Cancer In My Dog – How It Will Affect My Dog And How It Will Affect Me?

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Entyce Appetite Stimulant For Dogs

Entyce Appetite Stimulant For Dogs

In 2023, the AVMA reported that there were over 77 million pet dogs in the United States. It estimated that somewhere between one in three and one in four of these dogs would face cancer sometime in their life. So, in 2023, I thought it was time that I updated the information that used to resided on this webpage.

The causes of cancer in dogs are as complicated as they are in us. Because our dog’s lives, counted in human years, are so much shorter than ours, they face cancer issues much sooner. The likelihood that your dog will develop a serious tumor increases sharply after it reaches the age of 7 to 9. But once your dog reaches the age of 10, that likelihood begins to be overtaken, and then surpassed, by other serious canine health issues – things like heart disease, organ failure or mental decline. Statistics like these are also likely to over-estimate the likelihood of cancer in dogs. That is because many dogs rarely if ever visit animal hospitals, and the ones that end up visiting veterinary school and specialty clinics that provide these statistics were referred there by your local veterinarian, who was already suspicious that a tumor was the underlining cause of your dog’s declining health.

The legacy California Animal Neoplasm Registry began cataloging canine cancers in 1963. That, and other old studies, indicated that approximately 15-30% of dogs were diagnosed with cancer during their lifetimes. In those days, tests that identified cancer or determined the dog population were more primitive than they are today – so many dog tumors were probably missed. Statistics also vary depending on where you and your pet live. In Swiss dogs, skin tumors were the most common tumor (37%), followed by mammary gland tumors (23.6%), soft tissue tumors (35.1%), and tumor of lymphocytes (13.2%). (read here) A review of 3,000 British dogs found that their average age at their passing was 11 years and one month. Nearly 16% of their deaths were attributable to cancer – twice as many as were due to heart disease. Only 8% of those 3,000 dogs lived beyond the age of fifteen. The longest living three breeds were Jack Russell terriers, miniature poodles and whippets. (read here)

The Agria Pet Insurance Company is the oldest, most experienced insurer of animals in the World. They began insuring Swedish farm horses and milk cows in 1890. Currently, their main office is in the UK. Today, they primarily insure dogs and cats. To survive that long and continue to make modest profits on their policies, Agria had to know quite accurately how long your pet was likely to live, what health issues it was likely to face, and how much treatment of those issues was likely to cost. As I write this, you can’t buy Agria polices if you live in North America. But in 2021, Trupanion Pet Insurance of Seattle, Washington lured Agria’s UK CEO over to America to work for them. Agria found that 5 causes accounted for 62% of their insured British dog’s deaths: 39% were due to cancer, 17% due to accidents, 13% were due to motility issues, 8% were due to heart failure and 6% were due to “neurological issues”. Mammary gland tumors, lymphosarcoma, liver tumors and lung tumors lead the list of cancer types, in that order. Boxers led the list in cancer diagnosis, followed by golden retrievers. In dogs less than 10 years old, Irish wolfhounds and Bernese mountain dogs led the list in cancer diagnosis. (read here)

Decision Bias

Bernard Rollin, the man in the photo, was a friend of mine. He was a professor of philosophy at Colorado State University. He taught me that sometimes the most loving decision you can make for your dog is the one that will hurt you the most. He sent me one of his articles about decision-making for cats in their twilight years. If he also wrote one about dogs, I do not know. But’ I’ll send you his cat article if you ask me. When you discuss your dog or cat’s treatment options with your favorite veterinarian, remember that he/she is obligated to mention all advanced treatment options available at specialized veterinary facilities. But that doesn’t mean that she or he would choose to avail themselves of those sophisticated chemo and surgical services if it was their own dog that faced aggressive cancer. You will have to read between the lines of what your vet tells you when announcing bad news. Mannerisms often tell you more than the words do. Specialty, privately owned veterinary hospitals now exist in most US, European and Asian urban centers. No doubt, they have access to highly competent veterinarians and sophisticated equipment that your local general practice veterinarian doesn’t have. However, the commercial ones are all profit-driven corporations, with salaries to pay and stockholders to please that requires a steady stream of new clients. The college-associated ones are intent on research, writing journal articles and teaching the precepts of oncology to their students. Empathy for dogs and dog owners is not a requirement. The online presence and client brochures of all of them are always upbeat – and just as accurate as the rest of the advertisements you are subjected to online. When you consult a veterinary oncologist, he/she is likely to suggest chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. If you consult a veterinary surgical specialist, that person is likely to suggest a surgical cancer option for your dog. It’s just human nature to be enthusiastic and upbeat about what you do.

