Adrenal Gland Tumors In Your Ferret – Why They Happen – What They Do – Your Treatment Options

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Adrenal gland tumors and pre-cancerous similar adrenal issues (aka Adrenal-associated endocrinopathies=AAE), along with lymphoma, are the two most serious diseases that face middle-aged and elderly ferrets. Because ferrets have shorter lifespans than dogs and cats, adrenal gland disease and other diseases associated with aging begin in ferrets earlier than you might expect (@3-4 years). (read here) (that said, most of the ferrets that veterinarians see with symptoms of adrenal gland tumors are older than 5yrs).

Many ferret owners believe that adrenal gland illnesses affect male and female ferrets equally. But most studies I know of found that female ferrets have a moderately increased risk when compared to males. (read here)

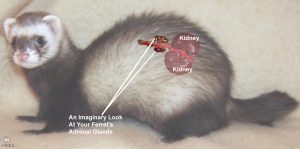

Your ferret has two adrenal glands – one just anterior to each kidney. Each of these endocrine glands has an inner and an outer portion. Each portion has a different responsibility. The inner portion, the medulla, produces the short-term stress-related hormones epinephrine, norepinephrine and dopamine. The outer portion or cortex produces a mixture of different hormones. The most prevalent one is cortisol. But various specialized cells within the adrenal cortex layers also have the capacity to produces a mixture of sex and reproductive hormones – all under the direction of your ferret’s pituitary gland. It is this outer cortical layer that is subject to tumors that over-secrete sex and reproductive hormones.

Why Do Ferrets Frequently Get These Adrenal Gland Tumors?

Why Do Ferrets Frequently Get These Adrenal Gland Tumors?

It is very unlikely that the root of this problem lies in your ferret’s adrenal glands. The problem is much more likely due to a miscommunication between your pet’s pituitary gland and its adrenal glands. Adrenal glands (the outer cortex layers of each gland) are “pluripotent” organs. That is, they have the ability to shift gears and produce various hormones when the pituitary gland believes that those compounds are desirable. It directs the adrenal gland cortices to alter the amounts and types of hormones it manufactures through messenger compounds (like GnRH). The pituitary gland and adjacent hypothalamus continuously monitor your ferret’s entire endocrine system and modify their output of signaling/messenger compounds according to perceived need.

There are many similarities between this disease in ferrets and the most common form of Cushing’s disease in dogs and humans. (read here) In all three, it is communication between the pituitary gland and the adrenal gland that is involved (the “pituitary/adrenal axis”). In dogs and humans, it is often a tumor of the pituitary gland that causes that organ to emit an excessive amount of a particular messenger chemical (ACTH) that tells the adrenal glands to produce more cortisone (more than it should). Many veterinarians believe that in ferrets, it is spaying and castration and the resulting lack of the feedback hormones, estrogen and testosterone from the missing ovaries and testicles that cause the ferret’s pituitary to send messenger chemicals to the missing sex organs in an attempt to get them to produce more testosterone or estrogen. The pituitary gland has no way of knowing that those organs were surgically removed and just assumes those organs are “sleeping on the job”. Those same messenger chemicals, circulating in the blood, are also recognized by the ferret’s adrenal glands. As I mentioned, adrenal glands also have the capacity to produce estrogen and testosterone-like sex hormones as well as hormones associated with reproduction when instructed to do so by the pituitary. Many veterinarians currently believe that these tumors form in your ferret’s adrenal glands due to this pituitary messenger chemical over-stimulation.

Much is still unknown and/or controversial when it comes to this disease in ferrets. Some believe that if ferrets were neutered later in life (most American-bred ferrets are neutered as infants ~6wks), we would see less of the disease. (read here) Others believe that the lack of testes or ovaries at any age has the potential to cause adrenal gland-related problems. Others point to the fact that most ferrets live indoors where lighting and light quality do not mimic (do not correspond to) natural daylight and seasonal cycles. Still others theorize that inbreeding or ferret strain has an influence on the likelihood of this disease developing. That is based on the fact that less of this problem is said to occur in Europe and the UK when many more ferrets are housed out of doors, neutered later in life if at all and fed prey animals rather than commercial ferret chows. Still others point to the possible presence of endocrine disrupting chemicals in the foods ferrets eat and are exposed to. (read here) Definitive studies that might help sort things out take a lot of time and money. Unless ferrets become considerably more popular as pets, it is doubtful to me that they will be performed.

