The History Of Dog And Cat Food – What’s In The Cans And Sacs And How It Got There

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Back to parent article on Raw Diets

Back to parent article on Raw Diets

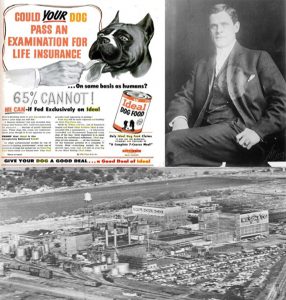

This enterprising Canadian gentleman above is Thomas Wilson. In 1916, he took control of the third largest slaughterhouse in Chicago, Armour and Swift being the 1st and 2nd. The photo is a 1961 view of his Oklahoma City meat packing plant and offal refinery.

During the slaughter and processing of meat, these companies produced an enormous amount of byproduct. Only 60-65% of a cow is edible meat. Much of the rest was processed into shortening, lard, industrial greases, soap, candle tallow, gelatin, glue, hairbrushes, buttons and fertilizer.

But those other uses could not keep up with the vast amounts of waste these Companies generated. So, Wilson and his competitors found other novel outlets – animal intestines were used to make surgical suture and violin strings. By 1914, Wilson had established a sporting goods subsidiary to market tennis rackets – strung with the dried and processed cow entrails (intestines) he had so much of. That affiliated company eventually evolved into the Wilson Sporting Goods Company that you know of today.

By the 1920s, these three companies saw the emerging pet food industry as likely being a profitable way to market their excess material. Armor began to market a canned meat product called Dash™, Swift produced a similar one called Pard™ and Wilson marketed his as Ideal™ “The 7-Course Meal In A Can”. By 1941, those and similar pet foods in tin-plated steel cans accounted for 91% of the American pet food market.

What ended that all was World War II. In April of 1942, the US War Production Board ordered a reduction in the non-strategic use of tin and steel (tin was in short supply because Japan controlled 70% of the World’s tin resources). So, during the War years, canned dog and cat food disappeared from American grocery shelves. In its place, a baked, dry, paper-packaged product produced by Clarence Gaines (Gaines Dog Meal) replaced it. By 1946, baked dry foods like his had captured 85% of the market. Tin cans came back after the war; but the public had found the convenience of dry pet food too hard to give up.

The Golden Age of dry dog and cat kibble began in 1957 when Ralston Purina Company introduced the first hot-extruded pet kibble (Purina Dog Chow). Because the Danforth family’s prior feed manufacturing experience was in producing high-carbohydrate, grain-based poultry and livestock rations; they naturally continued formulating and manufacturing dog and cat chow the same way on the same machines. During WWI, William Danforth noticed that the word chow “raised our soldier’s spirits” so he included the word “Chow” in all his Purina brands.

That long journey through history is another reason why there is so much carbohydrate and byproducts in the dry “chows” your dog and cat eats today.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.