All About Your Parrot’s Feathers

The Causes of Molt, Feather Problems And What You Can Do About Them

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Is This A Wild Bird? If So, This Links To All Of Dr. Hines’ Wildlife Care Articles

Is This A Wild Bird? If So, This Links To All Of Dr. Hines’ Wildlife Care Articles

To learn more about why some parrots pull out their own feathers, go here

To learn more about why some parrots pull out their own feathers, go here

To learn more about parrot nutrition go here

To learn more about parrot nutrition go here

Feathers are a bird’s most precious possession – beautiful and complex structures that give the gift of flight and insulate their bodies. However, after about a year, these delicate structures wear out. Even with careful preening, the feathers get frazzled and crimped from the wear and tear of ordinary activity.

In this article, I put detailed stuff that most bird owners probably don’t care about in a smaller, italicized font. Even then, this article may be a yawn to most parrot owners – I got deeper into feathers than most veterinarians do during my days working with penguins, display macaws and cockatoos at SeaWorld.

I focused this article on parrots. But since no scientific experiments use parrots as their subjects, I have had to use my personal observations and to reach out for information to birds that have been studied. Fortunately, the basic mechanisms and life processes are very similar between birds. Current research on how feathers develop is centered at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and Arizona State University. The US NIH funds this research because of its interest in how human body organs might be regenerated. They have all told me that there are big gaps in what we know about the molt process.

What Are Feathers Composed Of?

Although feathers start out alive as pinfeathers, when they are fully formed, like your hair, they are dead and cannot be repaired. When the shaft of a feather on your bird is still alive, it will have a purple-blue color and it will bleed profusely if it gets injured.

Scientists who study feathers give different types of body feathers different names. The longest feathers of the wings are called primary feathers or flight feathers, the shorter wing feathers, secondary feathers. Together, they are called remiges. The base of these wing feathers are covered with shorter ones called coverts. Tail feathers are called retrices. The feathers that cover the bird’s body and give it its shape are called contour feathers. Under the contour body feathers are the fluffy down feathers that provide insulation.

The central shaft of the feather is composed of a hollow base – called the quill or calamus and the remaining portion of the shaft called the rachis. The feathery sides or vane are composed of individual barbs, which are, themselves, covered with smaller barbules that keep them “zippered” together. The fluffy base portion is called the afterfeather.

Does Molt Occur In An Orderly Fashion?

Yes. All birds loose their feathers symmetrically. That means that when one or two feathers are lost and replaced on one wing, the same feathers are lost and replaced on the other. This allows birds to continue to fly balanced while they are molting. By only loosing a few body feathers at a time, the bird also stays protected from the chill of rain and cold air.

What Causes Parrots And Other Birds To Molt?

What causes birds to molt has intrigued scientists for years. Parrots have the same molt mechanisms that all birds share. It is a very complex process that has been difficult to sort out and fully understand.

Some birds live in harsh climates or depend on food sources that are only available periodically. These birds have evolved to have their molts at exactly to the right season – when food is plentiful, their babies have flown away and the weather is mild. Parrots are less exacting because they come from areas where the temperature is tropical all year long and food is always available. But the basic mechanism of parrot feather molt remains the same.

It has only been in the last few years that the process has begun to be understood. Normal molt has nothing to do with temperature or new feathers pushing out old ones. It has everything to do with a natural hormonal rhythm that all birds maintain.

The Rhythms Of Life That Govern Molt

It may surprise you that deep inside your parrot there is a clock. All birds have one. It is called their diurnal, circadian or photoperiodic clock and it keeps track of the hours of the day. It is also a calendar (circannual) clock, in that it keeps very accurate track of the month of the year.

The clock is like a personal secretary. It informs the bird when it is the right time to breed, the best time to change feathers (molt), and, in some bird species other than parrots, the best time to fly south for the winter (no, birds don’t fly South like Daffy because they are cold).

The bird’s circadian clock ticks from birth. But to remain accurate over time, it hands need to be fine-tuned from clues obtained from the environment around it. It receives these clues in the form of sunlight and the length of the days. The process of resetting the clock to exact time is called entrainment.

