All About Oxalate Bladder And Kidney Stones In Your Dog – Cystic and Renal Calculi

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Struvite bladder stones in your dog

Struvite bladder stones in your dog

Plump dogs might be at greater risk?

Plump dogs might be at greater risk?

The two words, kidney stones and kidney calculi, are interchangeable

What Is Oxalate, And Why Has It Formed Stones In My Dog’s Urinary Tract?

Oxalate stones in your dog’s urinary tract are one of the most exasperating problems that veterinarians deal with. That is because they are nearly impossible to medically dissolve. In test tubes they will dissolve – but not at a safe acidity.

Oxalic acid, the compound they are formed from, is created when carbohydrates your dog eats are metabolized. Your dog’s normal liver metabolism also generates some. When oxalic acid finds itself in the presence of calcium, it has the ability to link to it, forming insoluble crystals of calcium oxalate. In humans, about 20-50% is thought to come from our diet and the rest manufactured “in house”. In dogs the percentages are unknown. Oxalates do not appear to have any useful function in you or your dog’s the body; they are just a metabolic waste destined to leave the body through our urine – much like urea (BUN).

Why Did My Dog Form Calcium Oxalate Stones In It Bladder Or Kidneys?

A small amount of calcium oxalate is present in all urine. It is only when it is present in abnormally high amounts, when the urine is very concentrated or when other factors (e.g. crystallization kinetics) favor the growth of these crystals into sizable stones that they become a medical problem. (read here) How all these factors interplay is not well understood in dogs or humans. (read here & here) We do know that dogs that form calcium oxalate stones tends to have acidic urine (when a liquid is acidic, its pH is under 7 – but not always.

Your dog’s genetics come into play too. When two or more dogs live in the same household, eating the same food and living the same lifestyle, it is unusual for more than one of them to develop an oxalate stone problem. Veterinarians and physician have written countless articles on the subject, but they have never been able to tell you more than the cause is probably a combination of many individual things (multifactorial). “Multifactorial” is just a scholarly way of saying ‘there must be causes, but I don’t know what they are”. Their veterinary advice continues to be “make as many changes in your pet’s nutrition and lifestyle as you can that might (theoretically) slow oxalate crystal formation. But despite following that advice, many dogs will go on to reform oxalate urinary tract stones. Some will not; and some dogs that made no changes in their lifestyle whatsoever will never have an oxalate stone relapse again.

Certain breeds seem more susceptible (bichon, schnauzers, etc.) – but genetics cannot account for the greatly increased number of oxalate-affected pets veterinarians have seen in all dog breeds and cats since 1981. I believe that only nutritional and lifestyle factors could account for that.

What Are The Signs I Might See If My Dog Has Oxalate Stones?

The signs will vary depending on whether the stones are present in your dog’s kidneys, bladder or both. They will be very sudden and severe if a small stone has moved downstream from your pet’s kidney and lodged in one of its ureters or moved downstream from its bladder and lodged in its urethra.

The most common sign owners notice is difficulty urinating. Dogs with a urinary tract stone issue often take longer to urinate and attempt to urinate more frequently. The amount of urine they pass with each voiding is often less, and they will maintain a squatting or leg-cocked position longer after they no longer have urine to void. Some spend excess time licking their genital area subsequent to urination. Dog owners often notice that the final drops of urine are pinkish rather than normal yellow. At that stage, only a few dogs show physical distress or colicky signs. Most do not. The next most common way stones are discovered is when dogs are x-rayed – either for vague signs of abdominal discomfort (e.g. colic, flank pain, a suspected urinary tract infection) or seen on the x-rays when radiographed for some entirely different problem.

When oxalate stones have been present in your dog’s kidneys for long periods, but remained unnoticed, the pet may come to its veterinarian already uremic, due to the damage the stones have already caused to its kidneys. The porous nature of kidney stones are an invitation to bacteria and infection. When they block the exit of urine, they also cause pressure within the kidney to build up, doing damage to the fragile filters kidneys contain.

None of these symptoms are specific to oxalate kidney or bladder stones – other types of urinary tract stones and abnormalities and infections of the kidneys, bladder or tubes that link them (ureters and urethra) cause identical signs. Dogs, particularly male ones, with repeat UTIs should be scrutinized particularly closely for the presence of urinary tract stones.

Is One Dog More Susceptible To Oxalate Stones Than Another?

