When Your Dog Has Diabetes – Care For Your Diabetic Dog

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Some General Information About Your Dog’s Pancreas

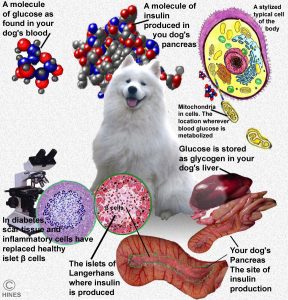

Your dog’s pancreas is a small, light-pinkish organ nestled in the folds of its small intestine. Not much different from yours, it is not a very visually striking organ. An untrained eye might mistake the pancreas for ordinary abdominal fat. You can see it in the fanciful image I drew at the top of this page. Although the pancreas is quite small (about .01% of the body’s weight), it has two very critical functions. The pancreas produces enzymes that allow your dog to digest and absorb food; and it produces a hormone (insulin) that regulates how your dog’s body utilizes and distributes sugar (glucose) in that food. Glucose is the main fuel for all animal cells. Most of that glucose is manufactured in your pet’s liver or liberated from the carbohydrate in its meals. The process by which the pancreas regulates your dog’s blood sugar level is considerably more complicated than my simplified explanation.

Many cell types form your dog’s pancreas. The ones that are important in understanding diabetes are found in small islands (islets) scattered throughout its pancreas (the islets of Langerhans). These particular insulin-secreting cells are called ß (Beta cells). There are two forms of diabetes. The one dogs commonly suffer from is call diabetes mellitus. The much rarer form of diabetes is called diabetes insipidus. Even diabetes mellitus (DM) occurs in two forms. The most common type in dogs is similar in many ways to Type 1 diabetes in humans. There are pitfalls in trying to make the types of diabetes we see in dogs conform to the terminology invented to describe diabetes in humans or in assuming that the causes and treatments for dogs and for us should be the same. For one, dogs were designed to eat meat and have less ability to process dietary carbohydrates – the origin of blood sugar – than us humans do. Some dogs process carbohydrates in their diet better than others. (read here & here) So in some ways, diabetes mellitus in dogs and humans are similar. But in many ways they are not because humans and dogs were designed to eat different diets.

Your dog’s pancreas has a much larger portion – about 95% of the total organ size. That portion’s job is to produce digestive enzymes to digest your dog’s food before it can be absorbed through your pet’s intestines. When that portion becomes inflamed or injured, it often leaks those corrosive digestive enzymes into the tissues surrounding the pancreas. That situation is called pancreatitis. If the islet’s insulin-producing beta cells are injured during generalized pancreatitis, that can leave your dog diabetic as well.

What Changes Occurred When My Dog Developed Diabetes?

The pancreas of healthy, non-diabetic dogs is able to keep blood sugar level between 80-150 mg/dL (4.4-8.3 mmol/L). Periodic, short blood sugar (glucose) rises normally occur after meals (= postprandial blood glucose rise). But for most of the day, your dog’s insulin keeps its blood sugar levels under control.

Your dog’s kidneys are quite efficient in not allowing blood sugar to escape into your pet’s urine. But when the level of glucose in your dog’s blood reaches 180-220 mg/dl, sugar will begin to escape (“spill”) into its urine. So, repeatedly finding your dog’s fasting blood glucose levels in excess or about 150 mg/dl or finding sugar in its urine sample fulfills a diagnosis of diabetes. An alternative to repeated blood glucose urine and blood tests is the glycosylated hemoglobin test which delivers similar information to the A1c test run in humans.

Even though the blood sugar level of diabetic dogs is high, these dogs have problems utilizing that sugar to fuel the cells of their body. That is because insulin is required for the glucose to pass through a cell’s outer wall (the cell membrane). Lacking the sugar energy all cells depend upon, the cells switch to fueling themselves using fatty acids. Those fatty acids do not require insulin to pass through the dog’s cell walls. However, the leftover residues of fatty acids are toxic. These residues can cause a dangerous condition called ketoacidosis.

What Signs Might I See If My Dog Develops Diabetes?

In the majority of dogs the first signs of diabetes that owners notice is drinking more water than usual (polydipsia) and peeing more than usual (polyuria). That alone motivates most dog owners to bring their pets to their veterinarian for a check-up. Others put off bringing their pets to veterinarians until more advanced signs such as weight loss, dehydration, poor hair coat, enlarged tummy (enlarged liver=hepatomegaly), urinary tract infections or cataracts are present. A few arrive already showing the toxic signs of ketoacidosis.

Many pre-diabetic and prediabetic dogs are flagged on their yearly “wellness” blood and urine exams. Those dogs show no serious outward signs of ill health, but their lab results are abnormal. Their blood sugar and triglyceride levels are too high and their ALP, ALT, and AST levels are often mildly elevated as well.

The physical signs that you and your veterinarian might observe are never specific or unique to diabetes alone. Many medical conditions share similar signs. Even the stress and anxiety of a visit to your vet can elevate your dog’s blood glucose levels (and yours). Both fever and kidney disease can also cause increased thirst and urination. A number of non-diabetes related liver and thyroid gland issues can also be responsible for elevated triglycerides, ALP, ALT and AST too. The only way to be sure that your dog is diabetic is to document that its blood glucose level is persistently elevated or that sugar is persistently present in its urine.

How Common Is Diabetes In Dogs?

The incidence of diabetes in dogs is not that high – certainly not as high as heart, kidney or liver disease. It seems to be about one in 500-700 dogs, depending on the study quoted. When it does occur, the signs of diabetes mellitus (DM) usually start between 5 and 12 years of age. It is very uncommon to see it in pets under the age of three. Considerably more female pets (about 72% are female) develop diabetes than males and certain breeds are genetically predisposed to the disease. Those breeds include the Samoyed (the dog in my drawing), schnauzers, keeshond, pulis, poodles, beagles, Tibetan terrier, dachshunds, schnauzers and cairn terrier. Other breeds such as the boxers, golden retrievers and German shepherd dog seem less susceptible.

Just for your general information, when cats develop diabetes mellitus, their situation is more similar to human Type II diabetes than dogs. Those cats still produce some insulin, but it is no longer as effective as it should be (insulin-resistant). So, what needs to be done for cats with diabetes is quite different from the best treatment plans when the disease occurs in dogs. (read here) If you want to read more about diabetic problem in cats, go here. Interesting to me also is that as the frequency of diabetes has risen in people, it has risen in dogs as well as in cats. (read here) The veterinary community in the United States is accustomed to thinking about blood glucose levels in your dog in milligrams per hundred milliliters of blood. The rest of the World is accustomed to thinking about blood glucose levels in millimoles per liter of blood. If you wish to convert one unit of measure to the other, go here.

