Correcting Spraddle or Splay Leg in Baby Birds

Ron Hines DVM PhD

What Is Spraddle Leg?

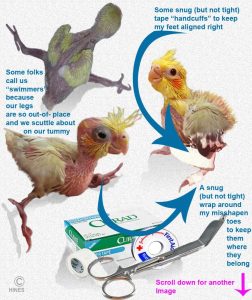

Spraddle-leg or splay-leg is a distorted leg problem that only affects birds that are still immature and growing. The problem occurs when abnormal lateral forces on a growing bird’s legs and feet causes the bones (femurs ,tibias , pelvis and toes)

The cause of this condition is usually a nesting area or nesting container, which is too slick for the young bird to grasp well. Not having enough shredded bedding or bedding of the wrong kind within a nest box also causes this condition. Another common cause is too rapid a growth rate in overfed, hand-reared birds. People occasionally bring me immature song birds with a single distorted leg. I assume that those cases result from the chick’s leg being tightly stuck in a crevice of the nest for a long period. A diet too low in calcium or vitamin D3 or too high in phosphorus could theoretically cause this problem or make it worse; but I have not personally seen spraddle-leg cases that I could attribute to that.

Baby birds that are in the process of developing spraddle-leg are much like novice ice skaters whose legs slide outward from the midline.

Can My Baby Bird Be Cured If It Develops Spraddle-Leg?

Correcting this problem in a rapidly growing baby bird is a fairly straightforward proposition. Reversing the forces that cause its legs to protrude sideways will slowly bring the legs back to the midline – if the bird has sufficient remaining growth time left. The same technique, performed more slowly and more cautiously will help birds of any age, but the results may not be as spectacular.

No two veterinarians or aviculturalists fix this problem in identical ways. Luckily all techniques are successful if they reverse the lateral forces that caused the problem in the first place. What is important is that no force be great enough to injure the bird’s delicate legs and joints and that no device or apparatus restrict circulation, bone or muscle growth. It requires daily or even more frequent inspection and possible adjustments. Bone and cartilage are dynamic tissues that continuously reform and re-contour in response to stress forces they encounter. In correcting spraddle-leg, you are simply redirecting those forces. You never want to rush the process, tear or deform existing joints or expect bone architecture to change rapidly.

I do not like methods that truss up the bird or limit normal forward and backward motion of the legs with foam or braces because they do not allow for normal bone and ligamental development while the bird heals. This is particularly true during the phenomenally fast growth spurt of newly-hatched birds. Preventing normal motion of a joint during that period is sufficient to “freeze” that joint up through ligament and muscle shortening (contraction) – within less than a week.

To protect the baby’s legs, I wrap a 1/8 to 1-inch wide strip of two-sided foam sticky tape, that is normally used to attach picture-hanging hooks around either foreleg (tibias). I leave a wide gap in the tape on the medial (inner) surface of the leg so that circulation to the foot is maintained. Then I fashion and apply a shackle (hobble or handcuff) make out of a 1/8 to 1 inch strip of Curity™ type white bandage tape so that the legs can no longer splay outwards. This apparatus is positioned just proximal (above) the “ankle” (tibiotarsus). Ouchless tape and bandages fall off too easily. When the time finally comes to remove the shackle or when it needs to be changed, olive oil an a pledget of cotton will remove remaining tags of the gluey adhesive.

I reapply the tape daily so that the inward tension on the legs is always very mild. Each day the legs are positioned closer to the midline. If X represents the bird’s body and o represents the bird’s legs, first the legs will look like o——-X——-o Then gradually over a few days; I move them more toward the midline: o—–X—–o Then to: o—X—o Then, finally, to oXo. The entire procedure should take 7-30 days in immature birds. It can take much longer in birds that are no longer actively growing. During that period attempts should be made to massage the feet and allow the bird to perch so that its toes and feet do not become atrophied, contracted or distorted. As soon as possible I get them on large-diameter perches because feet and toes are also usually abnormally shaped due to the spraddle. One has to be sure circulation, temperature, color and consistency of the feet always remain normal – if not, the bands are too tight or one is putting too much inward torque on the legs too quickly. It has always amazed me how quickly the bones of the leg and pelvis remodel and correct the problem. If splay-leg is advanced, angulation at the “ankle” (tarsus) accompanies bowing of the upper legs. This ankle angulation is harder to correct but does not incapacitate the bird. The younger a bird is when you begin, the more likely the ankle problem will self-corrects when the upper legs and hips are straightened.

As I mentioned, the older the bird, the harder spraddle–leg is to correct. This is because bones of older nestlings and adults are more calcified and rigid and cell structure less adaptable to change. Correcting the problem in grown or nearly grown birds sometimes requires that a veterinarian cut and wire abnormally shaped bones in a procedure somewhat similar to the “ triple pelvic osteotomy ” performed on humans and dogs. In these birds, the legs will probably never return to their completely normal anatomy or function. It is likely to require human assistance for the rest of its life.

Mature parrots with marked uncorrected spraddle-leg do quite well when given additional perches and climbing ladders. They will need their toenails trimmed more frequently and they will often develop skin ulcers at pressure points on their body. None are life threatening. They need a soft substrate cage bottom. As for wild bird species, I question the humaneness or kindness of keeping walking and perching birds that can not adequately walk or perch the way God intended them to. It can be done, but I try to talk my clients out of doing so.

Does Every Case Of Spraddle-leg Need Treatment?

Birds rapidly adapt to their disabilities when they are young. But all birds with spraddle-leg need to be tended to as soon as the problem is noticed. That goes for minor deviations as well as major ones. Bone remodeling continues throughout life and with time, abnormal angle forces working with gravity – even small ones – lead to joint deterioration. So arthritis, joint swelling and inflammation will occur in untreated birds with this problem at a much younger age.

Can I Do The Taping Myself Or Do I Need A Veterinarian To Do It?

It takes a person with a gentle touch who is experienced raising baby birds of the same species as yours, to handle routine spraddle-leg cases. That person might be a veterinarian. it might be an aviculturalist, an experienced wildlife rehabilitator, a veterinary technician or a human nurse. The angel of success lands on the shoulder of those with talent, experience and dedication – seldom someone with college credentials, but someone with a gentle touch and plenty of avian experience. However, once a bird’s skeletal growth has slowed or stopped, it generally does take a veterinarian with considerable bird experience to perform complex procedures. In those cases, birds may need anesthetics:

Bones may need to be cut and re-positioned to gain any semblance of a normal leg and grasp. You can read about some of the techniques I use here

This morning a lady arrived with an immature bird that she thought needed leg surgery because it could not walk. It was grebe, what we down her on the Border a Hell Diver. I explained to her that that is how God intended them to look. So I took down the blender. Went to the freezer for some some mullet, bluegills and night crawlers and made the bird a malt.