What Are Feather Stress Bars?

Ron Hines DVM PhD

All Of Dr. Hines’ Wildlife Rehab Articles

All Of Dr. Hines’ Wildlife Rehab Articles

I originally wrote this article for parrot and other aviary birds. But it applies to wild birds of all types as well.

During the period that a feather is forming, the follicle that produces that feather relies on a steady stream of nutrients (the amino acids needed to build a feather’s β-keratin protein obtained from the nutrient proteins in a bird’s blood stream. (ask me for King1987) If that steady flow of food nutrients is interrupted – either by a lack of food or an disinclination to eat – the feather will no longer develop normally because the feather-forming cells that line the feather follicle can no longer produce the keratin proteins needed to form the underlying structure of the feather. When those nutrients again reach their proper level in the bird’s blood stream, feather development returns to normal.

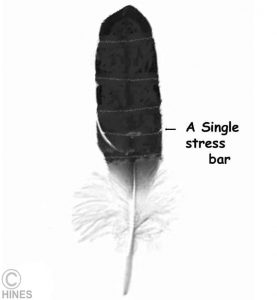

So a careful examination of a bird’s feathers gives you or your veterinarian a look back into its past. In the particular dove in the photos above, one of my volunteers apparently missed a scheduled feeding while the bird’s feathers that I am pointing to were developing. That resulted in the narrow white lines ( like a scissor cut ) present to the right of my finger. You can see that even the integrity and strength of of the feather shaft was compromised at that point. With time, those feathers will break at both locations. You can read a bit more about the problem and feathers in general here.

Whatever their cause these defective bands only form in developing feathers (“blood feathers”). They do not become very apparent until the feather has fully unfurled. When these bars occur in a bird you are hand-feeding, the most common cause is not feeding frequently enough during the day. The Feather and Beak virus , best known as a disease of cockatoos, parrots, and macaws, also causes deformed feathers. But those feather defects have a different appearance than stress bars. It is probable that that avian circovirus has the potential to affect the feathers of many wild non-parrot birds as well. (read here)

I drew the imaginary feather image above to dramatize what you might see. But remember that besides a periodic lack of feather-building nutrients, infectious diseases that wax and wane (intensify intermittently) and other environmental stresses have the ability to produce weak, imperfectly-formed feathers. But not in discrete bands similar to the ones I pictured. I cannot tell you the time period represented between each stress bar line. That depends on the particular location of the feather that is involved and the species of bird the feather belongs to. A birds, primary wing feathers are the ones that grow the slowest and also, along with its tail feathers, the ones most likely to show stress bars. In chickens, primary wing feathers in hatchlings grown to about 75% of their final length within three weeks. Then final feather growth slows and it takes another three weeks for these feathers to reach their maximum length. In turkeys, primary wing feathers are said to grow about 0.9 inches per week – with different wing feathers growing at slightly different rates. Most adult American songbirds and small raptors replace their 9 to 10 primary wing feathers once a year. But it takes larger bird species such as eagles and pelicans a disproportionately longer time to grow a full set of their replacement flight feathers – upwards of a year. Feather replacement in birds in the wild needs to be gradual. Replacing more than one flight feather on each wing at a time reduces the bird’s flight efficiency required to successfully forage, hunt and to escape its predators. (read here) The only exception are the flightless birds like penguins that experience climax molts (catastrophic molts) during which they shed all their feathers at once. The whole process takes about a month during which they do not eat, swim or move about – while the already partially formed new feathers push out the old ones all at one time:

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that Google chooses to display on this webpage helps me pay the cost of keeping this article on the Web. As you know, sites like mine that are not designed to make money are getting harder and harder to find. Best wishes, Ron Hines

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that Google chooses to display on this webpage helps me pay the cost of keeping this article on the Web. As you know, sites like mine that are not designed to make money are getting harder and harder to find. Best wishes, Ron Hines