What Winds The Clock?

The circadian clock responds best to certain wavelengths of light and also, to some extent, to the light’s intensity. But most important, it seems, is the shape of the light-length curve during the year.

Ordinary white sunlight or ‘full spectrum light’ contains all the colors of the rainbow. But within this rainbow of colors, the circadian clock responds best to red light (about 640nm).

Many parrot owners believe that parrots should shed a feather now and then. When I lived in San Antonio, TX, I had redheaded amazon parrots in my home as pets. They did loose feathers now and then. But I also had a flock of breeding redheaded amazon parrots in outdoor flights. They all lost their feathers over the course of a month, shortly after they raised their chicks. They bred at the same time, laid eggs at the same time and molted at the same time. The difference was the light the two different groups received. My house pets had lights on until the family went to bed. The lighting was ordinary lamp light – not full spectrum light and its intensity was variable. So their circadian clocks became free-running. The outdoor birds relied on natural sunlight so their clocks kept better time.

The annual cycle in birds begins with breeding. Lengthening spring days – sensed by the clock – trigger their annual reproductive and molt cycles. Once the process has started, the clock cannot be reset until a period of short, winter days, have passed. (photorefractoriness)

The closer one gets to the equator, the less difference there is between the length of summer and winter days. Parrots are not as “disciplined” in obeying their calendar clocks as some other bird species. That is probably because they live in areas where food is usually plentiful and daylight hours do not vary as much by season. But avian circadian clocks are very sensitive. Even a 30 minute difference in daylight hours is noticeable to some birds. Even birds that live dead-on on the equator in South America or Africa experience seasonal variations in light intensity that affect their reproductive and molt cycles – there is less sunshine during their rainy season.

Australian cockatoos time their reproductive subsequent molt cycles to lengthening spring and summer days. Parrots of Mexico and Central America tend to molt in long late summer days. Hyacinth macaws Brazil’s Pantanal, where 90% live, begin their breeding and subsequent molt in July through December while African Gray parrots in the Congo river basin tend to begin their annual reproductive and molt cycle at the beginning of the dry season (July – December) when more sunny days occur.

Where Is This Clock? – The Pineal Gland

The circadian clock in birds resides in its pineal gland. This is a small organ that sits near the front of its brain. Within the pineal gland is a group of cells that chemically oscillate, that is they “tick” and keep pace like a musical metronome. . Even if these cells are removed from the bird and placed in a test tube, they continue to pulse.

The pineal gland is “wired” to the eyes to “perceive” light and probably senses light in other ways as well. Humans also have a pineal gland. But our pineal glands work in a different manner – it is not as “independent ” as the ones birds have.

The way I have explained this is an oversimplification . Understanding molt is a bit like peeling an onion – remove one layer and you find another. It is a much more complex process involving lots of chemicals, many of them poorly understood.

Humans and other mammals also have a circadian clock. But it has moved to another location in our brain.

How Often Do Parrots Normally Molt Their Feathers ?

That depends. Indoor parrots that receive artificial light have extended molt periods and they may have several per year. They may also retain certain feathers for over a year. That is because their clock is free–running and no longer precise.

However, my double-yellow head and red headed amazons, blue and gold and greenwing macaws, Quaker parrots and lovebirds that were exposed to natural sunlight in Texas molted one time, late in the summer. I cannot tell you about outdoor cockatoos or other parrots because I have not personally owned them.

Black cockatoos are said to take two years to complete a molt. But I do not know if these were indoor or outdoor birds. To accurately know when wild parrots drop feathers is an almost impossible task. I would love for anyone who might have this information to share it with me.

Wild Cockatiels are said to have two molts – one before breeding and one after fledging their young.

Over the year, sunlight slightly bleaches feathers, the color of the new ones are more intense. This makes it easier to tell which feathers are the newest.

Because breeding and molt are intimately connected through the same hormonal cycles, it is my suspicion that small parrot that breed more than once a year probably go through multiple molts as well.

