Knee Problems In Your Dog – Patellar Luxation

Luxating Kneecaps

Ron Hines DVM PhD

What Is A Luxating Patella Problem?

When the structures that make up your pet’s knees (its stifles) are misaligned or misshapen, a problem called “trick knee” or patellar luxation can be the result. Your pet’s kneecaps are a very important component of a normally functioning knee joint. These kneecaps (= patella) are meant to ride in a groove on the forward face of the femur. The patella acts as a pulley, giving leverage to extend the leg as your pet walks.

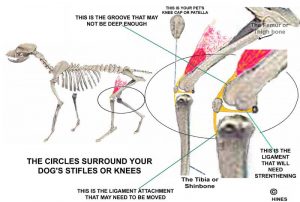

Click on the drawing of the bones and ligaments of your pet’s knee at the top of the page. The oval kneecap should rides smoothly in a groove (the trochlear groove or fossa) over the front of the femur, (the largest bone of the thigh). From the end of the patella nearest your dog’s body, a strong ligament/tendon (I drew in yellow) (or see here) anchors the patella to the largest muscles of the thigh. On the other end, a similar ligament attaches the patella to a prominence (tuberosity) on the pet’s shinbone or tibia. Two other alignment ligaments (the collateral ligaments) located on the inner (medial patellar ligaments) and outer side (lateral patellar ligaments) of the knee keep the patella gilding in its track. When your dog has popping knees, those two side ligaments are not doing their job – the patella is popping out (luxating) from its normal tract. In over 90% of the cases in dogs and the occasional cat that develops the problem, the patella jumps out of its tract to the inside of your pet’s knee (medial patellar luxation=MPL).

This problem is one of the five most common genetic (birth defect) anatomical problems veterinarians see in dogs. (read here) Three structural bone and tendon abnormalities in your pet leg lead to it:

The first abnormality that is usually present is a trochlear groove (the notch the patella rides in) that is too shallow. In order for the patella not to jump out of this tract, the groove must be deep enough to accommodate and cradle the patella as it slides up and down in the groove. Some dogs are born with an abnormally shallow trochlear groove. Veterinarians do not know why.

The second problem is probably a result of the first. It is a weakened and stretched lateral patellar ligament. Again, although only one knee may appear to be affected, in most cases, both knees of your pet share this problem to some degree.

The third problem occurs when the lower attachment of the kneecap ligament is too far to the inner side of the shinbone or tibia. This is a frequent problem in dogs that are bred to have exceptionally short legs (like dachshunds). When dogs develop luxating patellas before the tibia has reached maturity, it is also possible for this lower point of attachment to shift inward – throwing off the entire joint alignment.

One or all of these three problems are responsible for your pet’s knee locking up as it walks. These problems were not present when your pet was born. They resulted from this group of abnormalities involving your pet’s entire hind limb that slowly change the contour of the bones as the puppy grew. You can read about that here.

On very rare occasions, patellar problems are the result of direct or strain-injuries to the knee cap or accidental trauma to the knee joint that tore the collateral ligaments that keep the patella moving in line.

Is The Problem More Common In Some Breeds Than Others?

Yes.

Luxating patellas are quite common in pomeranians, dachshunds, toy and miniature poodles. Yorkshire terriers and Boston bulldogs are high on the list as well. It is also seen occasionally in boykin spaniels, cocker spaniels, chow chows, bedlington terriers, Australian terriers, Japanese chin, Shar-Pei, Mi-ki, Lhasa apsos, Tibetans spaniels, Tibetan terriers, and Labrador retrievers (more or less in that order of frequency).

Tiny dogs are thought to be about 12 times more likely to have luxating patellas (=MPL=medial patella luxation, medial means to the inside) than larger breeds. It is common for these small breeds to be about three years old before their knees begin to lock up, and their owners become concerned. You can read more about some of these little dogs with special, more complicated knee problem that involve their cruciate ligament ligament as well as their patella here.

There are veterinarians who believe that knee problems, particularly when they occur in larger dogs, actually start as hip problems. You can read a UK study that discusses that here. In another UK report, Labrador retrievers constituted the bulk of the large-dog patellar luxation problems. You can read about how those cases were handled and what their outcomes were here.

What Signs Would I See If My Dog Has A Luxating Patella Problem?