What Are The Most Common Tumors Of Dogs?

When your dog has a visible or feelable lump, raised blemish or area that will not heal, the most common way veterinarians determine what it might be is by doing a needle biopsy. The second most common way is by taking a small snippet of tissue (biopsy) or the entire mass and sending it to a central laboratory to be viewed by a trained veterinary pathologist. Even experienced veterinary pathologists sometimes differ in their interpretation of the degree of malignancy of a cancer and even the tumor type. When I worked for the NIH, I would occasionally submit the same tumor to two different pathologists and receive differing interpretations.

Papillomas

Papillomas are the most common skin growths that veterinarians encounter on dogs. They are akin to warts, and many would not consider them tumors at all. The vast majority on dogs are not malignant. They cause no damage, beyond being easily nicked or worried into bleeding by your dog as it grooms reachable areas, or by groomers when they nick them with clippers. When they form on the edge of your dog’s eyelid, they do need to be removed promptly because they can irritate your dog’s cornea. Papillomas are most often small, soft, oval or cauliflower-like projections that become common as your dog ages. They are commonly on its face – particularly after your dog begins to develop graying hairs on its face and ears and paws. But they can occur on its trunk and extremities as well. Papillomas can also develop on the lips. Tumors actually in your dog’s mouth, oral tumors, tend to be considerably more serious issues. Papillomas are due to previous infections with one of the many canine papillomaviruses that occurred in your dog’s youth. (read here) They occasionally appear as flattened plaques (atypical papillomas).

For simple skin tumors such as papillomas, removal using local anesthesia and/or injectable products such as dexmedetomidine, or calming agents such as etomidate, the cost in 2023 can vary from $180 to $475 or more depending on their number and location. Costs are highly variable, depending on the surgical time required to remove them completely. Costs are likely to be considerably higher when a specialty surgeon, rather than your neighborhood primary care veterinarian, performs the procedure. Your local veterinarian should be easily able to freeze them off (cryosurgery). At the NIA, I routinely froze them off of our geriatric beagles with a Q-tip dipped in liquid nitrogen.

Lipomas – Fat Tumors

The next most common type of cancer in dogs are probably lipomas. They occur just under the skin. They are soft, and usually have the consistency of a baggy filled with water. Lipomas are never life-threatening. They are benign. They often occur in multiple locations. These tumors will usually shrink, but not entirely disappear, if you put your pet on a lower calorie diet. In 2023, Market Watch quoted the average cost of lipoma removal surgery for dogs at $200 – $500. But considerably higher (>$1,000) if the tumor(s) had projections deep into muscle masses, such as near your dog’s armpit or groin, or if your dog has other disabling health issues that require special precautions (“a poor surgical candidate”). In those situations, pre-surgical workups and tests of various sorts might be required. Lipomas rarely arise before your dog reaches middle age. They are easily confirmed to be fat tumors by the presence of many fat globules seen microscopically in a needle aspirate exam that your local, primary care veterinarian can perform at the office. As I mentioned, overweight dogs are more susceptible and, for unknown reasons, plump Labrador retrievers, schnauzers, dachshunds and cocker spaniels seem to develop more than their fair share of them. Unless they are making your dog uncomfortable, many pet owners and veterinarians simply disregard them as no more than cosmetic blemishes. No need for overweight shaming, I once hinted at a diet for a roly-poly. lab with lipomas. The owner replied, yes, he’s fat, but he wears it well.

There is said to be the very slight possibility of a rare malignant fat cell tumor. It is called liposarcoma. I have never seen one. If and when they occur, it is not just beneath your dog’s skin. It is in its liver or another internal organ. The cells of those tumors show some similarities to fat cells, hence their name. They are not thought to arise from superficial, under-the-skin lipomas.

