenia tapeworms, particularly Taenia taeniaeformis. Tania tapeworm larva (cysticercoids) are carried by rodents. Another good reason not to allow your cat to wander. (read here)

Toxoplasma = Toxoplasmosis, Toxoplasma gondii

Toxoplasma gondii is another single-celled protozoan parasite. Unlike the many other coccidia that it resembles, toxoplasma is not at all particular which species of warm-blooded animal it infects. Its unique characteristic is that it only forms its infectious oocyte cysts in the cells that line the intestinal tract of cats. Once these oocyte cysts are expelled in the cat’s feces, they are known to remain infectious for at least 100 days when mixed with damp soil. (read here) You can read my article that is just about toxoplasma in cats here. You read a lot online about toxoplasmosis, the disease caused by this little one-celled protozoan organism when it gets into the wrong animal or a human. When it is living in the cells of the digestive tract of cats, where it belongs, it rarely causes disease symptoms. However, infected cats are Nature’s reservoir for this parasite. It’s natural life cycle is to move from cat to cat when they eat a wild rodent. Normally, it is only when the feces of cats are accidentally swallowed by humans, pets and other animals that they cause disease. Toxoplasma will however sometimes cause disease in cats that are immunosuppressed. Human exposure to toxoplasma is quite common because there are so many feral cats. About a third of the people in the world today are thought to have been exposed to it. (read here) However, it is generally only people with weakened immune systems who become ill. Most of us never know they were exposed as the immune system of our bodies quickly destroys these invaders. One exposure usually produces a solid, lifelong immunity to toxoplasma-related disease. However, once exposed, the parasite might have the ability to persist in our bodies in a dormant state. (read here)

Most shelter and randomly bred cats in North America have probably been exposed at some time in their lives to toxoplasma. But they only shed toxoplasma cysts intermittently and in low numbers. When your veterinarian observes toxoplasma cysts microscopically in large numbers in a cat’s fecal sample, it is usually a young cat or half grown kitten that has only recently been exposed. Carrier cats of any age are capable of shedding infective toxoplasmosis cysts throughout their lives. The oldest cat reported to have done so was 18 years old. (read here) The best way to avoid exposing your cat to toxoplasma is to keep it indoors, not allow it to hunt and not feed it raw meat.

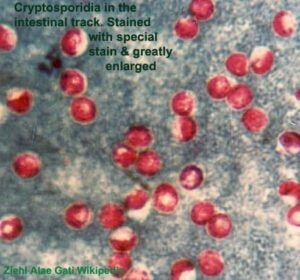

Cryptosporidium aka C. parvum aka C. felis

This coccidia-like protozoan parasite is also commonly found living in the intestinal cells of cats and other animals. There is confusion as to the differences, if any, between various strains. I treat them all as one. Cryptosporidia occasionally causes a mild, transient (temporary) diarrhea in cats. Cats become infected through fecal contamination or through consuming fecally contaminated food or water. The parasite’s telltale resistant cysts (sporulated oocysts) are hard for your veterinarian to identify in feces because they are exceedingly small. When cryptosporidium is suspected, it is best to confirm it with a laboratory PCR test. Cryptosporidium can transfer to humans. The disease, Cryptosporidiosis, is primarily a concern for cat owners and others with weakened immune systems (immunocompromised). Cats are not a particular threat, as there are many other ways you might become infected with this parasite. (read here) In humans with healthy immune systems, it often results in no symptoms at all. In another percentage of people, cryptosporidium causes diarrhea, cramps, and nausea and even a fever, all lasting up to two weeks. (read here)

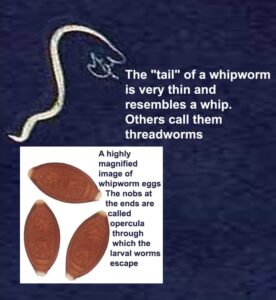

Whipworms Trichuris

T. vulpis whipworms are the most common ones that infect dogs. A different species of whipworm, T. serrata, (aka T. felis?) is the most common one to infect cats. (read here) Even when present, these parasites are hard to diagnose by common animal hospital methods because they only pass their eggs intermittently. These parasites rarely if ever produce symptoms in the cats that harbor them. In dogs, whipworms have been associated with symptoms that mimic Addison’s Disease, a deficiency in cortisol hormone due to adrenal gland disease. I do not know of any reported cases of that occurring in cats. Cat whipworms are probably of no threat to humans.

Are Parasites A Concern When I Feed My Pets Raw Meat?

