Broken Legs In Song Birds – And How I Repair Them

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Birds with a broken leg – like the baby mockingbird in the top photo – will often use the wing on the same side as their leg injury as a crutch to help support and steady themselves.

There are innumerable ways wild birds suffer leg bone fractures. No two are exactly alike in their origin or best treatment. In youngsters, falls from the nest are the most common. Becoming tangled in the nest material is another. Predatory birds sometimes pick young birds out of their nest and carry them off by a foot. Where I live, grackles are infamous for that. The repair of fractures in adult birds is considerably more challenging than the simple method I describe in this article for baby birds. The skeletons of adult birds are already fully calcified. So, their bones are more brittle and prone to compound fractures consisting of many small pieces (comminuted). Fear, stress and struggle in adult wild creatures is always an issue wildlife rehabilitators must deal with.

Adult avian wings and leg bones, being hollow and fully calcified, break with razor sharp edges that quickly slice through adjoining ligaments, nerves and muscle as the perplexed bird struggles to walk or fly. When portions of the bone protrude through the skin, they are always bacterially contaminated. So, sometimes I must removed devitalized portions and devise implants to bridge the missing gaps. Many of the larger species of birds that the Texas game wardens bring me have been shot while perched on telephone poles and lines. I repair all of them when I can, but many have no future hope to be free again in the wild. I am always looking for good homes for these creatures. Permits can be quite hard to obtain, but Let me know if you might accept one.

Which Injured Birds Offer The Most Hope?

Immature birds – like the baby mockingbird in the top photo – with a simple leg fracture have considerably more hope for a successful release into the wild. “Simple” fractures do not mean that they are simple to repair. Veterinarians and physicians classify bone fractures as “simple” transverse (only one fracture line), “compound” (pieces protruding through the skin), “comminuted” (more than two pieces or fragments), greenstick (incomplete fractures) as well as by their angle (transverse, oblique and spiral). Because the bones of these baby birds are still quite soft, they tend to have simple fractures or greenstick incomplete fractures that heal rapidly at whatever angle the creature rests its limb over the coming weeks. The secret is to keep the bone sections aligned properly during that healing process. But some of these birds only get to me after their fracture has healed at bizarre angles. Those I have to re-fracture, position them properly, and add supports that allows the bone to heal in correct position. Sometimes it takes up to four surgeries to do so because the bones and joints have distorted to deal with the forces of gravity and because surrounding muscles and ligaments have shortened in their length. Domestic birds raised on slick surfaces face similar distorted bone issues. You can read about that problem, splay leg, here.

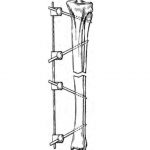

I hope that the photos below will speak for themselves. If they don’t, you can always send me an email and I will try to provide further instructions. I use stainless orthopedic steel rods (“bone pins”) placed within the hollow centers of avian the bones when I am working on larger patients like pelicans. But to stabilize the fractures of diminutive songbirds with even a very small intramedullary bone pin usually requires the pin(s) to pass through a joint. That has the potential to causes permanent joint damage. So, I have occasionally constructed tiny “Kirschner apparatuses”:

Baby songbirds grow so rapidly. At young ages they have remarkable ability to surmount (heal) fractures if you can just keep the bone portions in proper alignment for a short time. That would never happen in the wild. It is always a good idea to purchase a small precious metal scale like the one in the photograph above. These scales are inexpensive when purchased on Amazon or eBay. The mockingbird in the top photo weighed 20.7 grams the day I applied its splint. I weighed the chamomile tea box before I put him in it (14.72 gms) and again with him in it (35.42 gm). Eight days later the mocker weighed 38.2 grams. Along with my scales, I keep some white children’s socks pre-weighed and marked. Struggling birds placed on the scale within a sock calm down, sits still, and eliminate the need to weigh boxes.

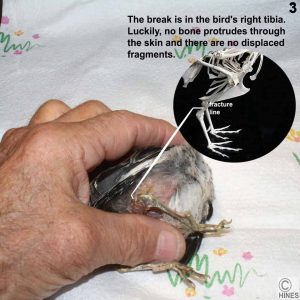

Photo 3 shows the location of this particular fracture. The break was through the lower section of its right tibia. It was fortunate that no sharp fragments of the fracture penetrated through the skin. Birds at this tender age have less calcium in their bones than adults. So, they are much less likely to end up with bone fragments that cut through surrounding tissue (ligaments, nerves and blood vessels) as they struggle. Because the bones of adult birds must be hollow to save weight, the leg and wing bones are actually harder (more calcium/more brittle) than those of mammals and more likely to end up with knife-like edges when they break after maturity.

Photo 4 is a second photo of the fracture on the day the bird arrived. I drew a yellow arrow where the break had occurred. Because of that fracture, the leg just dangles uselessly. The accident that caused it must have occurred a day or two earlier because you can see that the mockingbird had already abraded its other (left) hock joint and the toes of the left leg are already beginning to grow out of alignment (crooked) to compensate for the new way the bird supported itself on one leg and a wing.

I didn’t use the pliers in photos to form the wire loop around a syringe. It is just something I used to support things while I took the photographs. You can just see the tip of the “bull-nosed” surgical needle holders that work much better for me in bending orthopedic wire. It shows complete in photo 5. However, simple mechanic’s needle nose pliers are also satisfactory. Team up with a mobile hospital surgical instrument repair person in your area as a source of surgical instruments. When hospital instruments are discolored or have minor defects that do not preclude their use, they are usually discarded as not being worth the cost of repair or as presenting legal liability issues.

