Addison’s Disease in Your Dog Treating Hypoadrenocorticism

Ron Hines DVM PhD

What Is Addison’s Disease (Hypoadrenocorticism)?

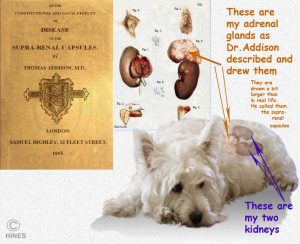

I am going to tell you some things about hypoadrenocorticism – a long word for a comparatively simple, but very serious, disease that Dr. Addison recognized well over a hundred years ago. We still call it Addison’s because it is a much easier word to say than its scientific name. Both you and your pet have a Lima bean-shaped gland just above/ahead of each kidney – the adrenal glands. Although they are quite small, they have two very critical functions. Their outer layer, the cortex, produces cortisol (a glucocorticoid) hormone which we all must have to deal with stress. It also produces a second hormone, aldosterone (a mineralcorticoid), which one must have to regulate the amount of salt in our bodies. Cortisol also decreases inflammation, increases blood sugar, suppress the immune system, increase the production of fat and decrease the number of certain white blood cells called lymphocytes that are involved in immunity.

The adrenals produce more cortisol in stressful situations (both physical and mental stress) than when your dog is calm. The aldosterone, or salt-regulating hormone that the outer adrenal gland layer also produces regulates the amount of sodium (Na) and potassium (K) in your pet’s blood. Both Na and K need to be kept within tight limits in order for your pet’s body to function correctly. The inner layer of the adrenal gland is called its medulla. It plays little part in Addison’s disease. The medulla (medullary portion) produces the epinephrine which we and our pets also use to deal with sudden stress.

Is Addison’s Disease A Common Problem In Dogs?

Addison’s disease is not a common disease in dogs. Its mirror image, Cushing’s disease, is much more common in dogs. But veterinarians think and talk about Addison’s a lot. That is because pets with Addison’s come through our clinic doors “pretending” to have so many other health issues. Often it takes repeated office visits, frustrated clients and perplexed veterinarians, before the light bulb comes on in our heads and the word, Addison’s, flashes through our minds. Once that happens, the diagnosis and treatment of your pet are usually quite straightforward. Addison’s disease occurs in both sexes. It appears to be a bit more common in female dogs. Dogs that develop the problem are usually over 5.5 years of age when major signs are first noticed. But because the destructive processes that lead to Addison’s disease occur slowly, these pets were in the process of loosing their adrenal gland function considerably earlier than that. Occasionally, an elderly dog will develop Addison’s disease as part of a malignancy/cancer situation. (read here)

Are Certain Dogs More Susceptible Than Others?

Yes.

Some breeds do develop Addison’s disease more frequently than others. Genetic predisposition occurs when a breed or a line of dogs relies on too few ancestor founding animals. That is, all dogs in the breed or line are too closely related (inbred). These high-incidence breeds include Portuguese water dogs (read here), duck-trolling retrievers, standard poodles (read here), wheaten terriers, Great Danes, and the westies. But any dog has the potential to develop Addison’s disease.

Is There More Than One Form Of Addison’s Disease?

Yes.

Veterinarians recognize three forms of Addison’s disease:

The Typical (Primary Adrenal Form):

In the majority of pets that develop Addison’s disease, their problem is destruction or loss of the cells that produce cortisol and aldosterone in their adrenal gland cortex (AZF cells in the zona fasciculata). In these pets, their immune system has mistakenly identified these cells as foreign to the pet’s body – seen as something that shouldn’t be there that needs to be destroyed. This is what occurs in all autoimmune diseases. In dogs, some veterinarians believe that over-vaccination might be one of the causes of autoimmune disease. (read here)

The Secondary (Pituitary Form):

Less frequently, a messenger hormone, ACTH, that is normally produced in your pet’s pituitary gland ceases to flow adequately. Without ACTH, the cells in the dog’s adrenal cortex that normally produce cortisol and aldosterone do not do so. This less-common type of Addison’s disease is called secondary or pituitary-based or Addison’s disease. I see Addison’s disease more than I should in dogs that have received multiple injections of long-acting steroid hormones (methylprednisolone acetate= ”Depo” ) as a “quick fix” for itchy skin. NEVER allow that form of treatment for your dog’s allergic skin problems (atopy) and think twice before attempting to relieve moderate itchy allergies with Atopica® as well. When due to overzealous corticosteroid administration and then discontinuing those drugs – particularly abruptly – it would be called iatrogenic Addison’s disease.