Although female dogs are susceptible to oxalate stones, many more are diagnosed in male dogs. More cases occur in midlife (5-9 years) than in younger or very old dogs. More cases occur in small and toy breeds than in the large dog breeds (other than keeshonds). In order of frequency in one California study, the breeds with the highest frequency of calcium oxalate stones were Bichon Frisé, Miniature Schnauzer, Shih Tzu, Lhasa Apso, Pomeranian, Cairn terrier, Yorkshire terrier, Maltese and Keeshonds. Breeds with the lowest frequency of calcium oxalate stones were German Shorthair pointers, Great Danes, Rottweilers, Australian Cattle Dogs, Labrador Retrievers, German Shepherds, Border Collies and Bull Mastiffs. Read the statistics in Canada here.

Don’t assume that these statistics are entirely due to genetics. The small dog breeds that show the greatest incidence of oxalate stones are also among the most popular breeds today. So, there are more of them from which to submit samples. Also, the lifestyle of small breeds tends to be quite different from the lifestyle of larger breeds. Larger breeds tend to spend more time outside where there is greater opportunity to urinate frequently throughout the day.

How Will My Veterinarian Decide If My Dog Has An Oxalate Stone Problem?

Your Veterinarian’s Physical Examination

The history you provide to your veterinarian is quite important. Its symptoms will most probably lead your vet to suspect that your pet’s problem involves its urinary tract. Over their careers, veterinarians become quite astute at probing and palpating the tummies of pets. They can feel many things through the walls of your pet’s abdomen that might not be apparent to you. Some dogs are much easier to palpate (feel) than others. Fat dogs, large dogs, anxious dogs and dogs that are tense due to pain (splinting) are much harder to palpate. Your veterinarian might notice that your pet is tensing its abdomen due to pain and that the area of its kidneys or bladder appears to be the most sensitive.

Your veterinarian will be able to palpate your pet’s bladder. When bladders are chronically inflamed by stones or infection, they become thicker than normal. If a large stone(s) is located in your pet’s bladder and the dog is relaxed enough, your vet will probably feel it. When several stones are loose in the bladder, they often grind together during palpation – similar to a handful of marbles.

When a small stone has blocked the urethra, leading from the bladder to the penis in male dogs, the vet can sometimes palpate it through the rectum wall using a finger cot.

In smaller leaner dogs, the kidneys can usually be palpated as well. When those kidneys are abnormally large or small or lumpy or hard, or unequal size, your vet knows that something is amiss.

At that point, most veterinarians are going to want to do two things: examine your pet’s urine and x-ray its urinary tract.

X-rays

One or two x-ray views of your dog’s abdomen are usually enough to detect oxalate urinary stones when they are present. Both of the most common stone constituents, oxalate and struvite, have a density similar to bone, so these more-or-less round objects are relatively easy to detect. Other forms of urinary stones (urate, phosphate or cystine) can be much harder to see (less radiopaque).

Survey x-rays do not detect all urinary tract stones. Very small ones can be missed when only a few are present. The same problem occurs when other structures and colon contents obscure a small stone that has lodged in the dog’s urethra or ureter. In those situations, your vet might decide that an enema prior to x-rays would be helpful.

If stones still can’t be seen, but your vet still suspects them, more complicated and sensitive, techniques like double contrast cystoscopy technique shown in this image are available:

Your Pet’s Urine Specimen Checked

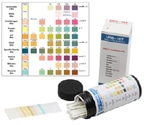

All veterinary hospitals have small reagent strips that give a color indication of the things that are present in urine. In most cases of urinary tract stones, these strips will indicate the presence of blood in your dog’s urine. They may also be positive for the presence of nitrite and white blood cells – indications of a urinary tract infection. The strips also indicate the acidity (pH) of your pet’s urine. If the pH of your dog’s urine is less than 6.5, it might make your veterinarian suspicious that the stones are composed of oxalate. Some strips also give a crude measurement of the concentration of your dog’s urine (specific gravity = SG). However, pH and specific gravity during a crisis are not good indications of what your pet’s day-to-day urine characteristics are.

Your veterinarian will also centrifuge the urine specimen and examine the sediment that forms on the bottom of the tube. The presence of an abnormally high number of white blood cells confirms urinary tract infection or inflammation and small crystals of oxalate or other stone-forming elements can often be seen as well. Although bacteria play an important role in the formation of struvite stones, they do not appear to be an important factor in the formation of oxalate stones. When they are observed in an oxalate stone case, bacteria are just taking refuge in the stones and taking advantaged of a traumatized bladder.