Mast Cell Tumors

Mast cell tumors are a common, and potentially serious, superficial tumor of dogs. Besides being limited to occurring in your dog’s skin and just below it, these tumors have no particular shape or color that would let your veterinarian identify them by site or feel. Mast cell tumors are sometimes called mastocytomas. Your dog’s normal mast cells originated in its bone marrow, after which they move through its body through its blood stream to eventually take up residence in most areas of its body with their highest concentration in strategic areas that interface with the dog’s environment, its skin, its lungs, and its intestinal lining, where they act as sentinel cells of pathogen invasion. In allergies and anaphylaxis, they mistake unimportant things they encounter for threats. We don’t know how long mast cells live in dogs once they take up their permanent residence, but in rats mast cells live about 12 weeks. However, when one of the mast cells divides into a mutant clone, that clone becomes immortal, with the ability to metastasize. Some are more likely to do that than others. Veterinary pathologists judge that ability based on how rapidly the cancerous cells within the tumor appear to be dividing and the degree with which the mast cells are invading the normal tissue that surrounds them (their aggressiveness). When judged minimal, veterinary pathologists call them “low or lower grade”. When judged “high grade” they are the most dangerous kind. The higher the grade, the more of the tissue surrounding the mast cell tumor needs to be surgically removed, in the hope that every last cancerous cell is eliminated. Complete removal is particularly challenging for your veterinarian when these tumors form on your dog’s legs, neck or face because there is very little excess skin there to close the gap after the tumor has been removed. In some cases, a skin graft will be required to do that, in others, multiple surgeries. Since your veterinarian has no accurate way to visually tell health tissue from already invaded tissue, most remove as much surrounding tissue as your dog can spare and then go on to suggest chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Veterinary oncologists and surgical specialists are likely to recommend that the tumor be biopsied before the actual surgery is performed, in order to gauge its aggressiveness. If deemed aggressive, they will probably want to sample the regional lymph nodes that drain the tumor area and your dog’s lungs and liver for escaped tumor cells as well. One of the things you will notice in the unfortunate cases where this has already occurred is cancer cachexia, weight loss, energy loss, and apathy. For reasons unknown, golden retrievers have a genetic predisposition to mast cell tumors. (read here) Boxers, Boston terriers, pugs, and bulldogs are high on the list as well. Some say that mast cell tumors make up ~20% of canine skin tumors.

What Might Mast Cell Tumor Surgery For My Dog Cost?

In 2023, the Veterinary Oncology Department’s website at NCSUCVM stated that they charge ~$2,000 – $4,000 for the actual surgical removal of superficial tumors from dogs at their facility. But that later additional charges were unpredictable. You already understand why that would be. If post-operative radiation treatment is required, that runs $4,500 – $6,000 more. If it is already too late to remove the tumor, radiation therapy just to slow the tumor’s growth runs ~$1,000 – $2,000. Chemotherapy runs $300 – $400 per treatment or $300 – $650 per month, depending on your dog’s weight. Medications given to keep your dog as comfortable as possible when surgery is not an option run $30 – $200 per month (palliative treatment). The UWCVM is more coy about revealing how much they charge. Their website states, “Cost estimates are based on individual appointments and overall cost is dependent on patient response and does not include additional supportive care or hospitalization, if required“. Embrace Pet Insurance reports that mast cell tumor removal claims are highly variable, but average $500 to $1,000 when performed by your primary care veterinarian. However, they note that if a board-certified surgeon or oncologist does the surgery, the cost will likely increase by two-to-five fold. That if radiation therapy is also recommended, it generally costs $4,000 to $10,000 more. To the best of my knowledge, Embrace’s most expensive canine policy ($30 – $40/ month) in 2023 pays a maximum of $650 per year. You would have to call them and ask. Their tumor coverage ends when your dog turns 15 yrs. In 2023, Agria Pet Insurance in the UK, for example, has no dog age limit, but limits yearly coverage to £12,500 ($16,057.50) per year. . Since Embrace might have published this data in an effort to motivate people like you to purchase their insurance, those figures might be on the very high end of what you will be quoted by competent veterinarian specialists in your area. At the very bottom of this page, I will add your experiences and costs with any of these tumor types in your dog if you provide them to me.