What Caused My Dog To Develop Diabetes?

Veterinarians cannot tell you with any certainty why your dog developed diabetes. As I mentioned, we know that the disease is more common in some breeds than others. So breed genetics must play a part. We also know that diabetes is considerably more common in dogs that are overweight. We know it occurs more frequently in female dogs – so sexual differences must play a part as well. We also know that medications that favor high blood sugar levels (like corticosteroids) and hormones associated with a recent heat cycle or pregnancy seem to make diabetes more likely. So do adrenal gland issues like Cushing’s disease. Some believe that about 28% of the cases of diabetes in dogs are accompanied by or due to recurrent or chronic pancreatitis. Others believe the number is more likely 40%. I can give you no explanation why, but more cases of diabetes are discovered during the cold winter months. In one study in Wisconsin, diabetes cases in dogs peaks in January and February, (read here) In another report from in England, the same pattern occurred. (read here)

Thoughts On The Causes Of Diabetes In Dogs:

Obesity And Diet

Veterinarians like myself have no information as to how your dog being fat increases its risk of developing diabetes. That’s not surprising; human physicians do not know why being fat increases your chance of becoming diabetic.

In humans, it had long been observed that being overweight increases the risk of Type II diabetes. But Type I diabetes, the type most similar to what our dogs develop, was not traditionally associated with being overweight. Since 2015, opinions on that in human medicine have changed. Physicians now know that fat children are more prone to develop both type II and type I diabetes. Which type they develop, and their underlying susceptibility probably depend on their individual genes. (read here & here)

There are unproven theories on how body weight influences diabetes risk. Most of those theories revolve around the endoplasmic reticulum (=ER), the protein factories that almost all cells contain. In the ER, newly created protein need to be “folded” properly before they can be dispatched to their final destinations. High fat diets and obesity encourage the liver to produce more glucose and release it into the blood stream. High levels of glucose might cause the endoplasmic reticulum enough stress to cause it to miss-fold the newly synthesized proteins. Some believe that that eventually leads to the death of the insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. Of course, that’s just one of many theories. Others theorize that fat releases free fatty acids (NEFAs) that cause pancreatic inflammation and beta cell death.

Although the positive connection between diet ingredients, obesity and diabetes is clearer in humans and cats, it appears to apply to some dogs as well. Fat also reduces the effectiveness of insulin. Compounds called adipokines and leptins are involved in insulin’s effectiveness.

A Link Between Spay/Neuter And Diabetes?

When one removes a dog’s gonads (ovaries or testes), one removes a key player in the animal’s endocrine system. All endocrine glands keep track of what the other endocrine glands are up to. When they sense abnormalities in the system, they attempt to rectify them – sometimes in ways that are not conducive to general good health and well-being. One of the most obvious effects of spay/neuter is weight gain. In dogs and other species, weight gain has been linked to diabetes and chronic pancreatitis. Weight gain has also been linked to a sluggish thyroid gland (hypothyroidism) which has also been linked to the early neutering of male and female dogs. Neutering also increases the risk of hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing’s disease) Cushing’s disease often increases your dog’s blood sugar level. Cushing’s disease also increases your dog’s risk for diabetes. I understand why many of us feel the need to neuter female dogs. The best advice I have for you is to consider personal responsibility as an alternative to surgery, wait for the dog to mature before having this surgery performed and concentrate on keeping your dog lean thereafter. (read here)

Autoantibodies and Autoimmune Disease

Autoantibodies are defensive molecules that your pet’s body mistakenly produces against its own tissue (in the case of diabetes, the dog’s own pancreatic beta cells or the compounds those tissues produce, e.g. proinsulin). There is some evidence that this might be occurring in some diabetic dogs. Similar things occur in humans.

Chronic, Reoccurring Or Sudden Pancreatitis

Some studies report that almost a third of dogs that develop diabetes have chronic pancreatitis. Only a small portion of your dog’s pancreas is devoted to insulin production. The much larger portion produces the enzymes needed to digest food. When that larger portion of the dog’s pancreas becomes inflamed, these highly corrosive enzymes leak into the surrounding tissue. Your pet’s insulin-producing beta cells can be a casualty of that inflammation. Immature keeshonds and golden retrievers occasionally develop sudden (acute) diabetes related to sudden pancreatitis. More recently, a number of greyhounds developed a similar problem. You can read about that problem in greyhounds here.

Your Dog’s Breed And Individual Genetics

It is apparent that certain dog breeds see more diabetes than others and that certain family lines within breeds are even more prone to it. That means that some combination of genes must be at play in promoting the disease. Genes often work in tandem with environmental and other factors that one does have control over. So, the fact that your pet carries increased genetic susceptibility to a disease does not necessarily mean it will develop that disease. There have been great advances in the understanding of dog genetics as it relates to disease susceptibility. A study (limited to one breed) did not find genes that increased some dog’s susceptibility to diabetes; but it did suggest that some gene combinations might protect against it. (read here) A missing “policeman gene” can be just as dangerous as a defecting instructional gene. A more recent study listed breeds in order of their genetic susceptibility to diabetes. Australian terriers, schnauzers and samoyeds top the list. (read here)

Pregnancy and Estrus As Triggers For Diabetes

Your intact female dog’s heat (estrus) cycles have four different stages. The time just before ovulation, when your dog’s vulva begins to swell is proestrus. Once bleeding begins to occur, the dog is in estrus. Fertility occurs in the later part of estrus. After fertility (the time of ovulation) the dog begins a diestrus period of about 60 days. During that period, the increased levels of hormones associated with the heat cycle slowly drop to their baseline levels. Once those baseline lower hormone levels are reached, the dog enters an anestrus period. The length of anestrus is very variable. In larger breeds, it tends to be longer.

Pregnancy increases the risk of diabetes. Usually, the diabetes subsides after pregnancy ends, but occasionally, it doesn’t. We think that the increased risk is due to high levels of progesterone that occur during pregnancy and in non-pregnant dogs for the two months following their heat period (diestrus). Female dogs that develop gestational diabetes tend to be middle-aged and in the latter part of their pregnancy. Certain breeds, including elk hounds and spitz, appear more prone to this problem.