The Atypical Form:

Your pet’s outer adrenal gland layers, its adrenal cortex, is itself divided into three layers, the outermost zona glomerulosa, the central zona fasciculata and the innermost zona reticularis. Usually, but not always, all three layers become dysfunctional together. However, the outermost layer, in the zona glomerulosa, is sometimes initially spared. It is the one most responsible for making aldosterone – the hormone that controls the body’s salt concentrations (sodium and potassium). This portion of the zona glomerulosa will occasionally continues to function while the other two cortisol-secreting layers fail. This is sometimes called Atypical Addison’s disease. In these atypical cases, the pet only needs to be given cortisol-like drugs (prednisolone, prednisone, etc.) to keep it stable. It is also common for dogs with the pituitary form of Addison’s to also continue to make sufficient aldosterone (a mineralcorticoid). Those dogs too can be maintained on a corticosteroid alone. The severe “crashes” vets see in Addison’s dogs are usually in the ones that have the most serious problems in the outermost layer. They are the ones that develop electrolyte imbalances that send them to emergency animal hospitals. When a pet has had an abnormal ACTH stimulation test, there is a very good chance that eventually, all three layers of the adrenal cortex will fail – even if the pet’s blood electrolytes come back normal or close to normal for now. “Atypical” can mean different things to different veterinarians. So, the term “atypical” can be used to describe conditions that are not quite alike.

What Are The Symptoms of Addison’s Disease?

Addison’s disease (hypoadrenocorticism) is a chronic disease. That means it develops gradually, with ever-increasing signs. So the first symptoms your dog experiences will probably be written off to something else: Too much exercise or excitement, indigestion, a mild “bug” the pooch caught at the doggy park, etc., etc. Those early signs often include listlessness, weakness, vomiting, diarrhea or loss of appetite that come and go. Because early Addison’s symptoms are mild and come and go naturally, vets often treat these cases symptomatically with anti-vomit medications (anti-emetics) anti-diarrheal medications, bland diets and perhaps an antibiotic like metronidazole (Flagyl®). The dogs get better, so the complicated diagnostic tests don’t get run. But with time and repeat incidents, veterinarians and owners often put two and two together. They realize that these health crises are occurring shortly after stress – a big party, guests in the home, rowdy kids, a period at the boarding kennel, stress in the household etc. Because Addison’s disease is usually progressive, the time often eventually comes when the dog becomes quite ill. At that point (often at some nighttime emergency clinic) blood electrolytes do get measured and, if the veterinarian is astute, the possibility of Addison’s disease comes up. Those dogs are in what we call an “Addsonian crisis”. This is a form of shock and collapse of the circulatory system that can be fatal. Some pets do not present with these classical signs. They might be brought in with very low blood sugar levels (hypoglycemia) or seizures or muscle tremors or heart beat irregularities. So, they might be misdiagnosed as having reoccurring pancreatitis, kidney or heart disease. The most telling thing I have seen in these masquerading cases – the thing that should alert owners and veterinarians alike – is a pet that enters the emergency clinic one night looking like he or she is on death’s doorstep and leaves the next day looking fit as a fiddle with a muddled diagnosis. Occasional cases of Addison’s disease present as an inability to fully swallow or a pet that repeatedly regurgitates (vomits) undigested food (megaesophagus).

Can Addison’s Disease Be A Life-threatening Emergency?

Yes.

A circulatory collapse (Addisonian crisis) can be fatal if the changes in blood electrolyte levels (sodium too low, potassium too high) are not quickly corrected. This requires substantial amounts of intravenous fluids, supportive care and close monitoring. If the pet’s blood sugar levels have dropped abnormally low, they need to be elevated. If diarrhea and vomiting have dehydrated the animal, that needs to be quickly corrected as well. Rapidly acting corticosteroid medications such as intravenous prednisolone sodium succinate or dexamethasone sodium phosphate often improve the situation too.