So it could be that a number of factors interact to influence the likelihood that your ferret will develop this disease, the severity of the disease when it occurs and the effectiveness of specific treatment options veterinarians have to offer. That is the case with most every disease we and our pets face.

What Are The Signs Of Adrenal Gland Disease In Ferrets?

What Are The Signs Of Adrenal Gland Disease In Ferrets?

The first sign that something is amiss is usually thinning hair near the tip of your ferret’s tail and sometimes increased scratching (in vetspeak “bilateral progressive alopecia accompanied by pruritus”).

Hair loss and scratching can occur in ferrets for a number of other reasons. Fleas can cause it; so can mange, ringworm, dry skin, exposure to irritating dust and chemicals or allergies. But hair loss due to adrenal gland problems is always distinctively symmetrical – that is, occurring in the same area and pattern on both sides of the ferret’s body. As time goes by, hair also fails to grow over the ferret’s back, flanks and stomach. Hair loss can eventually reach the pet’s neck and shoulders. It is not so much that the hair is prematurely falling out. It is that it is not being replaced after its normal lifespan on the body. It also wears off at the points on the body that the ferret rubs and scratches the most.

In spayed females, the area surrounding the vagina (its vulva) usually becomes puffy due to too much adrenal gland estrogen in her system. Vaginal seepages sometimes occur. Male ferrets with adrenal gland problems often have difficulty passing their urine due to an enlarged prostate gland (stranguria). Their prostate gland enlarges due to excessive adrenal gland-produced androgens. The backup of urine pressure this produces can affect their kidneys – occasionally causing those organs to fail. (read here)

The increased male sex hormones being released from the pet’s overactive adrenal glands have also been associated with mood changes in ferrets (increased aggression). These ferrets do not appear to be in pain although some seem less energetic than they once where. Many loose muscle mass – especially in their thighs and pelvic area. Other signs, such as liver issues, have been reported. But there is no clear evidence that those signs were tied to the pet’s adrenal gland problems. Multiple health problems often coexist in our pets.

How Will My Veterinarian Diagnose This Problem?

How Will My Veterinarian Diagnose This Problem?

Your veterinarian’s traditional tests for adrenal and pituitary disease in dogs are not very helpful in diagnosing adrenal tumors or pre-tumor adrenal/pituitary states in ferrets. But the signs I mentioned above are generally sufficient for your veterinarian to make the diagnosis.

In some cases, blood tests show anemia. High estrogen levels tend to produce that. When anemia is severe in a younger female ferret, the possibility that a portion of the pet’s ovaries accidentally remained after surgery also needs to be considered. In other ferrets white blood cell numbers are also decreased (= pancytopenia).

Larger adrenal tumors or abnormally large adrenal gland(s) can also occasionally be visualized in ultrasound examinations – particularly if the professional performing the examination is well versed in ferret anatomy. When the left adrenal gland is enlarged, your veterinarian can sometimes feel it (palpate it) with his/her fingers. The right adrenal gland , when not markedly enlarged, is a bit too far anterior in the body to be reliably palpated.

If your veterinarian feels that it is necessary, a serum sample from you ferret can be sent to the diagnostic services of the Veterinary College at the University of Tennessee for confirmation that your ferret’s sex steroid blood levels are abnormally high.