Although not a traditional chemotherapy option, oral medications, Palladia® (toceranib) and masitinib are approved to treat mast cell tumors in dogs. They are generally given at home three times a week or every second day. Ohio State, and Michigan State Universities veterinary schools dispenses Palladia® as a first-line treatment for mast cell tumors that exhibit a particular gene mutation (KIT) and also to dogs that have failed other therapies, have large tumors that cannot be surgically removed or are concurrently receiving radiation therapy as part of their treatment plan.

Mammary Gland Tumors

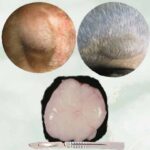

The particular tumor in the photo above was in a 14 yr old female Labrador Retriever. It was about eight centimeters in diameter. Histopathology determined that it was a carcinoma. Mammary gland tumors are the most common tumors veterinarians encounter in unspayed, female dogs, or dogs that were spayed later in their life.They are said to represent 42% of all tumors in female dogs. Mammary gland tumors are very rare in male dogs. That is because a dog’s ovaries produce the majority of its progesterone, and progesterone is a driver (stimulator) of mammary gland cancer in dogs and in us. Approximately half of these tumors in dogs are malignant. About the same as in humans. And as with human breast tumors, the majority of these tumors in dogs are adenocarcinomas (gland tissue tumors). Even when malignant, most can be successfully removed from dogs, although a few advanced canine cases require follow-up chemotherapy. For reasons unknown, miniature poodles, dachshunds, German shepherds, cockers and other spaniels lead the list in developing mammary gland tumors. Fat dogs appear to be a bit more at risk.

The first sign you are likely to notice is an oval, small, firm lump near one of your dog’s nipples. When present and squeezed, these lumps are rarely painful. Your vet will also check for any lumps in the lymph nodes that drain that, and nearby mammary glands. Laboratory blood tests in these early cases rarely reveal any changes associated with these tumors. In advanced cases, where cancerous cells have spread to internal organs, laboratory blood tests might hint as to which organ(s) the tumor has spread to. As with all tumors, biopsies, sent to a veterinary pathologist, will tell your veterinarian the specific tumor type and its degree of malignancy. It is always safest to have your veterinarian remove all of your dog’s mammary glands once cancer has begun in one or more of them – unless other serious health issues preclude that. A “lumpectomy” might be a wiser choice if your dog is elderly and likely to pass away due to other health issues before new or residual breast tumors become a problem. You, not your veterinarian or some specialist, is the best judge of that. Seek a second opinion is also a wise choice. Most vets don’t take that personally. According to the ACVS, spaying your dog after a mammary gland tumor has been discovered is controversial. I suppose that if your dog has no other serious health issues and is still in its younger years, I would recommend it – but never at the same time as the tumor surgery. Post surgical chemotherapy or radiation treatments are rarely recommended.

What Might Mammary Gland Tumor Surgery For My Dog Cost?

NCSUCVM estimates the cost for mammary gland tumor removal at $3,000 – $5,000, depending on location and extent of disease. However, if just the existing small lump(s) are removed surgically at your local animal hospital, the cost is likely to be closer to $550 – $750. One Florida surgical specialty clinic in 2023 advertises an “all-inclusive fee” for mammary gland tumors in dogs weighing less than 22 lbs of $1,930.00 per quadrant (4-5 adjacent nipples?) and $2,130 per quadrant if your dog weighs over 22 pounds. For each additional quadrant, they charge $400 extra.

Soft Tissue Sarcomas and Carcinomas In Various Locations

There are more than 80 varieties of soft tissue sarcomas. Sarcoma tumors can spontaneously occur anywhere in your dog’s body. “Soft tissue” sarcoma types exclude those that form in your dog’s bones (osteosarcomas and, chonrosarcomas) and those that arise from your dog’s blood, lymph nodes or bone marrow. Carcinomas are similar, but they only form in cells that line your dog’s gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, or coat the outermost layer of your dog’s internal organs, or arise in its skin. Basal cell carcinomas, due to over exposure to sunshine, are the most common of all human cancers. But dogs, being furry, rarely develop them. On the rare occasions that they do, it is generally on the unfurred bridge of their nose, ears or eyelids.