Veterinarians have noticed that the dogs that develop diabetes tend to be older females that are overweight. In spayed female dogs, the disease can develop anytime during the year. In overweight dogs such as elk hounds, it tends to develop soon after they pass through their heat cycles (during diestrus), a time when their blood progesterone levels are high. (read here & here)

Why Does Diabetes Cause My Dog To Drinking And Urinate More?

The simplest answer is that water follows sugar. As your pet’s blood sugar level rises, osmosis draws more body tissue water (interstitial fluid) into its blood. That increases blood volume. As that diluted blood passes through your dog’s kidneys, it enters the many filtering elements (nephrons) that are there. Normally, the nephrons would reabsorb most of that water. But in the presence of elevated sugar, osmosis prevents its re-entry and excessive urine is produced. That lost urine water accounts for your dog’s thirst. Water balance and kidney function are considerable more complex than my simplified explanation.

When dogs have unmanaged diabetes for an extended period of time, they often lose weight. This can occur even when their appetite appears normal or even increased (polyphagia). By the time these pets become underweight, they have usually lost their normal energy level and sleep more as well. They are in a state of malnutrition. They often have elevated blood ketone levels because their body metabolism shifts from metabolizing the glucose that is now no longer available to their cells and draws on its body fats and stored proteins for needed energy. A few ketones are always present, but at high levels (ketoacidosis), they are toxic. Their appetite drops, they may refuse water; they may vomit. As a result, these dogs also become dehydrated. If that is allowed to continue, the dog’s body temperature will become sub-normal, and it will progress to coma.

What Tests And Examinations Will My Veterinarian Perform?

The speed with which each diabetic dog’s health declines is variable. Some eventually develop cataracts in their eyes. At that stage, they often have enlarged livers, abnormal liver enzyme tests. They may have increased susceptibility to infections and delayed wound healing as well. When a pet’s blood is examined early in the disease, the most striking feature is its abnormally high blood sugar (glucose) level. When it is examined late in the disease, many other test parameters are usually abnormal as well. Urine is usually positive for sugar and bladder and kidney infections are not uncommon. Because diabetes in dogs is a disease of middle and old age, other body systems can have health issues that are unrelated to the diabetes. So, it can take your veterinarian some time and a number of tests to sort things out.

After you have explained to your veterinarian the symptoms you have noticed in your dog, your vet will do a complete physical examination. With that background, and particularly with the clues of increased thirst and urination, your vet will almost certainly run some blood tests (a CBC +blood chemistries). A urinalysis that examines a sample of your pet’s urine is essential as well.

Normally, a dog’s blood glucose level is between ~ 80-150 milligrams of glucose per deciliter of blood. (=mg/dL). If you live outside of North America, a normal value would be reported as 4.4-8.3 millimoles per liter (=mmol/L). Your dog’s urine should contain no glucose. In diabetic dogs, blood glucose levels can reach 300+ mg/dl (=hyperglycemia). In those high blood sugar dogs, glucose is usually also present in your pet’s urine (glucosuria). In advanced cases of diabetes in dogs, it is common for your pet’s liver enzymes to be elevated and for blood electrolyte (sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate, phosphate and calcium) imbalances to be present as well. Ketone levels in the pet’s blood and urine are often elevated as well.

Your veterinarian might suggest other tests depending on his/her suspicions. Occasionally, over-active adrenal glands (Cushing’s disease) rather than diabetes are the cause of moderately elevated blood sugar levels. So, your vet might order tests like the urine cortisol/creatinine assay to screen for that. The vet might order tests like the cPL test to detect other pancreatic problems. If your pet’s blood glucose is only moderately above normal, your vet might suggest the fructosamine assay or the glycosylated hemoglobin assay I mentioned earlier that indirectly measure average blood glucose levels over longer periods of time (fright and anxiety at the animal hospital can cause “sugar spikes”). Fructosamine tests are quite helpful in diagnosing marginal cases of diabetes and even more helpful in determining the most effective insulin doses, frequency and treatment plan for your dog. With this test, your veterinarian can tell you how well your pet’s blood glucose level has been controlled over the last few weeks. In locations outside the USA, other tests provide the same information just as well (hemoglobin A1c, glycated hemoglobin, glycated albumin). There are a few rare conditions that can lead to false fructosamine test results. (read here)

Your Dog’s Treatment Plan

The mainstay of your diabetic dog’s treatment plan is providing it with the insulin its pancreas can no longer produce. There are a large number of insulin formulations on the market. None perfectly duplicate the insulin that your dog produces. Among those many formulations, the ones most commonly used by veterinarians to treat dogs are porcine (pig) lente insulin (U-40 porcine insulin zinc suspension, Vetsulin®, Merck Animal Health) and NPH insulin (isophane insulin, Humulin I® 100 IU/ml). Vetsulin is a resurrection of an old Lilly Pharmaceutical product, LENTE®/ ILETIN® II. Veterinarians became comfortable using lente in dogs and cats until recombinant insulins like Humulin® replaced its use in people.

One study found that both are almost equally effective in dogs. (read here) Until the publication of that article, most veterinarians believed that NPH insulin has a shorter period of effect in dogs. But choosing one or the other product for your dog is the easy part. Determining the best dose size and the best injection interval for your dog is the extremely difficult part.

A diagnosis of diabetes in your dog insures that you and your veterinarian must form a close working relationship. It will not be easy; it will be stressful. It will require a close and amicable relationship with a veterinarian you trust – perhaps not the one that initially discovered the problem, perhaps not the one most conveniently located to your home. For your happiness, satisfaction and success, spend a lot of thought choosing a veterinarian who is a good fit for you and your dog. Diabetes will be a lifelong challenge for your dog and for you. To be successful in dealing with it, you must find a team whom you trust and whose personal philosophies and practice styles matches yours. Not all veterinarians and staff are good communicators and no veterinarian pleases every single pet owner. It is just not possible due to the nature of the services we deliver. Some practices are too rushed or pass patients between multiple practitioners. If you don’t feel entirely comfortable with your veterinarian and the office staff, look for another. The best way is usually to ask your friends and pet care professionals whom they recommend. Join support groups. There are plenty of wonderful, supportive veterinarians out there – but you have to search for them.

Additional things, like daily exercise, diet modification and weight loss for chubby dogs are important too. But managing your dog’s blood sugar level with insulin is the critical factor. In doing so, you will try to keep its blood glucose level as close to normal as possible without ever dropping to dangerously low levels (hypoglycemia).