The red arrow in photo 7 shows the path that the bird’s leg will pass through when the splint is in place. It is called a modified Thomas splint. The yellow arrow shows the point where the fracture will be once the splint is applied. The blue arrow shows the point that will be just under and supporting the “palm” (underside/plantar/sole) side of the foot.

Regarding photo 8: A base layer of Tegaderm™ adhesive film is optional but quite helpful. However, it is as sticky as flypaper and often takes more than two hands to apply properly without a lot of excess wrinkles and folds. These days I often work alone. 3M Tegaderm™ and repurposed products like Medline Suresite™ or stoma port surrounds are all extremely sticky, floppy and quite hard to work with without those extra hands. But they stick to the unfeathered skin of birds considerably better and with less skin irritation than the hospital-grade bandage tape which I apply over them for extra support and protection. Many immature birds require only the stiffness of that tape for their leg to heal satisfactory. As the bird’s skin surface naturally sheds (desquamates), Tegaderm™ and Suresite™ come loose by themselves at about the time I want them to.

In photo 9, eight days have now passed since the Thomas splint was first applied. You can see the increased blood supply at the fracture site as the upper and lower portions of the bone attempt to unite and become stable. I check these birds every day – often removing the previous tape to be sure blood is flowing adequately through the leg and that the positioning is just right. Improper tape pressure quickly causes skin ulcers (“bed sores”) or worse. As an avian limb bone heals, the new bone is primarily deposited on its outer surface – not within the bone’s hollow center. The new bone (callus) begins as a large blood clot. With time, cells that produce cartilage (chondrocytes) arrive to stiffen the area. Since the original clot was large, a firm lump begins to form. You can see that in the photo. With time, cells called osteoblasts replace that cartilage with bone. As more time passes, the lump shrinks and remodels – hopefully to be not much larger than required to support the bird’s weight. A problem I deal with more in broken wings than broken legs is when important ligaments that allow wing motion become trapped in the new bone callus. It is always a judgement call as to when stabilization devices begin to cause more harm than good. Very frequently check anything that completely circles a leg or wing in any growing animals to be sure it has not become too tight. Another product I use a lot that gives leg support but stretches to allow proper blood to circulation is Tensoplast™. I purchase it in 4″ x 5 yard rolls. Acetone will take residual tape gum off of your scissors. Never apply it on or near animals. The best thing I have found to remove tape residue from feathers and skin is a drop of undiluted Dawn™ dish detergent and your fingernail.

Photo 10 is just another photo I took on the 8th day after the splint was applied. Gently putting fingers above and below the fracture site and gently testing its rigidity, I can see that the device is no longer required. I placed the splint around my little finger, so you could see it better. It was a chore carefully picking off the remaining tags of Tegaderm™ with ophthalmic forceps and tweezers, but the mocker put up with me doing so. I never give anesthetics to immature animals when I don’t have to and when no pain is involved. In adult wildlife aesthetics and/or tranquilizers are necessary to minimize stress and motion. In those cases, I give doses of ketamine &/or diazepam intramuscularly to effect. On rare occasion, I still administer isoflurane gas to bird for general anesthesia. However, placing the required endotracheal tube to deliver the gas into these small bird’s trachea is not without risk, the smell of isoflurane makes me giddy and repeated exposure to iso and similar aesthetic gases is a known risk to your health. When using iso or similar gaseous anesthetics, a dedicated person is required at all times to monitor the bird’s respiration and anesthesia depth.

Photo 11 was taken on day 10. The mockingbird stood its injured foot quite well after I removed the tape and Tegaderm. However, he/she had still not regained the full use of its toes. That has to do with the remodeling bone callus I mentioned to you earlier. This would be a good time to begin some physical therapy. However, mockingbirds and other songbirds resent being restrained and having their feet manipulated. An alternative is to begin providing additional perches that are smaller in diameter and a much larger cage. I always begin my care by give leg-injured birds large diameter branches to perch upon. Besides offering them more foot stability, large diameter branches help keep their toenails from overgrowing during extended periods of recovery. Some injured birds are with me for 6 months before they are finally ready to be released.

I took photos 12 and 13 on the 13th day after the bird arrived. You can see that it has fully regained the use of the toes on its injured leg. Today I put the mockingbird in a large outdoor flight to see how it gets along with the resident mockingbirds that fly free. Mockingbirds are by nature extremely territorial. If they accept it, I’ll just leave the cage door open, so it can come back for food and water when it wants to. We still have several white-wing doves that we raised last summer that occasionally drop by to say hello and eat milo. You can read about how to successfully raise orphaned doves and pigeons here. Two young-of-the-year screech owls come back at sundown for a handout of food as well. Several barn owls we raised do the same. I put a small dab of children’s pink/red nail polish on the tip of a tail feather to keep track of who is who until the next molt. Bands are rarely a good idea. They can easily become too tight or too loose. They disturb balance and they attract predators. The main function of banding birds is often to satisfy amateur scientists or a quest for notoriety.

*************************

Other Options:

Splints are another option when a fracture is partial (“green stick fracture”). Depending on the chick’s age, they can become stable in less than a week. Any device that encircles the leg must be checked several times a day to be sure that it does not restrict blood supply.

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that Google chooses to display on this webpage helps me pay the cost of keeping this article on the Web. As you know, sites like mine that are not designed to make money are getting harder and harder to find. Best wishes, Ron Hines

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that Google chooses to display on this webpage helps me pay the cost of keeping this article on the Web. As you know, sites like mine that are not designed to make money are getting harder and harder to find. Best wishes, Ron Hines