One of the reasons us humans have evolved to eating cooked meat is that it lessens our exposure to disease. Parasites and bacteria are continually looking for good ways to get passed on to a new victim. Hitching a ride through the food supply is a very effective means of getting around. Despite what you read on the internet or see in pet food commercials, domestic cats and us humans have evolved together over the last 5,000+ years to thrive on cooked diets. Just like you, your cat will do quite well when its nutritionally balanced diet has been cooked. (read here) What goes into industrially manufactured cat foods, however, is an entirely different matter. (read here) A few of the parasitic and bacterial diseases associated with consuming raw meat are tapeworm disease, trichinosis, pathogenic E.coli, toxoplasmosis and listeriosis and salmonellosis, along with many of the other parasites I already mentioned. That is why I suggest that all the ingredients you feed to your cat be heated to a temperature that makes them safe for your pet. If you feel you must feed raw meat to your cat, feed it supermarket meat that is for sale for your consumption. Many, but not all, of the larger parasites that pose a threat to your pet’s health are also destroyed by freezing (20 days @ -15 C or 6 days @ -30 C). But those temperatures cannot be relied upon to kill all dangerous bacteria. (read here) I do not know of any beneficial health reasons a cat owner would want to feed a raw meat diet to their cat. The latest trend is to sell industrially prepared refrigerated diets for cats. They offer no nutritional benefits to your cat – only more opportunities for contamination.

What Are The Medications Veterinarians Us To Rid My Cat Of Worms?

Piperazine

Piperazine

Piperazine, an over-the-counter product, has been on the market since 1916. It is still on pet store shelves and big box isle sold as Hartz Ultra Guard™. Veterinarians are unlikely to dispense it to your cat or your dog. All wormers that contain only piperazine as their active ingredient are effective only against roundworm and pinworms (cats don’t get pinworms) and must be given several times to expel all of them. That is because piperazine will only eliminate roundworms that have reached your cat’s intestine after their long journey through its body. There is really no reason to give this drug to cats because cats that have roundworms quite frequently have hookworms too, and piperazine has no effect on hookworms. If used alone, it must be given multiple times until all the immature parasites have finally matured in your cat’s intestines.

Pyrantel Pamoate/Nemex®/Strongid®/& generics

Pyrantel is a great, safe product many veterinarians use to remove both roundworms and hookworms. You can also purchase it over the counter and is relatively inexpensive. It is easy to administer since its taste is usually acceptable to cats. At its correct dose, it is safe to give to pregnant and very young animals. But like piperazine, it acts only in the cat’s intestines. So, one dose is unlikely to remove immature roundworms and hookworms. It is the same medication used to remove pinworms from children and adults.

Fenbendazole/Panacur®

Fenbendazole kills many more species of parasites than pyrantel pamoate given alone. It is a better choice when diarrhea is suspected to be due to intestinal parasites, but the identity of those parasites is unknown. Three consecutive days of treatment are usually required. It is labeled for dogs, but it is frequently dispensed to cats.

Praziquantel/Droncit®

This medication, praziquantel, kills only tapeworms. It is extremely effective in doing so. It can be given orally or by injection. I prefer to inject this drug because then I am certain the pet did not spit the pill out or vomit it later. It should not be given to kittens under 4 weeks of age and I use it cautiously in debilitated animals of any age. Praziquantel/pyrantel pamoate/febantel (=Drontal Plus®, etc.) IS NOT APPROVED FOR USE IN CATS. This dog formulation kills a wider variety of intestinal parasites than Droncit®, and the febantel portion is particularly effective in killing whipworms in dogs. But as of the writing, in the United States at least, I do not believe that febantel is approved for use in cats because cats do not metabolize febantel the same way dogs do. Also, the pyrantel portion of the dog tablet is too low a dose for cats. Approved Drontal® for cat tablets contain no febantel.

Epsiprantel/Cestex®

This medication, epsiprantel, like praziquantel, is also very effective against tapeworms. It appears to be equally effective (100%) as praziquantel in killing tapeworms.

Ponazuril/Marquis Paste®

Some shelters have experimented with the use of ponazuril in pets to treat coccidiosis – related diarrhea. It is approved only for use in horses. Its chief advantage over other products is its low per-dose cost per cat. Unscrupulous puppy and kitten mills producing for the pet trade sometimes us this product to control coccidiosis as a substitute for good sanitation. I have no experience using it.

Metronidazole/Flagyl®

Metronidazole is used to control giardia and, occasionally, to control bacterial overgrowth that accompanies other parasite and bacterial infections. It tastes horrible and often causes cats to foam and drool. It is best given in capsules or coated tablets or wrapped in butter or cheese.

Sulfadimethoxine/Albon®

This sulfa medication is given to control coccidiosis and bacterial infections. I have not noticed that kittens rid themselves of coccidia any faster when given this medication; but I sometimes prescribe it for coccidiosis to prevent additional intestinal complications and to deal with concurrent health issues.

Ronidazole

Ronidazole is one of the few medications effective against tritrichomonas in cats.

What Can I Do To Be Sure My Cat Never Gets Worms Again?