Are There Other Health Problems That Could Be Confused With Addison’s Disease?

Yes.

After reading this far, you already understand that many health issues can be easily confused with Addison’s disease – particularly in its early stages. Some Addison’s case are at first confused with acute pancreatitis. (read here) Others get confused with hypoglycemia, food poisoning, parvovirus enteritis, gastric volvulus or twist, intestinal intussusceptions. Tests that diagnose Addison’s disease with certainty are time-consuming and expensive. So, they are often put off until treatment for other possible causes of sudden weakness and intestinal problems fail.

It is very common for dogs, showing early non-specific symptoms to be given intravenous fluids, like lactated ringers solution (LRS), along with corticosteroid injections. Just by coincidence, that happens to be quite similar to the specific treatments for an Addisonian crisis. So, the pet gets better without the veterinarian or owner really knowing why. For reasons we do not understand, it appears to some that whipworms can affect a dog’s sodium and potassium levels much like Addison’s disease does. If you suspect Addison’s disease but its ACTH test was normal, giving your pet wormer that also controls whipworms might be prudent. A course of Panacur® (fenbendazole) or switching to a moxidectin-based heartworm preventative such as Advantage Multi® should eliminate them. In Europe and the UK, Dolpac® (oxantel) is also effective. A whipworm infection can be hard for your veterinarian to diagnose since the parasite’s eggs can be rare in the dog’s feces.

What Tests Will My Vet Run To Diagnose The Problem?

Abnormally high blood potassium level and abnormally low blood sodium levels can alert veterinarians to the possibility of Addison’s disease, but they are not enough to diagnose it. The levels of both can be normal in your pet’s blood samples when it is between major crises. Low urine specific gravity (urinalysis specific gravity too dilute (read here) high levels of metabolic waste in the blood (elevated BUN and/or creatinine) and increased body acidity (metabolic acidosis) are also common in Addison’s disease; but they also occur in many health problems not related to your pet’s adrenal glands. You can see what the normals are for all these values in your dog here.

ACTH Stimulation Test

The most accurate way veterinarians have to diagnose Addison’s disease is performing an ACTH stimulation test on your dog. In this test, a blood sample is taken from your pet and the level of cortisol in it is measured. After that, a small amount of cosyntropin (Cortrosyn™ or Synacthen® ), products similar to your dog’s pituitary hormone ACTH, is injected into your pet. After a period of time, another blood sample is taken from the pet. When the adrenal glands are working normally, that injection will cause your pet’s blood cortisol levels to rise significantly. When it does not, it is evidence that the pet’s adrenal glands do not have the reserve capacity they need to produce additional cortisol. This is the definitive test for primary Addison’s disease. When pre-test cortisol levels are consistently low, and post test levels rise dramatically, secondary Addison’s disease needs to be considered. Those rarer pets still have functional adrenal glands, the glands are just not receiving enough ACTH messenger chemical from the pituitary gland to stimulate their adrenal gland cortisol production.

Low Dose ACTH Stimulation Test

In the USA, Cortrosyn® has become quite expensive. So, veterinarians have adapted the test to work with smaller amounts of the drug. You can read about that here. Veterinarians in Zurich and Purdue universities reported that a single blood assay of the pet’s Cortisol-to-ACTH Ratio was also an effective and less expensive preliminary screening test for Addison’s disease. (read here & here) I know of no US laboratories offering the test.

Ideas That Went Nowhere

There was some thought that a doppler ultrasound examination of your pet might detect abnormal adrenal glands. An article on that was published in 1997. (read here) Another study found that dogs with Addison’s disease tended to have high-end lymphocyte counts along with abnormally low sodium:potassium ratios (less than 27). (read here) The WBC and blood chemistry tests that give those values may have already been performed on your dog. Another group at the veterinary school in Davis CA attempted to locate genetic markers that might indicate that a dog was prone to developing Addison’s disease.

Are There Simple Things I Can Do At Home To Monitor My Dog’s Treatment?

Yes.