Stone Analysis

If your pet managed to pass a stone or if stones were removed from your pet in some other manner, they will most likely be sent on to the Minnesota Urolith Center to determine what they are made of. That is the only sure way to tell one type of urinary tract stone from another. It is important to have them sent off because the treatment for each type of urinary tract stone is different. Occasionally, the results will indicate that your pet has formed compound stones that contain elements of more than one common type. In that case, it will need treatments directed at both.

Can Oxalate Stones Become A Medical Emergency?

Yes, they can.

Your dog always needs to be able to pass its urine freely. If the tubes leading from each of its kidneys to the bladder (the ureters) or urethra, the tube leading from the bladder to the penis or vagina are blocked, your pet’s condition will deteriorate rapidly. Dogs rely on urination to regulate their body’s water content, blood ions (electrolytes) balance, body acidity and in eliminating the toxic waste products of their metabolism. The most common crisis situation scenario is a male dog with a stone present in its bladder that is just small enough to enter its urethra – but not small enough to pass through the narrow portions surrounded by its os penis.

If this blockage lasts more than the greater part of a day, one of these blood ions, potassium, that is normally excreted through its urine, can reach dangerously high levels. Abnormally high potassium levels (hyperkalemia) affects the ability of the dog’s heart to beat normally (cardiac arrhythmias). Obstructed dogs quickly become depressed and weak. They usually experience nausea and vomit. When partially or fully obstructed dogs are left untreated, the abnormally high pressure of urine behind the obstruction leads to rapid irreversible destruction of the pet’s kidneys.

In male dogs that have repeat episodes of this problem, a surgical procedure called a perineal urethrostomy can be performed that vents the urine from your pet’s bladder and urethra before it passes through the penile bone where they usually lodge. (in the os penis).

Female dogs have a urethra that is wider and shorter than males. So, they become urethra-obstructed considerably less frequently than males. The trade-off is that their shorter wider urethra makes them considerably more likely to develop UTIs.

How Can I Make Oxalate Stones Go Away?

The unfortunate reality is that veterinarians have nothing that will dissolve calcium oxalate stones in your dog’s urinary tract. Calcium oxalate will dissolve – but only in solutions too alkaline for the dog’s body to tolerate. So, most calcium oxalate stones will need to be removed from your pet surgically.

Urohydropropulsion

When dogs are very fortunate, a single small stone or cluster of stones can be removed through a non-surgical technique called urohydropropulsion. In that technique, the natural elasticity of the urethra under forceful urine flow is used to allow small stones present in the dog’s bladder or urethra to make their way out via the urethra – much like a water balloon jet increases the diameter of the balloon’s neck when you squirt someone at a party. Saline solutions are passed up a catheter, passed the stone(s) and into the pet’s bladder to provide the liquid volume needed. The technique works best in dogs weighing more than 18-20 pounds and when the estimated diameter of the calculi is no greater than 5 mm. Dogs need to be anesthetized and held in a position so that gravity assists in increasing the force of the urine stream. The technique is more successful in female dogs than males. It is not without hazard because it is possible to rupture the bladder if pathology has weakened its walls or if the procedure is performed too forcefully. You can read about that procedure here. Most of the case I have dealt with had just too many small stones for this procedure to be of value. Every one of the stones moving down the urethra does a little bid more damage to its lining. So generally, your veterinarian will already have his/her surgical instrument packs sterilized and at the ready to go in surgically to remove the stones should the urohydropropulsion procedure fail (in highly advanced facilities, that back up procedure will likely be a laser).

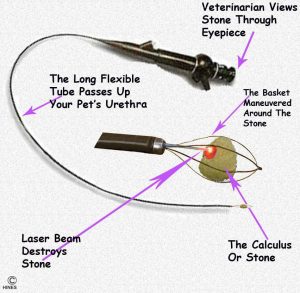

Cystoscopy

When dogs are large enough to allow the passage of instruments up the urethra and into the bladder, it is sometimes possible to nibble away or crush bladder stones into fragments small enough to leave the pet naturally in its urine or net them up in a small basket-like apparatus and draw them out the urethra in that way. It is not a technique you will find performed by veterinarians in general practice; it is performed by specialists at a number of university veterinary hospitals. Some of those Centers are listed in the next section on Lithotripsy. When a dog is cat-size and the diameter of the urinary tract tubes are too narrow, the dog’s bladder can be approached through tiny skin incisions (percutaneously) and instruments used like chopsticks. (read here)

Surgery

The majority of dogs with calcium oxalate bladder stones must undergo surgery to have them removed. It is the simplest, and most direct way to deal with them and the techniques to do it are available at surgical centers throughout the USA and Europe. Luckily, the majority of calcium oxalate calculi form in the bladder (about 90%) which is the most accessible area. Unless your pet has multiple health issues, the surgery to remove them from the bladder is straightforward and recovery is rapid.

