What Causes Those White Spots On My Cat’s Eyes?

Eye And Upper Respiratory Problems In Your Cat

Feline Herpes Virus-1, Chlamydia, Bartonella and Mycoplasma

Ron Hines DVM PhD

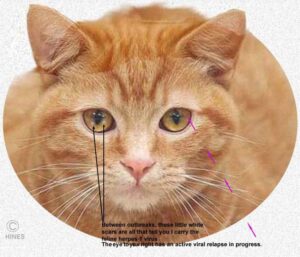

It is quite common for cats to have eye irritation and eye mattering that comes and goes. In between those relapses, nothing more might persist than pinpoint or rounded, milky-colored corneal scars – like the orange tabby cat on my top right drawing. Do you see the two (. .) on its right eye?

Another cat’s scratch, a dusty environment, allergies, dry eyes, tear duct blockages, internal eye problems or an unhealthy amount of weight loss associated with other diseases can all cause eye discharges or inflammation that looks somewhat similar. But more commonly, it is due to persistent infections with microscopic organisms that irritate the clear outer surface of your cat’s eyes (=its corneas = keratitis). The most common organism to causes that in cats is the Feline Herpes-1 virus (aka rhinotracheitis virus, aka cat flu). The second most common cause is probably infection with Chlamydophila felis (aka Chlamydia felis), perhaps then Mycoplasma or a combination of two or more of any of this group.

When these organisms infect your cat for the first time, they usually result in a generalized, upper respiratory infection, perhaps with fever, weepy eyes, a crusty nose and sneezing (see Respiratory Infections In Your Cat). These infections frequently clear up after a week or two with or without treatment. Most cats are never again bothered with the problem. But when your cat’s initial infection included the cat herpes-1 virus (a distant cousin of our human fever sore virus and of chicken pox) the virus never really leaves your cat’s body. A few viruses live on in a dormant, sleeping state in cells within your cat’s facial nerves and perhaps elsewhere. Veterinarians really do not know. Your cat will produce antibodies against the herpes virus. In most cases, your cat’s anti-herpes antibodies persist and keep these dormant virus sleeping. But stress and other factors that weaken your cat’s immune system can allow the virus to awaken from its latency.

So, a small percentage of cats that become infected with Herpes-1 virus relapse periodically. In most cats, these relapses are limited to some nasal drainage, sinusitis and/or sneezing. Other cats (probably the majority) simple begin shedding the virus again without any evidence of illness. However, even those cats are infectious to other cats. But in some cats, this virus proliferates in the clear, superficial layers of your cat’s eyes (its corneas). That causes periodic drainage, inflammation, and the formation of rounded milk white corneal scars-similar to the ones in the orange tabby at the top of this article. I am particularly partial to orange tabbies, you will see them in many of my articles. Some vets call this condition herpesvirus keratoconjunctivitis or infectious feline keratoconjunctivitis.

You might wonder why this virus has an affinity for your cat’s eyes. It probably has to do with the unique characteristics of the tissues that make up your cat’s cornea. To maintain transparency, your cat’s corneas normally have no blood vessels. Unlike other tissue, they receive their nutrients and antibodies only through the tears that bath them externally and from blood nutrients and antibodies that diffuse into them from deeper eye structures. To survive, corneal cells also rely on neurotropins supplied by the trigeminal nerves of the face that I already mentioned.

Between episodes, corneal scars range in size from pinpoint and barely noticeable, to over a centimeter in diameter. Although Herpes-1 of cats is in the same large herpes group of virus as our human herpes simplex virus, don’t worry. The herpes virus of cats cannot infect you (or your dog) nor can human herpes virus infect your pets. (read here) Even oysters have their own unique herpes issues. (read here)

Herpes virus flare-ups in cats are often associated with the stress of boarding, weather changes, other disease issues that weaken a cat’s immunity, new cats added to the household or new neighborhood cat rivalries. Adoption to a new home is a particularly stressful time for a cat. During these stress-related virus activation periods, portions of the outer layers of your cat’s cornea can lose their antibody protection. Secondary bacterial and mycoplasmal infection of those vulnerable areas can lead to deep ulcers of the cornea if they are not tended to by your veterinarian. Occasionally, they lead to sight-threatening penetrations into the cat’s eye. That is an important reason why active corneal ulcers need your veterinarian’s immediate attention.

Can Other Problems Be Confused With Viral Or Bacterial Eye Infections?