The signs you will see in your dog depend on how severe the problem is and how long the problem has been going on.

Most owners just notice that their pet begins to occasionally skip when it runs. There is no sign that there is any pain – your dog just doesn’t let one rear leg touch the ground as it runs or walks. Then, after a few steps, the leg usually returns to normal and the pet seems unconcerned.

In other dogs, owners notice a pop while the pet is shifting around on the owner’s lap or being handled. It is quite often a groomers or your veterinarian that first bring the problem to the owner’s attention. Knee caps that have the potential to pop out of their groove do so most readily when the knee is fully extended. Many vets, me included, always check for the potential of the problem in toy breeds on the client’s first visit. With the leg fully extended, moderate inward thumb pressure on the patella of an at-risk dog will usually pop it out of its groove. This must never be done forcefully.

I mentioned that many owners remain unconcerned about their dog skipping until it becomes an almost constant problem at around three years of age. But many toy breeds are no more than six months old when their gait problems first begin. When knee structures are seriously out of line, it has been known to occur as early as 8-10 weeks. The parents of those dog almost certainly had the trait as well. Many breeders of toy dogs just shrug it off as “normal”.

Patellar luxation is often divided into four grades of seriousness or severity. There is quite a bit of subjectivity (decision leeway) in deciding when a pet moves from one stage to the next:

Grade #1

Grade one pets do not experience pain. Their kneecap pops out of place intermittently and can be easily massaged back into place when the leg is fully extended.

Grade #2

Grade II pets have less stable knees. The kneecap can be massaged back into its groove – but it pops back out again once the knee is manually flexed or after the pet has taken a few steps. With time, many of these pets will develop knee pain and arthritis associated with their problem.

Grade #3

Dogs in which the problem is still intermittent but more frequent or when accompanied by pain or arthritic changes belong in grade 3.

Grade #4

These are pets whose kneecap will not stay in its groove even for short periods. These dogs have a hard time walking. Dogs that have suffered this degree of joint damage for more than a year or two usually have pain, developing arthritis and degenerative joint disease. They usually walk with a crouching stance and stand knock-kneed with their toes turned inward.

Grade 3 & 4 dogs never walk entirely normally. Although their problem was generally present early in their life, they may not be brought to a veterinarian for the problem until they reached middle-aged. In these severe, advanced patellar luxation cases, changes are occurring that you cannot see or feel. The slick, bony surfaces of the patella and trochlear groove have become inflamed and eroded in a process called chondromalacia. At time passes, this inflammation becomes more generalized to eventually involve most of the supportive cartilage and fibrous tissues of the knee. Surgery in these more advanced cases is less likely to be successful or to stop the progression of arthritis of the joint. You can read more about that here. It is also not uncommon for one of the cruciate ligaments of the pet’s knee to eventually tear. Although I am not a fan of the TPLO procedure, it has been attempted in these cases. (read here)

Does The Patella Ever Luxate To The Outside?

Yes.

Although the vast majority of cases that veterinarians see involve luxation to the inside (medial side) of the knee, the kneecap of some dogs does occasionally luxates laterally (lateral patellar luxation). These lateral luxations tend to be more pronounced and debilitating than those that luxate medially. When lateral luxation occurs in small breeds, it tends to occur late in life.

In younger dogs, lateral luxation is more frequent in the large and giant breeds. When it does occur in these dogs, they usually have multiple misaligned bones in their rear legs from the hip on down. Some associate the problem with too little angulation in the hip, hock, and stifle joints.

The most common breeds to suffer that problem are Irish Wolfhounds, Great Danes and St. Bernards. Large dogs with this problem tend to suffer from a number of concurrent problems – all related to poor skeletal alignment. Because of this, many of these pets stand knock-kneed. Both knees are usually affected.

Giant breeds of dogs have increased mineral needs during their early rapid growth. They need good nutrition, an optimal dietary mineral balance (Calcium 1.1%, Phosphorus 0.9%). (read here) Moderating their growth rate is thought to minimize many forms of skeletal deformities they are prone to. (read here)

Some veterinarians believe that dogs whose patellas ride too high on their legs (patella alta) are at a higher risk of medial patellar luxation (MPL). (read here) Others believe that dogs that have patellas that ride too low (patella baja) are more likely to luxate laterally (to the outside). (read here)

How Will My Veterinarian Diagnose A Patellar Problem?