Is There An Order In Which The Feathers Fall Out?

Yes. When feathers are molted normally, an equal number are lost on both sides of the body. There are no bald patches and the new pinfeathers appear quickly. In that way, the bird continues to have the ability to fly in balance, old feathers protect the new blood-filled pinfeathers from damage and the bird can maintain its body temperature. This is most apparent with wing feathers and is the reason you need to examine de-flighted pets frequently to be sure the clipped feathers have not been replaced. Primary wing feathers are often the first to fall out during a molt. Usually, the inner ones fall first. Then the secondary flight feathers and tail feathers start being lost and replaced, followed by the contour feathers.

Do New Feathers Push The Old Feathers Out?

It is not that simple. The key to new feather formation is the removal of the old feather. In some unclear way, the presence of a well-anchored feather prevents a new feather from forming. When that feather loosens or is plucked out, a new feather immediately begins to form.

Prior to molting the blood vessels supporting feather growth dry up and feather attachment to the surrounding tissue becomes loosened.

When you pluck out a parrots feather, the process begins. But in a natural molt, at least in some bird species, the feather bud or follicle begins producing the new feather before the old one is completely shed. So, in a sense, the new feather does give the final push-out to the old one. Ref 2

Do We Know What Hormones and Chemical Factors Are Involved In Molt?

We know what hormones are in play when molt occurs. But we do not know the process by which they cause old feathers to fall and new feathers to replace them.

Cytokine (chemokines)

Cytokines are messenger proteins that carry signals locally between cells. These signaling molecules used extensively by birds in cellular communication. Unlike hormones – they concentrate locally and are active in lower concentration. These signaling chemicals have been found to increase when molt begins – just like they do when hair is shed and regrown. Whether they function to dislodge the old feather or grow a new feather or If they are the actual cause of the molting process remains unknown. 2nd ref. Similar factors are involved in the growth of hair.

Melatonin

Melatonin tells the bird when to molt. But it does not cause feathers to fall out or regrow. It is the primary hormone produced by the pineal gland. It is also called the time keeper hormone because oscillations its production and secretion that are timed to the amount of light that is present are the body’s central timekeeper . Its presence or absence controls the production of all other hormones involved in reproduction and molt as well as all differences between day and night time activities. Melatonin is secreted when it is dark . Daily melatonin production is longest in the winter when nights are long and shortest in summer when nights are short. But blood melatonin reaches its highest daily peaks in the spring and summer when days are lengthening and its lowest peaks in the fall and winter.

Melatonin rhythm and amplitude govern the production of many hormones produced in the bird’s pituitary gland. These include FSH, LH and Prolactin, which are involved in nesting and reproduction, ACTH, which controls adrenal gland hormone production, TSH, which controls thyroid hormone production and GH which controls growth.

LH (Luteinizing Hormone aka Interstitial Cell Stimulating Hormone or ICSH)

In female birds, this hormone stimulates ovulation. In male birds, it stimulates testosterone production. In response to lowering levels of pineal-produced melatonin in the lengthening springtime days, blood levels of LH in birds increase and trigger their reproductive cycle.

As their reproductive cycle ends the LH levels of birds decline. This decline occurs concurrent with their molt.

Prolactin (PRL) or Luteotropic hormone (LTH)

Prolactin is another hormone produced by the bird’s pituitary gland under the control of the pineal gland. Some studies indicate that prolactin levels are highest in the period that birds begin their molt while others have reached the opposite conclusion.

Progesterone is produced by the ovaries of birds as they go through their reproductive period.

When I worked with penguins, one of my biggest problem was failure of the birds to molt. Birds that did not molt also did not reproduce, so I suspected that their problem was due to the way the artificial light they received affected their circadian rhythms. I found that the only hormone that would cause these birds to go through a normal molt was a long-acting form of progesterone called Depopovera. This may have occurred because progesterone is known affect the blood LH level of birds.

Thyroxine (thyroid hormone)

I do not believe that thyroid hormone causes molt. Some veterinarians associate molt problems with thyroid problems. This is because birds that have had their thyroid glands removed have a number of problems – including the inability to molt normally.