Removal of any type of urinary tract stone is much more difficult when they are present in your dog’s kidneys and ureters. The decision to do so or to let matters remain as they are is best left up to an experienced, board-certified veterinary surgeon experienced in those matters. There are only a few of them in the United States. I send the pets of most of the dog owners that write to me to the AMC in Manhattan because their urology department is superb. In the UK, I send these cases to the Royal Veterinary College. Because these cases are so complex and the techniques so difficult to master, there is likely to be disagreement on the best options. At a minimum, the insertion of a stent might be considered when a particular stone threatens to block a ureter. Stents take the immediacy out of the situation by giving urine alternative ways to exit.

The smaller the dog, the more delicate kidney or ureteral surgery becomes. Decisions are also based on the stone(s) location within the pet’s kidneys and any evidence that the calculi are obstructing urine flow. Other factors that enter into the decision as to removal of kidney stones (those actually in the kidney) are the frequency of urinary tract infections, the shape, size and number of stones, the rate at which they are increasing in size and the number of times the problem has reoccurred after prior surgeries.

Larger calcium oxalate stones, found in the bladder, are often mixed with sandy grit composed of the same material. When this grit is present in your dog’s bladder, the lining of the bladder will be highly inflamed and thickened. That makes it quite difficult to find and remove every last grain of calcium oxalate. Any that remain after surgery serve as seeds for new calculi to develop. Veterinarians must be extremely careful to flush out every last grain of that material. But even then, up to 20% of the time they will miss a few. You can read about the decisions that went into the determination in a single case here: (read here)

Lithotripsy

Lithotripsy is a procedure whereby urinary tract stones are broken up (fragmented) into pieces small enough to pass out of the pet’s body – either naturally or with assistance. It avoids large surgical incisions and in some cases, any surgery at all.

There was a time when shock waves, directed from outside the body and focused on kidney stones, were the most popular method of treating kidney stones in humans. It was also attempted in cats and dogs. But with time, it became apparent that the technique was too traumatic to the kidneys and surrounding structures.

The most commonly technique that is used today is probably an apparatus called a holmium YAG laser. In this procedure, the conduit conveying the laser’s energy is inserted up the pet’s urinary tract until it is in direct contact with the stone.

When I did a survey some years ago, there were less than ten veterinarians worldwide who were competent to perform this procedure. All were in the US and Canada. Although the Royal Veterinary College, London, expressed an interest in providing the procedure, they had not done so at the time.

At the time, laser lithotripsy was available at the AMC, The University of California Veterinary School in Davis, The University of Minnesota Veterinary School’s, Minnesota Urolith Center, the Veterinary School at Purdue University and the Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tufts. It was also performed then at the veterinary school in Montreal and in Guelph. Veterinary surgeons move on in their careers. Their interests change. Their funding sources change. So today, I am sure the locations involved in your dog’s treatment options and the people involved have changed.

Should I Consider Other Options Instead of Those High-tech Procedures?

In most cases a skillful veterinary surgeon can remove urinary tract stones from your pet’s lower urinary tract with similar success rates to lithotripsies. However, there are cases when the locations of the calculi, their size and consistency or the general health of your dog or your geographic location might make laser lithotripsy the preferable option. Those decisions have to be made on a case-by-case basis by the veterinarians handling your case.

Will My Dog Form New Stones After Surgery?

If you do not make major changes in your pet’s lifestyle and nutrition, the likelihood of your pet reforming oxalate stones is quite high. Somewhere around half of the dogs that experience one incidence of calcium oxalate stones will go on to have another attack within three years. It will take considerably more than just feeding a commercial prescription diets purported to prevent oxalate stone formation to change those odds.

Long-Term Follow Up:

Periodic Urinalysis

Your veterinarian will want to analyze your pet’s urine periodically. Some veterinarians recommend that as frequently as every two months, indefinitely. The vet will be particularly interested in your pet’s urine pH, urine specific gravity or any indication of blood or infection. The vet will also look at the sediment present in the dog’s urine specimen for any signs of returning oxalate crystals.

The best urine to bring in for those tests is the first urine of the day – before your dog has eaten. It should be free of contamination, refrigerated or chilled and brought to the animal hospital as rapidly as possible. A foam cup, taped to a broomstick helps in collection. You do not need much – a tablespoon-full will do. You can also attempt to get your pet to pee on a layer of Saran Wrap™ and transfer what you can to a cup. Cover the sample with a piece of Saran Wrap held in place with a rubber band or ask your vet for a urine collection vial.