Monthly Topical Or Oral Parasite Preventatives

Sanitation and avoidance might not be enough to prevent intestinal parasite exposure. In those situations, keeping your cat on a monthly flea/tick prevention product that also contains a medication active against intestinal parasites is a good option. That is particularly true if you cannot confine your cat indoors for one reason or another, or if many cats rotate through your home. The products you see in the composite photo above are only safe – when cat-use is listed on the product’s label, and you see a cat’s image on the package. (read here) To be safe, you must not exceed the correct dose for your cat’s weight. When that is the case, these product have the nod of the FDA, VDD, EMA or the TGA. If a particular parasite species is a problem, your veterinarian might suggest one of these products over another, depending on which ones your veterinary hospital has available, the parasites most common in your area and the degree of drug resistance that those parasites might have already attained in your area.

Other Parasite Prevention Advice

Your cat relies on your judgment to prevent its exposure to parasites. If you have read this far, you already know that many of these intestinal parasites enter your cat through its mouth as infective eggs, cysts, or larva that have exited in the stool of some other infected cat. If you minimize your cat’s exposure to areas where this transfer is likely to happen, you will minimize your pet’s chances of contracting parasites.

So:

Don’t let your cat run loose outdoors. Indoor-only cats live considerably longer and remain in better health than in-and-out cats due to the various health hazards they encounter in the great out-of- doors

Don’t let your cat run loose outdoors. Indoor-only cats live considerably longer and remain in better health than in-and-out cats due to the various health hazards they encounter in the great out-of- doors

Don’t bring additional cats of unknown parasite status into your household until they have had a health checkup from your local veterinarian, have been wormed several times and their fecal and virus status is confirmed to be negative. Vaccinations are unwise at this time. Animal rescues do their best. But they can never be relied upon to perform those tasks adequately. Seller-generated health certificates and CFA certificates mean very little. Until new arrivals have been examined by your vet, isolate them to areas of your home not accessible to your current cats. Tend to their daily needs last, not first.

Don’t bring additional cats of unknown parasite status into your household until they have had a health checkup from your local veterinarian, have been wormed several times and their fecal and virus status is confirmed to be negative. Vaccinations are unwise at this time. Animal rescues do their best. But they can never be relied upon to perform those tasks adequately. Seller-generated health certificates and CFA certificates mean very little. Until new arrivals have been examined by your vet, isolate them to areas of your home not accessible to your current cats. Tend to their daily needs last, not first.

Hire pet sitters that come to your home rather than boarding your cat at catteries, cat resorts or animal hospitals. Cats hate them.

Hire pet sitters that come to your home rather than boarding your cat at catteries, cat resorts or animal hospitals. Cats hate them.

Don’t take your cat to cat shows or cat get-togethers. Only cat owners enjoy cat shows. Their cats certainly don’t.

Don’t take your cat to cat shows or cat get-togethers. Only cat owners enjoy cat shows. Their cats certainly don’t.

Use covered cat litter trays, clean and empty them frequently. That won’t prevent parasite transfer in single-cat households. But it protects other family members.

Use covered cat litter trays, clean and empty them frequently. That won’t prevent parasite transfer in single-cat households. But it protects other family members.

Cleaning Up Your House And Yard

Some parasite cysts and eggs, such as hookworms and giardia, do not have protective coatings. Those eggs die in a relatively short period when they are exposed to sunshine, warmth, and drying or bleach. For those parasites, a good house cleaning and airing out are sufficient. Put all washable things through a hot-water washer-dryer cycle and let them sit for a week if possible before using them again. Fill a plastic trash can in your garage or back porch with a 1:20 solution of household bleach and let any bleachable items, such as food and water bowels soak in it for an hour. For bleach to work, you need to remove as much accumulated grime as you can before soaking. Bottles of bleach lose strength over time. Check their expiration dates. Don’t inhale bleach.

Vacuum your rugs and then throw away the vacuum cleaner bag. Other parasites, such as roundworms, whipworms, and coccidia produce eggs and cysts that are much more difficult to destroy. Common disinfectants have no effect on them – although all are killed by live steam. Their eggs and the grime that contains them must be physically scraped off. That is a lot of work. But it can be done when surfaces are smooth and washable. It is next to impossible on porous surfaces or on items that cannot be washed or heated without damaging them. It is possible to encapsulate these eggs and cysts with a new coating of paint. Outside, it is possible to add a fresh inch or two layer of topsoil over contaminated areas of your yard. Even though sunshine and warm temperature do not kill the resistant eggs of roundworms and whipworms immediately, they probably lessen the period of time they survive. I mentioned that bleach, diluted to a reasonable strength, will not kill roundworms. But it is said to remove the sticky coating that makes these eggs cling to objects such as shoes or paws and to make physical cleanup easier.

If your yard is unfenced, consider fencing it to keep out stray animals. If you must feed your pets outside of your house, remove all food at night. Your nighttime visitors will be rats, mice, raccoons, and opossums.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.