Transitional Cell Carcinomas

The most common cancer that occurs in the bladder of dogs is a transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). Dogs of advanced years are the ones most likely to develop them. By the time it is discovered, your dog is most likely having difficulty urinating, urinating more frequently than normal and in smaller individual amounts, or passing blood in its urine. By that time, it is usually a high grade, invasive (malignant) cancer. Initially, your veterinarian might have diagnosed the problem as a UTI or prostate issues, dispensed antibiotics and hoped for the best. We all do. Compounding the diagnostic problem for your veterinarian, in their earlier stages, TCCs are easily missed on x-rays or ultrasound examinations (early on, they are not very radio-opaque). Advanced TCCs can rarely be cured surgically – at least not in ways that would preserve your dog’s ability to urinate normally. For unknown reasons, Scottish terriers, West Highland white terriers, dachshunds, and Shetland sheepdogs lead the list in developing this type of urinary tract tumors, but only slightly so. Because surgery is rarely if ever curative, your vet might suggest a course of chemotherapeutic drugs. Those medications appear to extend the lives of perhaps 40% of the dogs with TCCs that receive them. When they are effective, the improvement might last for a number of months – never years.

Other carcinoma tumor forms are more commonly found in the mouth, lips, nose, ears or on your dog’s tongue. The majority of them are malignant. I tell you about a common one, fibrosarcoma, farther along by it is only one of many carcinoma types. All of them are particularly difficult for veterinarians to surgically remove in their entirety. That is because so many delicate structures exit in those cramped areas. And because these tumors have often already migrated into the facial or jaw bones, complete removal is often impossible. So most vets who attempt this surgery will suggest radiation therapy subsequent to surgery or suggest only radiation therapy. Complete cures are very rare. Squamous cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, fibrosarcomas and melanomas are all in this problematic group. Few dogs develop these cancers before they reach the age of 7 or 8 yrs.

Hemangiomas and The Much More Dangerous Hemangiosarcomas Of Dogs

These are blood vessel tumors. I’ll tell you a bit about benign hemangiomas first. They are unimportant, tumors of superficial (skin) blood vessels. When they appear on a dog, it is often one with light colored skin, and in an area not covered by hair. But they also occur occasionally on a dog’s chest and belly, perhaps because those dogs enjoy sunbathing on their backs. Strictly speaking, hemangiomas are tumors – cells gone wrong, but they act more like a blemish than a tumor. Like papillomas, most are noticed by groomers or dog owners when dogs get nicked and bleed. Or, you might feel a bump in that area when bathing your dog. Hemangiomas can be any color between a dark purple and blood-red. If they become troublesome, your veterinarian can easily freeze them off (= cryosurgery). Papillomas, another benign skin tumor, can be mistaken for hemangiomas. It is common for dogs to lick and worry papillomas when they can reach them, causing the papilloma to become inflamed and red in color, at which point it could be mistaken for a hemangioma. The treatment, if desired, for both of them, is the same. We get hemangiomas too. By the time we reach 75 years old, 75% of us are said to have developed one or more – probably due to our sun exposure.

Hemangiosarcomas are an entirely different and much scarier problem. These nasty tumors of dogs are extremely invasive. Next to car accidents, hemangiosarcomas are the most common reason veterinarians discover blood to be present free in your dog’s abdomen or chest. Most veterinary pathologists do not believe that skin hemangiomas can mutate into hemangiosarcomas. The majority of hemangiosarcomas are discovered only when they rupture internally and the dog suddenly becomes extremely anemic, or passes away from blood loss. The majority of these tumors are located in a dog’s spleen. The high point (apex) of your dog’s heart is another common location (confusingly called the hearts “base“). The liver and bladder are other common locations. When a large hemangiosarcoma ruptures there, or elsewhere, it can be a natural occurrence or due to a sudden shock, such as jumping off of a chair. The dog turns pale, and its breathing becomes rapid. If the tumor is in its spleen or another abdominal organ, the dog’s belly usually rapidly enlarges. X-rays and ultrasound detect an abnormal amount of free fluid in the dog’s abdomen. When your vet passes a needle into the dog’s abdomen to determine the nature of that fluid (abdominocentesis) unclotted blood, floating free in it abdomen, is what the vet detects. Less commonly, these tumors occur elsewhere in a dog’s chest.