I mentioned before that In most cases, gentle thumb pressure from your veterinarian on the pet’s kneecap while the knee is extended is sufficient to cause patellar luxation in dogs that are prone to it. There is a distinctive pop or jerk as the patellar jumps out of its groove to the inner surface of the thigh where it can be readily felt in its abnormal position. The same extended leg manipulation allows your veterinarian to pop the patella back into place in dogs that arrive in a luxated, lock-knee state. Your veterinarian will probably want to take x-rays of both knees to determine if arthritic changes are already present. Deciding if your pet is in stage 2 or stage 3 is more difficult. Because it is a subjective decision, veterinarians you consult might disagree. Surgical specialists are more inclined to emphasize severity. So have more than one veterinarian examine your pet before deciding what, if anything, needs to be done. I suggest that you consult with the breeder as well.

Do All Dogs With This Problem Need Surgery?

No.

I do not believe that pets that limp only occasionally (grade 1) need surgery. Grade 2 pets are a harder decision, but they probably do not need surgery either. Just feed them a balanced diet, keep them trim (lean) and keep their toenails trimmed short. Give them a chondroitin/glucosamine supplements if you wish. In their older years, whirlpool, hydrotherapy and swimming might be helpful to lessen the effects of knee arthritis should it occur. If you do elect surgery for dour pet, there are minimally invasive arthroscopic techniques that you might consider. (read here)

Dogs carry the majority of their weight on their front legs. They do not seem to me to be inconvenienced even when running on three legs. However, patellar problems do not go away on their own – so you will have to judge how much of an inconvenience grade 2 patellar problems are to your pet.

Younger and middle-aged dogs showing pain, dogs showing the beginning changes of knee arthritis and those that fall in categories 3 and 4 do need surgery. Just be sure that radiographs (x-rays) and other tests are carefully evaluated to be sure that the lameness your dog is experiencing is directly attributable (caused by) a patellar problem and not to some other concurrent joint abnormality that your pet may also have.

What Type Of Surgery Does My Pet Need?

In contrasted to cruciate ligament or hip surgery, patellar surgery is less invasive, less expensive and generally has much better outcomes. When the surgery is performed before arthritic changes have begun in your dog’s knee, it is usually very successful in preventing future joint pain. Once arthritic changes have developed, surgery is considerably less likely to produce a pain-free leg.

What needs to be done depends on what structures in your pet’s knees are abnormal and how abnormal they are. No two cases are exactly alike. There are three surgical procedures that are commonly used to treat patellar luxation. Most cases can be cured with the first. If your veterinarian decides that ligamental reinforcement (lateral imbrication) will not be sufficient, he/she might add the second procedure, deepening of the trochlear groove. If that will probably not be sufficient, the surgeon may move the point where the patella’s ligament attaches to the tibia (tibial crest transposition).

In 2011, veterinary surgeons with a particular interest in luxating patellas published an article on their experiences correcting them. Their conclusion was that deepening the pet’s trochlear groove did not improve the surgical outcome. These pets were not followed for very long after surgery. It is quite common for a second study of this type to reach opposite conclusions from the first. But it is also common for widely accepted surgical techniques used on a dog’s knee, such as TPLO, to be later proven not to do what veterinarians thought they did. You can read their study here.

Reinforcement of the lateral collateral ligaments (lateral imbrication)

In mild cases, it is often sufficient to simply reinforce the weak lateral ligaments that keep the kneecap in alignment. When the inner or medial ligament has contracted or pulls too hard to the inner side of the knee, that ligament can be “stretched” (a medial desmotomy) at the same time to allow the patella to glide in its designated groove in a straighter course (not as likely to “jump the track”).

Deepening of the trochlear groove (= trochlear modification or recession, sulcoplasty)

Your pet’s patella rides in a channel on the face of the femur. Sometimes, this channel or groove is not deep enough in toy breeds to hold the patella in track (in course in the groove). This track is coated with a slippery cartilage that allows for smooth motion. In this surgery, this cartilage (hyaline cartilage) is carefully lifted off to one side while the notch is deepened, or a wedge of bone and cartilage are removed and then replaced in a deepened channel. You can read about the procedure as it has traditionally been done here. Question about its validity in green just above.