Dog owners who are not health professionals or biologists are unlikely to be able to accurately identify crystals or bacteria microscopically. But you can learn to perform some of these simple but critical tests yourself. Owners who perform simple reagent strip tests at home are more likely to test their pets frequently, and so they are more likely to have better outcomes. You can buy them online or at your local pharmacy. No prescription is needed.

What Can I Do To Prevent Oxalate Stones From Reoccurring In My Dog?

I have no foolproof plan to guarantee that your dog will not produce oxalate stones again. That is because no veterinarian knows for certain why some dogs develop these stones and others do not. What veterinarians can do is use their general knowledge of oxalate chemistry and dog metabolism to accomplish things we hope might be helpful in preventing a relapse in your dog:

The Importance Of Water Consumption

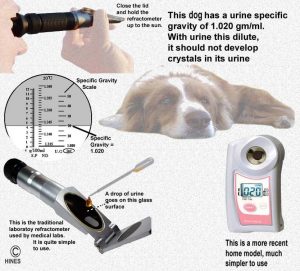

Increased water consumption = dilute urine. From what we know about calcium oxalate, it is very unlikely to crystallize into discrete, urinary tract stones when your pet’s urine is dilute – even if particles of oxalate are present at the time. A Waltham study found that breeds of dogs that generally drink more, form less oxalate stones than breeds that drink less (e.g. miniature schnauzers vs Labrador retrievers) – although one cannot say for sure that one influences the other. (read here) Observations at the University of Minnesota were similar. There are several ways that you can increase your dog’s water consumption. They include feeding your dog only canned, frozen or home-cooked diets, moderately increasing the amount of salt in your dog’s diet, and, in carefully chosen cases, administering diuretic medications like hydrochlorothiazide. There is a section on each of those options below. You will only know you are succeeding by measuring the specific gravity of your pet’s urine at home on multiple occasions. For that, you need to purchase a urine refractometer. eBay is as good a place as any. They run about $30.

In addition, all dogs need easy access to clean, fresh water throughout the day. Multi-dog families should have multiple water bowls.

Your Dog’s Urine Specific Gravity

Because the most important things you can do to prevent all forms of urinary stones from reoccurring is to keep your dog well hydrated, and it’s urine as dilute as possible, you need to take special care to monitor it. We measure the degree of dilution of urine by its Specific Gravity. The lower the specific gravity, the more dilute the urine sample is. Aim at keeping your pet’s urine specific gravity below 1.025. Because low specific gravity is so critical, it is safer to measure it with a specific device called a refractometer, rather than to rely on the readings obtained from paper Multistix® and similar urine dipstick strips.

I encourage all my clients with stone-forming pets to purchase a refractometer. Do not be intimidated by the gizmo’s name or weird construction – it will not bite, and it is very easy to use. Once you get the hang of it, your readings will be as accurate as any PhD biochemist. Just be sure the instrument has been calibrated to zero with distilled water and that you are reading the specific gravity scale (SG), not the serum protein (SP) scale. You can read more about urine refractometers and urine specific gravity here & here. Be sure to purchase one designed for medical use, not for candy making.

Urine pH

Oxalate stones only form in urine that is acidic. Veterinarians measure acidity by recording urine pH. It is normal for dog urine to be acidic (pH less than 7 = acidic). Dogs are carnivores, and all carnivore urine is acidic. Urine that is too basic (pH more than 7) brings its own set of problems. Most dogs that initially come to veterinarians with oxalate stone problems have a urine pH of 6.5 or less. You need to make changes in your pet’s nutrition and lifestyle that keep its urine pH consistently higher than that. I suggest aiming at 6.8, but recommendations vary greatly between veterinarians. Urine pH is another test you can easily perform at home using urine dipsticks or color-indicator paper. The sample to check is the first fresh void of the morning. Urine pH varies during the day. After your pet has eaten breakfast, its urine pH will begin to rise from its nighttime levels. You may not be successful in keeping your pet’s urine pH where you want it. When you can’t, be content in knowing that dilute urine probably trumps less acidic urine. That is, it is probably more important to keep your pet’s urine dilute than it is to raise its urine pH.