Thyroid hormone level goes up when feathers are being formed. But this hormone rises whenever the body must synthesize proteins. Another reason it is associated with molt is that giving high levels of thyroxine causes chickens to molt. Chicken growers call thyroxine “the natural molting hormone” – but this is not so.

To get the chickens to molt, they must feed, near-toxic levels of thyroxine. Natural high-end blood levels don’t cause molt. Just about anything, given at toxic levels, will cause a bird to molt. This includes zinc, cotton seed meal containing gossypol ). Thyroxine also goes up when birds are cold due to their lost feathers.

Will My Parrot’s Personality Change While It Molts?

If your parrot lives indoors in artificial light and molts only an occasional feather, its personality will not change. If your parrot has gone through a normal summer breeding cycle during which its sexual hormones surged, it will quiet down and become less aggressive during its subsequent molting period.

Many parrots become less active and moody while molting. Your pet may not be as affectionate with you as it normally is. Parrots will scratch themselves more as the new contour and head feathers sprout.

Pin Feathers

Immature feathers are called pin feathers or blood feathers because they are still living tissue. Because they are growing so fast, pin feathers contain a great deal of blood, which gives them their dark, bluish color.

How Should I Deal With A Bleeding Pin Feather ?

Pin feathers bleed when they are damaged. This occurs, most often when new feathers replaced clipped ones of the bird’s wing. In a natural molt, mature feathers protect the erupting pin feather from damage as the bird flaps its wings. But when the wing is clipped, the new feather is unprotected and often becomes crimped or damaged. Bleeding feathers also occur when the parrots chews on their feathers as a way of relieving stress and boredom.

Damaged pin feathers will not heal on their own. They will continue to bleed when they are moved or disturbed. So you need to pulled or plucked out the damaged pin feather or bring it to a veterinarian or experienced aviculturalist if the task is beyond your abilities. Removing the damaged feather can be quite painful to the bird if it is not done quickly and purposefully. If you are squeamish about it, let someone with more experience do it.

Here is what you should do or should have done:

1) Your parrot needs to be restrained in such a way that it cannot bite or claw you but in a way that allows it to breath freely.

2) With forceps (hemostats) or some other grasping instrument, the feather needs to be grasped as close to the bird’s skin as possible and then plucked out. Tweezers are unsuitable except for the smallest birds.

3) Hold pressure on the area for a minute or two after extracting the damaged feather shaft to allow time for clotting to occur.

If a damaged pin feather is allowed to remain, it will, at best, mature distorted. A worse development is when the bird chews on the stump sufficiently to cause an ingrown feather. These must be removed surgically and often the feather follicle is lost or must be removed in the process.

Before a parrot’s wings are clipped, each feather needs to be examined to be sure an immature pin feather is not going to be cut. If one is found, delay clipping the wing until the feather is fully mature and the quill has lightened to the color of the adjoining feathers.

If a parrot continues to damage erupting wing feathers, I sometimes “imp” the birds. This is a falconry technique in which I place old mature feathers in the remaining cut quills that surround the blood feather. Elmer’s™ glue holds them in place long enough for the blood feather to mature and harden.

Powder Down

The ordinary downy feathers of parrots insulate them from cold and heat. But cockatoos, cockatiels and African gray parrots , in particular, have a specialized down that naturally disintegrates to form fine lubricating and waterproofing dust. These feathers grow and regenerate continuously and their powder is spread over all the feathers as the bird preens.

Does My Parrot Require Special Care During Molt?

Feathers make up a considerable portion of your birds weight and take lots of energy to regenerate during molt. So , next to the rearing of young, your pet’s nutritional and metabolic needs are greatest during a full molt. Molt is also a period when stress to the bird’s body is increased.

Your parrot should have no problem undergoing a normal molt if it is fed a balanced diet. Molt is often the time when large parrots feed unbalanced, sun flower and safflower seed diets or small parrots fed primarily millet , run into trouble. That is why I suggest you feed a name brand pelleted parrot diet.