Relocation of the tibial attachment (=tibial crest transposition)

In some pets, the conformation (shape) of their knee structures is so out of line that reinforcement of their lateral ligament and deepening the trochlear groove will still not allow for smooth action of the knee. In these cases, the kneecap’s attachment to the tibia (shinbone) is thought to be too far to the inside of the leg. Sometimes, this has occurred bit by bit as a persistently luxated patella tugs on the attachment, slowly causing it to bend and grow inward – just like the steady pressure of braces realigns your teeth. At other times, the dog was just born with poor knee alignment. In both cases, the solution is to remove the point of attachment (tibial tuberosity) along with some underlying bone and reattach it farther lateral, so the patella moves more normally in a straight up-down line.

Some pets are born with tibias so distorted that the whole upper section of bone needs to be rotated on its shaft. These are procedures best left to a veterinary orthopedic specialist. It is not unusual for veterinarians attempting to repair these complex cases to discover other problems in the course of the surgery. That is when their specialized expertise is so important. You can read about some of these compound and difficult cases here and here. The earlier in your pet’s life that they are performed, the more positive the outcomes tend to be.

What Will Happen If I Don’t Have This Problem Fixed?

If your pet only suffers from a grade 1 condition, it should do fine without surgery. However, the higher the grade, the more likely your pet is to eventually develop arthritis in its knee leading to pain. Veterinarians cannot predict which pets with a grade 2 problem will develop painful knees later in life. That is the problem with delaying surgery in these grade 2 pets because arthritis, once it occurs, is irreversible. I am inclined to suggest lateral collateral ligament reinforcement to my clients when young-to-middle age pets in this situation are presented to me. That is because collateral ligament surgery in your dog is a relatively non-intrusive and safe procedure. It is often successful and does not preclude more extensive surgery later if it does not solve the problem. If the patella’s ligament attachment to the tibia was obviously out of alignment, I would move it to a more parallel position at the same time.

Should Both Knees Be Operated On Or One-At-A-Time?

I generally suggest that knees be operated on one at a time. This way the pet is never unable to get about. If both knees need surgery, the second one can be operated on eight weeks after the first. In pets that are still growing extensively, it is better to operate on both knees simultaneously because inactivity in one leg will cause bone and muscle in that leg to develop slower and differently than in the other.

Postoperative Care Required

Your pet will most likely leave the hospital bandaged and in need of exercise restraint until some healing has occurred. Take your dog out-of-doors only on a leash. Depending on its personality, your dog may need some tranquilization to keep it from initially overusing the repaired leg, and it may need a special collar to prevent it from chewing at its incision. Not all dogs chew at their incisions. But enough of them do and damage the work your veterinarian labored so hard to accomplish that most vets send all knee surgery home in an Elizabethan collar. Check it for a good fit from time to time. But please don’t take it off until your veterinarian tells you it is safe to do so.

Because it is so hard to maintain pets hygienically, many veterinarians give antibiotics to all their post-surgical cases. Because ligament reinforcement and attachment realignment (transposition) surgery is relatively straightforward, few post surgical complications occur. If only the knee ligaments were reinforced, the dog is usually back to its old self in three or four weeks. If more extensive procedures were performed, it might take six to eight weeks of limited exercise before it is using the leg normally.

Many vets suggest that beginning three weeks or so after surgery, physical therapy, swimming, hydrotherapy and range of motion exercises begin to help prevent muscle contraction and reluctance to use the leg.

Is It OK To Breed My Dog If It Has or Had This Problem?

I do not believe that that is a good idea.

We know that dogs that have this problem tend to pass it on to their puppies. Most dogs that develop luxating patellas appeared normal at birth and as puppies. But the genes they inherited from their dame and sire make it much more likely the problem will occur in them later. If you are a serious breeder or a conscientious occasional breeder, have your dogs certified free of the trait by the OFA (Orthopedic Foundation of America) or, at the very least, have your veterinarian thoroughly examine your adult dog(s) for a tendency to patellar luxation before considering breeding them. A technique that measures “Q-angle” might be helpful in choosing dogs least likely to pass on patella luxation tendencies. (read here) AKC papers and show medal history has nothing to do with health.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.