Your Ferret’s Medical Treatment Options:

Your Ferret’s Medical Treatment Options:

There are a mixed class of medications with similar effects called gonadotrophic releasing hormone antagonists and agonists (GnRH antagonists). Both effectively shut down or greatly reduce the pituitary gland’s ability to produce the various hormones associated with reproduction by tying up GnRH receptors on target organs or tumors. These compounds were initially developed in a search for novel ways to treat inoperable prostate cancer in men. Most of my experience using them in ferrets is with leuprolide acetate (read here) and goserelin, but the one most frequently given to ferrets today is deslorelin (Suprelorin F®). It is marketed for dogs (and more recently approved for ferrets) by Virbac Animal Health. These medications often need to be repeated every 4-6 months to control hormonally-driven diseases – although Virbac claims that the positive effects of a single deslorelin slow-release implant can last as long as a year.

Because there are so many variations in what messenger chemicals a ferret’s pituitary gland might be producing in excess as well as variations in the disease process in each individual ferret, the effectiveness of these “anti-hormone” medications vary greatly between pets. Also, with time, it is a characteristic of many tumors to “learn” to escape the beneficial effects of drugs that once controlled their growth. Some report that that is also the case in ferrets given GnRH inhibitors such as deslorelin.

Mitotane (Lysodren®)

Mitotane (Lysodren®)

Mitotane (Lysodren®), a drug used to treat Cushing’s disease in dogs and a similar drug, trilostane (Vetoryl®) are also options. (read here) Although they are considerably less expensive than the GnRH inhibitors, they are considerably more prone to producing side effects. Other medications have been tried in the past. Melatonin was thought by some to be helpful. It is a compound that plays a part in regulating the pituitary gland’s daily and seasonal hormone production. I am told that anastrozole, a compound that blocks male hormones (androgens) from converting to estrogens, has been tried in the past. Other vets have attempted to treat cases with ketoconazole due to its suppressive effects on the adrenal gland’s production of reproductive hormones and cortisol. (read here) None of these treatments have proven to be particularly effective.

The Surgical Option:

The Surgical Option:

No medications veterinarians have today will cure adrenal tumors in ferrets. But I suggest a medical options over surgery for ferrets that are already in generally frail health due to the disease’s progress, or when your ferret is of advanced age, or when concurrent health issues or financial constraints are issues to be dealt with. When none of those issues exist, or when medications cease to be effective, some ferrets do have a surgical option. When surgery removes all visible tumors, it is often presented as being “curative”. However, that is not really the case because tumors begin very small – no more than a microscopic accumulation of a few cells which cannot currently be detected. Also, the underlying driver of future tumor formation and growth (ie no gonads) will still remain.

When tumors are only present in your ferrets left adrenal gland, those large enough to be visible can be removed or the entire left gland removed (ferrets can survive with only one adrenal gland). The right adrenal gland is much harder for veterinary surgeons to approach and the risk of injuring adjacent structures in that adrenal gland is much greater. It is also questionable if one adrenal gland would be tumorous and the other completely healthy, since they are both exposed to the same excess of pituitary hormones. It is also unknown if ferrets that have their adrenal tumors removed surgically live any longer than ferrets managed medically.

Why Do Ferrets Frequently Get These Adrenal Gland Tumors?

Why Do Ferrets Frequently Get These Adrenal Gland Tumors?  What Are The Signs Of Adrenal Gland Disease In Ferrets?

What Are The Signs Of Adrenal Gland Disease In Ferrets? How Will My Veterinarian Diagnose This Problem?

How Will My Veterinarian Diagnose This Problem? Your Ferret’s Medical Treatment Options:

Your Ferret’s Medical Treatment Options: Mitotane (Lysodren®)

Mitotane (Lysodren®) The Surgical Option:

The Surgical Option: Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that Google chooses to display on this webpage helps me pay the cost of keeping this article on the Web. As you know, sites like mine that are not designed to make money are getting harder and harder to find. Best wishes, Ron Hines

Dear reader, Besides your donations, Visiting the products that Google chooses to display on this webpage helps me pay the cost of keeping this article on the Web. As you know, sites like mine that are not designed to make money are getting harder and harder to find. Best wishes, Ron Hines