Be sure your pet’s environment is not excessively hot or cold.

Most parrots enjoy being misted off with a spray bottle all year long. But they seem to especially enjoy it during molt. Be sure your pets toenails are not over grown because the bird will be scratching itself as the itchy pin feathers begin to mature.

Normally, mature parrots are pair-bonded to a mate who helps groom and remove the feather sheaths from new feathers the bird can not reach. You can gently roll these new head and neck feathers with your fingers to accomplish the same thing.

There will be a lot of extra dander and scale that you will need to vacuum up. It is also helpful to install an HVAC (AC/Heating filter) with an MERV 11 rating or better.

Preening

Feathers are complex structures that require constant care called preening. Preening removes dirt, spreads the bird’s body oils and realigns the feather’s structure. It is also a social activity between birds and their mates and owners. Most parrots have an oil or preen gland (uropygial gland) situated at the base of their tail which is the source of most of their feather oil. Without this oil, the feathers will absorb rainwater and the bird will be unable to fly or maintain its normal body temperature.

What Do My Parrots Feathers Tell Me About My Parrots General Health?

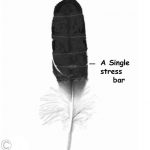

Just like the hair coats of our dogs and cats mirror their general health, the feathers of our pet parrots tell us a lot about their general well-being. If your parrots feather colors are dull or off-color, if they are broken or have stress bars or if they fail to develop normally the bird is not in good over-all health.

The biggest cause of poor feathering is malnutrition due to the bird consuming an unbalanced diet. Even if you are feeding a balanced diet, parrots often pick through it, eating only the things that catch their fancy.

Other chronic diseases of parrots also lead to abnormal feathers. These include a number of bacterial, viral, fungal and parasitic problems.

What Are Some Causes Of Abnormal Molt?

The most common cause of abnormally molt cycles is artificial lighting that is out of sync with the normal sunrise and sunset of the season.

The most common cause of abnormal feather formation is poor diet. Another common cause of poor feathering is chronic stress.

The molting process is a major strain on your pet’s body, drawing on the bird’s protein and caloric reserves. Latent (silent) health problems often become apparent during, or shortly after molting.

The Merck Veterinary Manual gives a good overview of the diseases that parrots sometimes develop. All of them can weaken the bird sufficiently to interfere with normal feather growth. To an untrained eye, incomplete molt or feather picking can be confused with a much more serious problem – psittacine beak and feather disease (PBFD). The most unusual molts I have witnessed are the climax molt of the penguins I have cared for. Mine used to go off into a corner of the exhibit, look quite depressed and forlorn, go off their feed, swell up enormously with fluid (subcutaneous edema) and then, within a period of two days, completely replace their feathers! I had to cut off all their wing bands before their molts because they got tight enough to impede circulation due to the natural swelling. The reason penguins have the most dramatic of all bird molts, is that they would freeze if they stayed naked any longer than a day or two in the sub-an arctic cold. Parrots aren’t nearly that dramatic. They loose a feather here and a feather there. One of the great mysteries and miracles of Nature, I know of, is that they loose the same feather on the opposite wing just about he time the same one falls out of the other wing. The same thing happens in most bird species Nature is just so amazing. Macaws and parrots would probably have a more even molt if they only saw natural lighting. In their wild tropical setting, the whole hormonal cycle – leading to molt -starts when the days begin to lengthen. But most of us have our birds indoors with artificial light, which complicates matters.

French Molt (BFD, Polyoma Virus, APV)

French molt is an old term dating to the 1870s when parakeet (budgerigar) breeders in France noticed budgie offspring that never developed proper feathers or developed them quite late. When they were sold in England they called them runners, creepers or bullets.

We now know that French molt is the result of a virus that attacks many parts of the body. In some cases, the immature birds die suddenly. In others, they either clear the virus or go on to become permanent, silent carriers of the virus. But some survive no longer able produce proper feathers. In mild cases, the flight feathers of the wing and tail are the only ones that fail to form.