Frequent Opportunities to Urinate

Dogs that are free to urinate whenever they wish appear to be less susceptible to oxalate bladder stones than dogs that must wait for their owners to return home from work. Fewer urinations and lower urine quantities were found to be associated with greater potential for oxalate stone formation (RSS index). (read here & here)

Lack of opportunities to pee throughout the day might also account for the fact that dogs in urban Toronto have a significantly greater incidence of oxalate bladder stones than those that live in the surrounding rural areas. (read here)

Frequent Smaller Feedings

The acidity level (pH) of your dog’s urine fluctuates during the day. It is usually lowest during the night and then slowly rises after the pet’s morning meal (postprandial alkaline tide). (read here) So having many chances to munch during the day should give your pet a urine pH profile that is less acidic and therefore, less conducive to oxalate stone formation. Give your dog its last meal shortly before you go to bed. Just be sure that the total amount you feed your pet does not increase. I do not want your dog to become overweight. Frequent small feedings might also minimize the postprandial (after meals) increase in urinary calcium that is thought by some to occur. (read here)

Monitor RSS = Relative Supersaturation

Much of my advice about preventing oxalate urinary tract stones relies on research conducted at the Waltham Centre For Pet Nutrition in Waltham-on-the-Wolds, Leicestershire, UK. The Center conducted nutritional research on dogs and cats there and funded promising projects elsewhere. Unfortunately, it and Royal Canin are all part of the Mars Candy Bar Conglomerate now. I believe that their objectivity and independent pioneering spirit have waned under the pernicious influence of corporate profit objectives (the pursuit of money).

In an attempt to predict oxalate stone formation before it occurred, Waltham pioneered the use of relative supersaturation (RSS) testing in pets. RSS testing predicts when conditions in your pet’s urine are conducive to stone formation and when they are not. That is critical information to know because it allows you to decide if the changes you have made to your pet’s diet and lifestyle are working. If you plan to prepare your dog’s meals at home, RSS and a standard urinalysis are a good way to see if you are staying on track. If you feed a commercial canned diet designed to prevent oxalate stones, RSS and urinalysis are a good way to decide which brand is working best for your dog. Although RSS makes sense theoretically, there are no scientific studies to prove it actually works in dogs or humans. Although this is a great test, there is one problem – no US labs that I know of offer it for dogs or cats.

Periodic Blood Work

It is always prudent to run standard blood chemistry panels on your dog from time to time. This is especially true when oxalate stones remain in your dog’s kidneys or when there was any prior elevation of blood BUN or creatinine levels.

There are a few dogs that develop oxalate stones because their blood calcium levels are abnormally high (hypercalcemia). Some of these dogs have underlying hyperthyroidism problems. Keeshonds are noted for that issue – but it can occur for a number of reasons and in any dog. (read here)

Periodic Radiographs

Periodic x-rays are important in detecting new calculi that might be forming in your dog and in judging the growth and position of calculi that have not been removed. When calculi are discovered early, it might be possible to removed them from the bladder through urohydropropulsion or extract them in a retrieval basket through the urethra or through a very small abdominal and bladder incision.

Are There Medications That Might Help?

Potassium Citrate

Veterinarians have traditionally dispensed potassium citrate solutions to dogs that have developed oxalate stones. The hope was that when the citrate passed out in the dog’s urine, it would tie up urine calcium making it unavailable for calcium oxalate formation. It was also hoped that the citrate would keep the urine less acidic. Some studies make it unclear if that theory holds up. Certainly, to have a continuous effect, the potassium citrate would have to be given many times during the day. If not, it would probably be best to give the largest portion of their daily dose at bedtime because we suspect that nighttime conditions are most conducive to stone formation.

Thiazide Diuretics

I mentioned that keeping your dog’s urine specific gravity under 1.025 was very important in preventing reoccurrence of stones because all forms of urinary tract stones are less likely to form in dilute urine. When you cannot achieve that with canned or fresh diets and water supplementation, some veterinarians resort to medications that make your pet thirstier and urinate more. These are the diuretics. The most commonly used non-thiazide diuretic, furosemide is not used because it is known to increase the calcium content of urine – something we do not want. So, some veterinarians give these pets thiazide diuretics. The most common one used for this purpose is hydrochlorothiazide. No medication is without risk. I would not administer diuretics to dogs with calcium oxalate problems unless less drastic diet changes and increased fluid intake measures had failed. While on thiazide diuretics, your pet’s blood electrolytes ought to be monitored.

Will My Dog Need A Special Diet From Now On?

Special diets will not dissolve calcium oxalate stones that have already formed. But dogs that have had an episode of calcium oxalate bladder or kidney stones have special needs. They should not be fed dry dog chow again, and they should not receive a diet that contains plant products that are high in oxalates.