Yes

As I mentioned, there are non-infectious conditions that can mimic this disease. Those include allergic and eosinophilic eye disease, sensitivity to eye medications, environmental irritants and traumatic eye injuries. Cats are prone to rub their eyes when they itch for any reason. The result can be corneal tears and scrapes. Sharp claws occasionally injure the cornea during cat fights. Misplaced eyelashes (distichiasis) can also be a cause. (read here)

Diseases that increase your cat’s intraocular (eye) pressure (= glaucoma) and inflammation of the forward (anterior) chamber of your cat’s eye (uveitis) can also cause damage and scaring of the cornea. Due to their head conformation, Persian cats are more susceptible to dry eyes and other ocular problems that can also result in corneal ulcers. (read here)

What Treatments Are Available For My Cat?

Your veterinarian’s visual inspection of your cat’s eyes can’t result with 100% certainty in diagnosis of a corneal herpes-1 virus problem. But your veterinarian knows that there are very few other common explanations for the distinctive scars this virus leaves behind. So, your vet might add some other tests (such as a fluorescein dye examination, swab cultures and cytology) to help rule out other causes or cases that might have multiple causes.

PCR tests for feline herpes virus do exist. However, with so many cats shedding this virus, one can never be certain that herpes virus is the underlying cause of your cat’s eye issues – even when the test results are positive. When multiple pathogens are detected or suspected, your veterinarian might add antibiotics or antifungal agents to the treatment plan. Antibiotics and antifungal medications are effective against secondary invaders like mycoplasma, chlamydia and yeast, but not against virus. Most cats get better when their stress levels are reduced. When a viral relapse lingers, or when large portions of your cat’s cornea are involved, the most effective treatment is famciclovir (Famvir®). Read more about that medication here. Older, less expensive, topical products like idoxuridine eye drops (Herplex®) might also be effective – but you have to give them frequently throughout the day and side effects, if they occur, are unpredictable. (read here & here) If your work schedule or hesitancy prevents that, 0.5% custom-compounded cidofovir eye drops given twice a day have been said to be effective as well. (read here) Since herpes 1 viral episodes come and go on their own, it is difficult to decide when medications speeded the healing and when they did not.

For many years, the amino acid, lysine, administered orally twice a day, was thought to help cases of Herpes-1/rhinotracheitis in cats to resolve and, perhaps, to even decrease the frequency of relapses. This amino acid was thought to reduce the amount of another amino acid, arginine, that is present in the cat’s body (although experiments to document that had mixed results). Arginine is thought to be necessary for herpesvirus to reproduce. Most veterinary texts suggested a lysine dose of 250-500 mg per day. I gave this supplement until the acute flare-up had resolved, and I knew of many cat owners that continued the supplement indefinitely. However, more recent, better-designed studies have found lysine to be ineffective in treating herpes infections in cats or in people. (read here & here) Lysine can still be purchased at health food stores. If you or your veterinarian still choose to give it, pick a brand that is propylene glycol-free. Cats seem to dislike the taste of lysine when given alone. So, most owners mix it with a small amount of food.

Some cats appear to be uncomfortable or experience eye pain during relapses, but many do not appear to. It is difficult to determine when a cat is in pain. If your cat is squinting or the eye is noticeably inflamed, atropine eye drops can be helpful during recovery. Cats on that medication (it dilates their pupils) seem more comfortable in subdued light – just as you do after an eye exam.

Most cats experience periodic herpes-1 relapses with no permanent eye damage other than the small white scars left on their corneas that brought you to this page. But a few develop corneal flaps (tags) or non-healing areas that need to be surgically scraped and leveled to encourage proper healing. Some cats are left with long-term tearing that persists even after the cornea has healed. A very few cats, in which the eyelid experienced long-term inflammation, end up with hairs pointing toward the eye rather than away from it (entropion).

Eosinophilic Keratitis (aka keratitis – corneal inflammation)