The responsible virus is a polyoma virus. (polyomavirus) of birds. It is also called the Budgerigar Fledgling Disease Virus (BFDV). It also appears that many species of parrots, other than parakeets are susceptible. However, different species of parrots may have their own particular strains of the virus.

Laboratory tests are available to detect this virus. I prefer the PCR (2nd lab) test over other serological methods because of its greater sensitivity . However, even the PCR test will not identify birds damaged by the virus that are not currently actively shedding it.

A vaccine against avian polyomavirus has been developed. I believe that it has been over-sold to the avian pet community since mature parrots have a strong natural resistance to infection. The vaccine has its practical use – but that is at bird breeding facilities where the virus is continuously present. Even in those situations, proper bird husbandry is more effective in eliminating a polyomavirus problem than is vaccination. You can read one of the scientific articles that describe bird polyoma viruses here.

Psittacine Beak and Feather, Feather-Beak Disease (PBFD)

This is the only disease of parrots that directly affects feathers. Read about this disease in detail here. It is caused by a circovirus. All parrots appear susceptible, but it is seen most commonly in cockatoos, African Gray Parrots, macaws, ringneck parakeets, lovebirds and eclectus parrots.

Parrots with this problem produce weak, twisted feathers that rapidly break off or are plucked out. They also often suffer from abnormal beak, and sometimes, abnormal claw growth. Their immune systems eventually fail. The disease, once it is established, is incurable but carrier parrots that shed the virus can look perfectly normal. A test for PBFD is available (2nd lab).

What Causes Bars Or Stress Lines On My Parrot’s Feathers?

Feather grows requires a constant blood level of nutrients. If a baby parrot is off feed for even a half day during the time its feathers are forming – you will see a “stress bar (fault bar or fault line) on the feathers that were most actively growing at the time. Improper temperature and other stressors can also lead to this problem.

This is a little line across the feather – as if it had been scored, marked or cut with a scissors at that point. The area of the stress bar is weak, translucent and easily torn. When multiple bars form, each bar represents a period of stress. It is quite difficult to hand raise baby parrots without a few stress bars forming. In subsequent natural molts, normal feathers will replace them. But when they occur in mature birds, they are warning bars. An avian veterinarian needs to be consulted to determine the underlying cause.

Feather Picking, Feather Plucking And Abnormal Molts

Parrots should have smooth sleek plumage – not puffs of down sticking outward, a frazzled look or patchy missing or chewed off feathers.

All feather damage that parrots inflict on themselves begins as over-preening. It occurs in all degrees. Sometimes the cause is simple boredom. Parrots are very gregarious birds that are happiest in Nature when they are in large groups. They do not handle loneliness well at all. The only time parrots do not hang out in groups is when they are raising their young. So you have a great responsibility fulfilling their social needs.

In other cases, it is due to a poor diet, high-stress environment or underlying disease. Much like some people bite their fingernails to overcome stress, over-grooming is a common way that parrots cope with boredom, stressed and poor nutrition.

Cockatoos and African Gray parrots are highly emotional and more subject to stress and loneliness-induced feather picking than other more “laid back” parrots. Some parrots over groom during the agitation of their reproductive season or the loss of an owner to which they were bonded.

The first step parrot owners should take if they notice feather problems is to return the pet’s environment to how it was before the problem became apparent. The next step should be to put the bird on a well-regarded pelleted diet if it is not already receiving one.

Increased light, particularly natural sunlight is always positive as long as the bird does not overheat and is given normal dark nights.

These modifications need to be done early into the problem. Parrots are creatures of habit. Once over-grooming progresses to an obsession, it can be a very difficult habit to break – even if the initiating cause is eliminated. In these cases, the parrot may need to wear an Elizabethan collar for a while.

Masking these problems with drugs is rarely effective. The only ones I have found effective are those that lower sex steroids when agitation is due to the parrots reproductive season. (eg GnRH). Sometimes, returning the bird to an outdoor flight with other parrots of its same species is the only effective remedy.