Even with the best emergency stabilization and surgery to stop the bleeding and remove these hemangiosarcomas, less than 10% of dogs will survive an additional year. For unknown reasons, hemangiosarcomas occur most commonly in golden retrievers, Labrador retrievers, and German shepherd breeds. Some are found by pathologists to be malignant and some are not – but the end results are the same. Dogs that develop hemangiosarcomas tend to be middle-aged to older when their problem is discovered. The medial age when hemangiosarcomas are diagnosed is ~ten years. When referred to an oncologist before or after surgery, your dog may be offered chemotherapy medications, most commonly doxorubicin. Cure rates, even with chemo, are quite low.

What Might Hemangiosarcoma Surgery And Treatment For My Dog Cost?

A 2022 article by Colorado State Veterinary School, discussed the cost of treatment for 197 dogs brought to them for treatment due to blood being free in their abdomen. In 126 of the dogs (87.5%), it was caused by a hemangiosarcoma. The cost of their first visit was 589.02- $3,613.25 with the median cost being $1,323.80. The cost of their surgery was $3,967.94 – $5,706.37 with the median cost being $4,640.75. The cost of subsequent followup visits were $518.28 – $1,497.20 with the median cost per visit being $716.50. The cost of euthanasia during the first 24 hours after admission was $508.25 – $1,275.16 with the median cost being $681.60. (read here)

Another facility, NCSVS in 2023 estimates of the cost of attempting to remove an internal hemangiosarcoma at $3,000 – $7,000. It might be considerably more if the tumor(s) are located in difficult to reach locations. Chemotherapy runs $400 per treatment, with treatments anticipated every 2–3 weeks for 4–6 treatments. The costs of chemotherapy are higher for large dogs than small dogs. Radiation treatments, when suggested, run $4,500 – $6,000. Cat scans may also be required.

Fibrosarcomas

Fibrosarcomas form when a clone of the fibroblasts that hold our bodies together (aka connective tissue) become cancerous. Unlike some of the other tumors I mentioned earlier, fibrosarcomas tend to grow slowly, and they rarely metastasize (move) to distant locations (only ~10% do). But fibrosarcomas are considered locally malignant. In cats, superficial (cutaneous) fibrosarcomas are often related to over-vaccination (read here), but that is apparently not so in dogs. Fibrosarcomas are not among the most common tumors of dogs. However, when dogs do develop them, they often form in the pet’s mouth or nasal passages where they, like nasal and oral carcinomas, are very difficult for your veterinarian to completely remove (“no clean margins“). When it is impossible to reach and remove all of a tumor, veterinarians describe the surgery as “debulking”. Removing as much of a cancerous mass as possible will hopefully make your pet more comfortable and, perhaps, extend its life. Perhaps debulking surgery will also allow a lower dose of chemotherapy drugs or radiation to be effective. Veterinarians are unsure of that, and physicians ponder the same question. When fibrosarcomas develop on a lower extremity (lower leg), amputation might be the safest solution. That is because there is so little excess skin and tissue on a dog’s lower leg to close the resulting post-surgical gap. Most dogs that develop fibrosarcomas are middle-aged or older. The average age at which they are discovered is 8–10 yrs. When the tumor is in the mouth, lips or nasal passages, secondary bacterial infections often occur. So an abnormal odor, snorting, nasal drainage, blood or drooling might be the first signs that alert you to the problem. When present on a leg, there will likely be a change in your dog’s gait (limp). Fibrosarcomas could be confused with a number of similar tumor types, e.g. oral or nasal carcinomas when in the mouth or nose, or an osteosarcoma when on an extremity. But as with all tumors, a fine needle aspirates or a biopsy sent to a veterinary pathologist should confirm the tumor’s identity. Some veterinarians believe that post-surgical radiation treatments or post-surgical chemotherapy lengthen the period that remaining tumor cells stay in remission (dormant). But we all hope it does.

What Might Fibrosarcoma Tumor Treatment For My Dog Cost?