Eosinophils are one of your cat’s immune system’s defensive cells. Eosinophilic keratitis (corneal damage) is one part of the many eosinophil-related diseases that affect cats. All result from your cat’s immune system making a mistake. (read here) When your cat’s eye(s) is involved, the eosinophils of your pet’s immune system increase in number within the several layers of the cornea – what should be the clear covering of the eye. When that happens, whitish raised plaques – one or more – become visible on the cornea of the affected eye(s). There is usually considerable mucus accumulation at the inner corner of the cat’s eye (its medial canthus) as well. Its 3rd eyelid is often more noticeable, extended and inflamed. Your veterinarian, or more likely a veterinary ophthalmologist, diagnoses eosinophilic keratitis by staining a gently scraped off preparation of cells from your cat’s cornea. If large numbers of eosinophils are seen when the slide preparation is stained and examined under a microscope, eosinophilic keratitis is your cat’s problem. As far as we know, herpes 1 and the other pathogens I mentioned play no part in this disease. At least, no links to them have been documented. Untreated, corneal issues can lead to blindness. Treatment of eosinophilic keratitis is frequently successful utilizing corticosteroid-containing eye drops, as well as medications that eliminate underlying secondary eye infections by mycoplasma and bacteria. When the problem persists in spite of those topical corticosteroid products, oral megesterol acetate (Megace®) is sometimes effective, as it has been in the other eosinophil-related diseases of cats. However, transient (or permanent) diabetes, weight gain, increased risk of mammary tumors, uterine infections in non-spayed females, and liver toxicity have been associated with megesterol. So, one must be relatively certain of the diagnosis. If topical or oral corticosteroids are given to a cat to resolve eosinophilic keratitis, but the problem is actually due to herpes-1 virus, corticosteroids can reactivate the virus. Eye irritation due to environmental contaminants and allergies also respond well to corticosteroid-containing eye drops – but the same cautions apply.

Dry Eyes =keratoconjunctivitis sicca

Eyes that lack sufficient tears can also be the underlying cause of superficial eye inflammation in cats. It can be diagnosed through a Schirmer tear test, a test that gauges the quantity of tears that are produced. As in humans, cats that do not produce enough tears are more subject to eye infections and corneal disease. (read here) Cats that are squinting should have their eye(s) stained with fluorescein dye as well. That test allows your veterinarian to see early corneal ulcers and any cuts, scrapes, or abrasions present, and gauge their depth. Deep ulcers sometimes need a temporary emergency corneal “patch”. (tarsorrhapy)

How Can I Lessen The Likelihood Of Some OF These Problems Occurring In My Cat?

Some of the cats that suffer from these recurring eye problems test positive for feline leukemia or feline immunodeficiency virus. So verify that your cat is both FLV and FIV negative. There is no cure for either of these virus diseases. If it is positive for either, your cat may be more subject to eye relapses, and it may take longer and require more medications to help it recover. When those two underlying problems have been ruled out, lowering stresses in your cat’s life is the best preventative within your control. Hard as it is for many cat lovers to accept, some of these cats will be happier and healthier in single-cat households. Diets rich in vitamin A might also decrease the frequency and severity of relapses – but remember that too much vitamin A is also undesirable. Moderate weekly lightly cooked portions of oily fish (mackerel, salmon, and tuna, in that order) are probably the best natural sources of vitamin A.

Effective vaccines against feline herpes-1 are available. But to be effective, these vaccines must be given before this common virus infects cats. That is quite a challenge because many kittens are already infected early in life by their virus-shedding mother – even before their eyes open. The stress of pregnancy, and nursing, often causes these herpes-carrying mothers to relapse (become viremic again) and pass the virus on to their kittens. The immaturity of the immune system of tiny kittens makes vaccines given at this early age unlikely to be effective. The vaccines used are part of the combination vaccines all veterinarians give to kittens at about 8-9 and 10–12 weeks of age. Many veterinarians give a third booster at ~14 weeks of age. The suggested timing differs slightly between manufacturers. Many cats from shelters are in the middle of a stress-induced relapse infection when I first see them. In those cats, the vaccines are also unlikely to be helpful. Yearly booster vaccinations against herpes-1/rhinotracheitis and other feline diseases are unnecessary and counterproductive. There is quite a bit of evidence that herpes-1/rhinotracheitis, calicivirus and panleukopenia vaccines do not need to be given frequently or throughout your cat’s life. (read here)

Bartonella

The bartonella organism can affect cats in many ways. It has been found that some cats with eye problems are positive for bartonella. Read about that here. However, just because your cat is PCR-positive for Bartonella does not mean that bartonella is the cause of its eye problem. That is because so many cats carry the bartonella organism (~6% in Illinois, 33% in Florida, 40% in Poland). (read here) Bartonella responded well to treatment with doxycycline, azithromycin or rifampin antibiotics. When giving your cat capsules or tablets, you should always follow the pill, capsule, or tablet with a considerable amount of water or meat broth. That is to keep capsules and pills from lodging in your cat’s throat (esophagus) and causing a stricture (=a scarred contraction causing swallowing difficulties).

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.