Some owners suspect their parrot might have skin parasites causing itchiness and over preening. This is almost never the case when individual, long time pet birds are affected. Many internal diseases can be the root cause of feather plucking and abnormal molts. Older birds need to be screened for liver disease, abdominal tumors, egg yolk peritonitis, hypothyroidism, ingestion of toxic products (zinc toxicity) and other possible health issues.

Simple Things You Can Do

1) Feed a name brand, pelleted diet.

2) Spend more time interacting with your pet.

3) If you would become bored sitting all day in a cage similar to your pet’s , the parrot will become just as bored and frustrated.

4) Expose it to more natural sunlight or Grow lights (Full-spectrum lamps, UVA & UVB) that are set to be on in sync with natural day length.

5) Be sure room temperature is neither too warm, too cold or too dry.

Keep a non-toxic potted plant growing in the room. If the plant is not thriving, your parrot won’t either. My favorites are chemically untreated, ornamental pepper plants.

6) Keep the pet where it has visual contact with family members it is bonded to.

7) Be sure it has a large, spacious cage with climbing areas. Cages are never too large.

8) Have plenty of large diameter perches going at different angles.

9) Do not place its cage near air vents or in stressful areas of the house.

10) Allow the bird (with properly clipped wings and no predatory dogs or cats) to spend time on top of its cage or on a T-post.

11) Expose the bird to TV programs it seems to enjoy.

12) Give it plenty of safe objects to gnaw on and crack open.

13) Turn the lights off at night.

14) Don’t throw a cover over your pet or move its cage when it squawks.

15) Keep your parrot’s environment as dust free as possible by frequently changing your HVAC filters and using high efficiency ones; and by vacuuming frequently (with the parrot out of ear range).

16) Mist your parrot off frequently with a plant spray bottle. If the bird is fearful and cringes back, begin slowly and offer it food rewards and encouragement. If it enjoys bathing, give it a shallow pan to bath in.

Diet And Abnormal Molts

Poor diet and poor feathers go hand in glove together. Parrots are like children – lay out a balanced, nutritious diet in front of them and they will pick through it for the high fat, high sugar items and push the other stuff aside. Here in Northern Mexico, the parrots with the best plumage are the ones owned by impoverished families who feed their pets a bit of whatever they consume and the ones flying around free that eat whatever fruit and bids that are in season. They have never seen sunflower seeds, safflower seeds or millet. The saddest are the ones that hang in restaurants and hotels where uninformed employees feeds them seeds from time to time.

For individual pet owners, the basic diet for their pet should to be a name brand, pelleted diet sold especially for parrots. I suggest to my clients that these commercial diets make up 75% of your birds total food consumption. Of course, it is possible to prepare an equally nutritious diet completely from individual ingredients. But you must be careful that all of it is consumed in proper amounts and this is difficult if you do not make a special point of it. Many of the things parrots love – like nuts, peanuts and oil seeds are not healthy when too much is consumed. And items like apple, lettuce, and banana are basically empty calories devoid of proteins necessary to make good feathers. Fresh produce must also be carefully washed to rid it of the potential of salmonella and similar bacteria.

There is absolutely no need for supplements , tonics and molting formulas if the bird is eating a balanced diet and there is no excuse for your pet not eating a balanced diet. I have been quite satisfied with parrot diets produced by Zupreme, Mazuri and Roudybush. Harrison’s diets have also been fine. Avoid smaller companies and niche products available from only a small number of distributors because these companies do not have the resources for strict batch-to-batch quality control. Be sure you are not sold old stock that has sat on the shelf or feed and pet store stock that has been exposed to rodents.

Do Some Parrots Have Allergies That Cause Them To Itch and Pull Out Their Feathers?

Whether true allergies occurs in parrots is subject to debate. Certainly, smoke, perfumes, fumes and home cleaners can irritate and bother your pet. But these are not true allergies. Basically, avoid these products for your own health as well as your pet’s. When parrots scratch themselves, they are assumed to be itchy. But most parrots that pull out their feathers do not spend much time scratching. If they do scratch, examine the humidity of your home, the possibility of internal disease and some of the other factors I have gone over before worrying about true allergies.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website