According to Embrace Pet Insurance Company, bills from specialty surgeons and subsequent care at specialty oncology clinics can exceed $10,000. And even with aggressive surgical removal, chemotherapy and radiological treatments, they report that over 70% of fibrosarcomas recur within the first year. Because these tumors are particularly difficult to remove from the mouth and nasal areas, few veterinarians in general practice would attempt to remove them. Diagnostic costs to confirm the nature of a tumor through biopsy or aspiration cytology generally run about $500. Pre-surgical imagining of the tumor to define its borders such as thorough CT scans cost about $2,000. The actual surgery might cost $1,000 – $3,000. Chemotherapy might cost $1,000 – $5,000 and radiation treatments, $5,000 to $10,000. Since Embrace publishes this data in an effort to motivate people like you to purchase their pet insurance policies, those figures might be on the high end of what you will be quoted by competent veterinarians in your area. I will add the cost you actually paid for this, or other tumor treatments, for your dog if you let me know what they were.

Lymphomas | Lymphosarcoma Tumors

Lymphocytes are formed in your dog’s bone marrow. They then disperse to circulate in its blood stream or to reside in lymphoid tissues throughout its body, places like its lymph nodes, spleen, tonsils and peyer’s patches. Those lymphocyte-containing tissues are often at strategic locations where pathogens are likely to enter the body. (read here) In those places, healthy lymphocytes are the body’s night watchmen, sounding the alarm when a potential threat is detected. When it is the lymphocyte population of your dog’s blood that develops a cancerous clone, we call it leukemia. When it is one of your dog’s guardian lymph node populations that develops cancer, we call it lymphoma or lymphosarcoma (the words are used interchangeably, although pathologists might use the second term when they suspect higher malignancy). Lymph nodes, enlarged by cancer, are not painful to your dog. When they are the superficial lymph nodes that you can see and feel, they rarely affect your dog’s appetite or mobility until, perhaps, late in the disease. But when internal lymph nodes of the chest or abdomen become enlarged, they hinder (affect) the functions of the organs adjacent to them. An enlarged lymph node usually indicates an infection in the body part that its lymph drains from, or a lymphoma. Multiple enlarged lymph nodes in multiple areas are never a good sign. A fine needle aspirate, examined by a veterinary pathologist, should tell one from the other. Today, lymphomas in dogs are not curable, perhaps someday they will be, (read here) But fortunately, veterinarians can usually keep lymphoma in your dog in remission using chemotherapeutic medications for quite some time. Prednisone, cyclophosphamide, vincristine and doxorubicin are the most common medications used to induce lymphoma remission in dogs.

What Might Lymphoma Treatment For My Dog Cost?

In 2015, the University of Wisconsin veterinary school in an interview provided their average client costs for treating lymphoma in dogs. You will need to adjust those figures upward in line with inflation occurring during the intervening years – or just call them and inquire. If you do, let me know what their or other facilities current costs are. Their oncology department said in 2015 that their initial workup for a canine lymphoma patient would cost $1,000 – $2000. At that point, dog owners would spend about $5,000 on drug treatments that might extend their dog’s life for a year or two. They mentioned that to some of their clients, that expense for one year of quality time with their dog was worth it. But that, for other clients, one year simply wasn’t long enough for a uniformly fatal disease. The veterinarian giving the interview mentioned that for some clients, money was no object. Seventy of the dog owners had spent $16,000 – $25,000 driving to North Carolina State University’s veterinary school for bone marrow transplants for their dogs. How successful that was, he did not say, but NCSVS at the time claimed a 33% success rate in their canine bone marrow transplant program. NCSVS shut down their marrow transplant program in 2012. They claimed it was because staff was needed in other areas. But the fact that the word got out that several of the dog owners had to exhaust their life-saving or refinance their homes to pay their bill probably influenced that decision as well. I believe that other veterinary facilities in the USA offer dogs bone marrow transplants. Apparently, NCSVS has reactivated their bone marrow transplant program. (read here)