Besides returning to normal blood sodium and potassium concentrations, dogs with Addison’s disease that is well controlled should return to producing normal urine volume. Not all dogs with uncontrolled Addison’s disease drink and pee excessively – but many do. They do so because they lack cortisol and, in many cases, aldosterone hormone as well. (read here). So dogs that have their Addison’s disease well controlled with medications should produce more concentrated urine. It is quite simple for you to measure your dog’s urine concentration at home. Many of my clients, dealing with other health conditions such as bladder and kidney stones do. To see how the test is done, go here:

What Medications Will My Pet Be Needing?

Most dogs with Addison’s disease will need to be medicated for the rest of their life. Most will require two forms of medication, one to keep their blood potassium and sodium levels (blood electrolytes) optimal and another to replace the cortisol that they can no longer produce. The body’s cortisol needs change, depending on stress, exertion, exercise and the pet’s changing environment. So one dose will not fit all situations your pet will encounter over the years it lives with Addison’s disease.

If your dog has typical Addison’s disease, where both aldosterone and cortisol are deficient, most veterinarians will stabilize your pet with monthly injections of desoxycorticosterone pixelate (DOCP). It is sold under the trade name, Percorten-V®. Percorten replaces the mineralcorticoid hormone, aldosterone, that dogs with typical Addison’s disease no longer produce in sufficient amounts.

Dogs with typical Addison’s disease also need as synthetic corticosteroid to replace the cortisol they no longer produce in sufficient quantities. Oral prednisone or prednisolone is the most common cortisol-substitute that veterinarians dispense for that. There is a human oral medication, fludrocortisone acetate (Florinef®), that replaces both the aldosterone and the cortisol with a single drug. However, it is quite expensive. So it is not as widely used by veterinarians as the Percorten/prednisolone combination therapy. Fludrocortisone has now off-patent and is available in less expensive, generic form. Therefore, perhaps it will become the treatment of choice.

Dogs with secondary or atypical Addison’s disease may still produce sufficient aldosterone. If that is the case they only need a cortisol-substitute, like prednisolone, to maintain their health. Cortisol is a compound that the pet’s adrenal glands meter into its bloodstream in ever-changing amounts designed to meet its current metabolic needs. So the dose of corticosteroid replacement you give your pet needs to also vary according to the dog’s anticipated metabolic needs. It will need more when you anticipate strenuous exercise, boarding, grooming, or any situation that puts excess demands on its body. It will need less when its body is unstressed and at rest.

All pets with Addison’s disease need periodic monitoring of their blood potassium and sodium levels. Once you know how your pet is reacting to its medications, those tests can be done less frequently. Over time, expect the required dose of each medication to change. Many pet owners have heard that corticosteroid medications, like prednisolone, should not be given every day because they cause adrenal gland suppression (cause the adrenal glands to “get lazy”). That is true in dogs with healthy adrenal glands. But dogs that cannot make sufficient natural cortisol need their replacement medication every day. Don’t stop just because your dog appears happy for a few days without it. If your pet begins to drink and urinate excessively (in the absence of kidney disease or diuretic medications); if it gains considerable weight; if it is subject to repeat infections; or if its blood sugar, liver function or kidney function tests (BUN, creatinine) results increase, its cortisol replacement dose might need to be lowered.

How Long Can My Dog Live With Addison’s Disease?

The problems that Addison’s disease causes in sodium and potassium levels and a lack of cortisol are straightforward and quite correctable with medications. So your pet has the potential to live a very long life. How long a life depends entirely on how well Addison’s disease is managed. Your dog will depend on you to protect it from stress and to tailor its medication dose and frequency to its daily needs. That is not something your veterinarian can do for you on a day-to-day basis. Every dog will be different. But after a period of time on its medications, and after enough blood tests have been run to see how these medications are affecting it, you will be able to make the fine adjustments your pet will need to return to its favorite activities and enjoyments. Concentrate on providing your pet with as low stress a lifestyle as possible, plenty of love, good nutrition, adequate exercise, weight control, and attention to the other health issues that life invariably brings our way.

You are on the Vetspace animal health website

Visiting the products that you see displayed on this website help pay the cost of keeping these articles on the Internet.