Don’t assume that because your dog appears stable, that it does not need continuing veterinary checkups. In my opinion, the most important test to monitor your diabetic dog’s status over time is the blood fructosamine assay performed 3 – 4 times a year in dogs that appear well regulated based on their glucometer readings – and more frequently if they don’t. If you can’t afford all these tests, you will need to learn to be proficient in the use of your dog’s glucometer and keep good records.

Will Treating My Dog Take A Lot Of Time And Commitment On My Part?

Yes.

Not every dog owner can, or wants to take on this responsibility. Yet, many owners derive great satisfaction and personal growth from the experience. Dog owners may find that caring for their diabetic pet produces an intense bond and personal satisfaction that they had never until then experienced. The decision needs to be a family decision because it will affect every member of your family, your spouse, your children, your co-workers, your other pets. Not only will you have to decide if you will treat your dog, you will have to decide on the level of treatment. These are things that veterinarians are not taught in school to help you with. Some intuitively understand it; others do not. The most worrisome factors for some owners are the difficulty of finding pet-sitters and boarding facilities when you travel, some loss of control in your life due to the added responsibility, more difficult interacting with family and friends, more worry, less time for social life, added costs and interference with your work life. The same issues are faced by owners of diabetic cats. Probably the least important fact for you to worry about is your ability to perform the procedures that will be involved. None of these procedures are that difficult to master and there are plenty of dog owners and veterinary staff willing to instruct you. If you live in an isolated area, the Internet is full of instructional videos. Try not to be motivated by guilty feeling that you were in some way responsible for your pet’s diabetes.

As Important As The Type Of Insulin You Give, Is How You Give It

The biggest pitfall in administering insulin is inadvertently giving too much, due to distractions, a new formula or bottle size, or an incorrect syringe size. Your veterinarian or his/her technician will demonstrate how and where the injections should be given. Don’t attempt to use syringes designed for one insulin product with a different insulin product until you are absolutely certain the gradations (numbers) on the syringes are accurate for the insulin product you were given. If you are in doubt, have a pharmacist (not a busy pharmacy technician) confirm that the syringe and the insulin product are compatible. Some communities regulate how used syringes can be disposed of. If this is a potential problem, call your local sanitation department and ask what is allowed in your area.

How To Give Your Dog Its Insulin Injection:

Insulin injections are always given under the skin (subcutaneously). On either side of your pet’s spine, is a convenient location. Alternate the sides and exact locations to minimize pain.

1) Feed your dog. Meanwhile, let the insulin bottle warm up to room temperature.

2) Swirl the bottle around to be sure it is well mixed. Don’t shake the bottle violently.

3) Withdraw the insulin into the syringe to the proper gradation, being careful not to draw in air bubbles. If bubbles appear – gently force the product back into the bottle and try again or tap the syringe with your finger until the bubble rises high enough to be expelled.You may have been holding the bottle at the wrong level or the product may be foamy from excessive agitation.

4) Place the syringe on a clean surface and call your dog.

5) Lift a fold of skin along the dog’s back. Insert the needle almost parallel to the surface of the back but angular enough to be certain you are under the skin and not in it.

If you are in the skin, rather than under it, there will be resistance in the syringe when you inject and your pet will feel pain.

Part your dog’s fur to be sure the needle has actually penetrated under the dog’s skin. There is no reason you cannot clip the hair to make this an easier and more hygienic process.

If you give the injection properly, the dog will probably not fuss or even be aware that the injection was given. Skin sensation varies according to breed. Hunting and fighting breeds of dogs have considerably less reaction to injections than terriers and toy breeds.

Reward your dog with love and praise.

Insulin Injection Pens

Some dog owners find preloaded insulin pens that deliver a rapid, measured amount of insulin more convenient. It is a more expensive option than syringe and needle, but for owners or pets that dislike injections for one reason or another, it is a convenient option. The pens are not very accurate with the very small doses required by very small pets. Talk to your veterinarian to see if this is an option for you and your pet. I still prefer needles and syringes; I feel that I have more control in placing the injected liquid under the skin and not into the muscle. Intramuscular injections of insulin cause too rapid a drop in blood glucose with a shorter period of effect.

What If The Calculated Dose Of Insulin Does Not Lower My Pet’s Blood Glucose Level Enough?

Blood sugar level in some pets is harder to control than others. Some call this “insulin resistance”. But that is a confusing term because true “cellular insulin resistance” is a phenomenon that occurs in human Type II diabetes – not the form of diabetes common in dogs. The first thing to do is to be sure you are really giving the amount of insulin suggested by your veterinarian. The biggest cause of unexpected or poor results is giving the insulin product incorrectly. Be sure your bottle of insulin is not expired and that it has been properly stored (most formulations must not be frozen). The next thing to do is to verify that your glucometer is accurate and that you are making your glucose level determinations correctly. The best way to do this is to check your dog’s blood sugar level on two different meters. Blood glucose levels are constantly changing. You will need to do the two tests simultaneously or one right after the other. If neither of the above problems are occurring, your veterinarian will probably increase or lower your dog’s insulin dose. Generally, veterinarians begin pets on a low or moderate dose of insulin. That leaves room to adjust the dose upward if need be. If changing your dog’s insulin dose still does not solve the problem, your veterinarian may try your pet on another brand or formulation of insulin. Trying alternative subcutaneous injection sites; have another experienced person administer the injection to see if the results are the same; and changing the hour of the injection(s) and feeding schedule sometimes also solves the problem.

Here are other factors that sometimes cause this problem:

Overly plump dogs and dogs eating high fat, greasy diets sometimes have problems utilizing injectable insulin. (read here) Some dogs are known to produce antibodies against certain insulin formulations that prevent their proper action. This seems to be a particular problem when cow pancreas, rather than pig pancreas, was the source of the insulin. (read here) Pets that are receiving corticosteroids for other health problems may appear to be more resistant to the benefits of their insulin injections. This is because corticosteroids raise blood glucose levels. Corticosteroid levels are also elevated in Cushing’s disease (hyperadrenocorticism). Your vet may screen your pet for this condition when insulin appears less effective than it should be in lowering your pet’s blood glucose level. As I mentioned earlier, If your pet is a non-spayed female, high progesterone levels that accompany and follow her heat periods can affect her blood glucose level and can make insulin doses less effective.