Bone Cancer | Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma is a tumor of the osteocytes that are the main components of your dog’s bones. About 85% of the tumors that originate in bone are thought to be of this type. They are all malignant, to varying degrees. They are also prone to spreading (metastasizing) to other areas of your dog’s body. When osteosarcomas occur, it is almost always in one of the large or giant dog breeds – dogs with a body size larger than the canine’s ancestral wolves. That extra height and body weight, pressing on joints and bone growth plates, appear to play a role in this tumor’s development. (read here) It has been estimated that 10,000 or more cases of canine osteosarcoma occur in the United States each year. (read here) The first sign a dog’s owner might notice is a limp, or abnormal hard bulge near the upper or lower of the two growth points of one of the dog’s long leg bones. On rarer occasions, osteosarcomas form at other bone and non-bone locations in the body – often at points of chronic bone inflammation. That could be the upper or lower jaw in an elderly canine with chronic periodontal disease, or even the presence of a metal bone plate that repaired a previous fracture or some other foreign object. (read here) Pressing on any of these areas usually causes the dog pain. Early cases could easily be mistaken for a torn joint ligament, a bruise, or other trauma. In advanced cases, bone fractures at the site of the tumor are not unusual. These tumors tend to develop a very distinctive “starburst” appearance, quite visible on ordinary x-rays. Because osteosarcomas tend to metastasize early, your veterinarian will want X-rays of your dog’s chest as well, to be sure the tumor has not already moved to your dog’s lungs. A pet’s lungs are the most common location for secondary osteosarcoma tumors to develop. That is said to occur in 50%−85% of the cases. Metastasis to lymph nodes, or the liver, is less common. If no secondary tumors are found, and the primary tumor is in one of your dog’s legs, amputation is usually the safest and most successful option. That is often followed by a course of chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g. carboplatin), doxorubicin, etc.). (read here) When that is not an option, radiation therapy might slow the tumor’s growth. Dogs with only a missing rear leg do quite well. But I am reluctant to amputate a front leg, particularly in one of the large or giant breed dogs. Large breeds carry at least 60% of their weight on their front legs. Compensating for the loss of a forelimb will eventually take its toll on the remaining front leg and shoulder and lead to decubital ulcers and incontinence when the dog can no longer rise.

Melanomas

For reasons unknown, these malignant tumors often occur in a dog’s mouth. When they do, they are most often malignant, infiltrative, and quite difficult for your veterinary surgeon to completely remove. Boehringer Ingelheim/Merial markets a vaccine that they claim will extend the lives of dogs in which the tumor cannot be completely removed. Their Oncept™ melanoma vaccine is a DNA vaccine. It is USDA approved for treatment of stage II to III canine oral melanoma and is also used off-label for melanomas arising in other locations and in other species. While the vaccine appears safe, the published data is mixed as to whether it provides any survival benefit to your dog, and the use of the vaccine is somewhat controversial in the veterinary oncology (cancer) community. (read here)

How Do I Keep My Dog Happy When It Has Cancer?

The way to a dog’s happiness is through its stomach. I taste everything I feed my pets. If it doesn’t have a rich, meaty flavor, it goes straight to the trash. I don’t suggest any of those phony “cancer diets” that specialty dog food companies peddle through veterinarians. I hope you or your friends never develop cancer, but if you do, is your oncologist going to go to the back room and come back with a cart full of canned or sacked food that you have to eat for the rest of your life? You’ll do a much better job cruising the meat isles of your neighborhood supermarket and preparing your dog’s diet on your stove top. When it no longer accepts what it once enjoyed, consider an appetite stimulant such as Entyce® or mirtazapine. I have tasted Entyce. If your dog shows displeasure with its taste, as I did, don’t give it. Read dog owner feedback on that product here. If your dog shows displeasure with its taste, don’t give it. Read dog owner feedback on that product here.

God gave our dogs shorter lives than us. But he blessed them with the gift of not fearing the future or dwelling on their illnesses. Unlike us, they don’t worry about the passage of time or where they will spend eternity. So, if they even consider it, they face death with considerably more peace than we do. No matter the illnesses they face, they remain happy with only your presence and your love. Veterinary medicine has made tremendous strides in delaying the death of pets. My articles are meant to explain the strategies veterinarians use to do that. But would your pet want you to do everything conceivable to extend its life? My feelings are that it probably would not. Will you be doing those things for your pet’s happiness or for your happiness? Your pet will remain happy if it has something good to eat, a loving home and the pleasure of your company. Pet’s key off of your emotions. If you are sad, they are sad. if you are at peace and accepting, they will be too.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.