You can purchase many diets from your veterinarian that were designed, theoretically, to reduce the likelihood of calcium oxalate urinary tract stones. Whether these diets actually work, is unknown. They are all formulated to provide as little dietary oxalate as possible, provide no more than the necessary amounts of calcium and attempt to keep your pet’s urine pH and specific gravity in acceptable ranges. If you determine, through urinalysis, that those diets are doing that, they are fine. If not, there is no need for them in addressing an oxalate urinary stone problem. These diets have been a godsend for dealing with struvite stones; but they are not nearly as effective in managing oxalate stones.

You can also prepare your dog’s diet at home. Read about that here. I suggest you have certified veterinary nutritionists such as those at BalanceIT prepare your recipes. Most dogs that develop oxalate problems are small, so you do not have to prepare large quantities. The diet you prepare will then contain the same quality ingredients that you eat.

Red meat, chicken and turkey are quite low in oxalate. Organ meats, like liver, are higher because much of the oxalate formed in the body is produced in the liver. It is probably best not to feed your dog products that contain soy or yellow corn or ingredients that are derived from corn. Corn glutens have the potential to make your pet’s urine too acidic. Soybean products have the potential to be very high in oxalates. Raw diets are probably not a good idea for pets with oxalate urinary tract stones. Boiling, and discarding the water that was used, greatly reduces the amount of absorbable oxalate in vegetables and grains. (read here)

If I Prepare My Dog’s Diet At Home, Should I restrict Its Calcium Content?

That is probably not a good idea. Calcium Oxalate does require free urine calcium to form. So for a long time, both physicians and veterinarians thought that restricting dietary calcium would help prevent oxalate stones. That theory did not hold up.

Why Have The Number Of Oxalate Calculi Risen So Dramatically Over The Last 30 Years?

One reason is probably that the lifestyles of owners and pets have also changed dramatically over the last 30 years. There has been a shift to smaller breeds, that appear to be more susceptible to the problem and more owners are working full time and unable to provide spaced intervals for their dogs to urinate and exercise during the day. We know that lack of exercise predisposes humans to calcium oxalate calculi. (read here) Perhaps it affects dogs similarly.

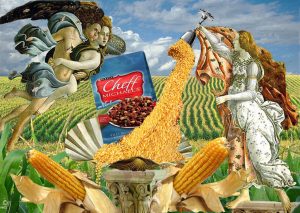

But there is another reason. It is the pet food industry itself. The last 30 years have seen two important changes in that industry. Conglomeration into a few mega-firms that dominate the World pet food market, a worldwide explosion of demand for prepared pet foods and intense competition for limited animal protein resources (meat-based products that go into pet food). So pet food conglomerates have become experts at serving up iffy food ingredients wrapped in fancy labels and delivered with snazzy TV ad campaigns featuring wolves for dog foods and lynx for cat foods. But accountants and marketers drive the train – not staff nutritionists or veterinarians. Let’s look at the ingredients in a bag of popular Nestlé’s (aka Purina) product, Chef Michael’s. It’s no better and no worse than the other mass-market dog foods you find at your retailer.

Let’s take Chef Michael’s Filet Mignon Flavor Dry Dog Food for example: 32% protein, 18% fat and about 42% carbohydrates. All dog owners know their pets like meat protein – so that looks good. Besides, you’ve seen the ad on TV with the Chef cutting up that good-looking rib eye! The food ingredients are listed according to their weight in the finished product – the largest ingredient first. You see that its ingredients are: Beef, soybean meal, soy flour, animal fat, brewers rice, soy protein concentrate, corn gluten meal, ground yellow corn, glycerin, poultry by-product meal, ground wheat, animal digest, salt, pearled barley, natural filet mignon flavor, dried potatoes and dried green beans. The rest of the ingredients are food dyes, vitamins, minerals, preservatives and flavorants.

Beef is listed as the first ingredient – that sounds good. But beef is 65-75% water and the other ingredients are dry. So, they are not comparing apples to apples. If you considered the beef more accurately – as to how much it contributed to the dry mix – it would be way down the list. But these companies know that pet owners like to see meat as the first ingredient and there is no USDA rule against this slight-of-hand. The soybean meal and soy flour are actually the primary ingredients that Chef Michael puts in his dog food – but you don’t see Chef Michael cutting up soybeans or corn. Soy is known to be very high in oxalate. (read here). The soybeans are added to help make this a high-protein product while still retaining a high enough profit margin. There is debate as to whether soy protein is inferior to meat protein. (read here & here) But there is no debate in that soy products are very high in oxalate.