Hypothyroidism, urinary tract infections and acute pancreatitis attacks can also make dogs more resistant to the insulin you inject. (read here)

Somogyi Overswing

Occasionally, what appears to be an ineffective insulin dose is really due to receiving too large a dose of insulin. This is called rebound hyperglycemia (somogyi Overswing effect). When it occurs, the dog’s blood sugar level drops drastically and rapidly after receiving too large a dose of insulin. But the dog’s body quickly releases its own cortisol and adrenaline that cause its blood sugar to soon rise to abnormally high levels again. Careful examination of your pet’s blood glucose curve will detect this phenomenon. The treatment is smaller and possibly more frequent insulin doses.

Checking Your Dog’s Blood Glucose Level At Home

Keeping a close watch on your pet’s blood sugar level at home is the key to keeping it healthy. The best way to do this is for you to purchase and learn to use a hand held glucometer. Obtain the small blood samples by pricking its skin with commercial lancets. You will find, through experience, which sites bother your pet the least. Your pet’s upper and lower lips, (near the base of the jaw) generally works well. So do the calluses to the side and rear of their elbows and their metacarpal foot pads (the one on the rear of the front leg that does not touch the ground) The base of the tail works well, if you first shave the area. Generally, the least painful areas are contact points with the floor when your dog is at rest. Although many owners prick their dog’s ears, I find them more sensitive than these other locations. Most dogs accept this procedure readily. Those that won’t will have to rely on periodic glucose testing at their veterinarian’s office, the services of a house-call veterinarian or periodic blood fructosamine tests. Checking for the presence of glucose in your pet’s urine is not sufficient. Sugar does not enter your pet’s urine until its blood sugar level is quite high, and it may only appear intermittently. But I suppose urine test strip testing is a better test than no testing at all.

Your Glucometer

At one time, more dog owners used human glucometers to test their pet’s blood sugar levels than the meters designed specifically for dogs and cats. That was primarily due to the difference in their cost. What should concern you more than the price of the unit is the price of the test strips. Over time, the strips represent most of your true cost. Cheap strips are also often short-dated.

The problem with using a glucometer designed for humans on a dog or a cat is that blood glucose is distributed differently in the blood of humans versus the blood of dogs and cats. In humans, about 58% of the glucose is free in the blood plasma and 42% is tied up in the red blood cells. In dogs, it has been reported that 87.5% of the glucose is free in the plasma and only 12.5% is tied up in the red blood cells (cats 93% in plasma, 7% in the red blood cells). The way human glucometers are calibrated at the factory, that means that they will likely read a lower blood sugar level than actually exists in your dog. I suggest you purchase a glucometer designed for dog and cat use – although formulas exist that allow approximate conversion of human meter readings into dog and cat readings.

No matter what brand you buy, check your unit and your strips periodically against the one used by your veterinarian as well against your test solutions. Remember that blood serum and plasma glucose levels run at a lab are often 10-15% higher than results obtained on meters. The most important attributes to look for in a meter are accuracy and repeatability of results. A very small amount of required blood sample – particularly if your dog is small is also important. Another important meter feature is that its test strips be very absorbent in drawing up blood from your test prick site (“sipping”). Unless you are uploading your dog’s results to a graph on your computer, additional features, that are added to many meters, are really an unnecessary complication and expense.

Be aware that meters marketed to the US give their glucose reading in milligrams/deciliter (mg/dL). In the rest of the World, the meters usually display in millimoles/liter (mmol/L). There are websites that will do automatic conversions.

Factors That Can Affect Your Meter Reading

Anemic pets may appear to have higher blood glucose levels than they really have. If your dog is not consuming enough water or if it is dehydrated, it may also test higher. Testing after your pet eats a fatty meal can also influence the meter reading as can vitamin C supplements. Other things that commonly cause inaccurate readings are low batteries, expired test strips, insufficient or too much blood on the strip, dirty meters and failure to regularly check your meter’s calibration against the test solutions.

Preparing A Glucose Curve Chart For Your Dog

Persistently high glucose levels damage your dog’s health over time. Occasional spikes are not that important, what is important is that your treatment plan keeps glucose at as close to normal as possible over the majority of time.

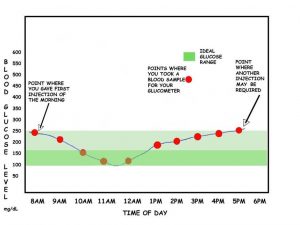

Plotting the curve will let you do that. It is the only intelligent way to adjust your pet’s insulin dosage. It will tell you the highest and lowest blood glucose reading of the day, how long it takes the injection to affect your dog and the length of time the insulin remains effective. You will use the graph results to adjust your pet’s not only to adjust its dose, but also to choose the best insulin type for your pet, the best injection interval, best diet, exercise plan and lifestyle in a way that keeps its blood glucose level as stable and close to normal as possible with the fewest dramatic peaks and valleys (nadirs). That was the job of your dog’s pancreas. It is your job now.

Recommendations vary as to how to prepare glucose curve charts. I prefer clients prepare their curve at home where their dog is relaxed, not at an animal hospital. I tell clients to obtain their first glucose reading one hour prior to their dog’s morning insulin injection, one hour after the injection and then every hour until the reading has reached its lowest point and begun to rise again. From then on, the sampling can be done every two hours.

You should always allow your pet to become accustomed to a particular insulin dose and treatment plan for a few days before attempting to prepare a full glucose curve. You should also be aware that the test has limitations – it is hard to get reproducible curves on consecutive days, and that there is considerable day-to-day variability. Sometimes the curve you obtain will not mesh with your dog’s clinical picture. Occasionally, the curve may show that your pet’s glucose is under good control when it isn’t. If your dog is continuing to drink and urinate excessively, experiences periods of weakness, or fails to normalize its weight, go with your intuition that something is wrong and call your veterinarian. I prepare graphs similar to the one in my illustration using Graph 4.3. You can also use the online Vetsulin® insulin curve generator if the link still works.

Adjusting Your Dog’s Insulin Dose Based On Its Insulin Curve

For these graphs to be accurate, they are best prepared at home. At an animal hospital, your pet’s eating habits, ability to exercise and stress level will be quite different from at home. That will often affect the results. There is no one firm rule as to what your dog’s “normal” blood sugar level should be because it is constantly fluctuating. But a value that I often used is about 75 – 175 mg/dL (4.2-9.7 mmol/L), with the average being around 80 mg/dL (4.4 mmol/L). Don’t attempt to maintain your dog at or below 100 mg/dL. That would leave too little down space between what is normal and what might lead to hypoglycemic shock. Instead, consider an 100 mg/dL – 185 mg/dL (5.5-10.3 mmol/L) average or so as your ideal goal. Some owners of easy-to-regulate pets succeed in keeping their average blood sugar level lower. But it is not something you should attempt until you are thoroughly comfortable with how your pet responds to its injections. Do not become frustrated if you cannot maintain an ideal blood glucose level in your pet. Many owners must be content with higher peak levels. If your dog’s blood sugar reading reach peaks over 180 – 270 mg/dL (10-15 mmol/L), sugar will begin to appear in its urine. Dogs with persistent readings over 250 mg/dL (16.6 mmol/L) are at risk of developing health complications. These pets often have ketone-positive urine. When contemplating your pet’s insulin curve, look for trends – not specific points.