Brewer’s rice is a byproduct of human rice cultivation – not something in beer. It is made up of the culled, broken grains resulting from the rice milling process (the fragments that pass through a #4 sieve but not a 2.5 sieve). It is added to keep the meat to the front of the ingredient list and the corn products lower down. It also adds starch necessary to form the extruded pellet. Corn gluten meal is a byproduct obtained when corn is processed into ethanol for your car or corn syrup. It is a traditional ingredient in cattle feed. Gluten has also been associated with increased urinary tract stones in dogs. (read here) Animal digests, meat and bone meal are the products of rendering plants and slaughterhouses. There is no telling what their oxalate content might be. But a lot of USDA condemned livers and organ meats, the carcass parts containing the most oxalate, end up in the brew. (read here & here) That is because up to 78% of pig livers are condemned due to roundworm parasite scars. With dog owners waking up to the negative effects of corn, pet food companies have rapidly shifted to “grain free” formulas. However, they have no intention of actually decreasing carbohydrate load. In substituting non-grain carbohydrates like potatoes, peas and lentils for the corn, they appear to have increased the chances of your dog developing even greater health issues (e.g. cardiomyopathies).

Are There Any Medications My Dog Should Avoid After Developing An Oxalate Stone Problem?

Yes.

Veterinarians would like to keep as much calcium out of your pet’s urine as possible. A common diuretic, furosemide (Lasix®) increases the calcium content of urine. Most dogs receive it for chronic heart problems. If your dog is a known stone-former, perhaps your vet would consider a thiazide diuretic like chlorothiazide or hydrochlorothiazide, although neither of them are entirely free of potential side effects either. When dogs receive diuretics, their dangers of becoming dehydrated increase if drinking water is not always available. Dehydration causes your dog’s urine to be more concentrated. As you know if you have read this far, concentrated urine is something stone-forming dogs need to avoid.

Some dogs receive steroid medications for chronic inflammatory conditions or itching. One of the minor side effects of these medications (prednisone, dexamethasone, etc.) can be increased calcium excretion into the urine. Some dogs have no choice but to receive long-term or intermittent steroids. But any dog that can avoid it with another option, should. A similar effect can occur in dogs with Cushing’s disease that produce too much of these compounds on its own.

Supplements containing vitamin C, excessive vitamin D or excessive amounts of calcium should probably not be given to dogs that have a tendency to form calcium oxalate urinary tract stones.

Diets designed to prevent struvite urinary stones appear to, on occasion, make pets more susceptible to oxalate stones. There was a time when these diets were formulated to produce a markedly acidic urine. When oxalate stones began to increase in frequency, these diets were reformulated to come closer to a neutral pH (=pH 7). Today, it is more likely that dogs that develop oxalate stones on those diets just aren’t drinking enough (use canned dog food if you can, add water if you can’t).

Bichon Frisé

Some veterinarians think of oxalate stones as the “little white dog” syndrome. That is not entirely true, but Bichon Frisé develop more than their share of calcium oxalate urinary tract stones. More than half of the calculi this breed develops are the struvite kind. But calcium oxalate and mixed constituent stones form most of the rest. As in all dogs, males are more likely to form stones and for those stones to be oxalate. They also have a sad tendency to reoccur in this breed. There are no special ways to protect Bichons from re-occurrence other than the ones I mentioned – just be very aggressive in keeping your dog’s urine dilute and feeding it properly.

Oxalobacter formigenes?

Some time ago, human urologists became interested in a fragile obscure bacteria that inhabits the large intestine of humans and many animals. That bacteria, Oxalobacter, was capable of destroying oxalate. In fact, oxalate was what it lived on. A study appeared to indicate that humans with oxalate stone problems were less likely to have a population of these bacteria. (read here) One theory was that prior antibiotic use (e.g. ciprofloxacin, a cousin of Batryl®) might have killed off the bacteria, making those people more susceptible to oxalate urinary tract stones. The oxalobacter bacteria are also present in some dogs. Whether or not the presence or absence of oxalobacter plays any part in dog or in human oxalate calculi formation remains unknown. Some studies suggest it might (read here) and some that it might not. (read here)

**************************************************************************************************

It might turn out that some of my suggestion are unnecessary. It might turn out that some are ineffective. But until veterinarians understand why some dogs form calcium oxalate stones on one diets and lifestyle, while others with that same diet and lifestyle do not, this is the best advice we can offer.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.