BE VERY CAUTIOUS WHEN YOU ATTEMPT TO CHANGE YOUR DOG’S INSULIN DOSE. ALWAYS DO SO IN CONSULTATION WITH YOUR VETERINARIAN. GIVE NON-HYPOGLYCEMIC DOGS AT LEAST FOUR DAYS BEFORE DECIDING THE TRUE EFFECT OF THE CHANGE AND BEFORE ATTEMPTING ANOTHER CHANGE.

Many pet owners follow the ten percent rule – never changing their dog’s insulin dose by more than 10% in 4 days. Every pet is different. A few require more than the typical twice-a-day injection procedure. Insulin dose and frequency adjustment is more of an art than a science. There is quite a bit of variation in blood glucose from day to day in the same pet. That is why there is so little agreement on exact figures and procedures. I am confident that many seasoned owners of diabetic dogs have discovered schedules and procedures different from mine that work great for them. If you are new to diabetes care, you can be overwhelmed by these conflicting opinions. At some point, you will just have to choose a protocol that appears reasonable to you and is offered by a person you trust.

There is one other thing I do not want you to do.

I do not want you to base the treatment of your diabetic pet on this article. You need a hands-on veterinarian coaching you, not a provider of Internet advice like myself, or information you read on some blogsite. Online veterinary advice can be an important aid to you, but it is not a substitute for your local veterinarian. Repeat your curves every 3-6 months – more frequently if you are having glucose control issues. Most veterinarians believe that that the flatter your pet’s glucose curve remains – with the least dramatic peaks and valleys – the less likely it is that diabetes-related health problems will occur in your dog.

Are There Drugs Other Than Insulin That Might Help?

Some veterinarians believe that oral metformin can be helpful in minimizing peaks and valleys between your dog’s insulin doses. (read here)

What If My Dog Is Not Eating?

When your pet is not eating, its insulin needs are lower. It is also more likely that its blood sugar level will drop to dangerously low levels if you give it its usual insulin dose. Sometimes, fairly minor things like excitement, stress, indigestion or human family emergencies prevent your pet from eating on schedule. In those instances, be cautious and give your pet less insulin than you normally do. Then observe it. Remember, a day of high blood sugar is not nearly as serious as an hour of dangerously low blood sugar.

Is Dietary Therapy In Addition To Insulin Important?

Most veterinarians think it is.

In Type II diabetes, the common form in humans, we know that feeding diets with added fiber, reduced fat and complex carbohydrates substituted for simple sugar are all helpful in regulating blood glucose levels. Less information exits regarding dogs. But we do know that fatty diets, in addition to making your pet obese, reduce your dog’s ability to utilize insulin (read here) and it did initially appear that canine diets with added insoluble fiber (sugar beet pulp) help stabilize blood glucose levels in dogs. (read here, here & here) But a more recent study did not find any advantages in feeding high-fiber, reduced carbohydrate diets to diabetic dogs and warned against their use in dogs with thin body condition. (read here) Two studies found that low carbohydrate, high protein, moderate fat content appeared to improve how dogs handled blood sugar. (read here & here)

Despite all the hype from prescription dog food manufacturers, that is all the legitimate science we have to back up their claims. You know how many people tell you what you should, or should not eat. It is no different with our pets. Basing diet formulations on a compound (glucose) that bounces up and down due to multiple factors and doing it in only a few purpose-bred beagle dogs for short periods does not yield much practical information.

Here are some suggestions:

1) If your dog is overweight, limit its total caloric intake and optimize its weight. Crash diets are never appropriate. Just gradually reduce the total amount of food calories your pet consumes in a day. Adding high fiber ingredients to your pet’s diet will allow you to do that without your pet being hungry all the time.

2) Do not feed food ingredients or dog foods that are greasy or high in fat. Most dry dog foods have fat sprayed on the baked kibble after heat extrusion. Dogs naturally like grease, so this process makes the food more palatable and allows the inclusion of ingredients that dogs would not readily accept. An added problem is that this grease is often rancid. Rancid (oxidized) fat contributes to oxidative stress on the body. (read here, here & here)

3) Feed a diet low in simple sugars. You can substitute complex carbohydrates if you include them at all. There is no evidence that dogs need carbohydrates. Most commercial brands add them because they are cheap.

4)Feed your dog at very regular, consistent intervals, preferably soon after its insulin injections. Avoid caloric snacks as much as possible. When you do give treats, find low-cal treats your dog enjoys.

5) Do not feed low cost, low-quality or generic dog foods. See to it that the bags are not old or stale or improperly stored.

6)Do not feed your pet semi-moist, embalmed, dog food or treats. Many are preserved with propylene glycol, dextrose, fructose or glycerin – all ingredients diabetic dogs should avoid.

7) Feed many small meals throughout the day.

I usually suggest that clients feed their dogs a, nutritionally balanced, homemade diet whenever possible. But I understand that not all of us have that option or inclination. You can find some homemade diet suggestions here. Us humans do not usually rely on professional nutritionists to plan our meals, but if you are hesitant about the homemade foods you feed your dog, there are veterinary nutritionist associated with veterinary schools who can review your plan. You must be cautious when feeding high fiber commercial or homemade diets to diabetic dogs that are underweight or experiencing health problems that affect their ability to metabolize food. Determine what the optimal weight for your pet is and weigh it frequently to be sure it is not becoming underweight. Pay attention to the luster of its coat, flakiness of its skin and general energy level when on these diets. Some dogs do not like the taste or smell of commercial diets marketed for diabetic dogs. Try various brands. Never give ultimatums or force your dog to eat these diets. Try introducing them to the new foods very gradually. If they refuse to eat it, and they are currently on a nutritionally balanced, sensible diet, proper insulin administration and exercise will allow you to manage their diabetes problem quite will without it.

Regular Exercise Contributes To Success

Always begin exercise programs cautiously and slowly. Keep in mind that you are unlikely to lower your pet’s weight through exercise alone. You will need to control what the dog eats and how much it eats as well. But exercise will certainly help to achieve its ideal weight and exercise has great health benefits beyond weight reduction alone.

Simply reducing the food intake of plump dogs will cause them to be more active, alert and exploratory. Exercise also changes the way cells react to insulin. (read here) And, although not as great a risk factor as it is in humans or cats, studies have found that indoor confinement and inactivity are major risk factors in developing diabetes. Exercise can lower your pet’s blood glucose even without the action of insulin.

What Are Some Danger Signs I Need To Watch Out For In My Pet?

Diabetic pets have an increased risk for certain problems. If you know what these problems are, you are more likely to discover them early, when treatment is more successful. I listed them roughly in the order of their importance and frequency.

Hypoglycemia – Abnormally Low Blood Sugar

Blood sugar levels drop to dangerously low levels in diabetic dogs when you give them too much insulin (less than 55 mg/dL). That can be because their dose was too large or because it was more than their current needs. Perhaps they did not eat that morning, exercised more than usual or were under unusual stress. The earliest signs of this problem that you will see are restlessness, trembling or shivering, loss of coordination and behavioral changes. In mild cases, they may just become unusually hungry. If their blood sugar level continues to drop, pets become sleepy, unresponsive and eventually lose consciousness. The speed with which this all occurs is unpredictable. If your dog is still willing to eat, immediately offer it some of its normal diet. Check its blood glucose level with your glucometer. If its blood sugar reading is abnormally low, try to make a list of things in your mind that may have caused the problem and avoid them in the future. Call your veterinarian to discuss the problem and see if your dog needs to come in. If the problem appears serious, just put your pet in your car and take it in immediately.

Not all hypoglycemic dogs are capable of eating food. Never attempt to make a seizuring or confused pet swallow food or anything else. They might choke. To deal with hypoglycemic pets that cannot eat, owners should have a liquid glucose (dextrose) source readily available in their home. One half gram (500 mg) of glucose per pound body weight is often suggested. One level tablespoon equals about 14 grams of finely powdered glucose, 50% dextrose solution contains 500 mg/ml.

You can ask your veterinarian for a syringe or container of 50% Dextrose (5% dextrose, D5W is too dilute). I make sure all my clients have some around – particularly when they are just beginning or changing insulin doses. You can also go to your pharmacy or Walt-Mart, purchase some glucose tablets (Dextrosol®, B-D glucose tabs™, etc.) and dissolve them in warm water. Wait 15 minutes, then check your pet’s blood sugar level again. Repeat the dose if need be. Keep unused sugar solutions refrigerated.

Some folks suggest Karo Syrup or anything sweet. That is better than nothing, but not as effective. Products containing table sugar contain sucrose, not glucose (aka dextrose). Sucrose is 50% glucose and 50% fructose. Karo Syrup is a form of high fructose corn syrup. It contains more glucose than generic corn syrups, but it also contains other sugars. Generic Corn syrup is 55% fructose and 42% glucose. Although your dog’s liver can metabolize the fructose into glucose, that takes more time (intermediate glycolysis in its liver).

The best way to give glucose solution to your pet is by wetting the lining of its lips, mouth and tongue with it. Some suggest smearing it under the tongue. Just be careful not to be bitten or use a toothbrush to “paint” it around the oral surface – dogs that are “spacey” from hypoglycemia do not know what they are doing and their jaw muscles often spasm. Do not pour or squirt liquid into the dog’s mouth – it is liable to go down wrong. Small, periodic amounts of glucose are better than one large amount. Some folks say it can also be given through the other end with a rectal enema. Theoretically, that is possible. I have never tried it. I would prefer you just get a pet in that debilitated a condition to a veterinarian as rapidly as possible.

Many owners are hesitant about giving glucose to their pet – after all, they were under the impression that the whole point of diabetes treatment is to lower glucose sugar. Don’t worry about that in a hypoglycemic emergency. The short period of time your dog’s blood sugar level will be high will have no effect on its long-term health. As soon as your pet is willing to eat, allow it to. Keep a close watch on it, that the problem does not return – the glucose you gave will have only a short time effect (sugar high) and may need to be repeated. As soon as it can eat its normal diet, it will get the more complex carbohydrates that supply sugar in a more steady stream. After the incident has passed, sit down with your veterinarian to re-evaluate your pet’s insulin dose, interval and any other factors that might have caused this crisis and correct them. Remember that the glucose curve graph you made for your dog may not have caught blood glucose at its lowest point between blood-draws. If the curve was headed in a downward slope, it may have dipped even lower sometime before the next time you drew blood. That may have been the point when hypoglycemia occurred.

Ketoacidosis – What Are Ketones, And Why Are They So Important To Avoid?

When your pet lacks insulin and can no longer fuel its body’s cells with blood sugar, it switches its metabolism to fuel those cells with the fatty acid portion of its stored body fat and portions of its own muscle protein. This metabolic switchover leads to excess formation of ketone (ketone bodies). Some are always forming in your dog’s body. But when the process accelerates in pets starved for energy due to diabetes, or fasting from a lack of food or appetite, the excess ketone acidifies its blood to dangerous levels. This condition is called ketoacidosis (aka DKA or ketosis). Signs of ketoacidosis can include, vomiting, diarrhea, weakness, dehydration and rapid shallow breathing. The body can only operate in a narrow range of acidity (pH). Blood glucose levels in these cats are usually sky-high and ketones are present in the urine. Untreated, severe ketoacidosis can be rapidly fatal. (read here & here) When uncontrolled (unregulated) diabetic dogs are presented to veterinarians in this condition, they require immediate IV fluid administration to correct dehydration, rapidly acting, short-term insulin to bring high blood sugar levels down, often additional intravenous potassium, continuous monitoring and intensive care. Some pets become deficient in blood phosphorus as well and many require intravenous buffers (bicarbonate) to bring their blood pH back into normal range. Many of these dogs have other health problems (like Cushing’s Disease) that make the problem worse. It is not unusual for veterinarians to make their first acquaintance with a diabetic client during a ketoacidosis crisis. That is the first occasion that some pet owners realize that something is seriously wrong with their dog. You can monitor your pet’s ketone levels at home. The procedure is simple. It only requires urine dipsticks (Ketostix™) available online or at the pharmacy with no prescription. Check your pet’s first urine of the morning. Do not panic if it is occasionally weakly positive. If it remains so for two or more days in a row, consult your veterinarian. Portable meters are also available to do this if your pet suffers recurrent attacks. (read here)

Eye Problems Sometimes Associated With Diabetes – Cataracts

Dogs that develop diabetes are more prone to develop cataracts in their eye lenses as well. When a cataract problem is advanced, your pet may be unable to see. Cataracts are lenses that are no longer clear to the passage of light. There are many kinds of cataracts that affect dogs, the most common form, affecting all old dogs, is not a true cataract at all, and it is not related to diabetes. In those old dogs, the fibers that compose the lens become tighter and more densely compressed together, reflecting a hazy cloudiness. This is referred to as lenticular (nuclear) sclerosis. Although lenticular sclerosis may look serious to you, the dog actually retains most or all of its vision and will not bump into objects or walk hesitantly. Read more about cataracts in dogs here.

When true cataracts such as diabetic cataracts occur, the dog’s lenses appear mottled or appear to be fractured like a broken chunk of ice. True cataracts can occur in one or both eyes. But the normal nuclear sclerosis of aging occurs simultaneously in both eyes to the same degree. When true cataracts form in diabetic dogs, they form because of increased glucose levels in the eye. Your pet’s lenses are alive. Like all living tissue, they need nutrients. In their case, the nutrient is glucose. However, when glucose levels are too high, some is converted into another sugar, sorbitol, that has destructive consequences for the dog’s lens.

Remember that even if your diabetic dog should lose its vision, it will remain a happy and contented soul. That is because dogs interact with the people they love and their environment much more by scent than by vision (their sense of smell is many more times more sensitive than ours)

There are veterinary ophthalmologists who can remove one or both of these cloudy lens and replace them with artificial ones. But that is not a surgery that I often recommend. Complications are frequent. it is expensive, and it subjects your pet to a lot of unnecessary stress. I do suggest that pets with diabetic cataracts be seen by a veterinary ophthalmologist occasionally to confirm that pressure within your dog’s eyes remains normal and is not elevated and that no inflammatory eye changes (uveitis) is present. Eyes that have cataracts are more subject to those sorts of problems (read here) as well as to “dry eye” (keratoconjunctivitis sicca). (read here) Although diabetic cataracts do not generally improve on their own, there have been reports of it happening in dogs. (read here) There are also medications that might slow the cataract formation process. (read here) Humans with diabetes are more susceptible to various other eye and vision problems. We do not know if dogs are too.

Diabetic Dehydration

(aka: Severe Hyperglycemia, Hyperosmolar Non-ketotic syndrome, HHNK, HHS)

When a dog’s blood sugar level falls below 60 mg/dL it will show the signs of hypoglycemia. However, on rare occasions the blood sugar levels in untreated or inadequately treated dogs will soar to extremely high levels – greater than 650 mg/dL. In such an extreme hyperglycemic state several things are likely to occur:

The blood of a dog with this elevated amount of sugar in it has an extreme affinity for water. So water is sucked out of the brain and other organs and into its bloodstream. This results in severe depression and weakness. If your pet stops drinking and eating and can rapidly become comatose. Water is not only lost from the brain, it is lost from the body through high-sugar-content urine. So, the dog becomes severely dehydrated as the amount of fluid in its body drops and the dog is too weak and disoriented to drink (hypovolemic shock). These dog’s eyes become sunken, and their gums are usually tacky or dry. Their skin looses its normal spring-back elasticity and remains “tented” when it is finger-plucked upward. This results in dehydration at the intracellular level too – fluids are literally sucked out of the body’s cells by the extremely high level of blood glucose. This is not ketosis, so your pet’s urine remains relatively ketone-free. In these emergency situation, dogs need to receive large amounts of intravenous fluids in an attempt to rehydrate their brain and bodies. They usually need replacement potassium and phosphate as well. Despite aggressive therapy the recovery rate from this situation is quite low.

High Blood Pressure

Diabetic dogs are at increased risk of developing elevated blood pressure (hypertension). (read here) High blood pressure can cause kidney damage in dogs. So, it is wise for your vet’s periodic health checks to include a check of the dog’s systolic blood pressure. Should it be high, there are medications to help lower it. Should it be high, a check of your dog’s kidney function (blood creatinine) might be a wise decision as well.

Nerve Problems Associated With Diabetes

Nerve problems do not seem to occur as frequently in diabetic dogs as they do in diabetic people. But they have been reported. (read here) The most common reported sign is rear leg weakness. There are many non-diabetic explanations for rear leg weakness in older dogs – the most common being spine and spinal disc issues unrelated to diabetes. When things remain unclear, nerve conduction studies might be able to sort the problems out. (read here) There is also some evidence that uncontrolled diabetes can affect the nerves that control heart rhythm (vagal neuropathy). (read here)

Be Cautious When Giving Your Diabetic Pet Other Medicines

Certain medications, particularly corticosteroids, interfere with the positive actions of insulin. Diabetes can also alter the way your dog handles other drugs. The major organs where insulin is active are the liver, muscle and fat tissue. So, any medications that affect those organs have the potential to affect diabetes control. Diuretics (thiazide diuretics), thyroid hormone supplements, anabolic steroids, niacin, melatonin, certain antibiotics (e.g. tetracyclines, erythromycin), certain heart medications (beta blockers) and aspirin (unsuitable for dogs or cats), among others, may have the potential to affect the glucose dynamics of diabetic dogs. General anesthesia in dogs is affected when your pet is diabetic. (read here)

If My Female Dog Is Not Neutered Will Neutering Help In Her Treatment?

If an unneutered female dog’s blood sugar is periodically hard to control, spaying her may help. Don’t rush out to spay your elderly dog just because it has developed diabetes. Wait to see how well standard insulin, diet, weight loss and exercise control her blood glucose level. Progesterone, a hormone of periodic heat cycles and pregnancy, interferes with glucose control. It is present in substantial amounts from the middle of your dog’s heat period and for about two months thereafter – regardless whether the dog gets pregnant. If you have difficulty controlling your dog’s blood sugar level during that time, spaying her might help. If diabetes began or is difficult to control in another portion of her heat cycle, I doubt that spaying her will help.

Gestational Diabetes

A few female dogs have the potential to develop diabetes during their pregnancies. Increased thirst and urination occurs, similarly to what sometimes occurs in eclampsia. Gestational diabetic dogs are more likely to have urine accidents in the house. An elevated fasting blood glucose level is diagnostic. Your dog’s blood glucose level should return to normal once the puppies are delivered.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.